[Image: Many Norths: Building in a Shifting Territory].

[Image: Many Norths: Building in a Shifting Territory].

Architects Lola Sheppard and Mason White of Lateral Office have a new book out, Many Norths: Building in a Shifting Territory, published by Actar.

The book is something of a magnum opus for the office, compiling many years’ worth of research—architectural, infrastructural, geopolitical—including original interviews, maps, diagrams, and historical analyses of the Canadian North. Or the Canadian Norths, as Sheppard and White make clear.

[Image: A spread from the book, featuring a slightly different, unused layout; via Actar].

[Image: A spread from the book, featuring a slightly different, unused layout; via Actar].

The plural nature of this remote territory is the book’s primary emphasis—that no one model or description fits despite superficial resemblances, whether they be economic, ecological, climatic, or even military, across massive geographic areas.

“For better or for worse,” they write in the book’s opening chapter, “if nothing else [the Norths are] a shifting, multivalent territory: culturally dynamic, environmentally changing, and socially evolving. Digital and physical mobility networks expand, ground conditions change, treelines shift, species hybridize, and cultures remain dynamic and cross-pollinating.”

Exploring these differences, they add, was “the motivation for this book.”

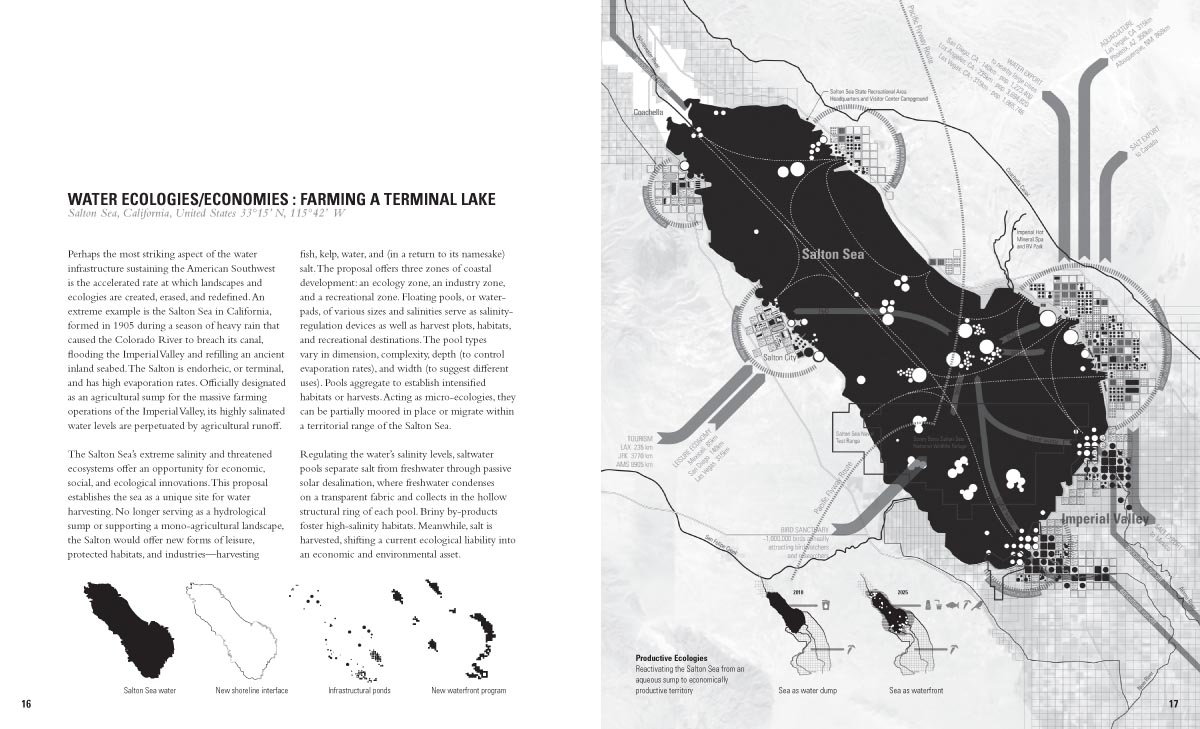

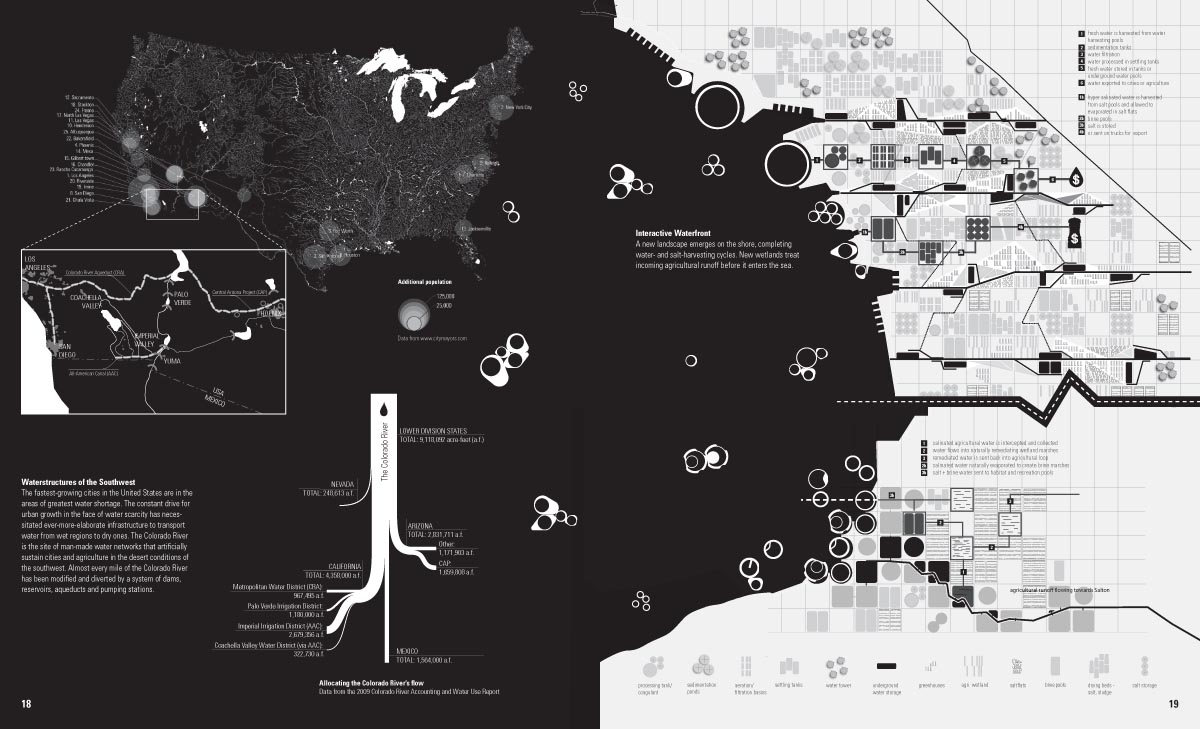

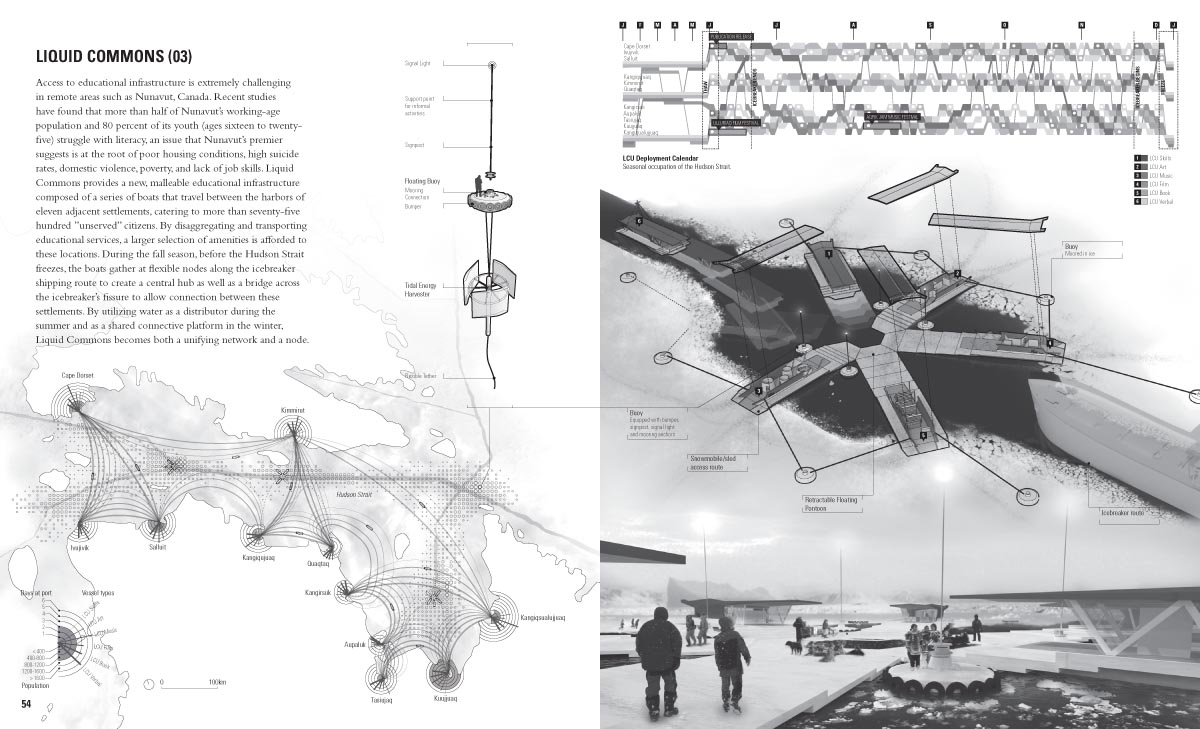

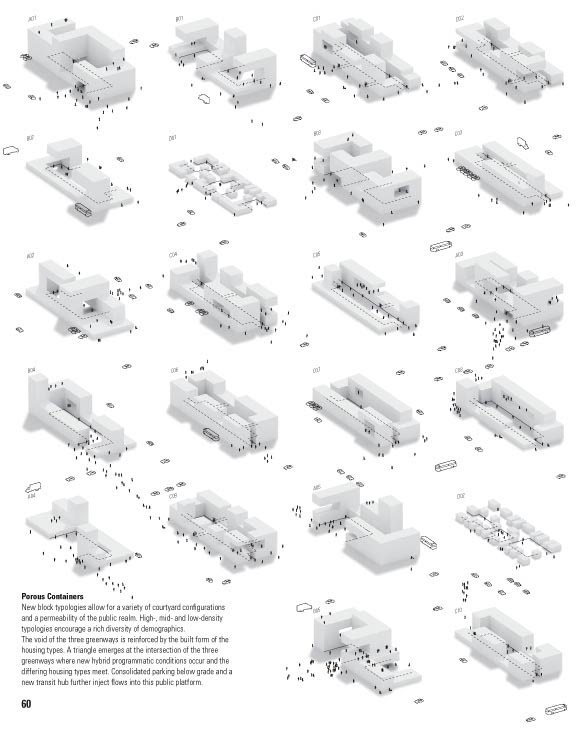

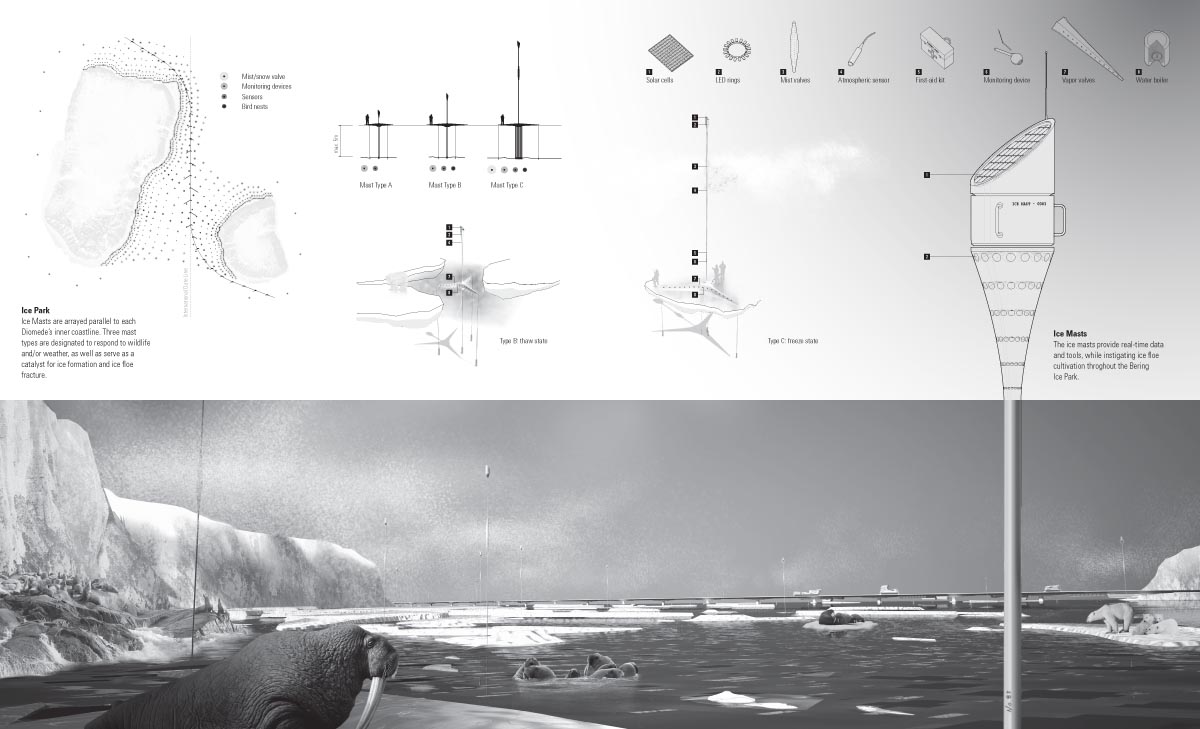

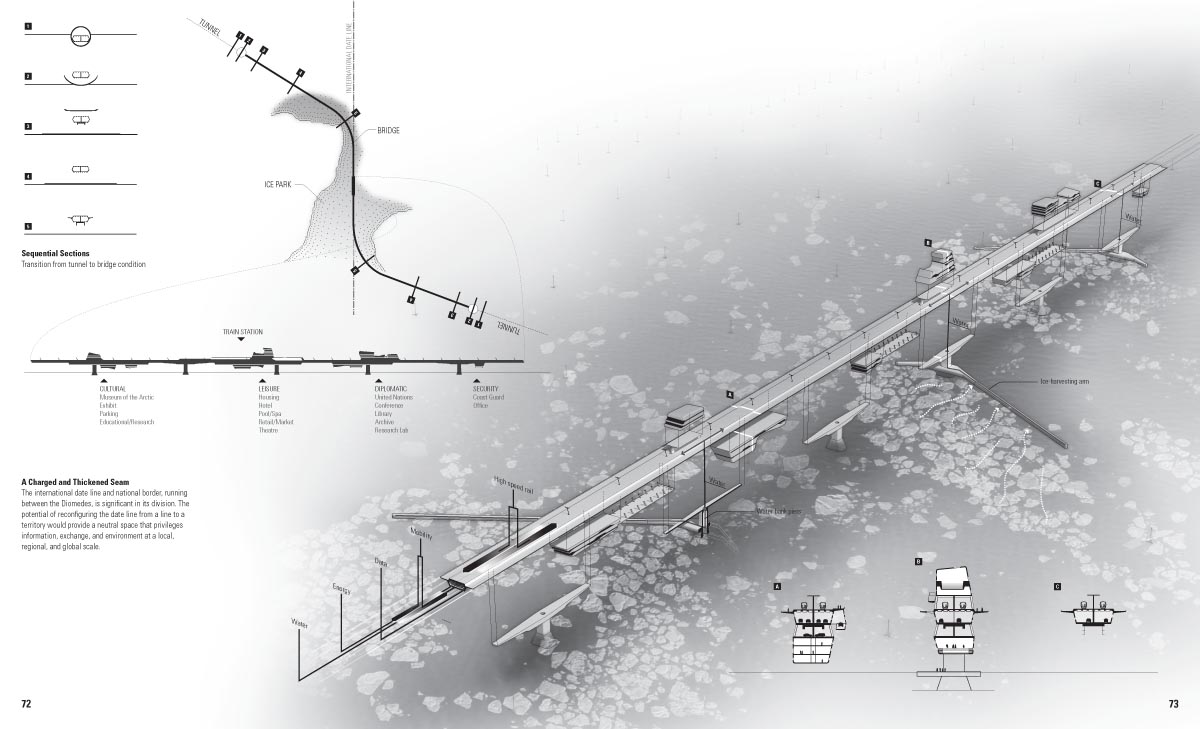

[Images: Spreads from Many Norths].

[Images: Spreads from Many Norths].

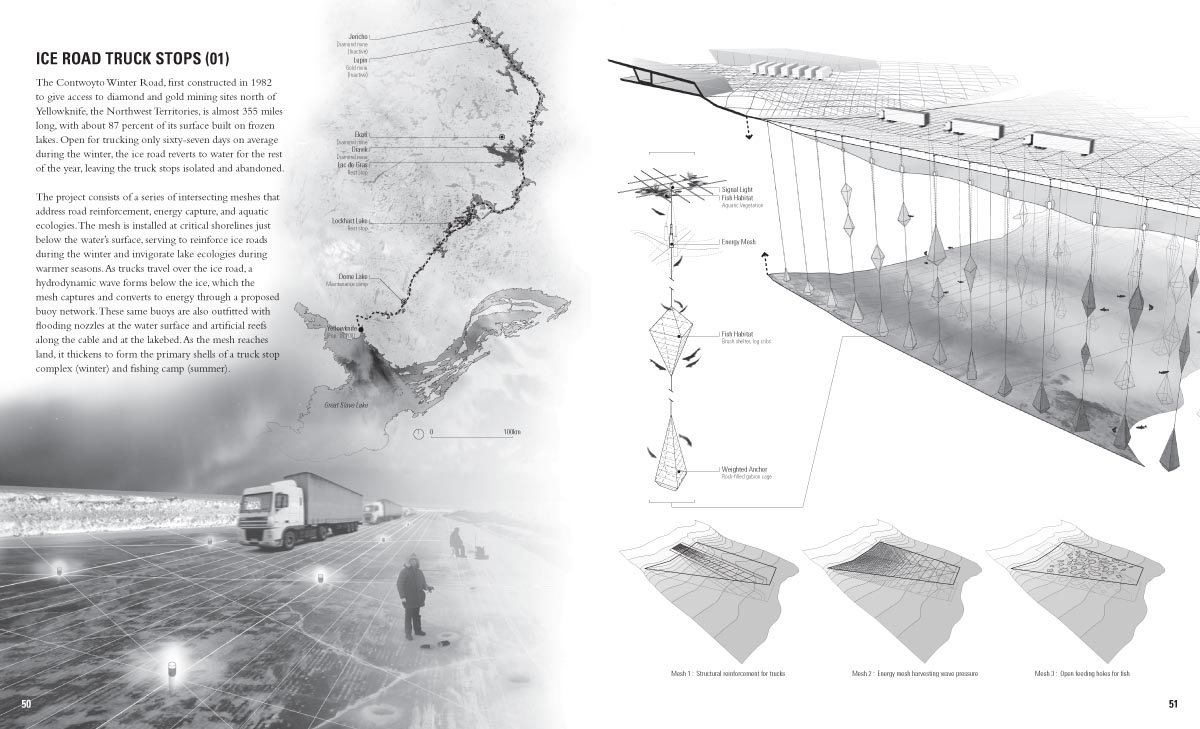

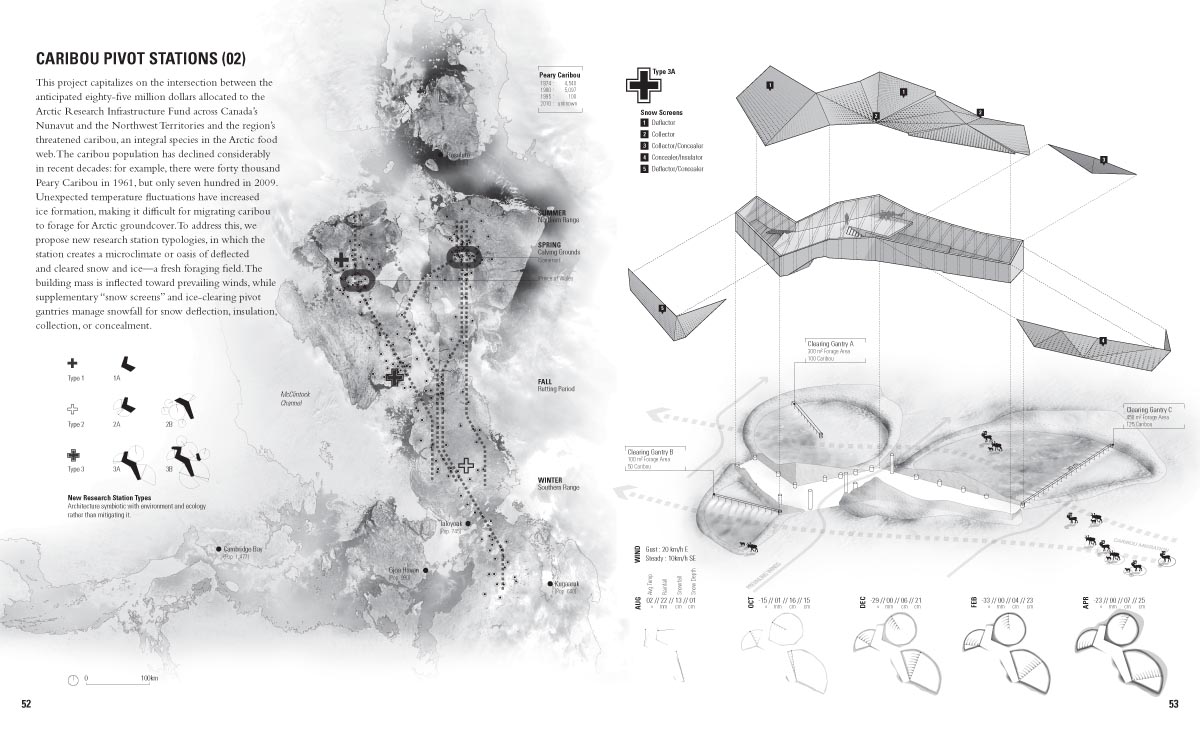

Their secondary point, however, is that this sprawling, multidimensional region of shifting ground planes and emergent resource wealth is now the site of “a distinct northern vernacular,” or “polar vernacular,” a still-developing architectural language that the book also exhaustively documents, from adjustable foundation piles to passive ventilation.

There are Mars simulations, remote scientific facilities, schools, military bases, temporary snowmobile routes (snowmobile psychogeography!), and communal utilities corridors.

[Images: Spreads from Many Norths].

[Images: Spreads from Many Norths].

The book is cleanly designed, but its strength is not in its visual impact; it’s in how it combines rigorous primary research with architectural documentation.

The interviews are a particular highlight.

Among more than a dozen other subjects, there are discussions with anthropologist Claudio Aporto on “wayfinding techniques and spatial perception” among the Inuit, with “master mariner” Thomas Paterson on the logistics of Arctic shipping, with historian Shelagh Grant on “sovereignty” and “security” in the far north, and with Baffin Island native whale hunter Charlie Qumuatuq on seasonal food webs.

[Images: Spreads from Many Norths].

[Images: Spreads from Many Norths].

While the focus of Many Norths is, of course, specifically Canadian, its topics are relevant not only to other Arctic nations but to other extreme environments and remote territories.

In fact, the book serves as a challenging precedent for similar undertakings—one can easily imagine a Many Wests, for example, documenting various modes of inhabiting the American Southwest, with implications for desert regions all over the world.

[Image: Spread from Many Norths].

[Image: Spread from Many Norths].

In any case, I’ve long been a fan of Lateral Office’s work and was thrilled to see this come out.

For those of you already familiar with Lateral’s earlier design propositions published in their Pamphlet Architecture installment, Coupling, Many Norths can be seen as an archive of directly relevant supporting materials. The two books thus make a useful pair, exemplifying the value of developing a deep research archive while simultaneously experimenting with those materials’ speculative design applications.

(Thanks to Mason White for sending me a copy of the book. Vaguely related: Landscape Futures and Landscape Futures Arrives).

[Image: Fermont’s weather-controlling residential super-wall, courtesy

[Image: Fermont’s weather-controlling residential super-wall, courtesy  [Image: Wind-shadow studies, Fermont; courtesy

[Image: Wind-shadow studies, Fermont; courtesy  [Image: Fermont and its iron mine, as seen on

[Image: Fermont and its iron mine, as seen on  [Image: Fermont apartments, design sketch, courtesy

[Image: Fermont apartments, design sketch, courtesy  [Image: Constructing Fermont, courtesy

[Image: Constructing Fermont, courtesy

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From