[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

I was in London earlier this month, primarily for another year of external exams at the Bartlett School of Architecture. This consists for the most part in meeting with a large group of students from different design units across the school for one-on-one presentations of their work; much of that work was incredibly interesting and worth sharing here.

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

This first project is a design for a new London Law Court, by Matthew Turner for Unit 12. The class, taught by Jonathan Hill, Elizabeth Dow, and Matthew Butcher, looked at what it called “the public private house,” with a focus on civic institutions and their relationship to the larger city.

In this case, that institution is a court of law.

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

The entire project is built around a set of stark spatial polarities set up between public and private, accuser and accused, guilty and innocent.

Circulation—the actual path a visitor might take to pass from one room to another, or from one part of the facility to the next, or even what can or cannot be seen from specific standpoints, such as the witness box or the judge’s robing chambers—is thus the building’s major organizing principle.

It is all about sequence, connection, and adjacency.

[Images: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Images: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

Even better, the project is a rigorous exploration of brick, a hugely overlooked material, including micro-studies of structural bricklaying patterns and surface effects.

[Image: Brick patterns from “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: Brick patterns from “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

Turner explained that different surface treatments show up throughout the building almost as a kind of signage or way-finding tool, such that particular patterns come to signify types of interior spaces throughout the complex—a public waiting area, for example, or spaces for the accused.

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

These pattern-studies are rendered in a style that makes them deeply reminiscent of Auguste Choisy.

[Images: Brick patterns from “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Images: Brick patterns from “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

Turner really went for it with the axonometry, cutting gorgeous sections through sites of extreme structural complexity that reveal slices of the interior that seem more like Cubist abstractions than actual building plans.

Yet, as his thesis voluminously demonstrates, all of the spaces nonetheless maintain both architectural and narrative coherence.

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

The passage of light, as can be seen in this next image, is also given symbolic or explanatory weight. As Turner writes, “Distances are compressed and spaces seem to step through each other. Spaces are attenuated, echoed and re-echoed before their sources are experienced. Light in the building does not signify divine truth and justice but instead its shadows and effects are hard to define.”

As they day progresses, the interior is like a clock, and “shadows become spaces within themselves.”

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

The thesis is immensely detailed, and these selections are barely sufficient as an introduction to Turner’s work. As a study of how architecture itself—that is, the careful and deliberate sequencing of spatial experience—can be used to instill narrative sensations of guilt, resolution, privacy, institutional respect, and so much more, it was really commendable.

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

[Image: From “The New London Law Court” by Matthew Turner, Bartlett School of Architecture, Unit 12].

I’ll hope to post a few more projects from the Bartlett over the next couple of days.

[Image: “St. Mark’s Place, with campanile, Venice, Italy,” via the Library of Congress].

[Image: “St. Mark’s Place, with campanile, Venice, Italy,” via the Library of Congress]. [Image: From United States of America, Plaintiff v. State of California,” December 15, 2014].

[Image: From United States of America, Plaintiff v. State of California,” December 15, 2014]. [Image: From United States of America, Plaintiff v. State of California,” December 15, 2014].

[Image: From United States of America, Plaintiff v. State of California,” December 15, 2014].

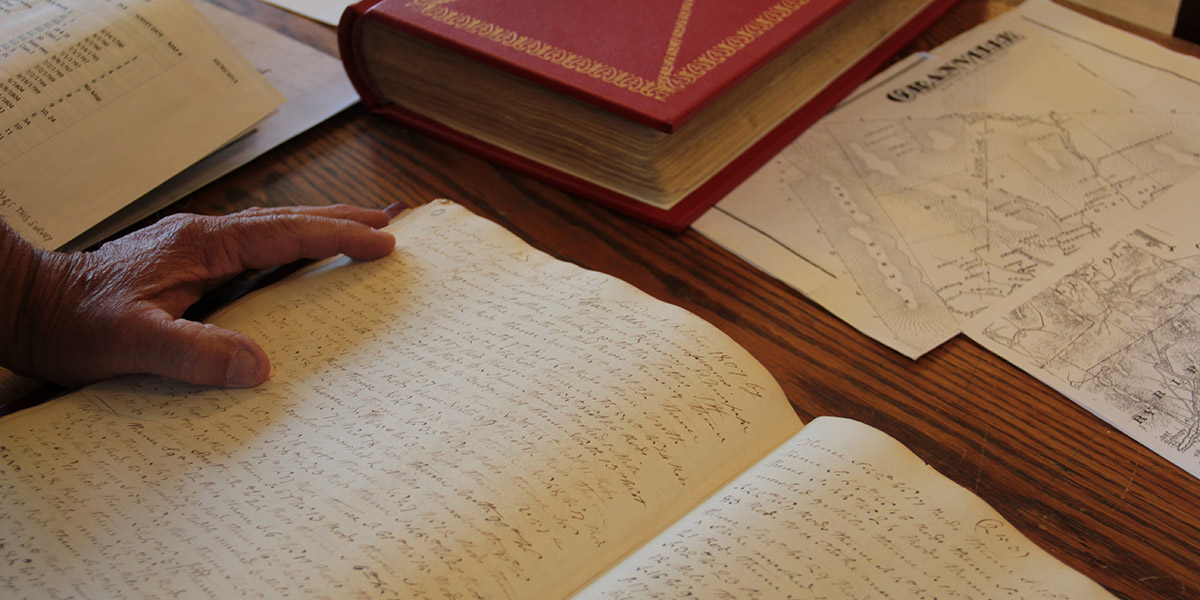

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

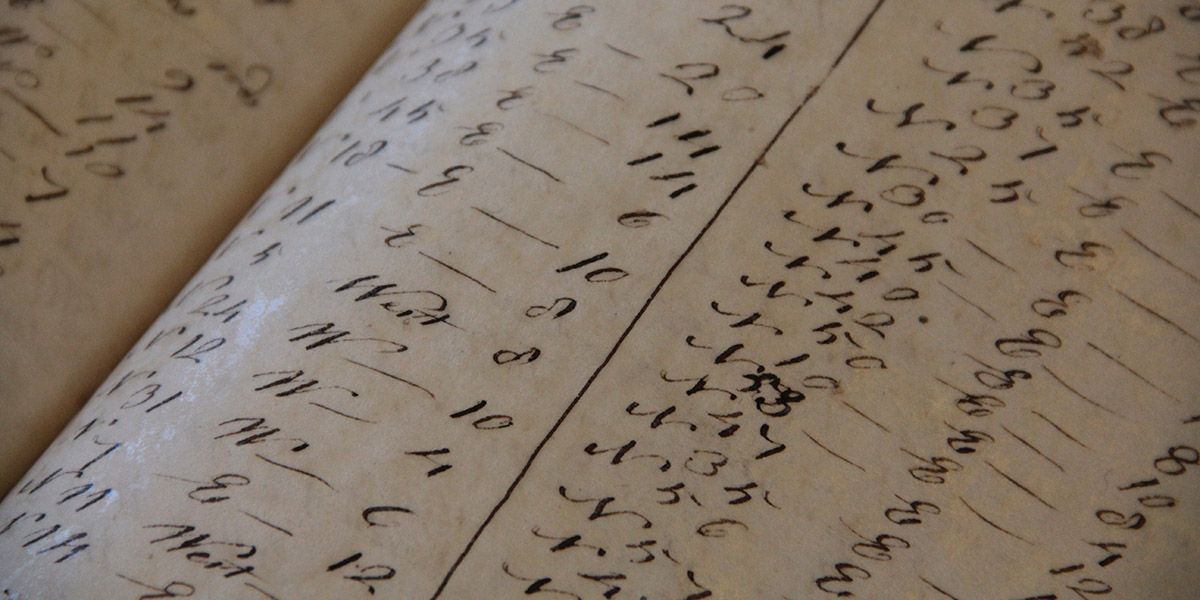

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

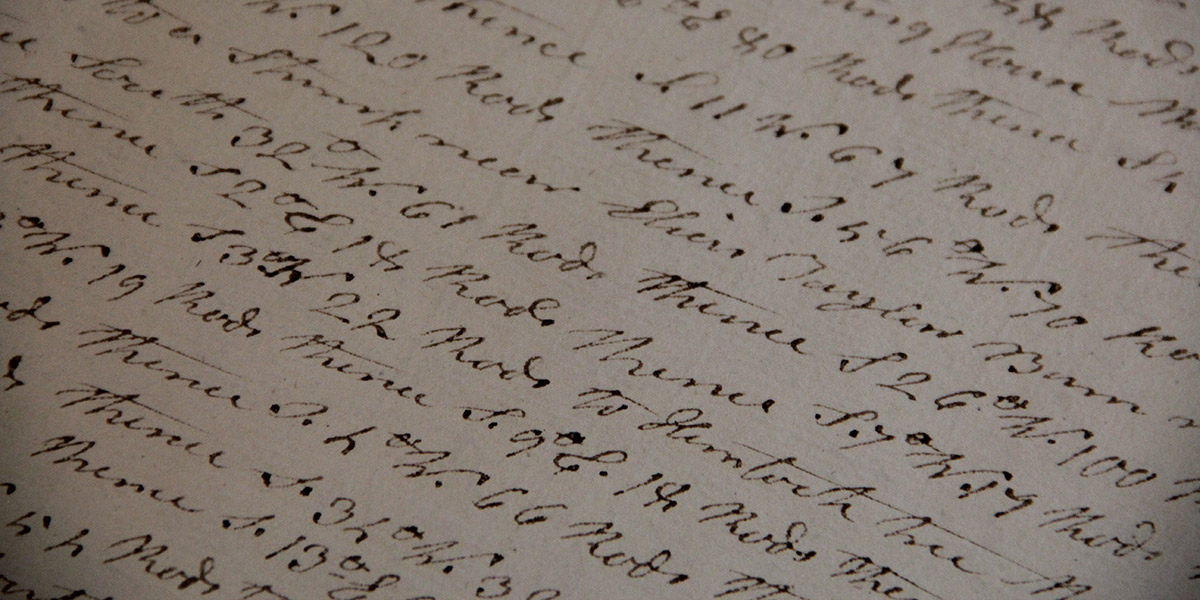

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

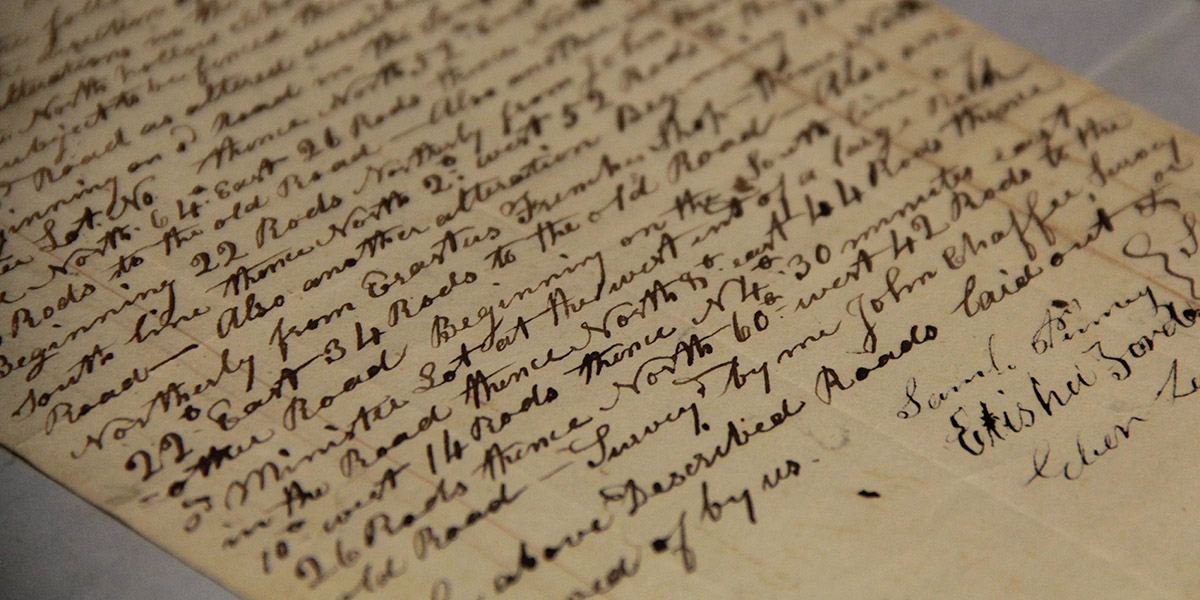

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

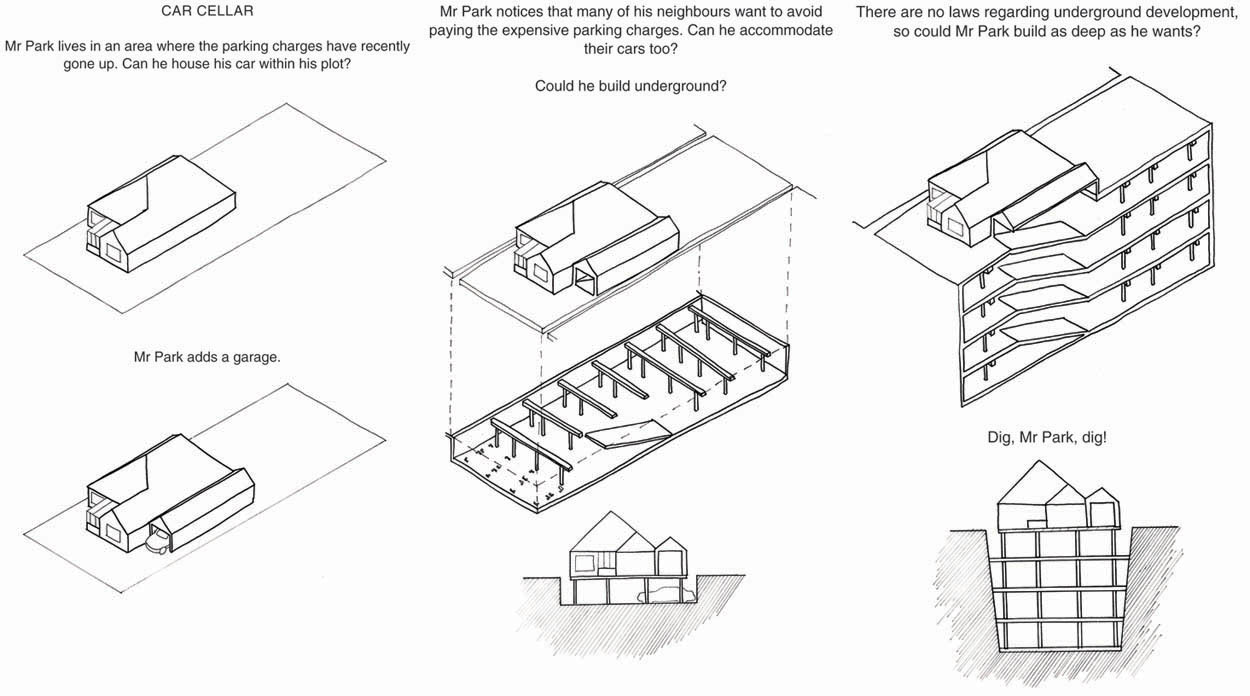

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of  [Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of