[Image: From a project called “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

[Image: From a project called “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

The Bartlett School of Architecture recently put out two new books, freely available for download, FABRICATE 2020 and Design Transactions. Check them both out, as each is filled with incredibly interesting and innovative work.

Purely in the interests of time—by all means, download the books and dive in—I’ll focus on three projects rethinking the use of wood, clay, and ice, respectively, alongside new kinds of concrete formwork and 3D printing.

[Image: From “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

[Image: From “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

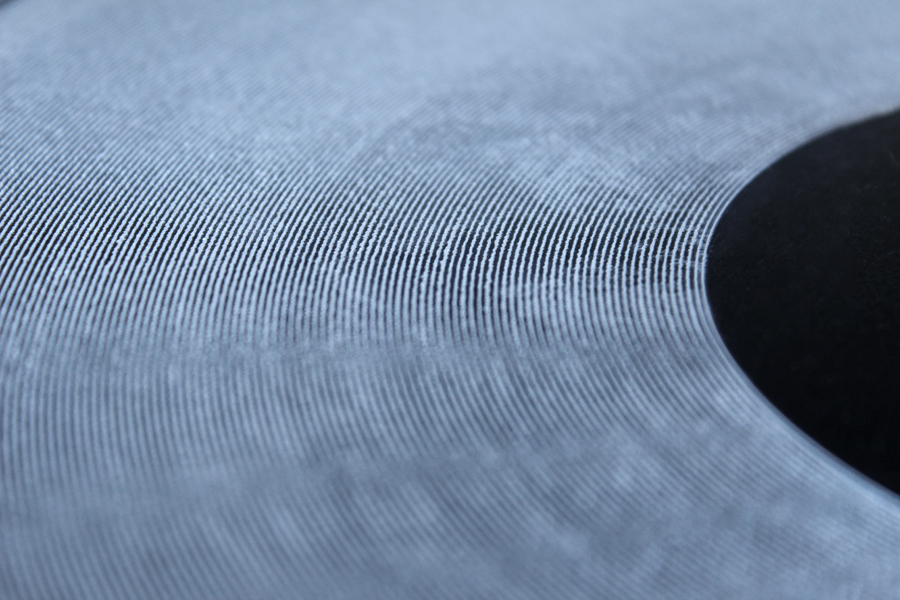

For a project called “Slice,” Sasa Zivkovic and Leslie Lok of design firm HANNAH and Cornell University explore the use of “waste wood” killed by Emerald Ash Borer infestation.

[Image: From “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

[Image: From “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

“Mature ash trees with irregular geometries present an enormous untapped material resource. Through high-precision 3D scanning and robotic fabrication on a custom platform, this project aims to demonstrate that such trees constitute a valuable resource and present architectural opportunities,” they explain.

[Images: From “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

[Images: From “Slice” by HANNAH, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

They continue on their website: “No longer bound to the paradigm of industrial standardization, this project revisits bygone wood craft and design based on organic, found and living materials. Robotic bandsaw cutting is paired with high-precision 3D scanning to slice bent logs from ash trees that are infested by the Emerald Ash Borer.”

I’m reminded of a point made by my wife, Nicola Twilley, in an article for The New Yorker last year about fighting wildfires in California. At one point, she describes attempts “to imagine the outlines of a timber industry built around small trees, rather than the big trees that lumber companies love but the forest can’t spare. In Europe, small-diameter wood is commonly compressed into an engineered product called cross-laminated timber, which is strong enough to be used in multistory structures.”

Seeing HANNAH’s work, it seems that perhaps another way to unlock the potential of small-diameter wood is through robotic bandsaw slicing.

[Image: From “Mud Frontiers” by Emerging Objects, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

[Image: From “Mud Frontiers” by Emerging Objects, as featured in FABRICATE 2020.]

For their project “Mud Frontiers,” Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello use 3D printing and “traditional materials (clay, water, and wheat straw), to push the boundaries of sustainable and ecological construction in a two phase project that explores traditional clay craft at the scale of architecture and pottery.”

[Image: From “Mud Frontiers” by Emerging Objects.]

[Image: From “Mud Frontiers” by Emerging Objects.]

“To do this,” they explain on their website, “we stepped out of the gallery and into the natural environment by constructing a low-cost, and portable robot, designed to be carried into a site where local soils could be harvested and used immediately to 3D print large scale structures.”

[Image: From “Mud Frontiers” by Emerging Objects.]

[Image: From “Mud Frontiers” by Emerging Objects.]

Finally—and, again, I would recommend just downloading the books and spending time with each, as I am barely scratching the surface here—we have a very cool project looking at “ice formwork” for concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov, as featured in Design Transactions.]

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov, as featured in Design Transactions.]

Sitnikov’s method was initially devised as a way to save energy during the concrete-casting and construction process, but quickly revealed its own aesthetic and structural implications: “The variety of programmable functions for ice formwork is vast,” he writes, “across environmental design, programmable lighting conditions, acoustics, ventilation, insulation and structural-design weight-saving applications.”

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov.]

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov.]

He has found, for example, that “spatial patterns… can be imposed on concrete, abandoning any use of petrochemicals in the fabrication process. Breaking away from the ‘solid’ image of conventional concrete, the technique of using ice as the formwork material enables the production of mesoscale spatial structures in concrete which would be impossible to manufacture with existing formwork materials.”

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov.]

[Image: Ice formwork for casting concrete, developed by Vasily Sitnikov.]

Weaving, carving, cutting, molding: the two new Bartlett books have much, much more, including voluminous detail about each of the projects mentioned briefly above, so click on through and go wild: Design Transactions and FABRICATE 2020.

[Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Images: Via the

[Images: Via the

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “

[Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “