[Image: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

[Image: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

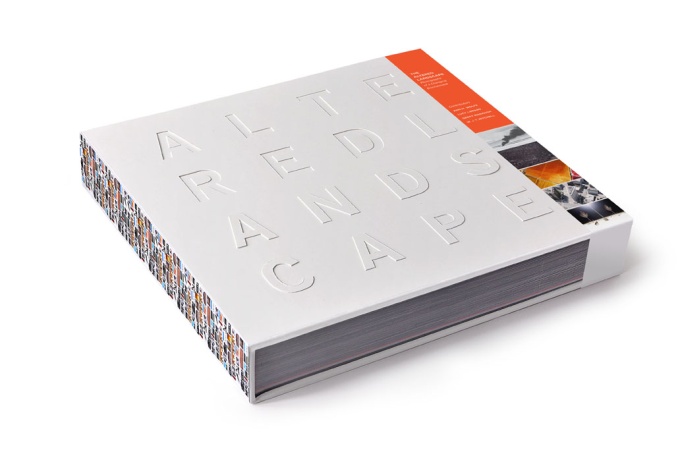

I mentioned a recent issue of Mark Magazine the other day, but I deliberately saved one of the articles for a stand-alone post later on. That article was a long profile of the work of Philip Beesley, a Toronto-based architect and sculptor, whose project the “Implant Matrix” BLDGBLOG covered several years ago.

In issue #21 of Mark, author Terri Peters describes several of Beesley’s projects, but it’s the “Endothelium” that really stood out (and that you see pictured here).

[Image: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

[Image: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

Peters refers to Beesley’s work as a “lightweight landscape of moving, licking, breathing and swallowing geotextile mesh” – a kind of pornography of ornament, or the Baroque by way of David Cronenberg. “Inspired by coral reefs,” she continues, “with their cycles of opening, clamping, filtering and digesting,” Beesley’s biomechanical sculpture-spaces are “immersive theatre environments” in which “wheezing air pumps create an environment with no clear beginning or end.”

I’m reminded of the penultimate scene in James Cameron’s film Aliens, when Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) meets the alien “queen.” The queen is laying eggs, we see, through a gigantic, semi-prosthetic, peristaltically-powered external ovarian sac – and the scene exemplifies the encounter with the grotesque in all its H.R. Giger-influenced, sci-fi extremes. Put another way, if organisms, too – not just buildings – can reach a point of ornamental excess, then James Cameron’s aliens are perhaps exhibit number one.

[Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

In any case, Beesley’s work is a fascinating hybrid of advanced textile design, geostructural modeling, and rogue biology experiment. Peters’s descriptions of the “Endothelium” are worth quoting at length:

[The structure consists of] a field of organic “bladders” that are self-powered and that move very slowly, self-burrowing, self-fertilizing and are linked by 3D printed joints and thin bamboo scaffolding. The bladders are powered using mobile phone vibrators and have LED lights. It works by using tiny gel packs of yeast which burst and fertilize the geotextile.

This latter detail – “using tiny gel packs of yeast which burst and fertilize the geotextile” – brings to mind something at the intersection of an improvised explosive device (or IED) and a green roof: you hire Philip Beesley to design a landscape-machine for installation atop a new building downtown, and, over the course of many decades, it vibrates, yeast-bursts, rotates, crawls, and grows through extraordinary cycles of grotesque architectural fertility. A solar-powered landscape of mold and microroots, generating its own soil. Within a few years, the original sculpture it all came from is gone, archaeologically undetectable beneath the vitality of the forms that have consumed it.

One wonders what Philip Beesley would think of the mushroom tunnel of Mittagong.

[Images: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

[Images: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

Elsewhere in the article, Peters writes:

Endothelium is an automated geotextile, a lightweight and sculptural field housing arrays of organic batteries within a lattice system that might reinforce new growth. It uses a dense series of thin “whiskers” and burrowing leg mechanisms to support low-power miniature lights, pulsing and shifting in slight increments. Within this distributed matrix, microbial growth is fostered by enriched seed-patches housed within nest-like forms, sheltered beneath the main lattice units.

I’m a bit rhetorically stuck on “between” statements, I’m afraid, but it’s as if Beesley’s work falls somewhere between a loaf of sourdough bread and a sculpture by Jean Tinguely.

[Image: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

[Image: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

I’m curious, meanwhile, if you could bury a Philip Beesley sculpture in the woods of rural England somewhere, and allowed it to articulate new ecosystems slowly, over the cyclic course of generations. In fact, I’m reminded of an article in the New York Times last week, spotted via mammoth, in which we learn that two abandoned landfills in Brooklyn have since been used as unlikely foundations for new ecosystems:

In a $200 million project, the city’s Department of Environmental Protection covered the Fountain Avenue Landfill and the neighboring Pennsylvania Avenue Landfill with a layer of plastic, then put down clean soil and planted 33,000 trees and shrubs at the two sites. The result is 400 acres of nature preserve, restoring native habitats that disappeared from New York City long ago.

“Once the plants take hold,” the article adds, “nature will be allowed to take its course, evolving the land into microclimates.” But what if those weren’t landfills down there but sculptures by Philip Beesley? Strategically sown seed-patches and gel packs of yeast wait underground for new roots to rediscover them.

It’s living geostatuary, buried beneath the surface of the earth – a kind of extreme agriculture, with soil-preparation by Philip Beesley.

[Images: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

[Images: “Endothelium” by Philip Beesley & Hayley Isaacs].

I’d genuinely like to see what Beesley might do if he was hired by, say, a NASA R&D program dedicated to terraforming other planets. Could you fly a modular, self-unfolding Philip Beesley sculpture into the depths of radiative space, land it on a planet somewhere, and watch as revolting pools of bacteriological mucus begin to coagulate and form new fungi?

Beesley’s whiskered vibrators begin to shiver with signs of piezoelectric life, as small crystals surrounded by radio transmitters and genetically engineerined space-seed-patches imperceptibly tremble, evolving into mutation-prone “organic batteries” unprotected beneath starlight. Give it a thousand years, and vast infected forests, the width of continents, take hold.

You’ve colonized a distant planet through architecture and yeast.

For more, check out Mark Magazine‘s issue #21. Beesley’s also got a book out, called Hylozoic Soil, that I would love to read.

[Images: From Six Significant Landscapes by Kylie White; photos courtesy Moskowitz Bayse.]

[Images: From Six Significant Landscapes by Kylie White; photos courtesy Moskowitz Bayse.] [Image: “Model of Earth Fastener on a Transform Fault; 1”=10” (2017) by Kylie White; note that this piece was not featured in Six Significant Landscapes. Photo courtesy Moskowitz Bayse.]

[Image: “Model of Earth Fastener on a Transform Fault; 1”=10” (2017) by Kylie White; note that this piece was not featured in Six Significant Landscapes. Photo courtesy Moskowitz Bayse.] [Image: From Six Significant Landscapes by Kylie White; photo courtesy Moskowitz Bayse.]

[Image: From Six Significant Landscapes by Kylie White; photo courtesy Moskowitz Bayse.]

[Images: Details from Six Significant Landscapes by Kylie White; photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Images: Details from Six Significant Landscapes by Kylie White; photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: R. Fu, via

[Image: R. Fu, via  [Image: An installation view of

[Image: An installation view of

[Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image: From

[Image: From  The Museum has also recently announced a discounted

The Museum has also recently announced a discounted  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: “Electric Aurora” by Liam Young, from Specimens of Unnatural History].

[Image: “Electric Aurora” by Liam Young, from Specimens of Unnatural History]. [Image: From The Active Layer by Lateral Office; photo by

[Image: From The Active Layer by Lateral Office; photo by  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “