[Image: Flying with the LAPD Air Support Division; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Flying with the LAPD Air Support Division; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

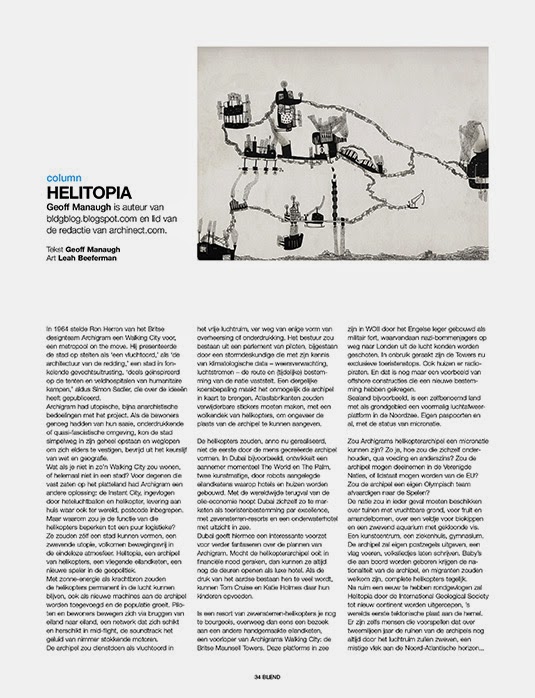

Over the past three years, I’ve gone on multiple flights with the LAPD Air Support Division, during both the day and night; my goal was to understand how police see the city from above.

[Image: Freeways and escape routes; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Freeways and escape routes; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

Does the aerial view afford new insights into how distant neighborhoods are connected, for example, or how criminals might attempt to hide—or flee—from police oversight? Where are these other, illicit routes and refuges?

More importantly, are they temporary accidents of criminal behavior and urban geography, or are they much deeper flaws and vulnerabilities hidden in the city’s very design?

[Images: Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

Aerial patrols seems to promise a ubiquitous, and near-omniscient, amplification of police vision, even as the fabric of the city itself is put to alternative use by the activities of criminals.

I documented these flights through hundreds of photographs—many of which can be seen here—as well as in my forthcoming book, A Burglar’s Guide to the City.

However, an excerpt of that book has also been adapted for this weekend’s New York Times Magazine, including a look at Thomas More’s Utopia in the context of the LAPD, the navigational “rules of four,” and a look at the array of technical devices installed aboard each police helicopter.

[Images: Inside the airship; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Inside the airship; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

The “rules of four,” for example, as I write in the piece, are “guidelines [that] fall somewhere between a rule of thumb and an algorithm, and they allow for nearly instantaneous yet accurate aerial navigation.”

“The way the parcels work in the city of Los Angeles,” [LAPD Chief Tactical Flight Officer Cole Burdette explained to me], “is that Main Street and First Street are the hub of the city.” The street numbers radiate outward — by quadrant, east, west, north, south — with blocks advancing by hundreds (the 3800 block below 38th Street) and building numbers advancing by fours (3804, 3808, 3812, etc.). The rest is arithmetic.

(…)

With the rules of four, an otherwise intimidating and uncontrollable knot of streets takes on newfound clarity. It is no coincidence that the Los Angeles Police Department built its main headquarters at the center of it all, at the intersection of First and Main. It placed the department at the numerological heart of the metropolis, the zero point from which everything else emanates.

What fascinates me through all of this is how the city can be used as a tool of police authority, a seemingly endless crystalline grid of numbers and addresses continually re-scanned from above by helicopter—

[Image: Watchers; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Watchers; photo by BLDGBLOG].

—yet, at the same time, the city can also be manipulated from below, against those same figures of aerial power, becoming an instrument of criminal evasion and spatial camouflage.

[Image: Night flight across the grid; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Night flight across the grid; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

The very notion of the “getaway route” is revealing here for what it implies about a city’s secondary use as a means of escape, offering hidden lines of flight from figures of authority.

In the book, I explore this a bit more through, among other things, the work of Grégoire Chamayou, including his research into the history of manhunts and his brief look at the speculative re-design of Paris as a kind of immersive police catalog in which “every move will be recorded.”

[Image: Over Porter Ranch and the San Fernando Valley; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Over Porter Ranch and the San Fernando Valley; photos by BLDGBLOG].

Paris, Chamayou writes, “was to be divided into distinct districts, each receiving a letter, and each being subdivided into smaller sub-districts.”

