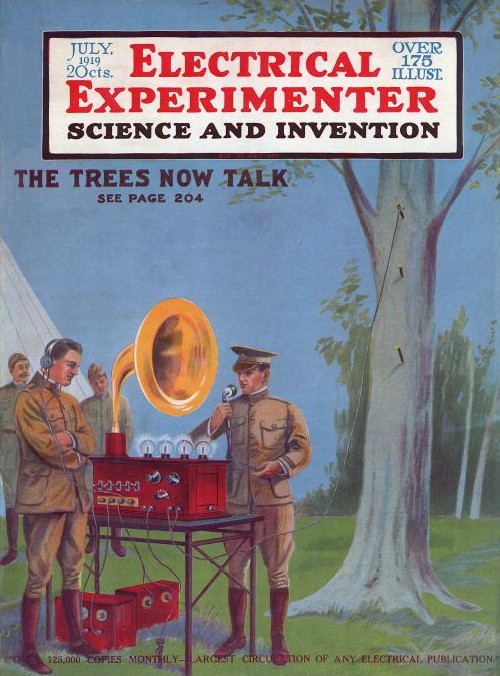

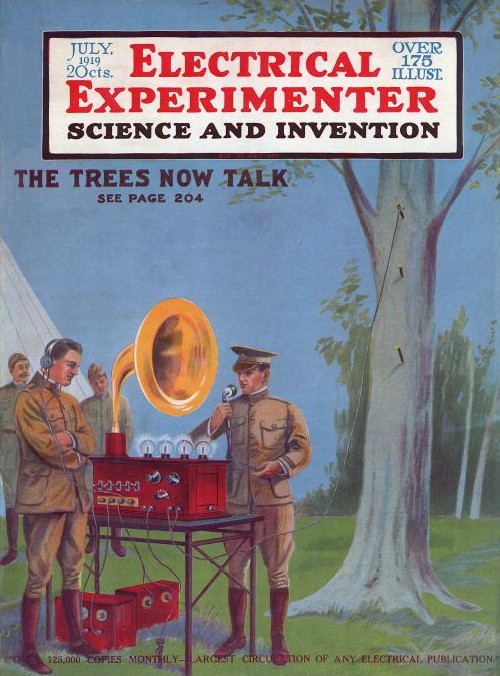

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in The Electrical Experimenter (July 1919); image via rexresearch].

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in The Electrical Experimenter (July 1919); image via rexresearch].

Way back in 1919, in their July 14th issue, Scientific American published an article on the discovery that trees can act “as nature’s own wireless towers and antenna combined.”

General George Owen Squire, the U.S. Army’s Chief Signal Officer, made his “strange discovery,” as SciAm phrases it, while sitting in “a little portable house erected in thick woods near the edge of the District of Columbia,” listening to signals “received through an oak tree for an antenna.” This realization, that “trees—all trees, of all kinds and all heights, growing anywhere—are nature’s own wireless towers and antenna combined.”

He called this “talking through the trees.” Indeed, subsequent tests proved that, “[w]ith the remarkably sensitive amplifiers now available, it was not only possible to receive signals from all the principle [sic] European stations through a tree, but it has developed beyond a theory and to a fact that a tree is as good as any man-made aerial, regardless of the size or extent of the latter, and better in the respect that it brings to the operator’s ears far less static interference.”

Why build a radio station, in a sense, when you could simply plant a forest and wire up its trees?

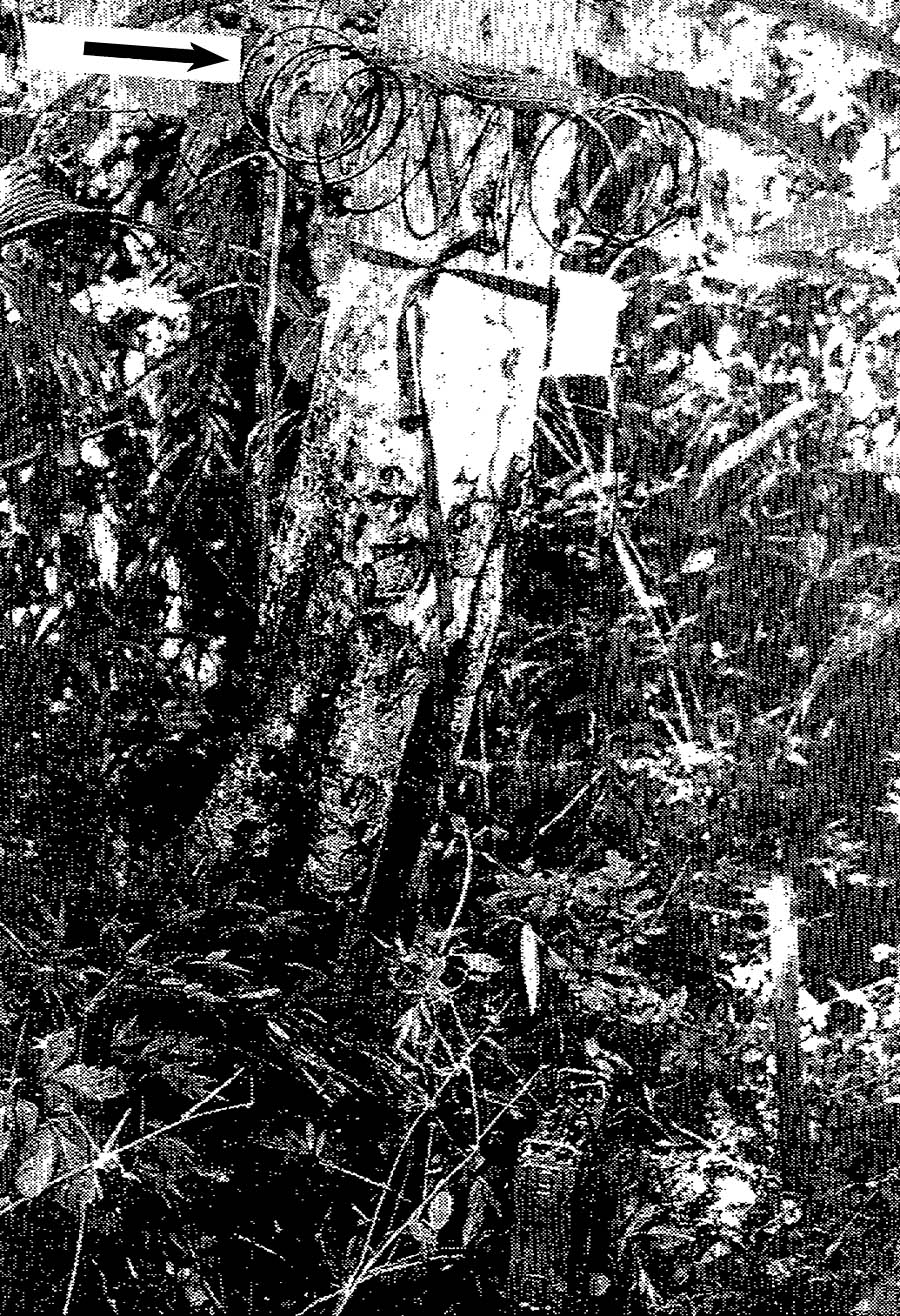

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via rexresearch].

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via rexresearch].

So how does it work? Alas, you can’t just plug your headphones into a tree trunk—but it’s close. From Scientific American:

The method of getting the disturbances in potential from treetop to instrument is so simple as to be almost laughable. One climbs a tree to two-thirds of its height, drives a nail a couple of inches into the tree, hangs a wire therefrom, and attaches the wire to the receiving apparatus as if it were a regular lead-in from a lofty copper or aluminum aerial. Apparently some of the etheric disturbances passing from treetop to ground through the tree are diverted through the wire—and the thermionic tube most efficiently does the rest.

Although “40 nails apparently produce no clearer signals than half a dozen,” one tree can nonetheless “serve as a receiving station for several sets, either connected in series with the same material or from separate terminals.”

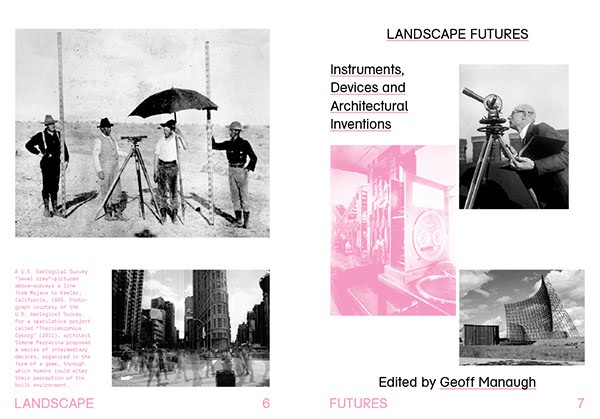

[Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

In a patent filing called “British Patent Specification #149,917,” Squire goes on to explore the somewhat mind-bending possibilities offered by “radio transmission and reception through the use of living vegetable organisms such as trees, plants, and the like.” He writes:

I have recently discovered that living vegetable organisms generally are adapted for transmission and reception of radio or high frequency oscillations, whether damped or undamped, with the use of a suitable counterpoise. I have further discovered that such living organisms are adapted for respectively transmitting or receiving a plurality of separate trains of radio or high frequency oscillations simultaneously, in the communication of either or both telephonic or telegraphic messages.

This research—the field of “tree radio work”—has not disappeared or been forgotten.

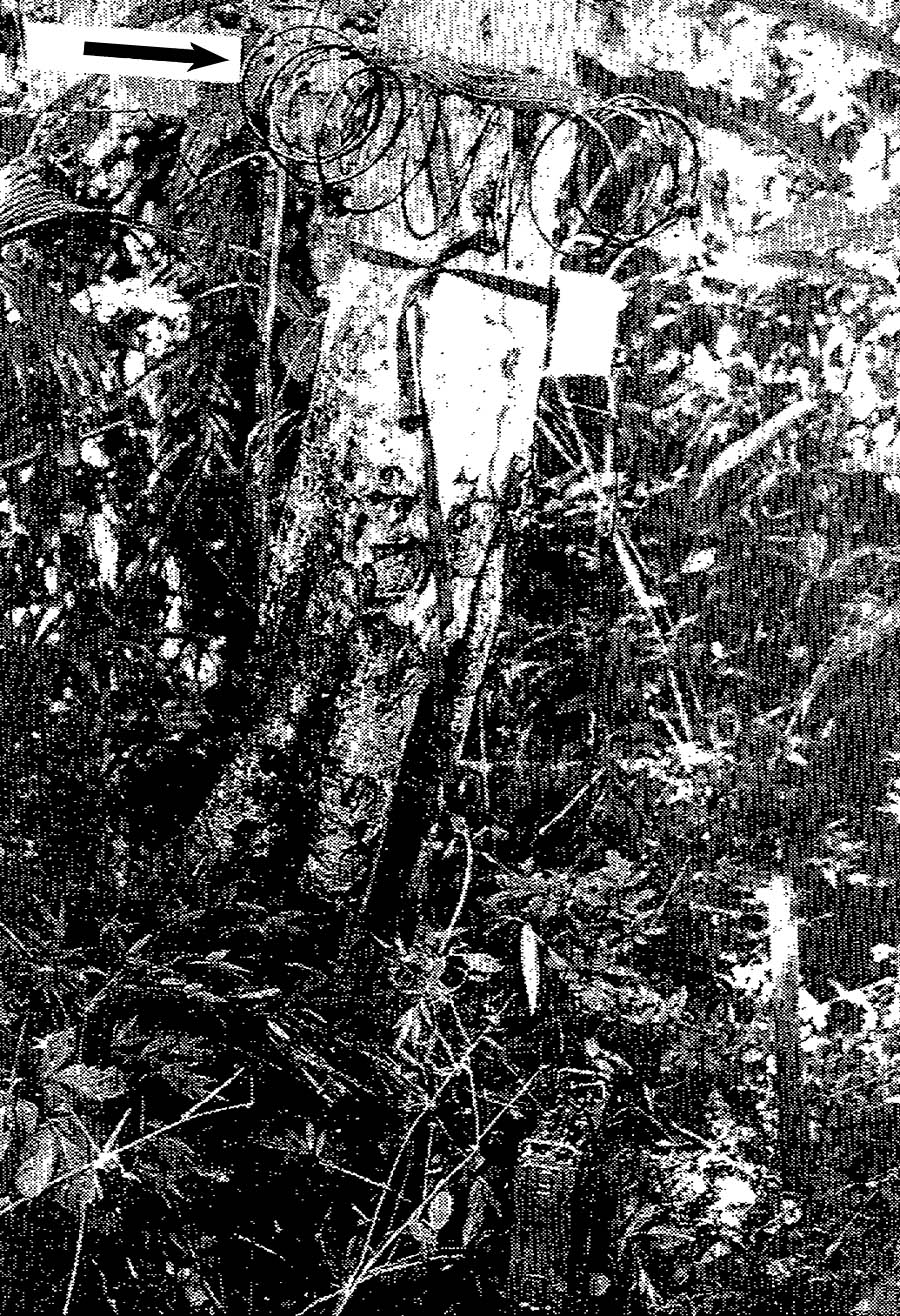

[Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

In the January 1975 issue of IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, we read the test results of several gentleman who went down to the rain forests of the Panama Canal Zone to test “the performance of conventional whip antennas… compared with the performance of trees utilized as antennas in conjunction with hybrid electromagnetic antenna couplers.”

The authors specifically cite Squire’s work and quote him directly: “‘It would seem that living vegetation may play a more important part in electrical phenomena than has been generally supposed… If, as indicated above in these experiments, the earth’s surface is already generously provided with efficient antennae, which we have but to utilize for communications…’ These words were written in 1904 by Major George 0. Squire, U.S. Army Signal Corps, in a report to the Department of War in connection with military maneuvers in the Pacific Division.”

The authors of the IEEE Transactions report thus establish up a jungle-radio “Test Area” in a remote corner of Panama, complete with trees wired-up as dual senders & receivers. There, they think they’ve figured out what’s occurring on a large scale, as signals propagate through the forest canopy, writing that we should consider “the jungle as a maze of aperture-coupled screen rooms. In the jungle case, the screens, in the form of vertical tree and fern trunks, and the horizontal forest canopy are of variable thickness, have variable shaped apertures, and are composed of diverse substances that contain mostly water.”

[Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

The design implication of all this is that an ideal radio-receiving forest could be planted and maintained, complete with spatially tuned “aperture-coupled screen rooms” (trees of specific branch-density planted at specific distances from one another) to allow for the successful broadcast of messages (and/or music) through the “living vegetable organisms” that Squire wrote about in his patent application.

What other creatures—such as birds, bats, wandering children, foxes, or owls—might make of such a landscape, planted not for aesthetic or ecological reasons, but for the purpose of smoothly relaying foreign radio transmissions and encrypted spy communications, is bewildering to contemplate.

In any case, this truly alien vision of forests silently crackling inside with unexploited radio noise is incredible, implying the existence of undiscovered “broadcasts” of biological noise, humming trunk to trunk amongst groves of remote forests like arboreal whale song, inaudible to human ears, as well as suggesting a near-miraculous venue for future concerts, where music would be played not through wireless headsets or hidden speakers lodged in the woods but through the actual trees, music shimmering from root to canopy, filling trees branch and grain with symphonies, drones, rhythms, songs, sounds occasionally breaking through car radios as they speed past on roads nearby.

[All links found via an old message from Shawn Korgan posted to the Natural Radio VLF Discussion Group of which I am a non-participating member. Vaguely related: The Duplicative Forest and Pruned’s Graffiti as Tactical Urban Wireless Network. See also a follow-up post: Antarctic Island Radio].

[Image: Courtesy Capella Space.]

[Image: Courtesy Capella Space.] [Image:

[Image:

[Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: Internal title page from

[Image: Internal title page from

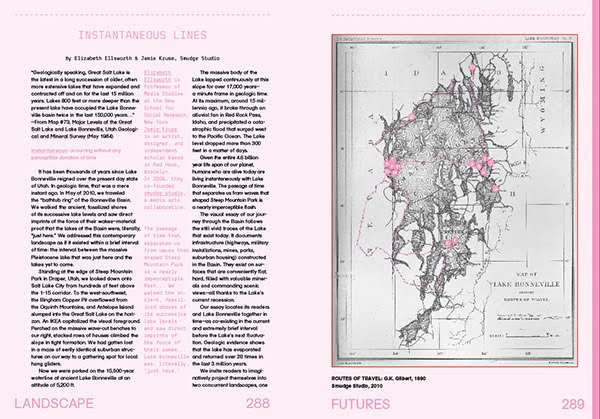

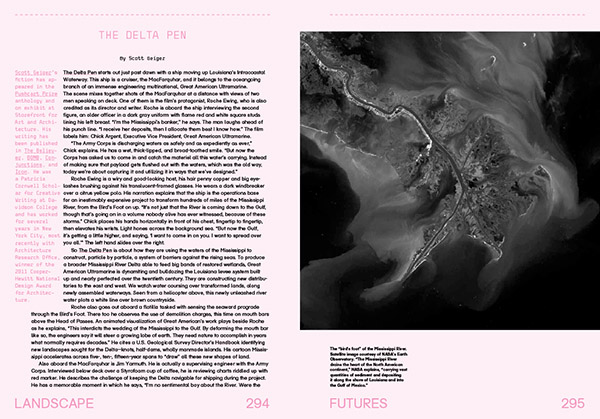

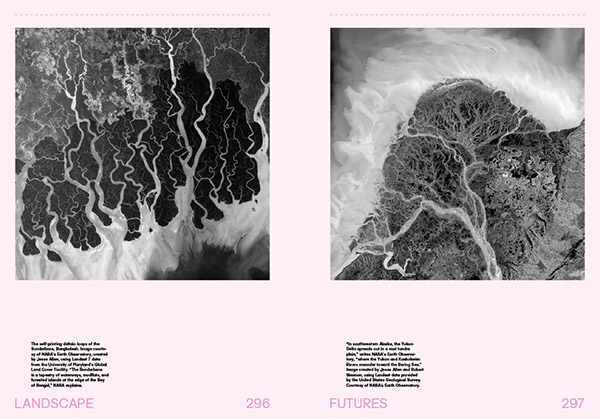

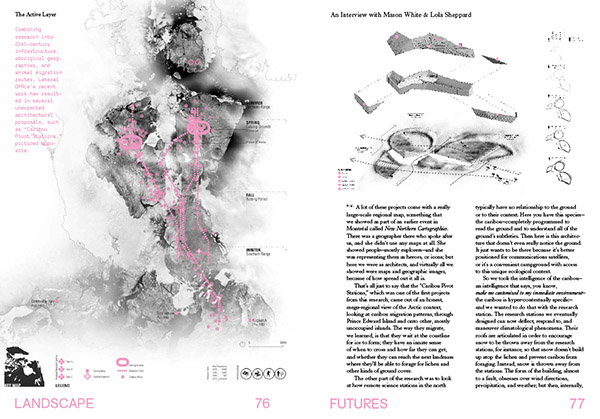

[Images: A few spreads from the “Landscape Futures Sourcebook” featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the “Landscape Futures Sourcebook” featured in

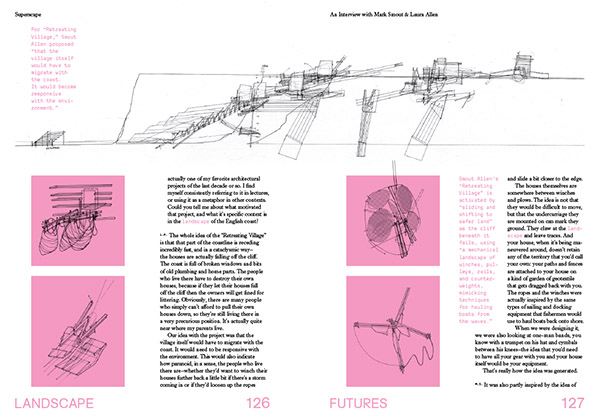

[Images: Interview spreads from

[Images: Interview spreads from

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “

[Image: Like the rings of Saturn, from “

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via  [Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].