[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

(This post originally published on Venue).

Fort Irwin is a U.S. army base nearly the size of Rhode Island, located in the Mojave Desert about an hour’s drive northeast of Barstow, California. There you will find the National Training Center, or NTC, at which all U.S. troops, from all services, spend a twenty-one day rotation before they deploy overseas.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

Sprawling and often infernally hot in the summer months, the base offers free tours, open to the public, twice a month. Venue—BLDGBLOG’s ongoing collaboration with Edible Geography’s Nicola Twilley, supported by the Nevada Museum of Art‘s Center for Art + Environment—made the trip, cameras in hand and notebooks at the ready, to learn more about the simulated battlefields in which imaginary conflicts loop, day after day, without end.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

Coincidentally, as we explored the Painted Rocks located just outside the gate while waiting for the tour to start, an old acquaintance from Los Angeles—architect and geographer Rick Miller—pulled up in his Prius, also early for the same tour.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

We laughed, said hello, and caught up about a class Rick had been teaching at UCLA about the military defense of L.A. during World War II, through to the present. An artificial battlefield, beyond even the furthest fringes of Los Angeles, Fort Irwin thus seemed like an appropriate place to meet.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

We were soon joined by a small group of other visitors—consisting, for the most part, of family members of soldiers deployed on the base, as well as two architecture students from Montréal—before a large white tour bus rolled up across the gravel.

Renita, a former combat videographer who now handles public affairs at Fort Irwin, took our names, IDs, and signatures for reasons of liability (we would be seeing live explosions and simulated gunfire, and there was always the risk that someone might get hurt).

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

The day began with a glimpse into the economics and culture of how a nation prepares its soldiers for war; an orientation, of sorts, before we headed out to visit one of fifteen artificial cities scattered throughout the base.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

In the plush lecture hall used for “After Action Reviews”—and thus, Renita apologized, air-conditioned to a morgue-like chill in order to keep soldiers awake as their adrenalin levels crash—we received a briefing from the base’s commander, Brigadier General Terry Ferrell.

With pride, Ferrell noted that Fort Irwin is the only place where the U.S. military can train using all of the systems it will later use in theater. The base’s 1,000 square miles of desert is large enough to allow what Ferrell called “great maneuverability”; its airspace is restricted; and its truly remote location ensures an uncluttered electromagnetic spectrum, meaning that troops can practice both collection and jamming. These latter techniques even include interfering with GPS, providing they warn the Federal Aviation Administration in advance.

Oddly, it’s worth noting that Fort Irwin also houses the electromagnetically sensitive Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, part of NASA’s global Deep Space Network. As science writer Oliver Morton explains in a paper called “Moonshine and Glue: A Thirteen-Unit Guide to the Extreme Edge of Astrophysics” (PDF), “when digitized battalions slug it out with all the tools of modern warfare, radio, radar, and electronic warfare emissions fly as freely around Fort Irwin as bullets in a battle. For people listening to signals from distant spacecraft on pre-arranged frequency bands, this noise is not too much of a problem.” However, he adds, for other, far more sensitive experiments, “radio interference from the military next door is its biggest headache.”

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

Unusually for the American West, where mineral rights are often transferred separately, the military also owns the ground beneath Fort Irwin, which means that they have carved out an extensive network of tunnels and caves from which to flush pretend insurgents.

This 120-person strong insurgent troop is drawn from the base’s own Blackhorse Regiment, a division of the U.S. Army that exists solely to provide opposition. Whatever the war, the 11th Armored is always the pretend enemy. According to Ferrell, their current role as Afghan rebels is widely envied: they receive specialized training (for example, in building IEDs) and are held to “reduced grooming standards,” while their mission is simply to “stay alive and wreak havoc.”

If they die during a NTC simulation, they have to shave and go back on detail on the base, Ferrell added, so the incentive to evade their American opponents is strong.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

In addition to the in-house enemy regiment, there is an entire 2,200-person logistics corps dedicated to rotating units in and out of Fort Irwin and equipping them for training. Every ordnance the United States military has, with the exception of biological and chemical weapons, is used during NTC simulations, Ferrell told us. What’s more, in the interests of realism (and expense be damned), troops train using their own equipment, which means that bringing in, for example, the 10th Mountain Division (on rotation during our visit), also means transporting their tanks and helicopters from their home base at Fort Drum, New York, to California, and back again.

