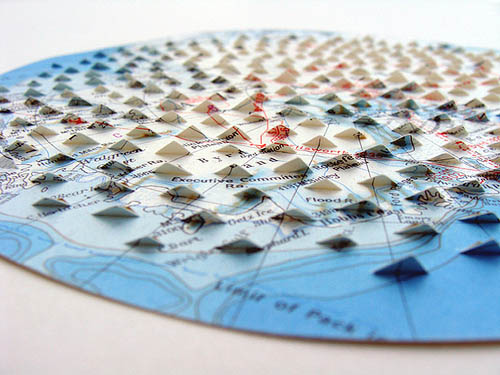

[Image: “The Empty Quarter (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Image: “The Empty Quarter (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

I’m thrilled to have some map collages in the latest issue of the Yale Review.

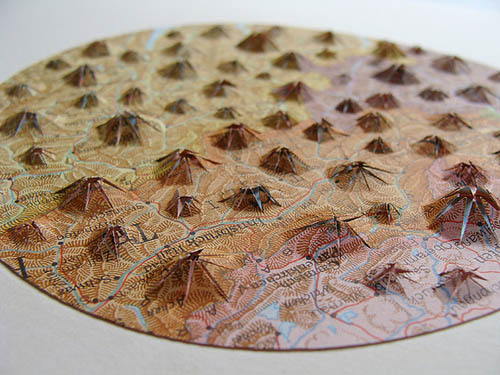

[Image: “Groundwater Grids (North Dakota)” (2020), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Image: “Groundwater Grids (North Dakota)” (2020), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

I started making these during lockdown, as part of a larger (and, to be honest, now doomed-feeling) graphic novel project using public domain U.S. Geological Survey maps as the main material.

[Images: “Keys II (Florida)” (2020) and “Keys I (Florida)” (2020), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; the source maps for these are particularly interesting, because they utilize satellite photography.]

[Images: “Keys II (Florida)” (2020) and “Keys I (Florida)” (2020), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; the source maps for these are particularly interesting, because they utilize satellite photography.]

The images in this post include a few collages not published in the Yale Review, but click through for the full issue’s broad selection of poetry, essays, fiction, and more.

[Images: “Morse Landscape II (Louisiana)” and “Morse Landscape I (Louisiana)” (2021), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Images: “Morse Landscape II (Louisiana)” and “Morse Landscape I (Louisiana)” (2021), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

And huge, huge thanks to Eugenia Bell for the editorial interest!

[Images: Various collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Images: Various collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

If you’re looking for someone to design a book cover or album cover or event poster, hit me up.

[Image: “Terrestrial Astronomy (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; it’s a pedestrian observation, but inverting the color scheme of geological maps makes them look like maps of stars.]

[Image: “Terrestrial Astronomy (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; it’s a pedestrian observation, but inverting the color scheme of geological maps makes them look like maps of stars.]

[Image: Boston, courtesy of the

[Image: Boston, courtesy of the  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Saxenburgh Island, from Andrew Pekler’s

[Image: Saxenburgh Island, from Andrew Pekler’s  [Image: Antillia Island, from Andrew Pekler’s

[Image: Antillia Island, from Andrew Pekler’s  [Image: Hunter Island, from Andrew Pekler’s

[Image: Hunter Island, from Andrew Pekler’s  [Image: Screen-grab from

[Image: Screen-grab from

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by

[Images: By

[Images: By