[Image: Illustration by Benjamin Marra for the New York Times Magazine].

[Image: Illustration by Benjamin Marra for the New York Times Magazine].

As part of a package of shorter articles in the New York Times Magazine exploring the future implications of self-driving vehicles—how they will affect urban design, popular culture, and even illegal drug activity—writer Malia Wollan focuses on “the end of roadkill.”

Her premise is fascinating. Wollan suggests that the precision driving enabled by self-driving vehicle technology could put an end to vehicular wildlife fatalities. Bears, deer, raccoons, panthers, squirrels—even stray pets—might all remain safe from our weapons-on-wheels. In the process, self-driving cars would become an unexpected ally for wildlife preservation efforts, with animal life potentially experiencing dramatic rebounds along rural and suburban roads. This will be both good and bad. One possible outcome sounds like a tragicomic Coen Brothers film about apocalyptic animal warfare in the American suburbs:

Every year in the United States, there are an estimated 1.5 million deer-vehicle crashes. If self-driving cars manage to give deer safe passage, the fast-reproducing species would quickly grow beyond the ability of the vegetation to sustain them. “You’d get a lot of starvation and mass die-offs,” says Daniel J. Smith, a conservation biologist at the University of Central Florida who has been studying road ecology for nearly three decades… “There will be deer in people’s yards, and there will be snipers in towns killing them,” [wildlife researcher Patricia Cramer] says.

While these are already interesting points, Wollan explains that, for this to come to pass, we will need to do something very strange. We will need to teach self-driving cars how to recognize nature.

“Just how deferential [autonomous vehicles] are toward wildlife will depend on human choices and ingenuity. For now,” she adds, “the heterogeneity and unpredictability of nature tends to confound the algorithms. In Australia, hopping kangaroos jumbled a self-driving Volvo’s ability to measure distance. In Boston, autonomous-vehicle sensors identified a flock of sea gulls as a single form rather than a collection of individual birds. Still, even the tiniest creatures could benefit. ‘The car could know: “O.K., this is a hot spot for frogs. It’s spring. It’s been raining. All the frogs will be moving across the road to find a mate,”’ Smith says. The vehicles could reroute to avoid flattening amphibians on that critical day.”

One might imagine that, seen through the metaphoric eyes of a car’s LiDAR array, all those hopping kangaroos appeared to be a single super-body, a unified, moving wave of flesh that would have appeared monstrous, lumpy, even grotesque. Machine horror.

What interests me here is that, in Wollan’s formulation, “nature” is that which remains heterogeneous and unpredictable—that which remains resistant to traditional representation and modeling—yet this is exactly what self-driving car algorithms will have to contend with, and what they will need to recognize and correct for, if we want them to avoid colliding with a nonhuman species.

In particular, I love Wollan’s use of the word “deferential.” The idea of cars acting with deference to the natural world, or to nonhuman species in general, opens up a whole other philosophical conversation. For example, what is the difference between deference and reverence, and how we might teach our fellow human beings, let alone our machines, to defer to, even to revere, the natural world? Put another way, what does it mean for a machine to “encounter” the wild?

Briefly, Wollan’s piece reminded me of Robert MacFarlane’s excellent book The Wild Places for a number of reasons. Recall that book’s central premise: the idea that wilderness is always closer than it appears. Roadside weeds, overgrown lots, urban hikes, peripheral species, the ground beneath your feet, even the walls of the house around you: these all constitute “wilderness” at a variety of scales, if only we could learn to recognize them as such. Will self-driving cars spot “nature” or “wilderness” in sites where humans aren’t conceptually prepared to see it?

The challenge of teaching a car how to recognize nature thus takes on massive and thrilling complexity here, all wrapped up in the apparently simple goal of ending roadkill. It’s about where machines end and animals begin—or perhaps how technology might begin before the end of wilderness.

In any case, Wollan’s short piece is worth reading in full—and don’t miss a much earlier feature she wrote on the subject of roadkill for the New York Times back in 2010.

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

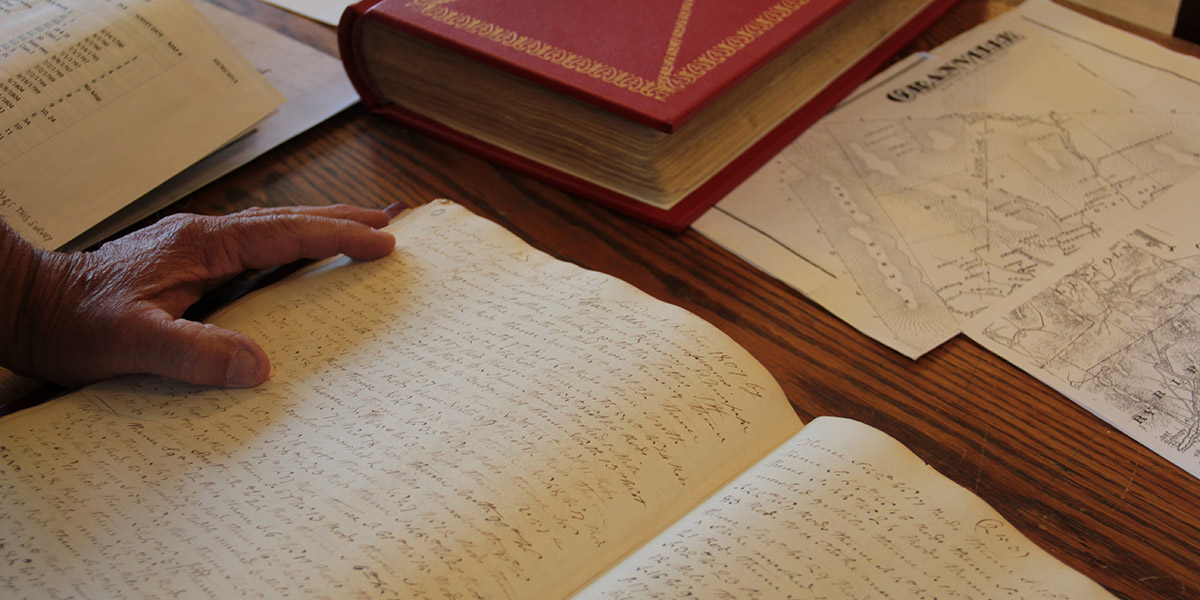

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

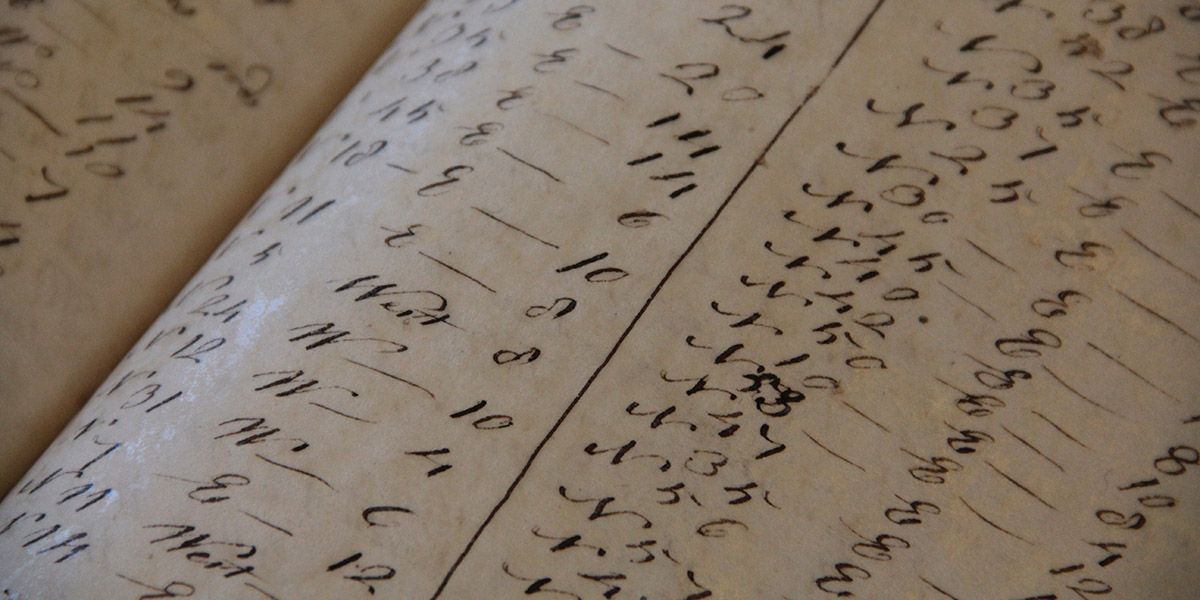

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

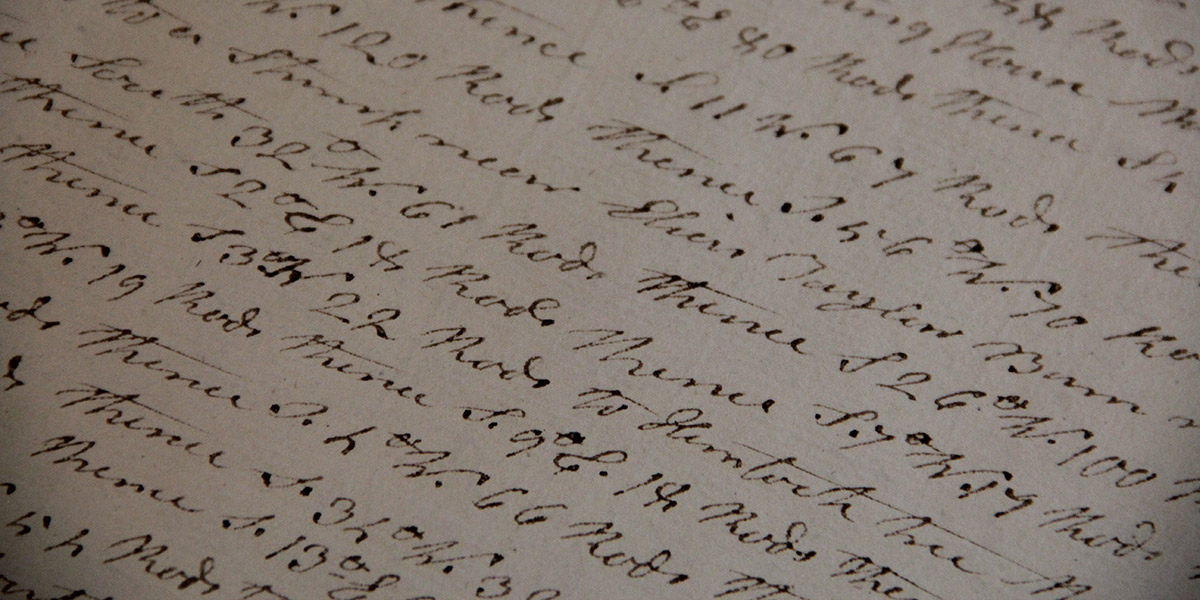

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

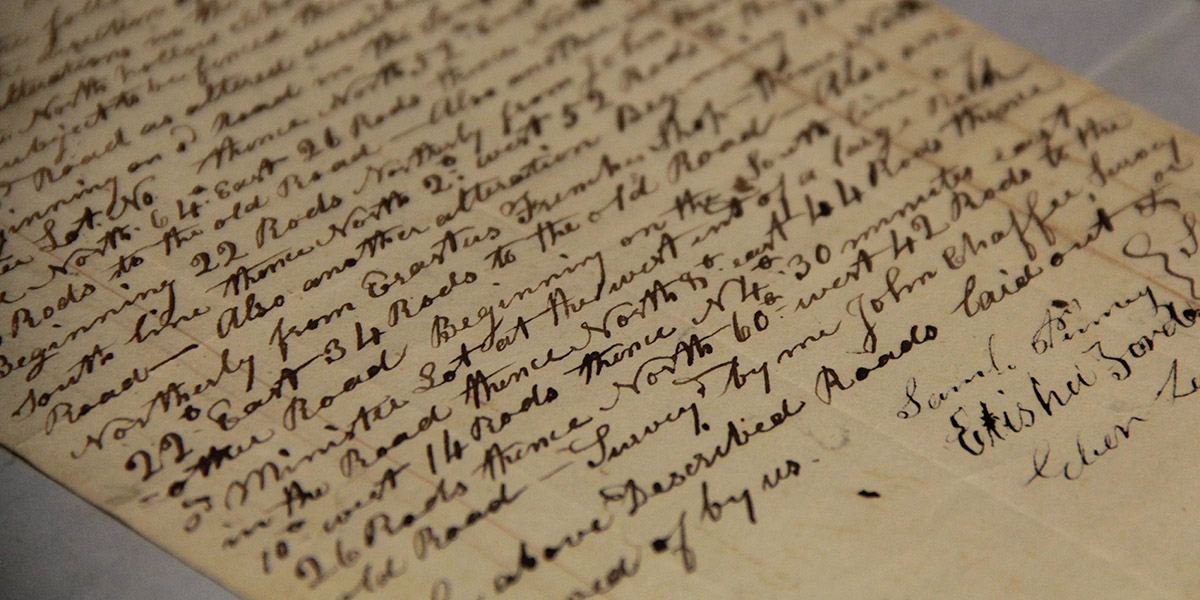

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

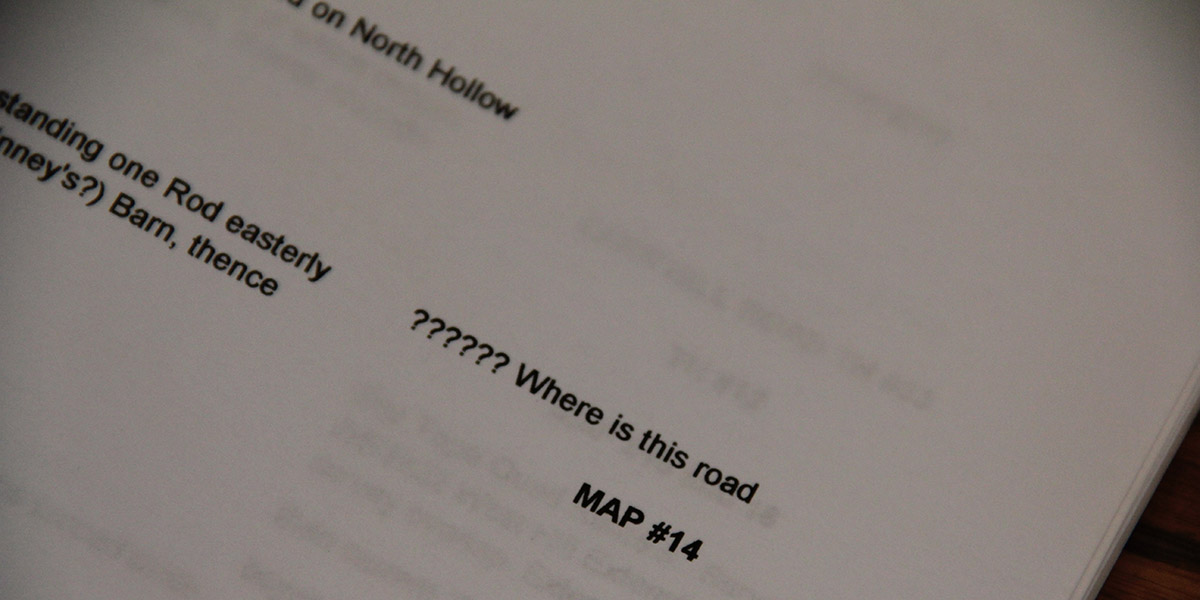

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: Photos by Simon Rouby for “

[Images: Photos by Simon Rouby for “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “