[Image: Valets stretch at the National Valet Olympics in Palm Springs; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Valets stretch at the National Valet Olympics in Palm Springs; photo by BLDGBLOG].

When I first heard about the National Valet Olympics, I knew it was something I’d want to see someday. The nation’s best valet parkers gathering together in a parking lot somewhere—in Chicago, in Miami Beach, in Palm Springs—to wage spatial warfare against one another, battling head-to-head over who has the best parking technique? It sounded like something J.G. Ballard would come up with while playing Settlers of Catan.

[Image: Getting ready for the National Valet Olympics; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Getting ready for the National Valet Olympics; photo by BLDGBLOG].

The very idea that there could be an organized event for competitive valet parking was fascinating to me, an unexpected variation on a peculiarly American narrative of the upstart athlete, the self-taught Natural.

The games evoked images of men and women in small towns throughout the United States dragging themselves out of bed before dawn to practice three-point turns and parallel parking in under-lit lots, of kids growing up trading sports cards featuring portraits of valet parkers, of autographed posters hanging on the walls of rental car facilities drawing consumers’ attention to these legends of American emptiness.

Who among us can master the modern lot, its open geometry, its clean lines, its spatial potential? Why be LeBron James when you can be the world’s best valet parker?

[Image: Advanced Parking Concepts valets stretch their legs at the National Valet Olympics; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Advanced Parking Concepts valets stretch their legs at the National Valet Olympics; photo by BLDGBLOG].

The Olympics were as much as about a niche athletic pursuit as they were about everyday transportation infrastructure, I thought, and I had my calendar marked for more than a year leading up to the 2017 games.

[Image: Packing trunks at the National Valet Olympics in Palm Springs; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Packing trunks at the National Valet Olympics in Palm Springs; photo by BLDGBLOG].

I was finally able to attend the Olympics in person for The Atlantic, and the resulting article just went up online.

Held in Palm Springs, the games introduced me to a valet who grew up in a Syrian refugee camp, as well as one who volunteers with the California Army National Guard; I heard the story of a regional manager who once SCUBA-dived through a flooded parking lot outside New York in order to check on clients’ cars, and I followed one team in particular, Advanced Parking Concepts (APC) from Verona, New Jersey, on their most recent attempt to win it all. Taking the games seriously, APC got into combat shape by running wind sprints up the same New Jersey hill where Herschel Walker once trained.

[Image: The stage is set at the National Valet Olympics in Palm Springs; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The stage is set at the National Valet Olympics in Palm Springs; photo by BLDGBLOG].

If this sounds even remotely interesting—transportation infrastructure as a venue for personal athletic achievement—then consider reading the article in full over at The Atlantic, and, if you’re a valet parker, please be in touch! I heard so many good stories while writing this article, and I’d love to hear more.

[Image: APC valets huddle during the National Valet Olympics; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: APC valets huddle during the National Valet Olympics; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Test-crash from “

[Image: Test-crash from “ [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Michael Heizer’s rock; Instagram by

[Image: Michael Heizer’s rock; Instagram by  The Space Shuttle in front of a doughnut shop; photo by Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer

The Space Shuttle in front of a doughnut shop; photo by Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer  [Image: The Space Shuttle Endeavour in Los Angeles; photo by

[Image: The Space Shuttle Endeavour in Los Angeles; photo by  [Image: A shrink-wrapped section of a nuclear submarine; photo by Lindsey Dickings via the

[Image: A shrink-wrapped section of a nuclear submarine; photo by Lindsey Dickings via the  [Image: Photo by Lindsey Dickings via the

[Image: Photo by Lindsey Dickings via the  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

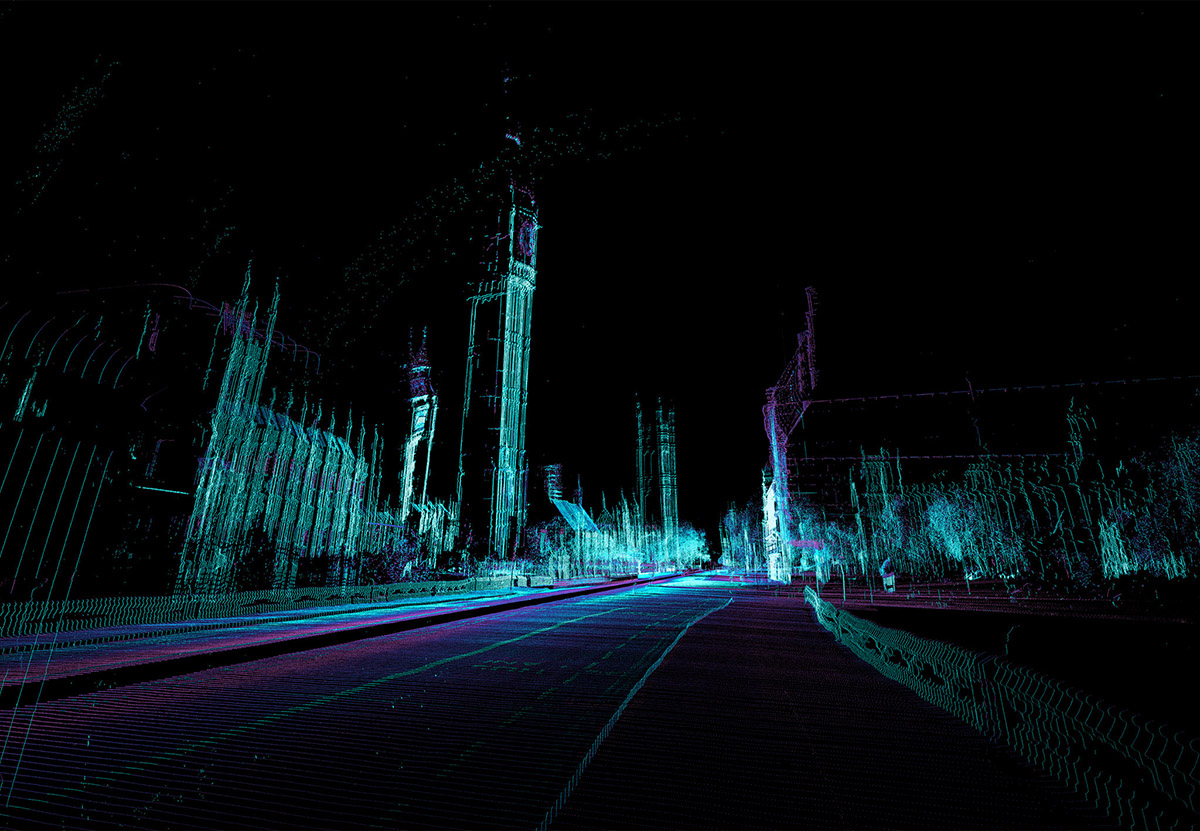

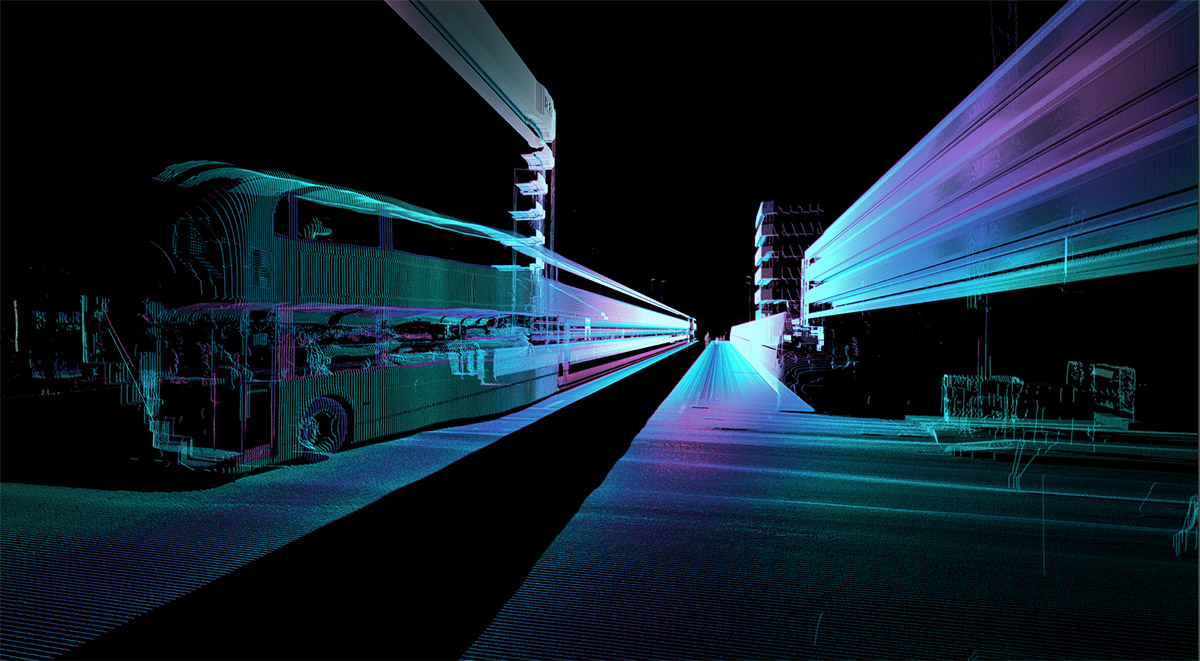

[Image by

[Image by  [Image by

[Image by

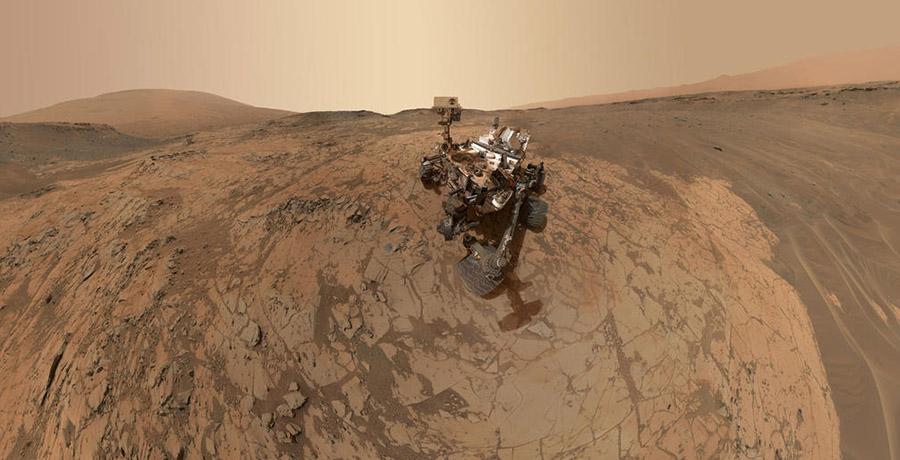

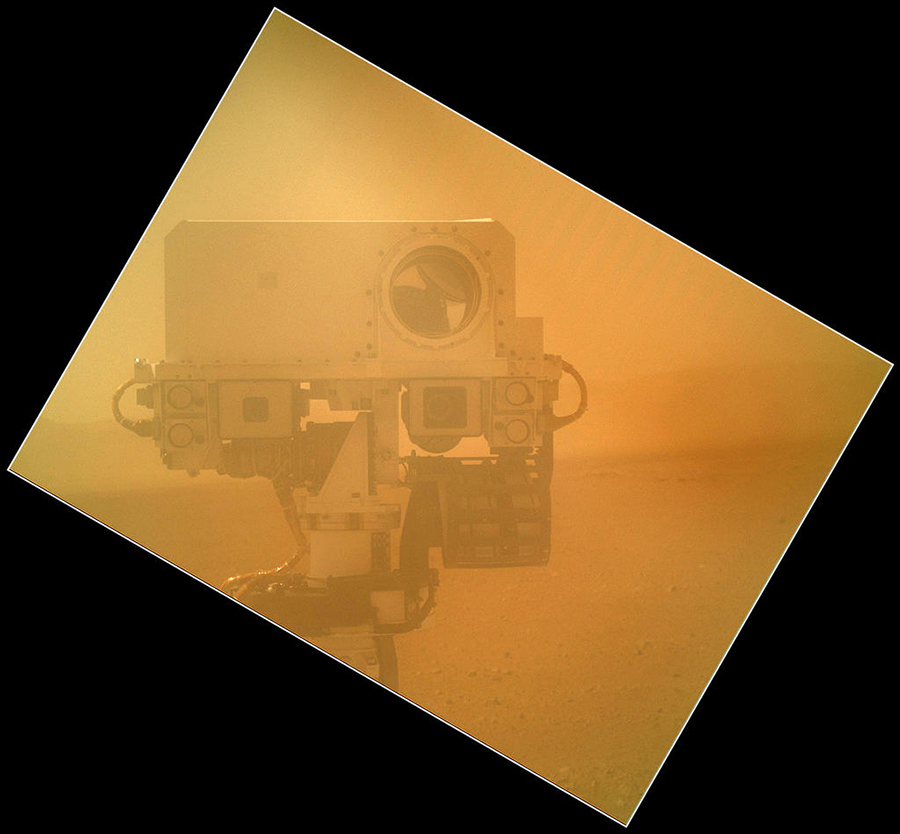

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via  [Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via

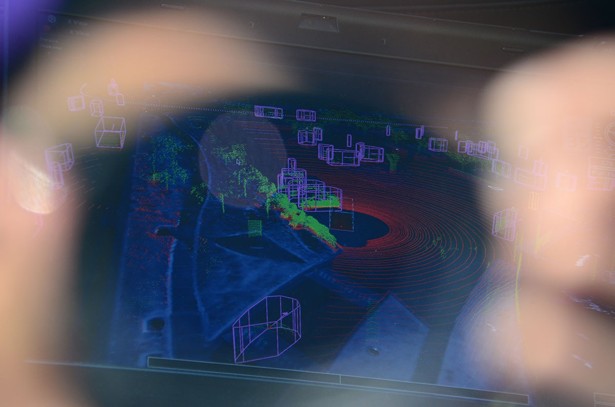

[Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via  [Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by

[Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from  [Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via

[Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via