[Image: Via TechCrunch].

[Image: Via TechCrunch].

There was finally something interesting to read about Pokémon Go. The game—which involves overlaying the physical world with a grab-bag of exotic creatures that players attempt to capture for points—might help catalyze a new form of virtual urban zoning.

In England, BuzzFeed reported earlier this week, “one person has been so unsettled by strangers turning up at their house that they’ve been forced to ask their member of parliament to intervene.” Apparently, the game’s virtual characters have been showing up within this person’s property lines, which has been “attracting people from far and wide to come and do battle.”

The peeved constituent presumably wants to establish some sort of legal mechanism for preventing uninvited virtual inhabitants from popping up on his or her private property.

[Image: Altered photo of an American front lawn, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Altered photo of an American front lawn, via Wikipedia].

In the U.S., meanwhile, a New Jersey man has also had enough of these sorts of pixellated guests.

As Kashmir Hill writes for Fusion, “So many people started showing up around [the New Jersey man’s] house, smartphones in hand, hunting Pokémon that he is now suing the makers of the game for creating a nuisance and unjustly enriching themselves by using his backyard as a virtual home for the game’s cartoon creatures.”

In a sense, the game’s designers are operating an illegal—albeit virtual—business on his property.

The New Jersey man’s legal complaint alleges that he “became aware that strangers were gathering outside of his home, holding up their mobile phones as if they were taking pictures. At least five individuals knocked on Plaintiff’s door, informed Plaintiff that there was a Pokémon in his backyard, and asked for access to Plaintiff’s backyard in order to ‘catch’ the Pokémon.”

Trespassing, unlicensed business activity, illegal occupancy, even burglary—as Hill points out, this has led to a rather fascinating challenge to the limits of personal property rights.

It is “quite a novel lawsuit,” she writes, referring specifically to the New Jersey case. “It is laughable, on the one hand, yet it does raise interesting questions around who owns the augmented reality space overlaid on people’s real world properties. When you own land, there are limits to how far above and below your house you own. A new question would be the extent of your rights to the new dimension on top of your property that is augmented reality.”

For Hill, this goes on to raise a series of related questions, including, “if augmented reality really catches on, and an internet environment overlaid on our real world surroundings becomes common, what will be the rules around using that augmented space? Could anyone put a virtual billboard on the front of your house or would they need your permission?”

Could you sell, lease, or subdivide the digital rights to your own home, yard, or lobby?

Could you extract a toll, tax, or commission from virtual usage?

[Image: “With the success of Pokémon Go, we set out to discover if any of the little monsters were hiding within the walls of our own L.A. Times newsroom.” Were those little monsters digitally trespassing? Photo via the L.A. Times].

[Image: “With the success of Pokémon Go, we set out to discover if any of the little monsters were hiding within the walls of our own L.A. Times newsroom.” Were those little monsters digitally trespassing? Photo via the L.A. Times].

A while back, we looked at zoning rules in the U.K., hoping to learn what those rules might reveal about the extent to which everyday citizens can use, or even fundamentally transform, personal real estate. What can the state regulate—what can zoning rules control—versus what a private property owner commands? What about digitally?

These Pokémon Go examples suggest something altogether more ominous, I might suggest, wherein a digital entertainment company could prove to have de facto access to your yard, your car, your front stoop, your place of business, using any one of those merely as a stage or platform for passive economic activity.

How much would I love to read a Supreme Court decision—and its dissent!—about these very questions, posing an absolute outside limit to personal digital property rights, where virtual homesteads begin and end, or the extent to which we have the right to populate other people’s space with augmentations and intrusions.

[Image: Skid Row, Los Angeles, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Skid Row, Los Angeles, via Wikipedia].

Briefly, it’s worth adding that this could also have urban-scale implications.

As Curbed L.A. pointed out this week, Los Angeles “is a veritable menagerie of diverse and unusual Poké-creatures,” which means that “the city may soon be overrun with Poké-tourists,” people from diverse geographic backgrounds hoping to capture high-value targets.

Pokémon Go will disappear from public memory relatively soon, of course, yet it is all but guaranteed to be replaced by other augmented-reality games that also rely on a quote-unquote real, physical location to determine the strategic value of player actions.

To what extent, then, will entire urban entities such as Los Angeles seek to collaborate with, or even directly fund, virtual inhabitants—virtual landmarks, virtual historic sites, virtual destinations—and what are the rules or regulations that might apply to them?

Finally—as anyone who has read Delirious New York or is familiar with the work of Hugh Ferriss knows—cities are fundamentally shaped by zoning laws, literally down to the shadows cast by individual buildings. What, then, might digital or virtual zoning actually look like? How might it shape urban environments to come?

What, as Kashmir Hill asked, is “the extent of your rights to the new dimension on top of your property that is augmented reality”?

*Update* In a slightly expanded version of this post syndicated by Motherboard, I point out that Thailand is already looking “to restrict zoning for the Pokémon Go game after receiving several complaints from people who are disturbed by the trainers, or players, of the game.”

The proposed blocklist would begin with sites of national security, removing them from the field of potential gameplay. However, it is not hard to imagine private citizens using their own political influence to help determine which homes—let alone which streets or entire neighborhoods—would be added to the no-game zone. Think of it as geofencing as a form of urban design.

More over at Motherboard.

(Thanks to @AnthonyAdler for tweeting about “virtual environment policy” a few days ago).

[Image: Boston, courtesy of the

[Image: Boston, courtesy of the

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Altered photo of an American front lawn, via

[Image: Altered photo of an American front lawn, via  [Image: “With the success of Pokémon Go, we set out to discover if any of the little monsters were hiding within the walls of our own L.A. Times newsroom.” Were those little monsters digitally trespassing? Photo via the

[Image: “With the success of Pokémon Go, we set out to discover if any of the little monsters were hiding within the walls of our own L.A. Times newsroom.” Were those little monsters digitally trespassing? Photo via the  [Image: Skid Row, Los Angeles, via

[Image: Skid Row, Los Angeles, via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: A sidewalk corner in Los Angeles, albeit not the one for sale; via Google Street View].

[Image: A sidewalk corner in Los Angeles, albeit not the one for sale; via Google Street View].

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

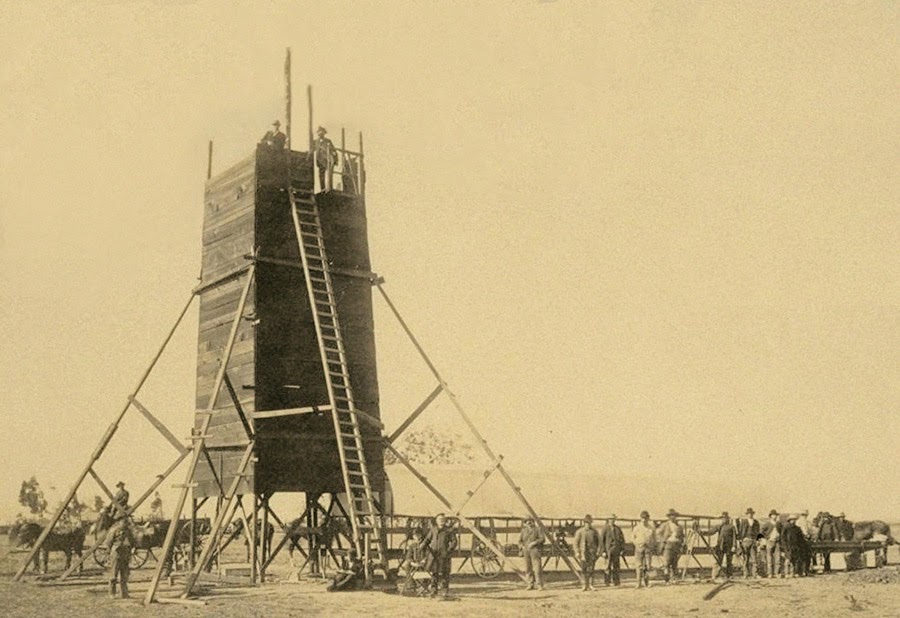

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.

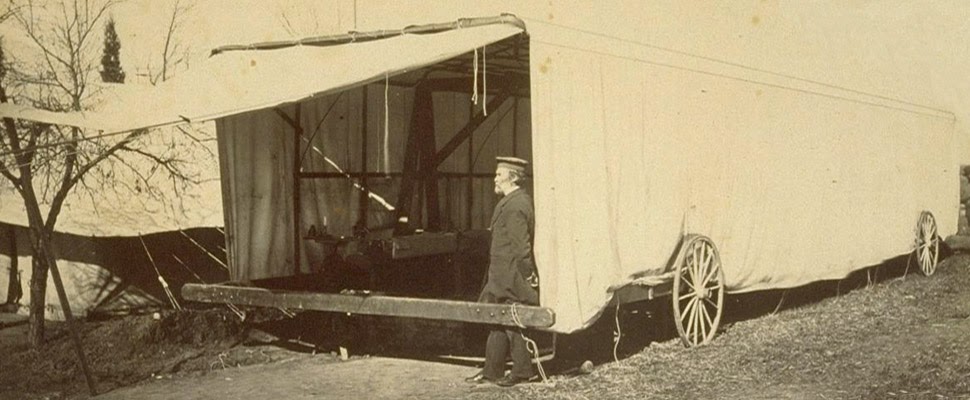

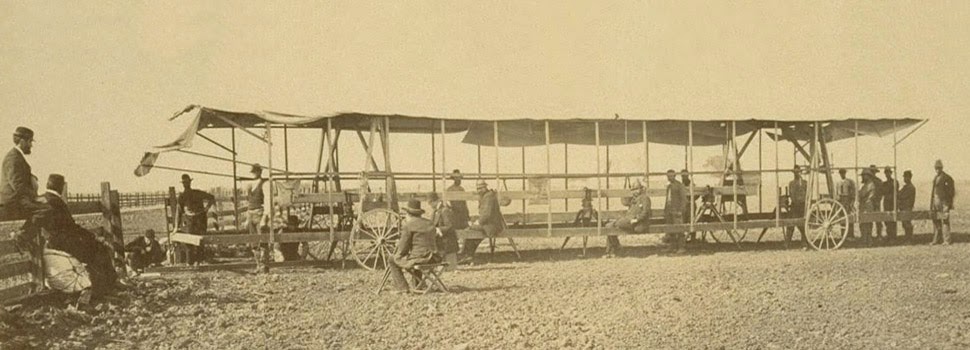

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.  The “moveable tent or ‘

The “moveable tent or ‘ The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the

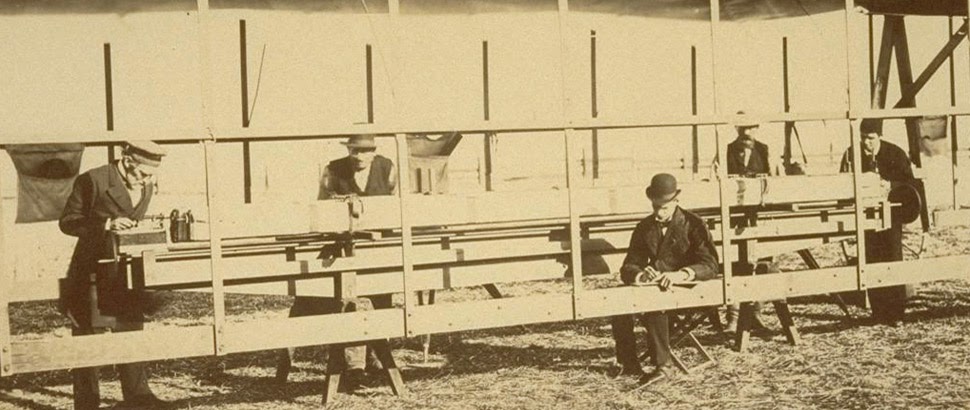

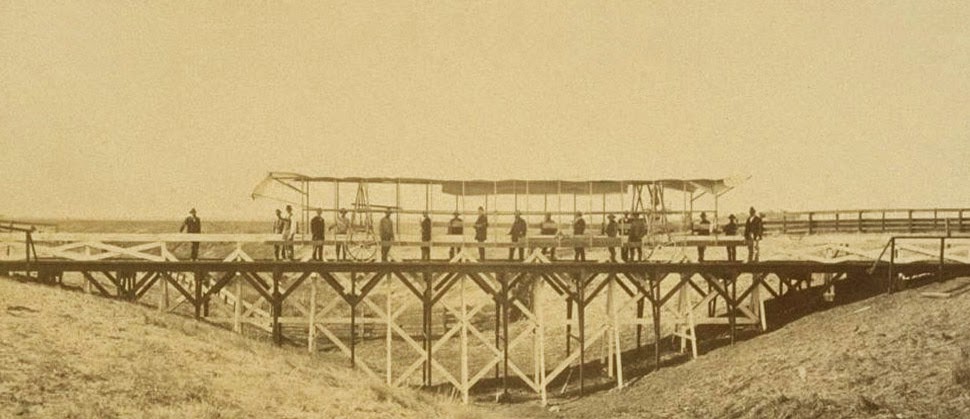

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the  In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.  That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land. Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.