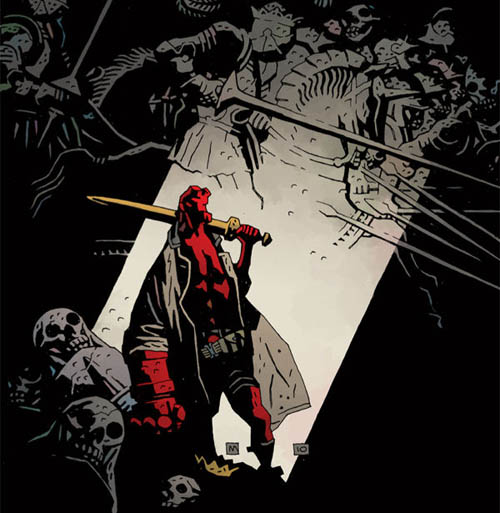

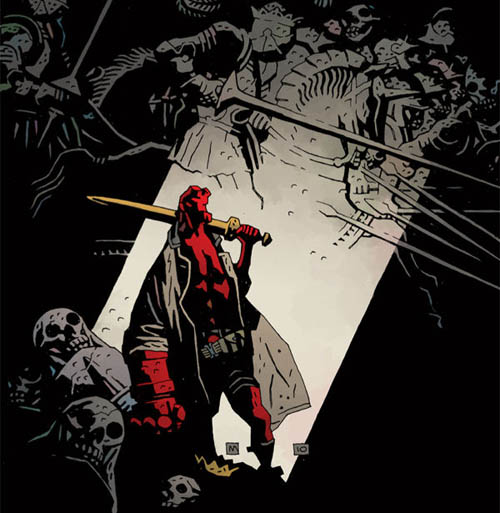

[Image: From a cover by Mike Mignola for Hellboy: The Storm, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Image: From a cover by Mike Mignola for Hellboy: The Storm, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

For half a decade now, I’ve been an avid fan of the work of Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy, the B.P.R.D., and Abe Sapien, among many others, including, most recently, the new series Witchfinder and Baltimore. When my wife and I moved back to California last August, the heaviest boxes were the ones I’d stuffed full of graphic novels by Mike Mignola, which I’ve been hoarding whenever money allows. It’s become an addiction: the incredible old castle interiors and snowbound mountain landscapes of Conqueror Worm, the Mesoamerican design motifs emerging like mazes from pitch black walls of shadow in Seed of Destruction, the graveyards of ships wrecked on rocks before coastal citadels in Strange Places, and all of it shot through with Mignola’s dark sarcasm and humor.

Mignola’s work outlines an endlessly captivating world, somewhere between H.P. Lovecraft and Norse epics, Dracula—as rewritten by Jules Verne—and the Discovery Channel. Equal parts archaeology and horror fiction, Indiana Jones and The Thing, heretical mythology and conspiracy science, once Mignola’s work digs its plot lines and landscapes into you, it seems impossible to shake.

The buildings, terrains, and spaces Mignola’s plots take place within are equally extraordinary: there are remote, factory-like castles north of the Arctic Circle, wired floor-to-ceiling with arcane laboratory equipment; maritime plagues and New England shipwrecks; intelligent geological formations in space, larger than planets, signaling down to Army radar stations at the end of World War II; abandoned mines and ruined churches; Mayan fragments mounted on the luxurious, candlelit walls of Alpine mansions; Nazi conspiracies and fallen astronauts; derelict Victorian houses wrapped in fog on the coastal moor.

In addition to his prolific work as a graphic artist, Mignola has served as a visual consultant on three films by Guillermo Del Toro, each better than the previous: Blade II, Hellboy, and Hellboy 2: The Golden Army. With Christopher Golden, he is co-author of the recent novel Baltimore; he has drawn covers for Conan the Barbarian, X-Men, Aliens versus Predator, Superman, and dozens of others; and his Eisner Award-winning graphic novel, The Amazing Screw-On Head and Other Curious Objects, was republished in 2010.

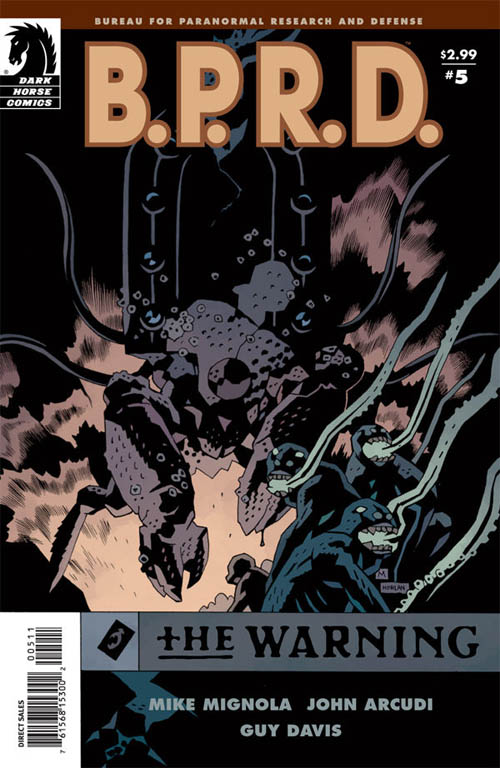

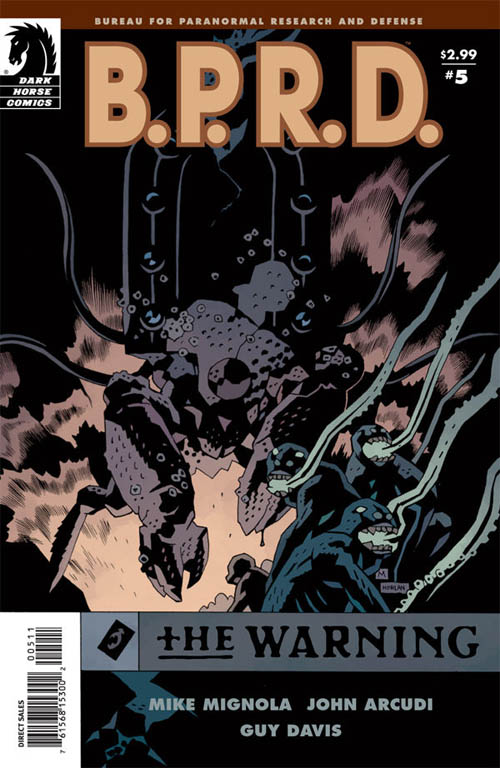

[Image: A cover by Mike Mignola for B.P.R.D.: The Warning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Image: A cover by Mike Mignola for B.P.R.D.: The Warning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

Mike Mignola recently talked to BLDGBLOG about his interests, including H.P. Lovecraft, wartime landscapes, and houses on the verge of collapse, with a specific focus on what it means to draw spaces of horror and mythology. We spoke by phone.

• • •BLDGBLOG: I’ve long been interested in how people outside of the architectural world use buildings, landscapes, cities, and other spaces as a way to frame mood or character. Your own work, from

Hellboy and the

B.P.R.D. to

Abe Sapien and

Baltimore, is full of ruined churches, old battlefields, houses with flooded basements, warped floors and empty attics, and other straightforwardly Gothic landmarks. What draws you to these particular building types and locations, and how do these settings then affect your plot lines and characters?

Mike Mignola: Well, I am unapologetically old-fashioned in my use of Gothic settings. Ever since I was a kid, when I read Dracula, I’ve just loved those kinds of places.

I have never done a story in a shopping mall because, even if I’m not drawing it myself, I don’t want to see somebody draw a shopping mall. In the Hellboy world, and in other things I’ve done, those places almost don’t exist. When I do Eastern Europe—and I’ve been to Eastern Europe, and I’ve seen the shopping malls and the god-awful housing projects and things, and there are horror stories that take place in there, I have no doubt—but I gravitate toward the classic, clichéd, spooky places, whether they truly exist in this world or not.

But that’s the world I want to live in, and it’s the world my characters live in.

[Images: (left) A cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt; (middle) from the cover of Rex Mundi by Arvid Nelson and Juan Ferreyra; (right) a cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt. All artwork by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Images: (left) A cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt; (middle) from the cover of Rex Mundi by Arvid Nelson and Juan Ferreyra; (right) a cover from Hellboy: The Wild Hunt. All artwork by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: Beyond shopping malls, I’m curious if there are other sorts of anti-Mignola settings, so to speak—places where you just could never set a story, even if it’s just a bank in London.

Mignola: I’m not going to do any stories that I don’t want to draw—and, for the most part, those are places that also just aren’t particularly interesting for me to write about.

It’s interesting, because the spin-off book from Hellboy—B.P.R.D.—is written by another writer. I have some involvement there, but the books are written by somebody else. You look at that book now, and the current storyline takes place in a trailer park. It’s entirely made of the places I have no interest in writing about—but the other writer doesn’t have my overwhelming love of the Gothic. He’s a much more modern type of writer, so we differ on our choice of locations.

But, now, a haunted bank? You know, that would be cool—but it would have to be a really, really old bank. And preferably a bank that’s been abandoned for a bunch of years, so you have cobwebs and things. I just like those old, spooky settings.

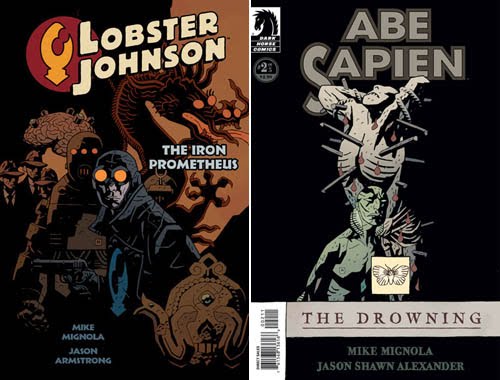

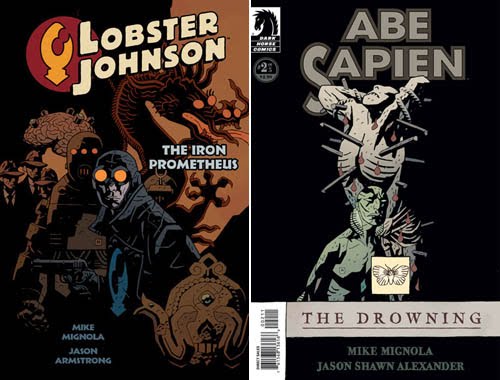

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Lobster Johnson: The Iron Prometheus and Abe Sapien: The Drowning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Lobster Johnson: The Iron Prometheus and Abe Sapien: The Drowning, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: There’s a maritime undercurrent in much of your work, including Hellboy, Abe Sapien, and, of course, the plague ships of Baltimore. It’s a kind of maritime Gothic—a world of shipwrecks and sea monsters and lighthouses on foggy coasts.

Mignola: Shipwrecks are great—but ships in general, even when they’re not wrecked, as long as they’re old school sailing ships, are wonderfully Gothic. I don’t know that I’ve done a lot of stories—if any stories—with ships that are 20th-century ships. I like the romance and the spookiness and the tragedy that goes with that old time sea travel. Those stories pertaining to ships are huge. I love them. They’re a big genre within ghost story fiction.

One of my favorite authors—a guy named William Hope Hodgson—most of his career, or a large chunk of his career, was writing supernatural ships-at-sea stories. There’s a romance in that old school, Gothic-y way to the world. And, basically, everything I love, I try to bring into my work. This world, or these different worlds that I’m creating, are entirely made of stuff that I love and think about.

Everything that I’m a fan of, I want to put into these worlds.

[Images: Photos by Fred R. Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times].

[Images: Photos by Fred R. Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times].

BLDGBLOG: Last summer, construction workers uncovered the remains of an old ship buried in the mud beneath the World Trade Center site in Manhattan, and some of the photos later printed in the New York Times, taken by Fred R. Conrad, were like something straight out of a Mike Mignola story. In some ways, it seemed like the perfect opening scene for a film version of Abe Sapien or for Hellboy 3—as if beneath, or even inside, the island of Manhattan we find this rotting, Gothic, semi-forgotten maritime history.

Mignola: Yeah, you know, I love history. I’m not a scholar—I’m not an historian—but it’s mostly because I just don’t have time. There’s too much other stuff I’m trying to keep on top of. But I love that sense of the buried past.

[Image: From Hellboy: The Wild Hunt, written by Mike Mignola and Scott Allie; art by Duncan Fegredo and Patric Reynolds. Courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Image: From Hellboy: The Wild Hunt, written by Mike Mignola and Scott Allie; art by Duncan Fegredo and Patric Reynolds. Courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: I want to go back to the idea of setting. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where a setting that you’ve devised for a certain storyline simply doesn’t work for Hellboy, say, so you have to use—or even invent—another character, or an entirely different plot, in order to use the architecture? In other words, how does setting—that is, how can architecture—affect plot and characterization, and vice versa?

Mignola: Well, part of the Baltimore series we’re doing now takes place on a World War 1 battlefield. I love that setting. It’s wonderfully rich in horror and drama—but it’s really hard for me to do a Hellboy story that takes place on a World War 1 battlefield. I could do it, and I’ve done stories like that, where it’s a time travel -slash- dream kind of thing—in fact, in an upcoming issue of Hellboy, I do have another character who I’ve tied to World War 1—but, to do it right, you need a World War 1 story.

So I came up with the Baltimore novel—and, now, the comic—to address that.

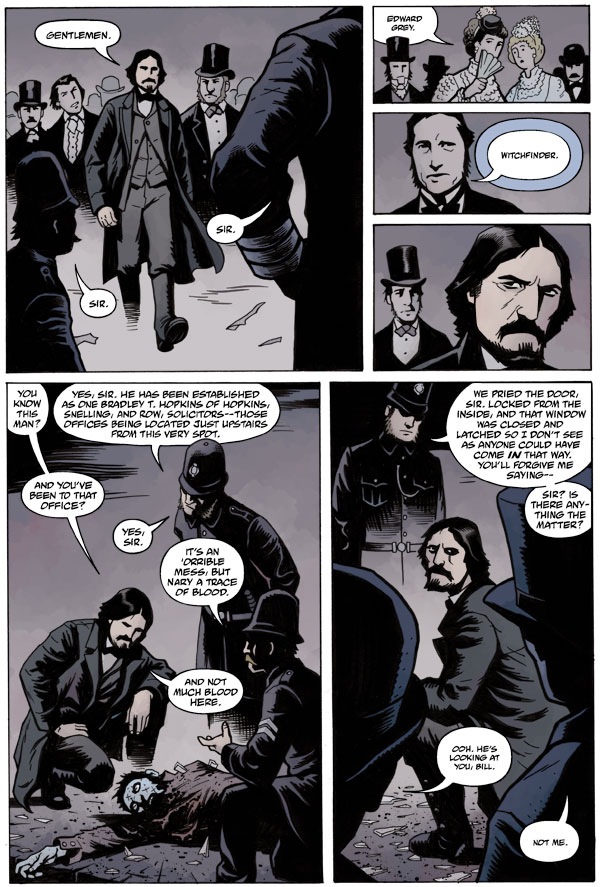

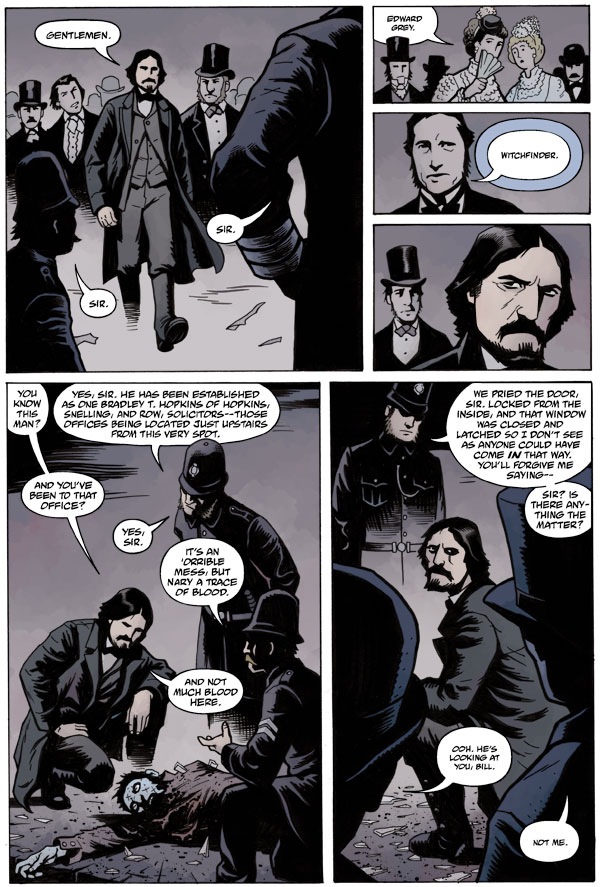

There’s also Victorian London, which I love. I came up with a Hellboy story once where he kind of time-traveled back to Victorian London—it seemed a little goofy to me—but I knew that I wanted to do Victorian London, so it was just a question of making a character who functioned in that world.

In a lot of cases, though, I am creating characters in order to see these places—these times, these settings. But, from the very beginning, I’ve known what kinds of stories I’ve wanted to do—so it’s also a question of finding the character who belongs to that world, as an excuse to draw that world.

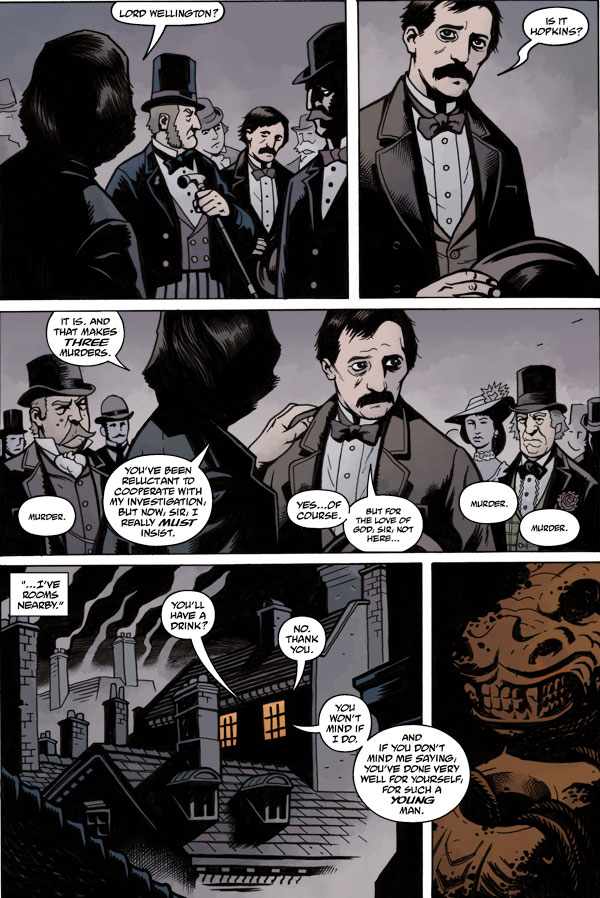

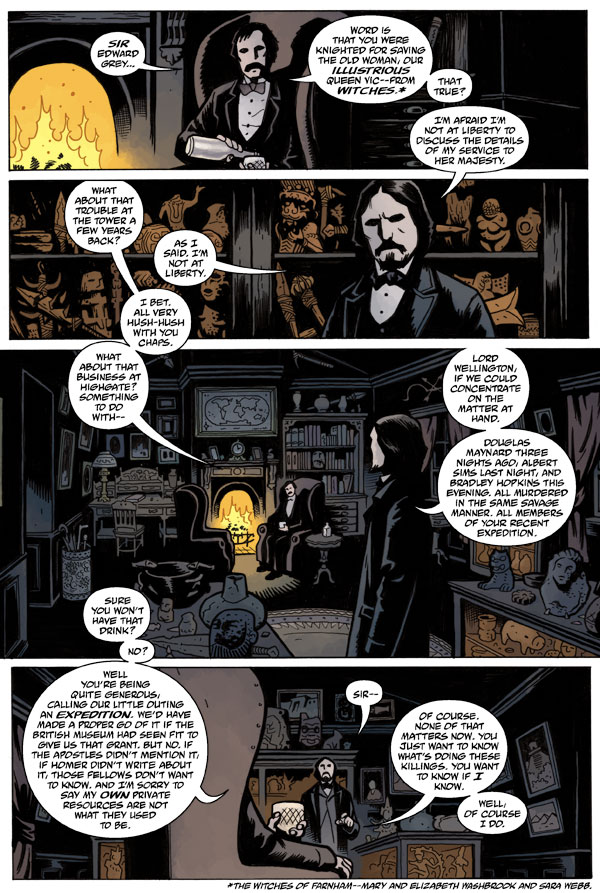

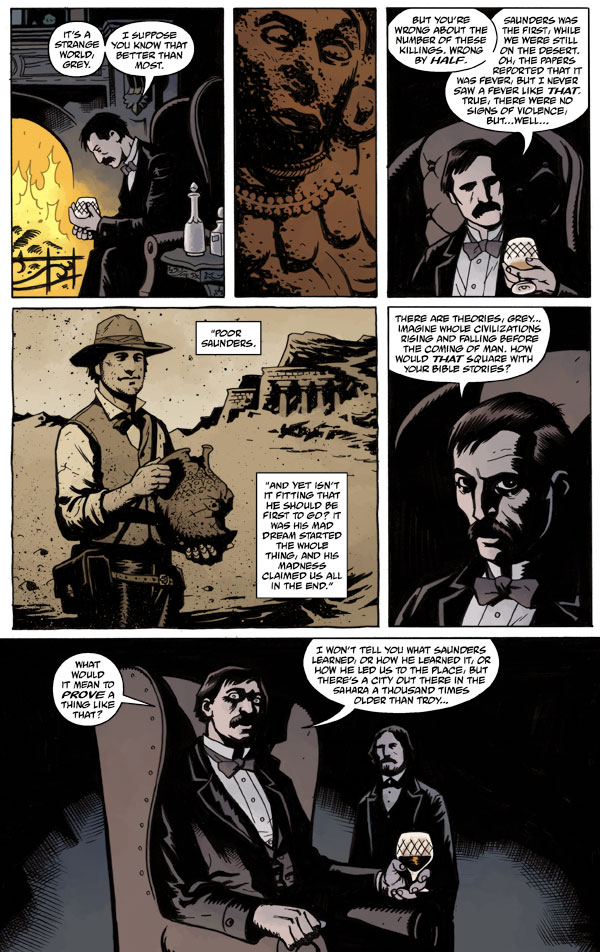

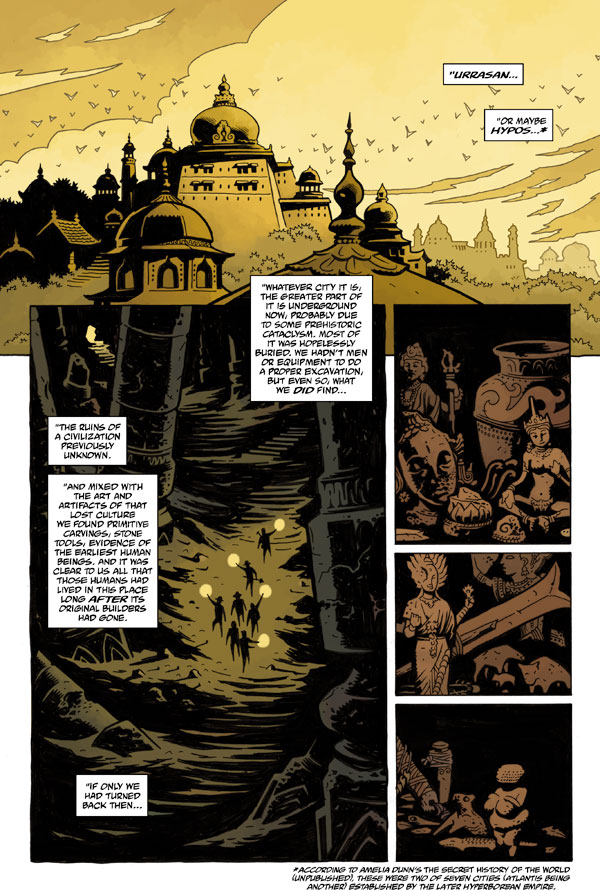

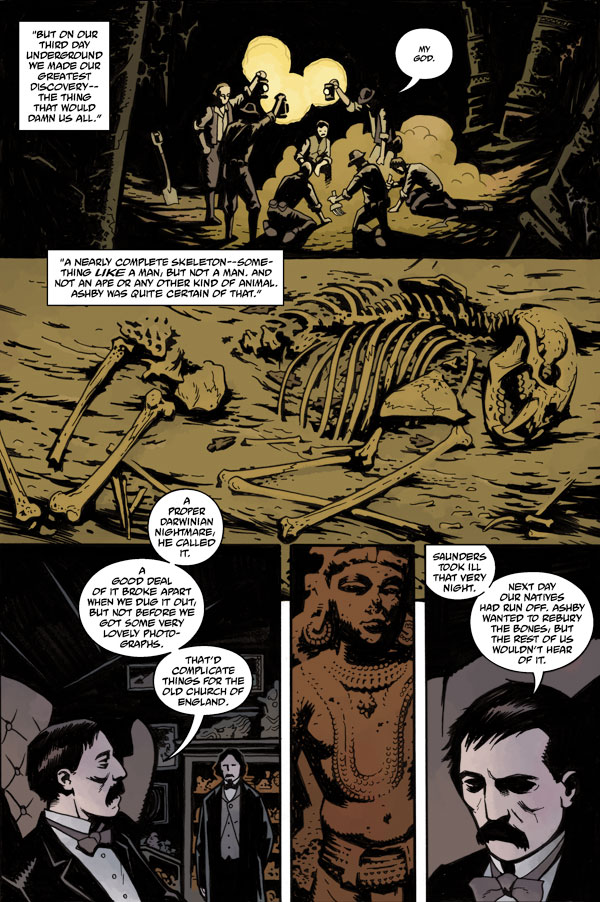

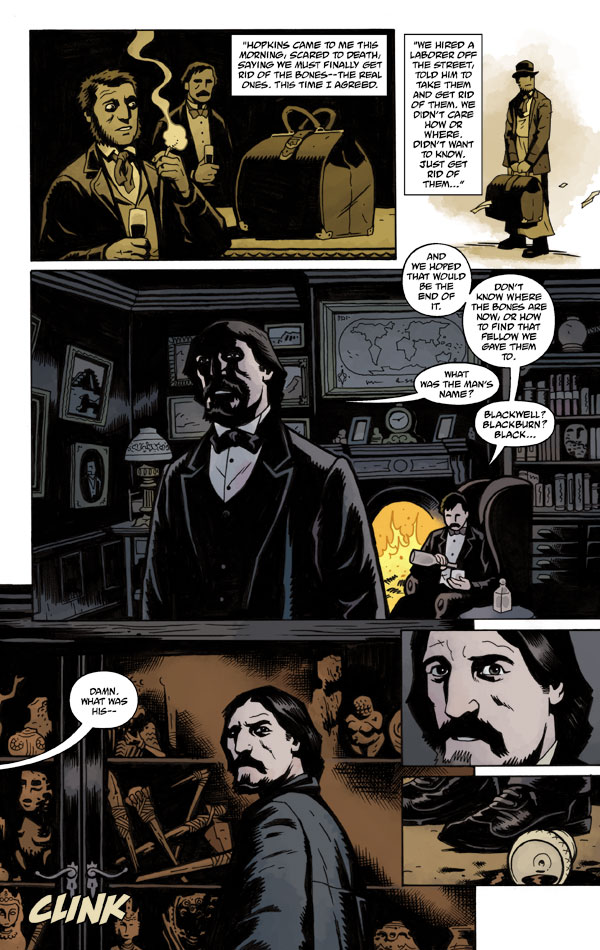

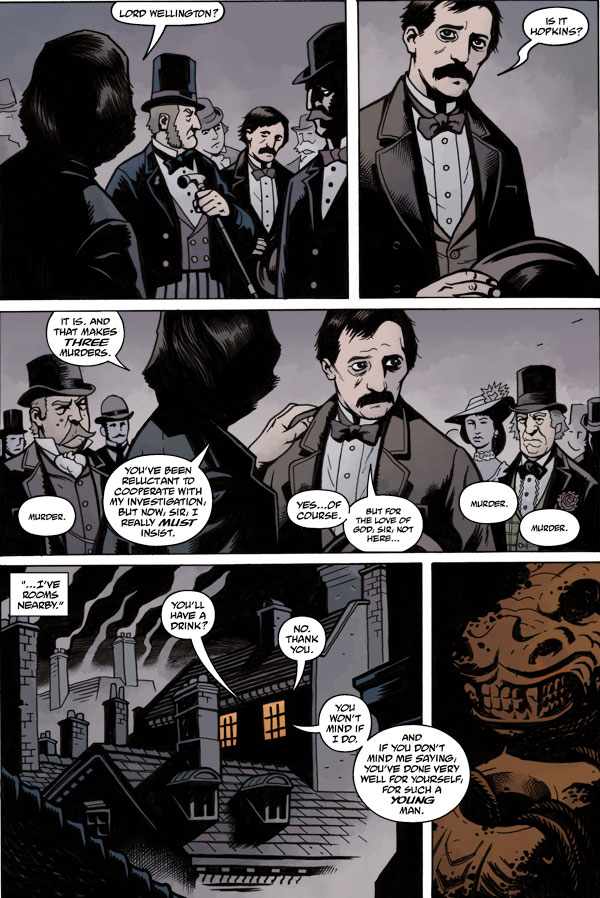

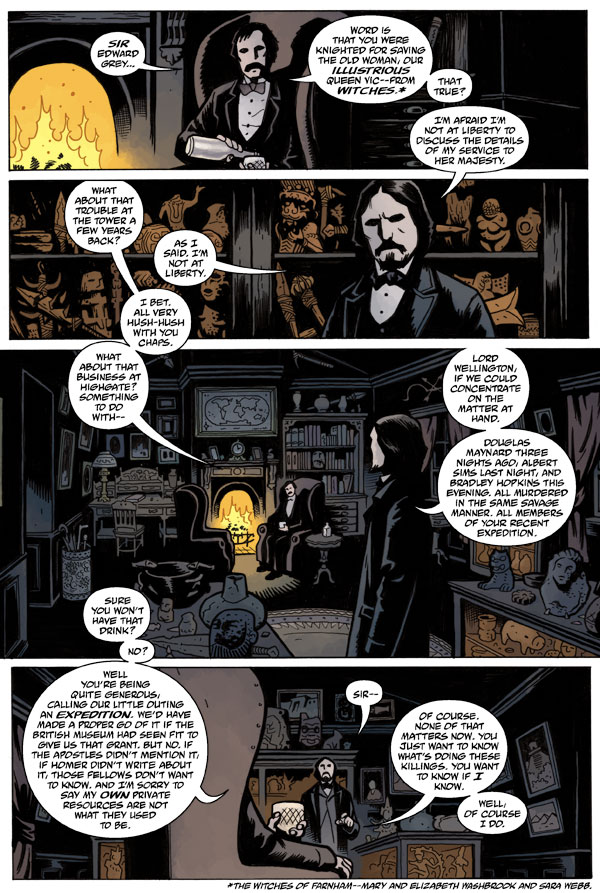

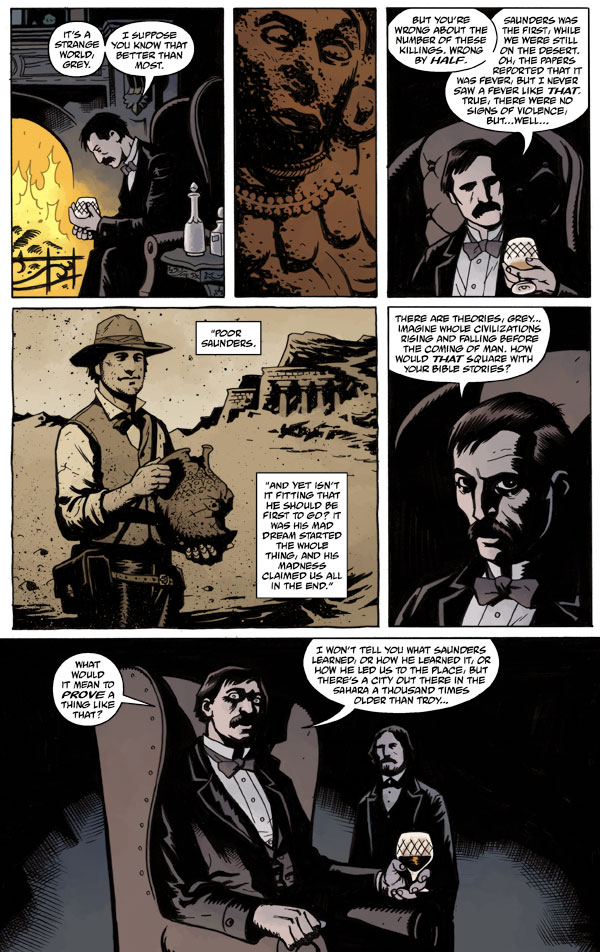

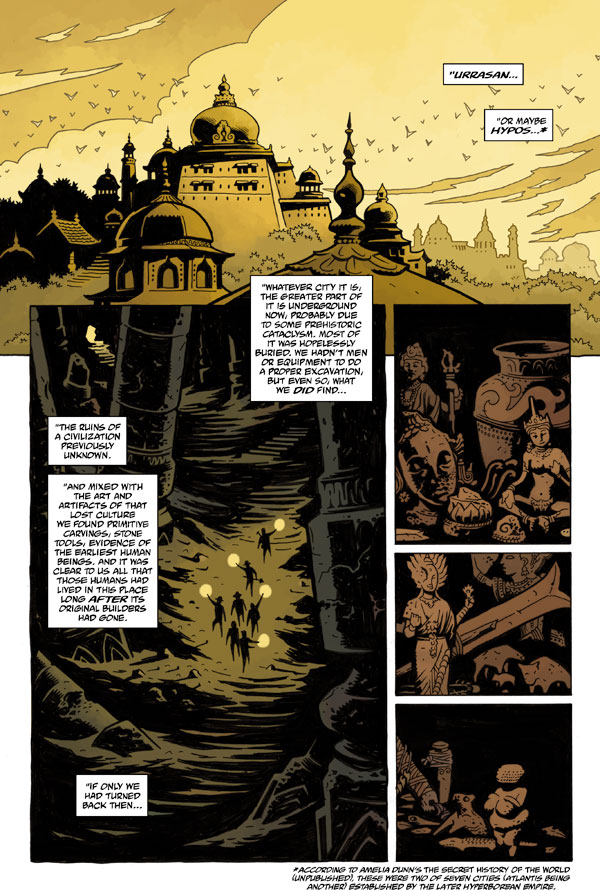

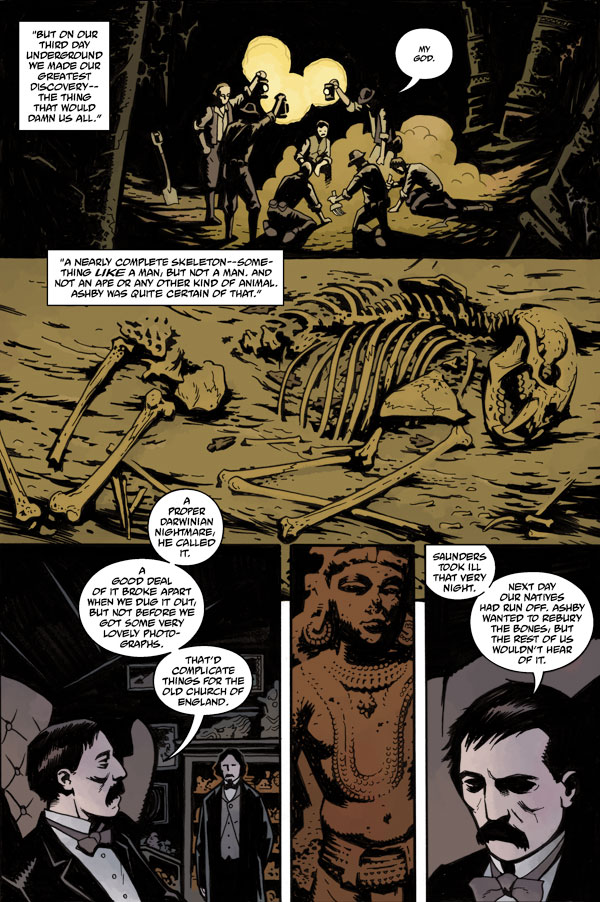

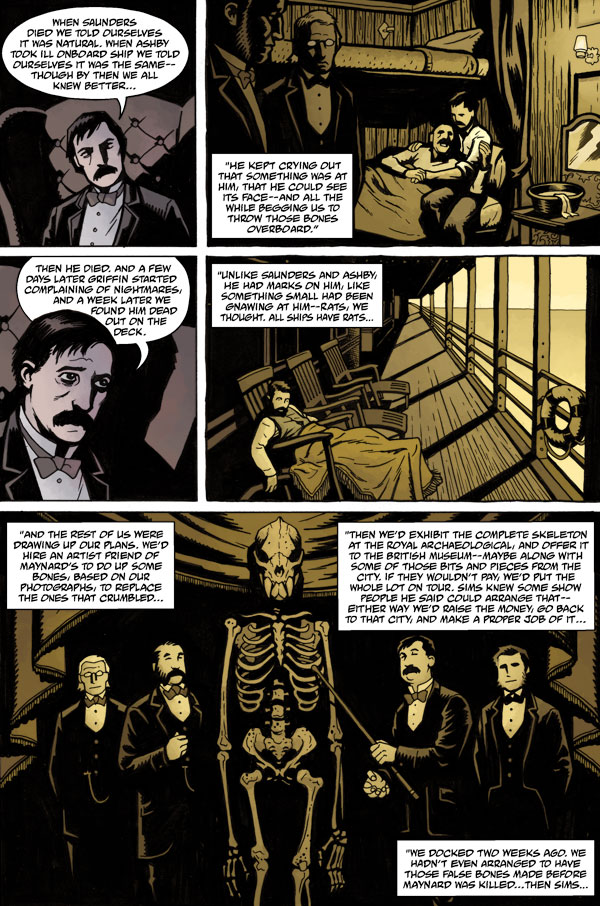

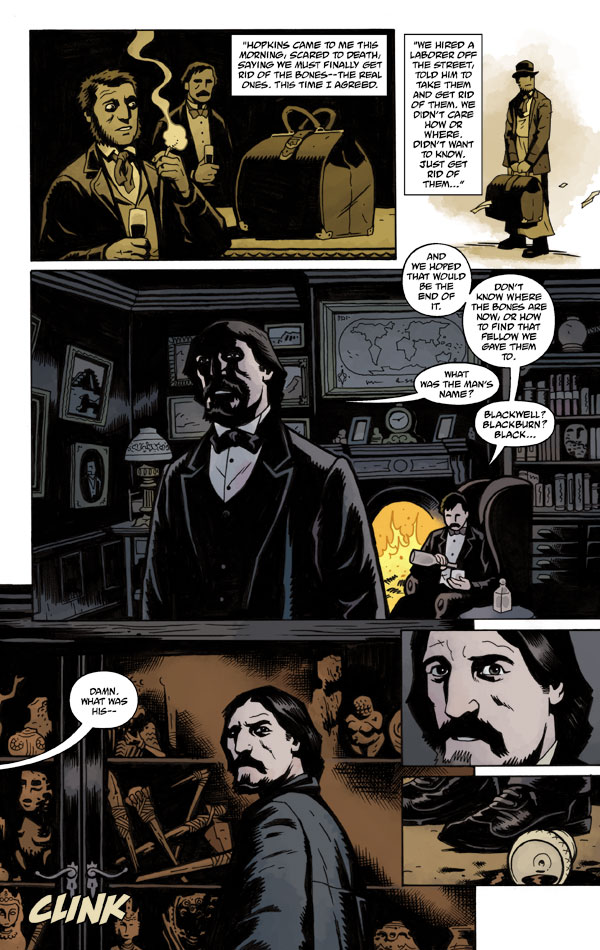

[Images: Preview spreads from Witchfinder: In the Service of Angels. Art by Ben Stenbeck, story by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics. If this gets you hooked, purchase the book].

[Images: Preview spreads from Witchfinder: In the Service of Angels. Art by Ben Stenbeck, story by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics. If this gets you hooked, purchase the book].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious about your work method, as far as nailing the details of these settings and landscapes. Do you travel a lot, watch a lot of movies, look at lots of photographs, talk to archaeologists—or it is really just an act of imagination?

Mignola: It’s a little bit of everything. I do watch a lot of films—which is great for getting the voice and the general character and the atmosphere—but I tend to come up with stories that are not super-specific to particular locations.

If I’m doing Victorian London, I’m not trying to do that story for a scholar of Victorian London. In a way, I say that this is more like a 1940s film version of London—in other words, I want to do at least the level of research that you’d see in an old Hollywood film. So I’ve given myself a little distance from reality with that.

But, as I say, I do like history. If I’m doing something specific, I’ve got a ton of reference books here in the studio, and I’ll try to make sure I get some of the names right and some of the dates right, if I’m referring to specific things. But, for the most part, I tend to shy away from plotting stories that are going to require a lot of very specific, historical research.

In Witchfinder, where I’m doing Whitechapel—well, I’ve been to Whitechapel. But I’m writing about 1880s, or maybe 1870s, Whitechapel, and I want it to seem like the real thing. So I did a little bit of homework on the East End. But the trouble with doing research for this stuff is that you start finding so much material that’s interesting, after you’ve already plotted the story, and you think, oh, I want to use this, and I want to use this, and I want to use this—well, uh oh, too late.

In terms of specifics, a little bit of dialogue, a little bit of color, a little bit of flavor, will give any story a certain amount of authenticity, but I’m not looking to make giant plot points out of that kind of stuff. It’s just background. Most of my buildings, and most of the things I do stories around—when I’m drawing these things, I’m trying to create objects, buildings, ships, whatever, with a particular background. I want it to feel like there is more to the story than can be told.

But, yes, you know, I have traveled a bit—and people love to think that what I’m doing comes from lots of traveling, and from talking to old monks and that sort of thing—

BLDGBLOG: [laughs]

Mignola: —and I have spent more time in Prague than I ever thought possible. But, other than a story I haven’t yet done—about a haunted couch—there are no experiences I’ve had that I’ve turned into stories. And the couch wasn’t haunted, you’ll be glad to hear; I think it was just infested with some kind of Eastern European insect.

For more exotic locations—like I did a story once set in Malaysia. It was entirely because I’d read a description years ago of a particular kind of Malaysian creature—a vampire—and I just knew I was going to do that story someday. But I needed pictures of Malaysia; I needed to do Malaysia research. That went back and forth for years, until, one day, I stumbled upon a book that just had really good photos of Malaysia. And that was it. It was the same with Norway: it was just a matter of some guy at a convention coming up to me with a book once that had great photos of Norway.

You know, I’m constantly looking for visual references. Story-wise, I’ve got all that stuff in my library—but I can never have enough photo references. There are still stories that are waiting to be told until I have the right references; and there are certain stories that I decided to set in a location just as an excuse for me to draw a particular place or building.

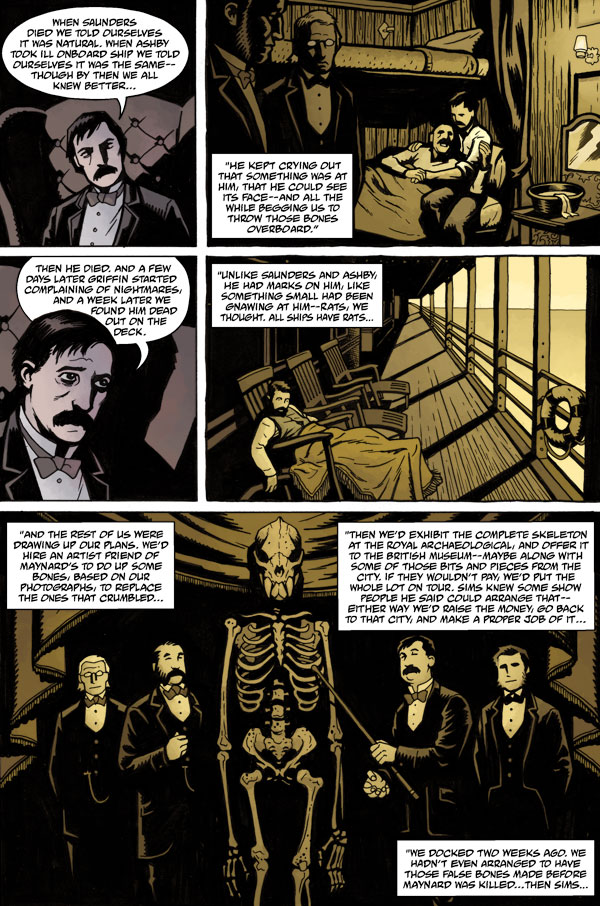

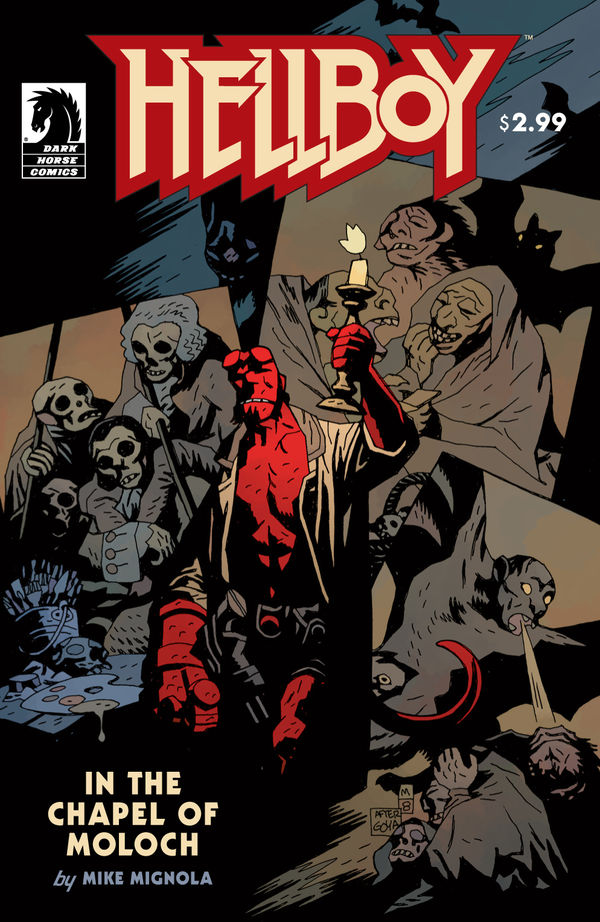

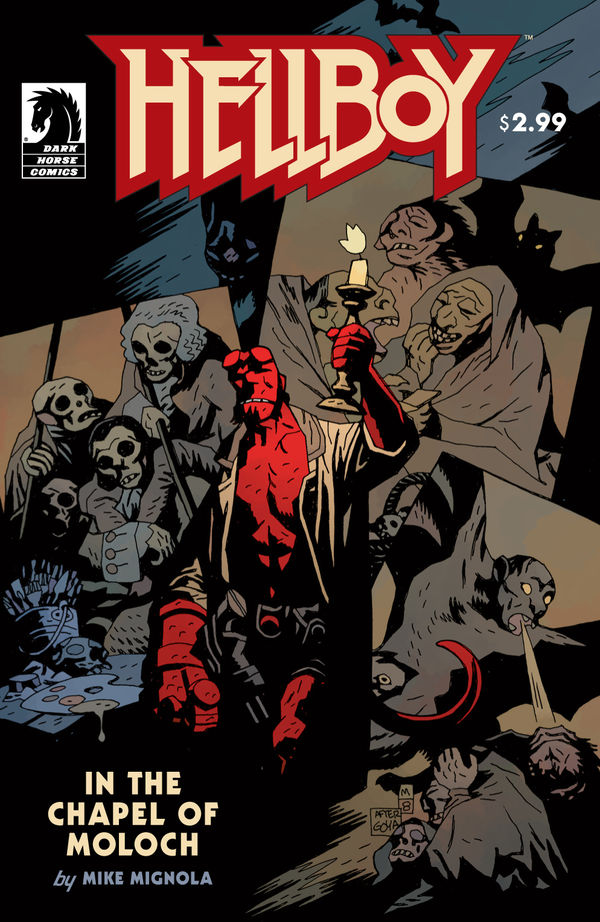

For instance, I did a story a couple of years ago called “In the Chapel of Moloch.” It was designed to take place almost entirely inside an old chapel. But the story wasn’t set in any particular location; it was just a matter of going to the books I had and looking for a building that would be fun to draw, or for a city that would be fun to draw, and I happened to have a book on Portugal. It had these great photos of decrepit hill towns, and a couple really good pictures of an old chapel. There was nothing about the story that was specific to Portugal—it was just that Portugal would be fun to draw. It was a nice, exotic location that I had never drawn before. And that’s usually how it works.

[Images: From Hellboy: In the Chapel of Moloch by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Images: From Hellboy: In the Chapel of Moloch by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: Stepping away from the idea of setting, I’m also interested in how you populate your stories with this constantly shifting catalog of sinister, yet natural, creatures: amphibians, frogs, worms, apes, gorillas. What is it about these particular species that works so well in terms of developing your mythological world?

Mignola: Well, I think monkeys are funny—that’s the easiest answer there. I don’t really love monkeys—but they’re kind of fun to draw. Something I always say is: monkeys always work. [laughter] People just like to see monkeys show up in these stories. I think it’s the absurdity of it.

In one of the first issues of Hellboy, I showed a 1940s scientist. I was drawing a bunch of scientists in a room, and one guy was actually just a severed head in a jar—but that wasn’t enough. The picture needed something else. So I drew a giant gorilla towering over them, with these Frankenstein-like bolts sticking out of his neck.

Oh—and you know what? Go back even earlier than that. Go back to one of the try-out stories—one of the teaser stories—before I even started the Hellboy series. It was a Frankenstein gorilla about to stick a needle in a girl’s neck—and, not that I stole the image from pulp magazines, but it’s such an old, clichéd, pulp magazine image. Making it a Frankenstein gorilla probably took it one step further, and made it my own, but it’s just… it’s funny. It’s so absurd it’s funny.

So, yeah, I use monkeys. And monkeys are usually the animal you associate with animal-testing. For instance, there’s another story where Hellboy’s blood is being extracted—and what are you going to inject Hellboy’s blood into? A rat? A rat just isn’t as much fun to draw turning into a giant hell-rat—actually, that’s not a bad idea—but it would be much more fun to take a monkey and turn it into a big demon-monkey, which is what I did.

As far as frogs and other amphibian stuff—that, again, is a reference to this kind of H.P. Lovecraft worldview where anything from the ocean is scary. Frogs, in a Lovecraft sense, are associated with some kind of unknowable world. They’re not from the ocean, but they’re also not from, you know, the woods. Where do they come from? And why are they always out there… chirping, or whatever the hell it is that frogs do? Lovecraft also uses birds that way—and birds are great—but I have a harder time drawing birds than frogs.

In the very first issue of Hellboy, I did a sequence with frogs in it, and it just sort of stuck. I established it early. Frogs will be my kind of icon characters; when frogs show up, you know something bad’s going to happen. They become symbolic of this kind of evil that’s always running around in the background.

And then things just tend to snowball. You know, you hear about something like a “rain of frogs,” which happens periodically for whatever reason—it’s one of those weird phenomena that gets written about—and, I thought, well, let me have a little bit of that kind of action. I mean, that’s a weird thing and it’s got a kind of authenticity to it: there’s something about it that’s unnatural, yet supposedly it does really happen. And I like that.

But I think you’ve put more thought into these questions than I have into why I do these things!

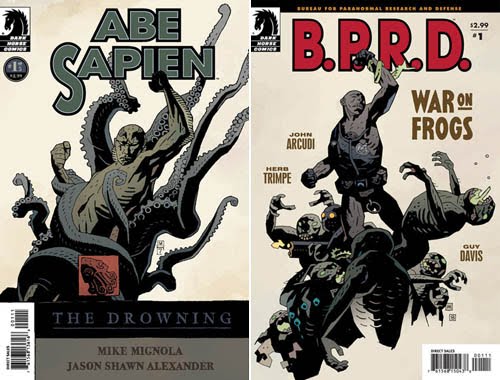

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Abe Sapien: The Drowning and B.P.R.D.: War on Frogs, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Abe Sapien: The Drowning and B.P.R.D.: War on Frogs, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: No, this is fascinating. It’s great to hear how you work. You mentioned H.P. Lovecraft: I’m curious to hear what you think it is about the Lovecraft universe—about the mythology of H.P. Lovecraft—that remains so appealing. In fact, it actually seems to be increasing in popularity today.

Mignola: For me, the monsters in Lovecraft are… you know, they’re fine. But what’s really appealing to me is his antiquarian sensibility. It’s the old houses in Rhode Island. It’s the fact that the guys are all scholars and they’re researching things, and there are references to different editions of this book or that book, and this edition is in that library, and a Latin translation of that book is in this other library. He writes about smart guys who spend a lot of time in libraries—and I love that.

His stories are set in a time when people are still wearing suits everyday. They even have upturned collars and things like that. There’s just a wonderfully old-fashioned, scholarly antiquarian feel to the stuff. It bridges the gap between modern horror and the old, classic M.R. James ghost stories—Lovecraft just added bigger monsters. Instead of some shadowy thing that skitters along the wall, it’s a giant octopus in space that makes people go crazy.

But it’s his obsession with old buildings, and shuttered windows, and climbing into church steeples—it’s his locations. I just love that.

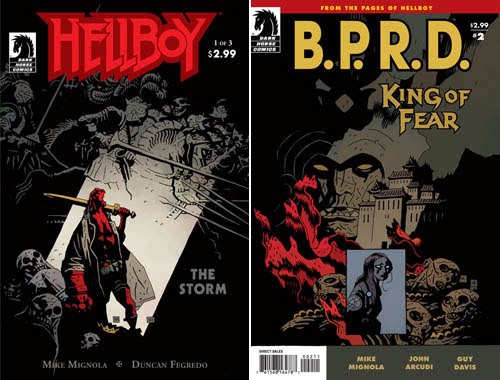

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Storm and B.P.R.D.: King of Fear, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Storm and B.P.R.D.: King of Fear, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: As well as things like abandoned fishing towns in New England, with collapsing wharves and moonlit salt marshes and that sort of thing.

Mignola: That’s actually one of my dream projects: to sit around and do half a dozen paintings of those towns. To do a series of drawings that’s just called Arkham, and it’s all about these buildings in creepy old coastal towns where the walls are falling over and they have these wonderful leans.

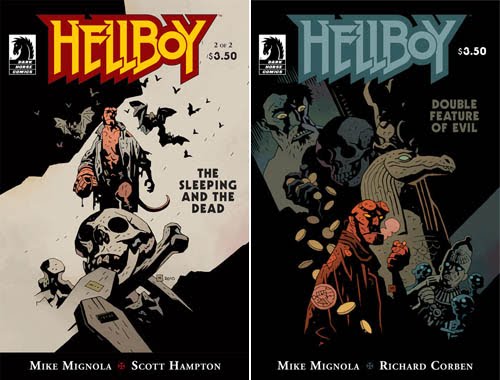

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Sleeping and the Dead and Hellboy: Double Feature of Evil, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

[Images: Covers by Mike Mignola, from Hellboy: The Sleeping and the Dead and Hellboy: Double Feature of Evil, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics].

BLDGBLOG: That brings us back to the idea of architecture and the role that architecture plays in your work. What brings you to draw a certain building or structure—and what do you add or exaggerate to make it more your own?

Mignola: [laughs] Well, once upon a time, when I started all this stuff, the one thing I didn’t want to draw at all was buildings. Because, growing up in California, buildings to me were an exercise in using a ruler and perspective, and shit like that. I just had no interest in drawing that kind of stuff.

It was only after having lived in New York for a while, around really old buildings—where you see that, actually, this building’s kind of sagging and that building’s kind of leaning against the other building next door and this chimney looks like, if those three wires weren’t there, it would all fall over, and that fire escape is at some odd angle—that’s when I really started to love architecture.

It’s one of those things that is still evolving in my work, as I become more and more comfortable drawing that sort of stuff: my buildings lean more.

Right now, I’m drawing an old house, and the house is leaning one way, the fence is leaning another way; I’m working from photo references, as I love to do, but I’m able to exaggerate it, and say, yeah, okay, this building’s kind of crooked in the photo, but let’s lean it way the hell over there. Let’s throw a couple of sticks out of it this way. Let’s make the building next door look like it’s about to fall over. And let’s make everything dark.

It’s really one of my favorite things to draw these days: old, crumbling architecture.

[Image: From “The Whittier Legacy” by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics; originally published in USA Today].

[Image: From “The Whittier Legacy” by Mike Mignola, courtesy of Dark Horse Comics; originally published in USA Today].

BLDGBLOG: Is there a particular building in your recent work that stands out this way?

Mignola: I recently did an 8-page story for USA Today called “The Whittier Legacy.” I said I was going to keep it simple for myself; I would set it almost entirely inside a house, in the dark. The way the story’s structured, we’re not going to spend a lot of time drawing furniture, little details, and things like that; it could just be an old, derelict house.

The most work that went into that story was going through my references and finding a really good house that would be fun to draw. I happened to have a book on Victorian houses that had a lot of really good texture to them and really nice angles, with things jutting out at weird angles. With the way I use shadow, it’s really important to me to have some sort of structure where things are going to be jutting out at different angles—because you can say, okay, if I light it on this side, that bit’s going to be in shadow; but if I light it on that side, then this is going to be in shadow. A square? You get light on one side and black on the other.

But if it’s a square with other things sort of jutting at you out of the shadows, and if you put a big porch on it, and, you know, it’s a derelict place so it’s all sort of sagging the way those old places start to do—then that’s a really good day for me, being able to draw stuff like that.

• • •Thanks to

Mike Mignola for taking the time to talk—and for producing so many awesome comics. Thanks, as well, to Jim Gibbons, Jeremy Atkins, and Scott Allie at

Dark Horse Comics for their help with the images. If this interview piques your interest, consider picking up some of

Mignola’s work for yourself.

[Image: “The Empty Quarter (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Image: “The Empty Quarter (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.] [Image: “Groundwater Grids (North Dakota)” (2020), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Image: “Groundwater Grids (North Dakota)” (2020), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Images: “Keys II (Florida)” (2020) and “Keys I (Florida)” (2020), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; the source maps for these are particularly interesting, because they utilize satellite photography.]

[Images: “Keys II (Florida)” (2020) and “Keys I (Florida)” (2020), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; the source maps for these are particularly interesting, because they utilize satellite photography.]

[Images: “Morse Landscape II (Louisiana)” and “Morse Landscape I (Louisiana)” (2021), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Images: “Morse Landscape II (Louisiana)” and “Morse Landscape I (Louisiana)” (2021), collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Images: Various collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.]

[Images: Various collages by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.] [Image: “Terrestrial Astronomy (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; it’s a pedestrian observation, but inverting the color scheme of geological maps makes them look like maps of stars.]

[Image: “Terrestrial Astronomy (Nevada)” (2021), collage by Geoff Manaugh, using maps from the U.S. Geological Survey; it’s a pedestrian observation, but inverting the color scheme of geological maps makes them look like maps of stars.]

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the  [Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the

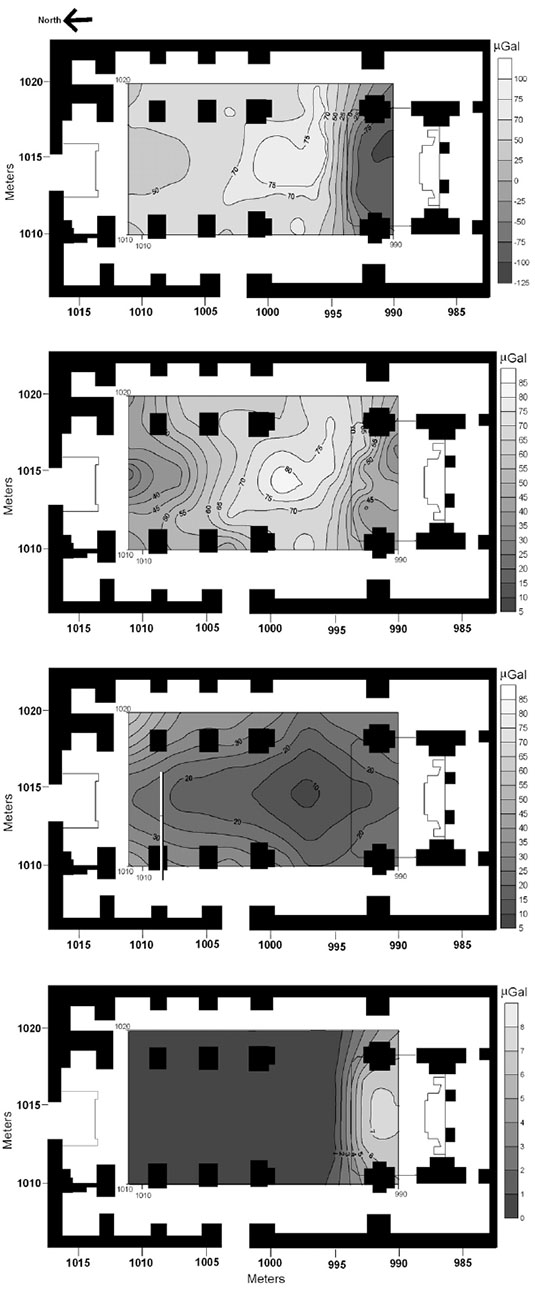

[Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the  [Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the

[Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the  [Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the

[Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the

[Image: From a cover by

[Image: From a cover by  [Image: A cover by

[Image: A cover by  [Images: (left) A cover from

[Images: (left) A cover from  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: Preview spreads from

[Images: Preview spreads from

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by  [Images: Covers by

[Images: Covers by  [Image: From “

[Image: From “