Units are deployed to Fort Irwin for twenty-one days, fourteen of which are spent in what Fort Irwin refers to as “The Box” (as in “sandbox”). This is the vast desert training area that includes fifteen simulated towns and the previously mentioned tunnel and caves, as well as expansive gunnery ranges and tank battle arenas.

Following our briefing, we headed out to the largest mock village in the complex, the Afghan town of Ertebat Shar, originally known, during its Iraqi incarnation, as Medina Wasl. Before we re-boarded the bus, Renita issued a stern warning: “‘Afghanistan’ is not modernized with plumbing. There are Porta-Johns, but I wanted to let you know the situation before we roll out there.”

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

A twenty-minute drive later, through relatively featureless desert, our visit to “Afghanistan” began with a casual walk down the main street, where we were greeted by actors trying to sell us plastic loaves of bread and piles of fake meat. Fort Irwin employs more than 350 civilian role-players, many of whom are of Middle Eastern origin, although Ferrell explained that they are still trying to recruit more Afghans, in order “to provide the texture of the culture.”

The atmosphere is strangely good-natured, which was at least partially amplified by a feeling of mild embarrassment, as the rules of engagement, so to speak, are not immediately clear; you, the visitor, are obviously aware of the fact that these people are paid actors, but it feels distinctly odd to slip into character yourself and pretend that you might want to buy some bread.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

In fact, it’s impossible not to wonder how peculiar it must be for a refugee, or even a second-generation immigrant, from Iraq or Afghanistan, to pretend to be a baker in a simulated “native” village on a military base in the California desert, only to see tourists in shorts and sunglasses walking through, smiling uncomfortably and taking photos with their phones before strolling away without saying anything.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

Even more peculiarly, as we reached the end of the street, the market—and all the actors in it—vanished behind us, dispersing back into the fake city, as if only called into being by our presence.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

By now, with the opening act over, we were stopped in front of the town’s “Lyndon Marcus International Hotel” to take stock of our surroundings. In his earlier briefing, Ferrell had described the simulated villages’ close attention to detail—apparently, the footprint for the village came from actual satellite imagery of Baghdad, in order to accurately recreate street widths, and the step sizes inside buildings are Iraqi, rather than U.S., standard.

Dimensions notwithstanding, however, this is a city of cargo containers, their Orientalized facades slapped up and plastered on like make-up. Seen from above, the wooden frames of the illusion become visible and it becomes more and more clear that you are on a film set, an immersive theater of war.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

This kind of test village has a long history in U.S. war planning. As journalist Tom Vanderbilt writes in his book Survival City, “In March 1943, with bombing attacks on cities being intensified by all sides, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction at Dugway [Utah] on a series of ‘enemy villages,’ detailed reproductions of the typical housing found in the industrial districts of cities in Germany and Japan.”

The point of the villages at Dugway, however, was not to train soldiers in urban warfare—with, for instance, simulated street battles or house-to-house clearances —but simply to test the burn capacity of the structures themselves. What sorts of explosives should the U.S. use? How much damage would result? The attention to architectural detail was simply a subset of this larger, more violent inquiry. As Vanderbilt explains, bombs at Dugway “were tested as to their effectiveness against architecture: How well the bombs penetrated the roofs of buildings (without penetrating too far), where they lodged in the building, and the intensity of the resulting fire.”

During the Cold War, combat moved away from urban settings, and Fort Irwin’s desert sandbox became the stage for massive set-piece tank battles against the “Soviet” Blackhorse Cavalry. But, in 1993, following the embarrassment of the Black Hawk Down incident in Mogadishu, Fort Irwin hosted its first urban warfare, or MOUT (Military Operations on Urbanized Terrain) exercise. This response was part of a growing realization shared amongst the armed forces, national security experts, and military contractors that future wars would again take the city as their battlefield.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

As Russell W. Glenn of the RAND Corporation puts it bluntly in his report Combat in Hell: A Consideration of Constrained Urban Warfare, “Armed forces are ever more likely to fight in cities as the world becomes increasingly urbanized.”