In each sub-district each street had accordingly to receive a specific name. On each street, each house had to receive a number, engraved on the front house—which was not the case at the time. Each floor of each building was also to have a number engraved on the wall. On each floor, each door should be identified with a letter. Every horse car should also bear a number plate. In short, the whole city was to be reorganized according to the principles of a rationalized addressing system.

In that context, the Air Support Division’s “rules of four” as a police-navigation strategy take on a particularly interesting nuance—as do hypothetical means of resistance to police power through the deliberate complication of local addressing systems.

[Images: Moving maps and binoculars over L.A.; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Moving maps and binoculars over L.A.; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

The book excerpt in the Times also briefly picks up on some themes elaborated in an article I wrote for Cabinet Magazine a few years ago, discussing how the infrastructure of Los Angeles itself inadvertently permits certain classes of criminal activity.

[Image: Night flying; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Night flying; photo by BLDGBLOG].

The most obvious example of this unintended side-effect of transportation planning is the so-called “stop-and-rob.” From The New York Times Magazine:

The construction of the city’s freeway system in the 1960s helped to instigate a later spike in bank-crime activity by offering easy getaways from financial institutions constructed at the confluence of on-ramps and offramps. This is a convenient location for busy commuters—but also for prospective bandits, who can pull off the freeway, rob a bank and get back on the freeway practically before the police have been alerted. The maneuver became so common in the 1990s that the Los Angeles police have a name for it: a “stop-and-rob.”

In any case, the book obviously elaborates on these themes in much greater length—and it comes out next week, so please consider pre-ordering a copy—but The New York Times Magazine excerpt is a great place to start.

[Image: Somewhere over the San Fernando Valley; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Somewhere over the San Fernando Valley; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

Meanwhile, if you yourself are planning any illicit activities, as an added bonus the article includes insights from Air Support Division pilots and tactical flight officers on the limitations of their own surveillance techniques, such as how the streets around Los Angeles International Airport have become a popular hiding spot for criminals fleeing police helicopters by car and some especially unlikely tactics used to evade thermal detection by the LAPD’s Forward-Looking Infrared or FLIR cameras.

When in doubt—although this is not mentioned in the article—drive into the fog, where the helicopters can’t follow you.

[Image: Urban horizon lines; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Urban horizon lines; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

For now, here are a bunch of photos, including many Instagrams, taken from July 2013 to March 2016, including night flights in January 2014 and March 2016—

[Images: Night from above; photos & Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Night from above; photos & Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

—as well as day and early evening flights taken in July 2013 and March 2016.

[Images: Note the shot of Watts Towers; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Note the shot of Watts Towers; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

Finally, a chunk of non-Instagram shots, in case those colored filters are making your eyes cross over.

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG, many featuring a home barricade call in Pacoima].

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG, many featuring a home barricade call in Pacoima].

Check out the article—and let me know what you think of the book, once it’s published.

[Image: Sunset approaching downtown L.A.; cropped Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Sunset approaching downtown L.A.; cropped Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Test-crash from “California Freeways: Planning For Progress,” courtesy Prelinger Archives].

[Image: Test-crash from “California Freeways: Planning For Progress,” courtesy Prelinger Archives]. [Image: From Another Science Fiction, via Wired].

[Image: From Another Science Fiction, via Wired]. [Image: Thomas More’s

[Image: Thomas More’s  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Early type experiment for “

[Image: Early type experiment for “ [Image: Thomas More’s

[Image: Thomas More’s  [Image: Flying with the LAPD Air Support Division; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Flying with the LAPD Air Support Division; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Freeways and escape routes; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Freeways and escape routes; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Inside the airship; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Inside the airship; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Watchers; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Watchers; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Night flight across the grid; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Night flight across the grid; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Over Porter Ranch and the San Fernando Valley; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Over Porter Ranch and the San Fernando Valley; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Moving maps and binoculars over L.A.; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Moving maps and binoculars over L.A.; Instagrams by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Night flying; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Night flying; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Somewhere over the San Fernando Valley; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Somewhere over the San Fernando Valley; Instagram by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Urban horizon lines; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Urban horizon lines; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Night from above; photos & Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Night from above; photos & Instagrams by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Note the shot of

[Images: Note the shot of

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG, many featuring a home barricade call in Pacoima].

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG, many featuring a home barricade call in Pacoima]. [Image: Sunset approaching downtown L.A.; cropped Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Sunset approaching downtown L.A.; cropped Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via  [Image: The complete front/back cover for

[Image: The complete front/back cover for  [Image: Flying with the LAPD Air Support Division; Instagram by

[Image: Flying with the LAPD Air Support Division; Instagram by

[Image:

[Image: