[Image: Fermont’s weather-controlling residential super-wall, courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

[Image: Fermont’s weather-controlling residential super-wall, courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

An earlier version of this post was published on New Scientist back in 2015.

Speaking at a symposium on Arctic urbanism, held at the end of January 2015 in Tromsø, Norway, architectural historian Alessandra Ponte introduced her audience to some of Canada’s most remote northern mining towns.

Ponte had recently taken a group of students on a research trip through the boreal landscape, hoping to understand the types of settlements that had been popping up with increasing frequency there. This included a visit to the mining village of Fermont, Quebec.

Designed by architects Norbert Schoenauer and Maurice Desnoyers, Fermont features a hotel, a hospital, a small Metro supermarket, and even a tourism bureau—for all that, however, it is run entirely by the firm ArcelorMittal, which also owns the nearby iron mine. This means that there are no police, who would be funded by the Canadian government; instead, Fermont is patrolled by its own private security force.

The town is also home to an extraordinary architectural feature: a residential megastructure whose explicit purpose is to redirect the local weather.

[Image: Wind-shadow studies, Fermont; courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

[Image: Wind-shadow studies, Fermont; courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

Known as the mur-écran or “windscreen,” the structure is nearly a mile in length and shaped roughly like a horizontal V or chevron. Think of it as a climatological Maginot Line, a fortification against the sky built to resist the howling, near-constant northern winds.

In any other scenario, a weather-controlling super-wall would sound like pure science fiction. But extreme environments such as those found in the far north are, by necessity, laboratories of architectural innovation, requiring the invention of new, often quite radical, context-appropriate building types.

In Fermont, urban climate control is built into the very fabric of the city—and has been since the 1970s.

[Image: Fermont and its iron mine, as seen on Google Maps].

[Image: Fermont and its iron mine, as seen on Google Maps].

Offworld boom towns

In a 2014 interview with Aeon, entrepreneur Elon Musk argued for the need to establish human settlements on other planets, beginning with a collection of small cities on Mars. Musk, however, infused this vision with a strong sense of moral obligation, urging us all “to be laser-focused on becoming a multi-planet civilization.”

Humans must go to Mars, he implored the Royal Aeronautical Society back in 2012. Once there, he proposed, we can finally “start a self-sustaining civilization and grow it into something really big”—where really big, for Musk, means establishing a network of towns and villages. Cities.

Of course, Musk is not talking about building a Martian version of London or Paris—at least, not yet. Rather, these sorts of remote, privately operated industrial activities require housing and administrative structures, not parks and museums; security teams, not mayors.

These roughshod “man camps,” as they are anachronistically known, are simply “cobbled together in a hurry,” energy reporter Russell Gold writes in his book The Boom. Man camps, Gold continues, are “sprawling complexes of connected modular buildings,” unlikely to be mistaken for a real town or civic center.

In a sense, then, we are already experimenting with offworld colonization—but we are doing it in the windswept villages and extraction sites of the Canadian north. Our Martian future is already under construction here on Earth.

[Image: Fermont apartments, design sketch, courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

[Image: Fermont apartments, design sketch, courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

Just-in-time urbanism

Industrial settlements such as Russell Gold’s fracking camps in the American West or those in the Canadian North are most often run by subsidiary services corporations, such as Baker Hughes, Oilfield Lodging, Target Logistics, or the aptly named Civeo.

The last of these—whose very name implies civics reduced to the catchiness of an IPO—actually lists “villages” as one of its primary spatial products. These are sold as “integrated accommodation solutions” that you can order wholesale, like a piece of flatpak furniture, an entire pop-up city given its own tracking number and delivery time.

Civeo, in fact, recently survived a period of hedge-fund-induced economic turbulence—but this experience also serves as a useful indicator for how the private cities of the future might be funded. It is not through taxation or local civic participation, in other words: their fate will instead be determined by distant economic managers who might cancel their investment at a moment’s notice.

A dystopian scenario in which an entire Arctic—or, in the future, Martian—city might be abandoned and shut down overnight for lack of sufficient economic returns is not altogether implausible. It is urbanism by stock price and spreadsheet.

[Image: Constructing Fermont, courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

[Image: Constructing Fermont, courtesy Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University].

Consider the case of Gagnon, Quebec. In 1985, Alessandra Ponte explained, the town of Gagnon ceased to exist. Each building was taken apart down to its foundations and hauled away to be sold for scrap. Nothing was left but the ghostly, overgrown grid of Gagnon’s former streets, and even those would eventually be reabsorbed into the forest. It was as if nothing had been there at all. Creeks now flow where pick-up trucks stood thirty years ago.

In the past, abandoned cities would be allowed to molder, turning into picturesque ruins and archaeological parks, but the mining towns of the Canadian north meet an altogether different fate. Inhabited one decade and completely gone the next, these are not new Romes of the Arctic Circle, but something more like an urban mirage, an economic Fata Morgana in the ice and snow.

Martian pop-ups

Modular buildings that can be erased without trace; obscure financial structures based in venture capital, not taxation; climate-controlling megastructures: these pop-up settlements, delivered by private corporations in extreme landscapes, are the cities Elon Musk has been describing. We are more likely to build a second Gagnon than a new Manhattan at the foot of Olympus Mons.

Of course, instant prefab cities dropped into the middle of nowhere are a perennial fantasy of architectural futurists. One need look no further than British avant-pop provocateurs Archigram, with their candy-colored comic book drawings of “plug-in cities” sprouting amidst remote landscapes like ready-made utopias.

But there is something deeply ironic in the fact that this fantasy is now being realized by extraction firms and multinational corporations—and that this once radical vision of the urban future might very well be the perfect logistical tool that helps humankind achieve a foothold on Mars.

In other words, shuttles and spacesuits were the technologies that took us to the moon, but it will be cities that take us to new worlds. Whether or not any of us will actually want to live in a Martian Fermont is something that remains to be seen.

[Image: “St. Mark’s Place, with campanile, Venice, Italy,” via the Library of Congress].

[Image: “St. Mark’s Place, with campanile, Venice, Italy,” via the Library of Congress].

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image by

[Image by  [Image by

[Image by

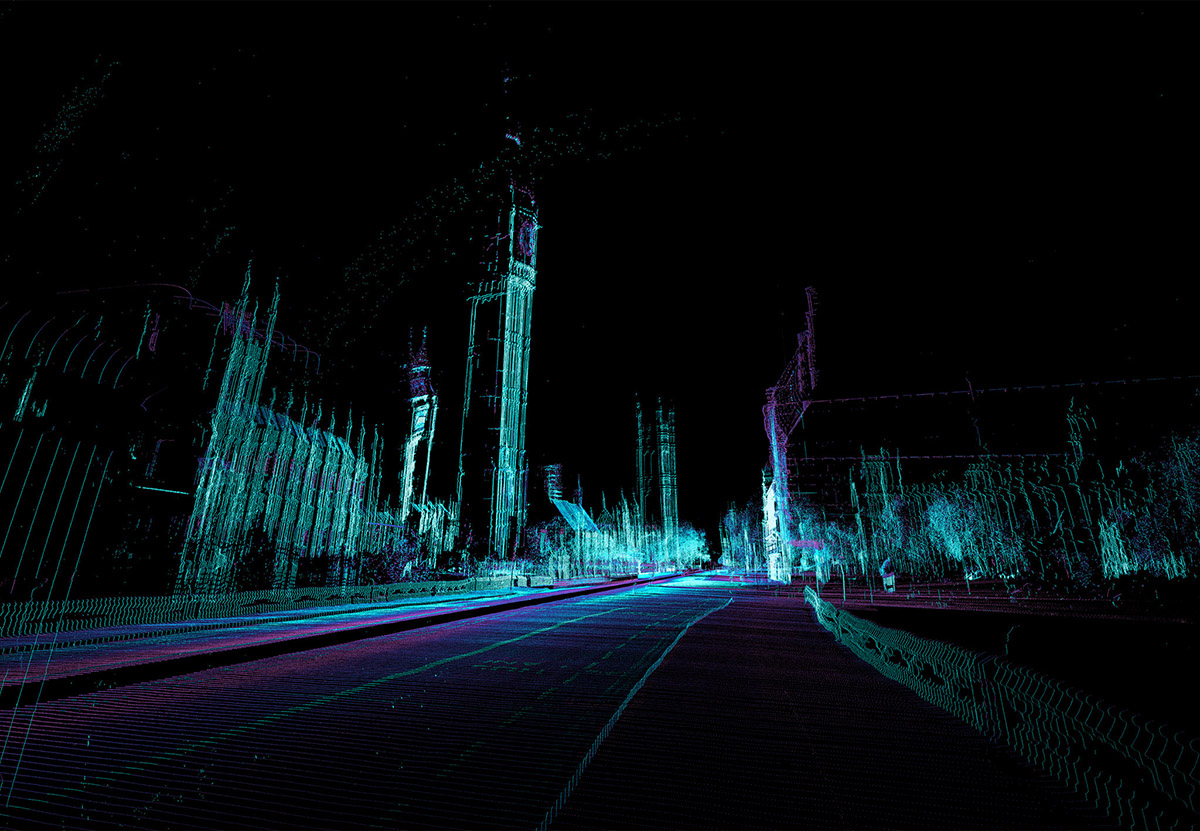

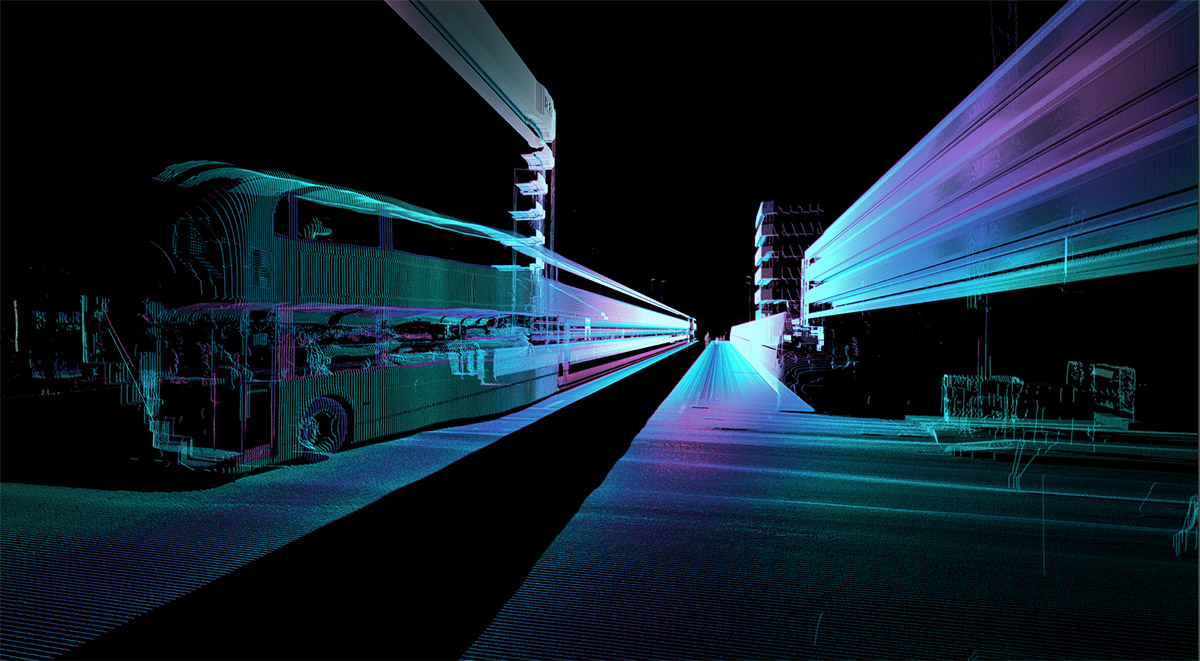

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

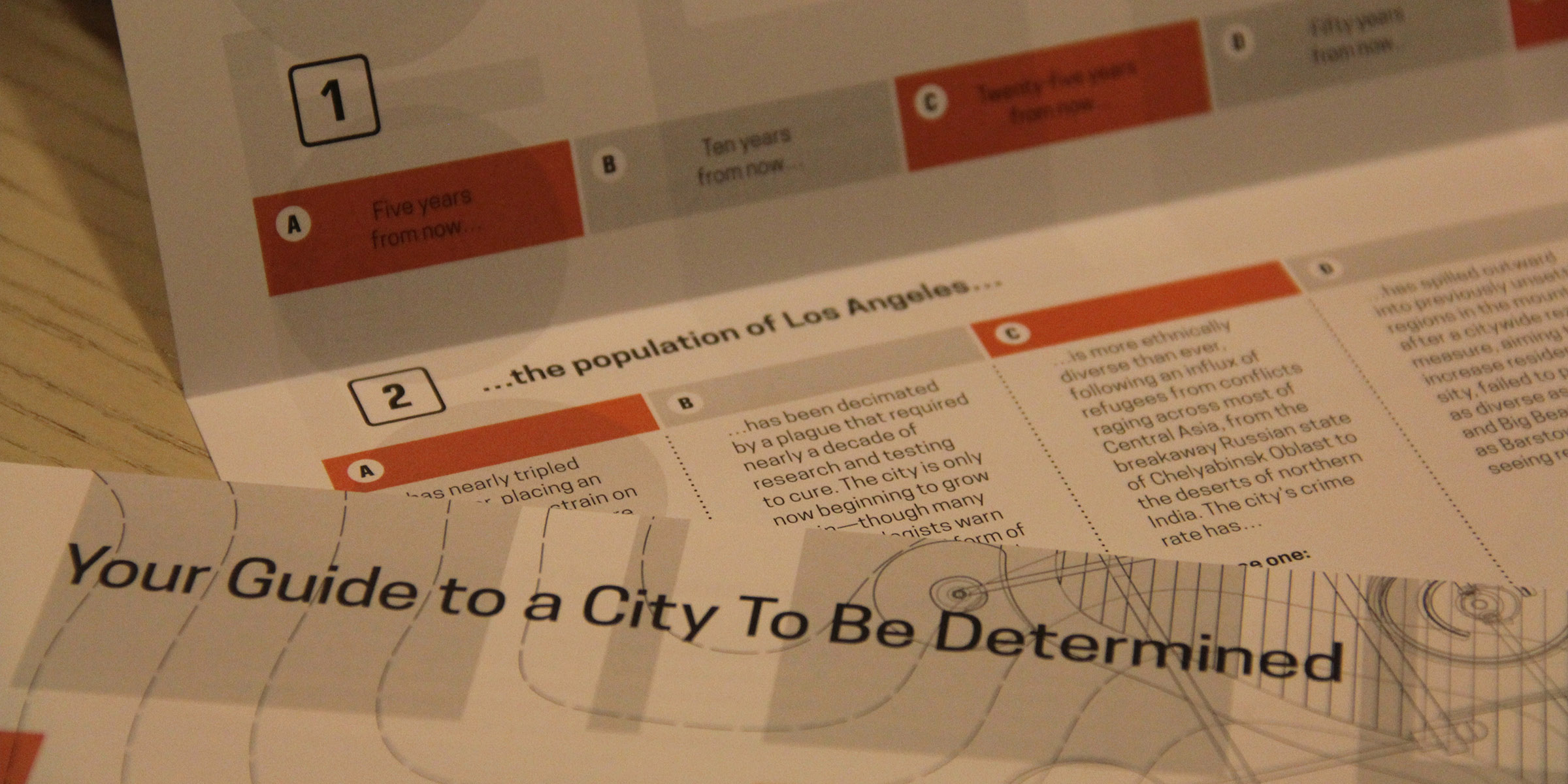

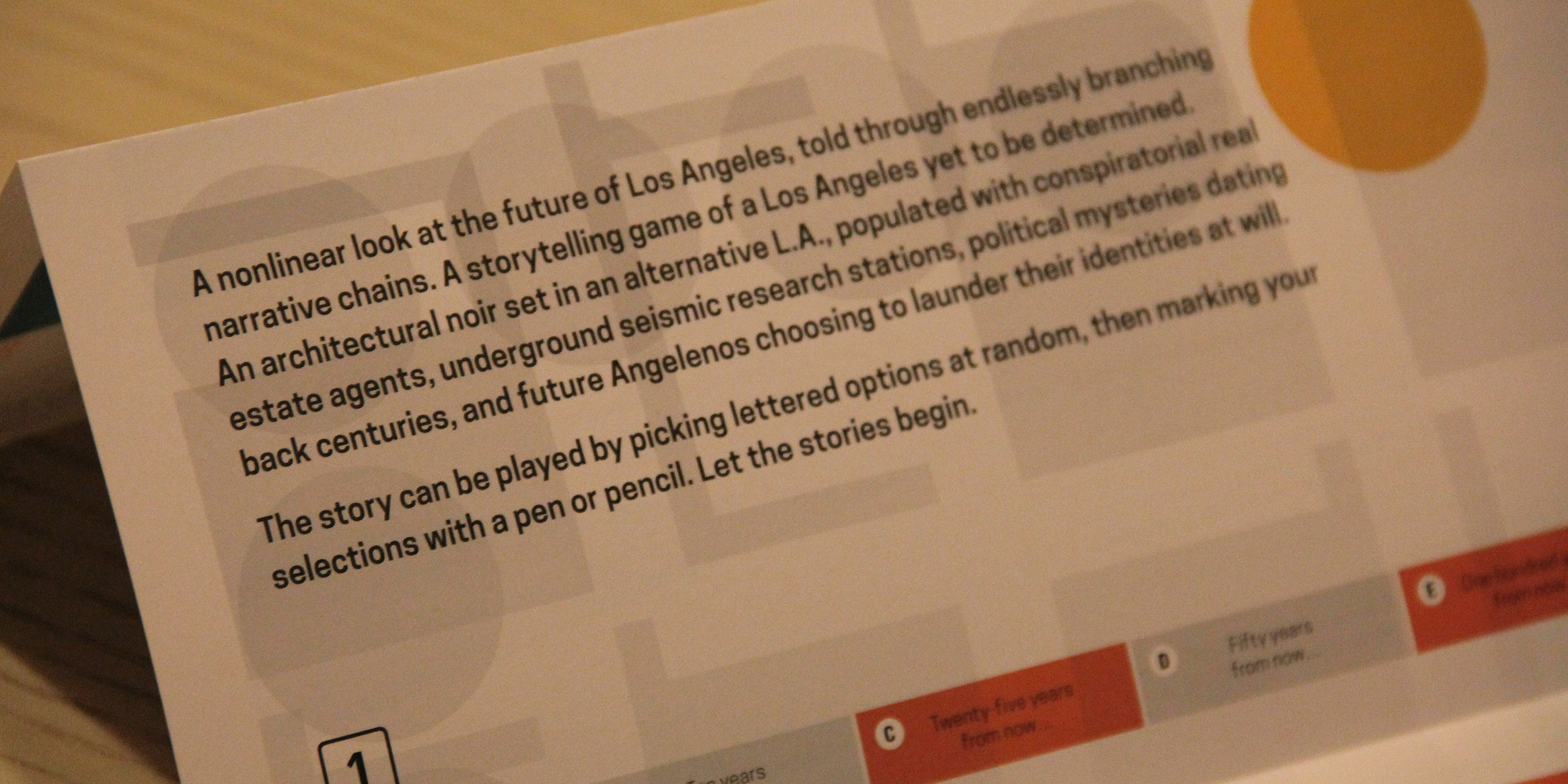

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

This is purely promotional, but I wanted to mention that I am up in San Francisco for two nights to speak as part of

This is purely promotional, but I wanted to mention that I am up in San Francisco for two nights to speak as part of

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Abandoned Packard plant in Detroit, via

[Image: Abandoned Packard plant in Detroit, via