Massed, professional, and essentially symmetrical armies no longer confront one another on the broad forests and plains of central Europe, the new tactical thinking goes; instead, undeclared combatants living beside—sometimes even with—families in stacked apartment blocks or tight-knit courtyards send out the occasional missile, bullet, or improvised explosive device from a logistically confusing tangle of streets, and “war” becomes the spatial process of determining how to respond.

At Fort Irwin, mock villages began to pop up in the desert. They started out as “sheds bought from Shed World,” Ferrell told us, before being replaced by shipping containers, which, in turn, have been enhanced with stone siding, mosque domes, awnings, and street signs, and, in some cases, even with internal staircases and furniture, too. Indeed, Ertebat Shar/Medina Wasl began its simulated existence in 2007, with just thirteen buildings, but has since expanded to include more than two hundred structures.

The point of these architectural reproductions is no longer, as in the World War II test villages of Dugway, to find better or more efficient methods of architectural destruction; instead, these ersatz buildings and villages are used to equip troops to better navigate the complexity of urban structures—both physical, and, perhaps most importantly, socio-cultural.

In other words, at the most basic level, soldiers will use Fort Irwin’s facsimile villages to practice clearing structures and navigating unmapped, roofed alleyways through cities without clear satellite communications links. However, at least in the training activities accessible to public visitors, the architecture is primarily a stage set for the theater of human relations: a backdrop for meeting and befriending locals (again, paid actors), controlling crowds (actors), rescuing casualties (Fort Irwin’s roster of eight amputees are its most highly paid actors, we learned, in recompense for being literally dragged around during simulated combat operations), and, ultimately, locating and eliminating the bad guys (the Blackhorse regiment).

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

In the series of set-piece training exercises that take place within the village, the action is coordinated from above by a ring of walkie-talkie connected scenographers, including an extensive internal media presence, who film all of the simulations for later replay in combat analysis. The sense of being on an elaborate, extremely detailed film set is here made explicit. In fact, visitors are openly encouraged to participate in this mediation of the events: we were repeatedly urged to take as many photographs as possible and to share the resulting images on Facebook, Twitter, and more.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

Appropriately equipped with ear plugs and eye protection, we filed upstairs to a veranda overlooking one of the village’s main throughways, where we joined the “Observer Coaches” and film crew, taking our positions for the afternoon’s scripted exercise.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

Loud explosions, smoke, and fairly grisly combat scenes ensued—and thus, despite their simulated nature, involving Hollywood-style prosthetics and fake blood, please be warned that many of the forthcoming photos could still be quite upsetting for some viewers.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

The afternoon’s action began quietly enough, with an American soldier on patrol waving off a man trying to sell him a melon. Suddenly, a truck bomb detonated, smoke filled the air, and an injured woman began to wail, while a soldier slumped against a wall, applying a tourniquet to his own severed arm.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

In the subsequent chaos, it was hard to tell who was doing what, and why: gun trucks began rolling down the streets, dodging a live goat and letting off round after round as insurgents fired RPGs (mounted on invisible fishing line that blended in with the electrical wires above our heads) from upstairs windows; blood-covered casualties were loaded into an ambulance while soldiers went door-to-door with their weapons drawn; and, in the episode’s climax, a suicide bomber blew himself up directly beneath us, showering our tour group with ashes.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

Twenty minutes later, it was all over. The smoke died down; the actors reassembled, uninjured, to discuss what just occurred; and the sound of blank rounds being fired off behind the buildings at the end of the exercise echoed through the streets.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

Incredibly, blank rounds assigned to a particular exercise must be used during that exercise and cannot be saved for another day; if you are curious as to where your tax dollars might be going, picture paid actors shooting entire magazines full of blank rounds out of machine guns behind simulated Middle Eastern buildings in the Mojave desert. Every single blank must be accounted for, leading to the peculiar sight of a village’s worth of insurgents stooped, gathering used blank casings into their prop kettles, bread baskets, and plastic bags.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

Finally, we descended back down onto the street, dazed, ears ringing, and a little shocked by all the explosions and gunfire. Stepping carefully around pools of fake blood and chunks of plastic viscera, we made our way back to the lobby of the International Hotel for cups of water and a debrief with soldiers involved in planning and implementing the simulation.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

Our hosts there were an interesting mix of earnest young boys who looked like they had successful careers in politics ahead of them, standing beside older men, almost stereotypically hard-faced, who could probably scare an AK-47 into misfiring just by staring at it, and a few female soldiers.

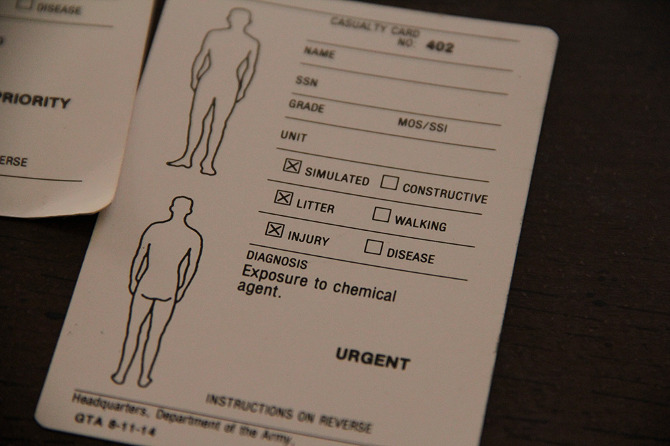

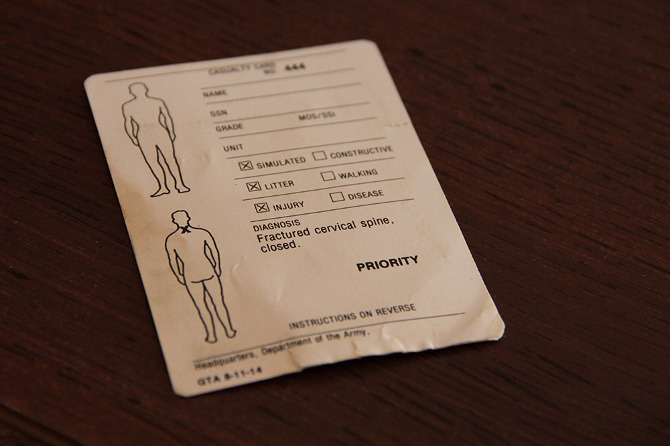

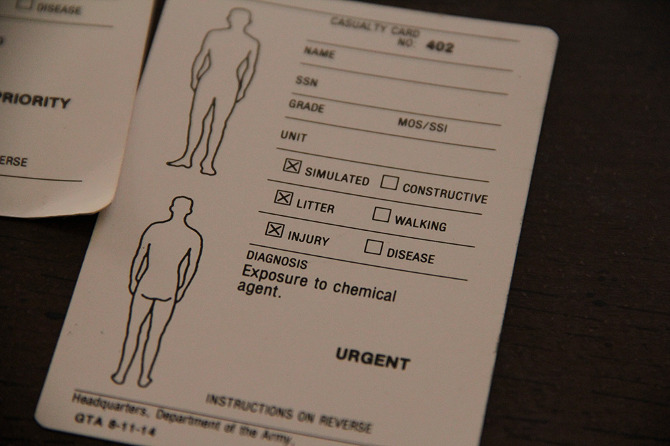

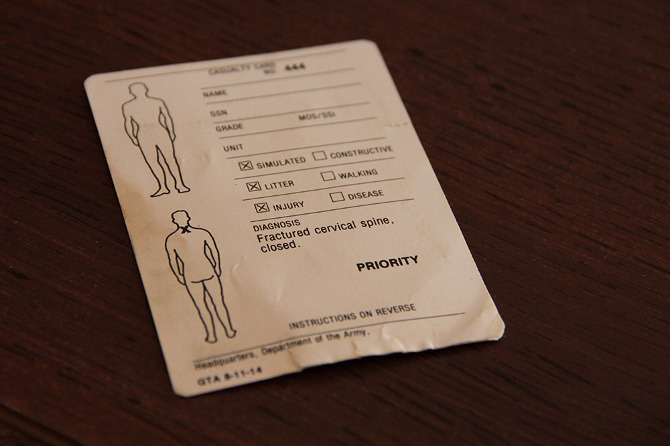

Somewhat subdued at this point, our group sat on sofas that had seen better days and passed around an extraordinary collection of injury cards handed out to fallen soldiers and civilians. These detail the specific rules given for role-playing a suite of symptoms and behavior—a kind of design fiction of military injury.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

A few of us tried on the MILES (Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System) harnesses that soldiers wear to sense hits from fired blanks, and then an enemy soldier demonstrated an exploding door sill.

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

[Images: Photos courtesy of Venue].

While the film crew and Observer Coaches prepared for their “After Action Review,” our guides seemed talkative but unwilling to discuss how well or badly the afternoon’s session had gone. We asked, instead, about the future of Fort Irwin’s villages, as the U.S. withdraws from Afghanistan. The vision is to expand the range of urban conditions into what Ferrell termed a “Decisive Action Training Environment,” in which U.S. military will continue to encounter “the world’s worst actors” [sic]—”guerrillas, criminals, and insurgents”—amidst the furniture of city life.

As he escorted us back down the market street to our bus, one soldier off-handedly remarked that he’d heard the village might be redesigned soon as a Spanish-speaking environment—before hastily and somewhat nervously adding that he didn’t know for sure, and, anyway, it probably wasn’t true.

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Venue].

The “town” is visible on Google Maps, if you’re curious, and it is easy to reach from Barstow. Tours of “The Box” are run twice a month and fill up quickly; learn more at the Fort Irwin website, including safety tips and age restrictions.

• • •For more

Venue content, exploring human interactions with the built, natural, and virtual environments through 16 months of travel around the continental United States, check out the

Venue website in full.

[Image: Dressed in 21st-century personal protective equipment (PPE), I am standing next to Dr. Luigi Bertinato, wearing period plague doctor gear from the time of the Black Death, inside the library of the Querini Stampalia, Venice. Photo by Nicola Twilley.]

[Image: Dressed in 21st-century personal protective equipment (PPE), I am standing next to Dr. Luigi Bertinato, wearing period plague doctor gear from the time of the Black Death, inside the library of the Querini Stampalia, Venice. Photo by Nicola Twilley.] [Image: An arch inside the abandoned lazaretto, or quarantine hospital, on Manoel Island, Malta; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: An arch inside the abandoned lazaretto, or quarantine hospital, on Manoel Island, Malta; photo by Geoff Manaugh.] [Image: Inside the lazaretto at Ancona, Italy; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: Inside the lazaretto at Ancona, Italy; photo by Geoff Manaugh.] [Image: Nicola Twilley inside the high-level isolation unit’s Trexler Ebola system; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: Nicola Twilley inside the high-level isolation unit’s Trexler Ebola system; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]  [Image: Walking inside the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, a salt mine 2,150 feet below the surface of the Earth, where the United States is permanently burying nuclear waste; photo by Nicola Twilley.]

[Image: Walking inside the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, a salt mine 2,150 feet below the surface of the Earth, where the United States is permanently burying nuclear waste; photo by Nicola Twilley.] [Image: Until Proven Safe, with a cover design by Alex Merto.]

[Image: Until Proven Safe, with a cover design by Alex Merto.] [Image: From a project called “

[Image: From a project called “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by  [Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by  [Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by  [Image: Michael Light, from “

[Image: Michael Light, from “ [Image: Michael Light, from “

[Image: Michael Light, from “ [Image: Michael Light, from “

[Image: Michael Light, from “ [Image: Michael Light, from “

[Image: Michael Light, from “ [Image: Michael Light, from “

[Image: Michael Light, from “ [Image: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (

[Image: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (

[Images: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (

[Images: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management ( [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Images: Photo by

[Images: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: The corridors of

[Image: The corridors of  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: “Newton” (1795-c.1805) by William Blake, courtesy of the

[Image: “Newton” (1795-c.1805) by William Blake, courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: From India’s

[Image: From India’s  [Image: Pluto, via

[Image: Pluto, via

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Instruments

[Image: Instruments  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of