[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

The Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota, was once “the largest, deepest and most productive gold mine in North America,” featuring nearly 370 miles’ worth of tunnels.

Although active mining operations ceased there more than a decade ago, the vast subterranean labyrinth not only remains intact, it has also found a second life as host for a number of underground physics experiments.

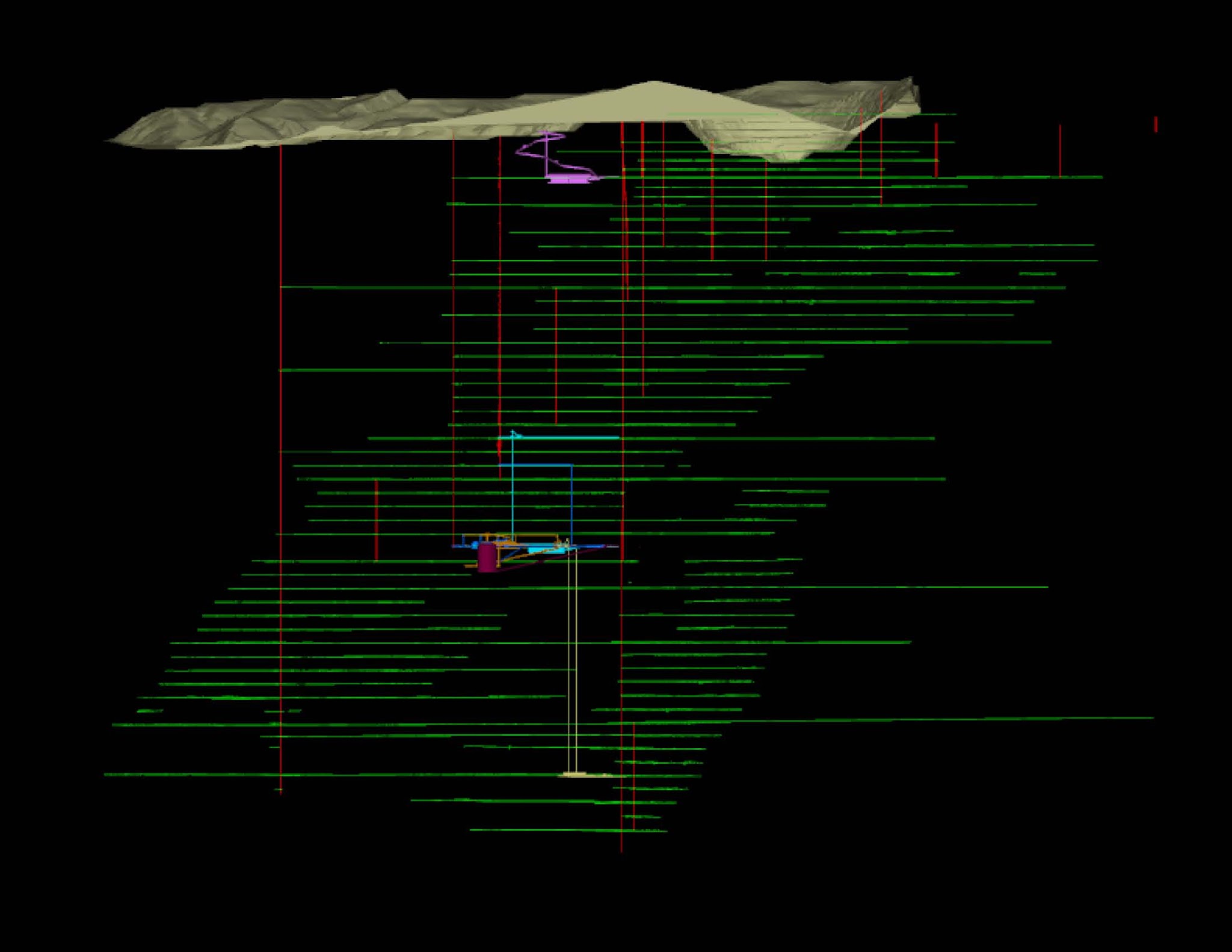

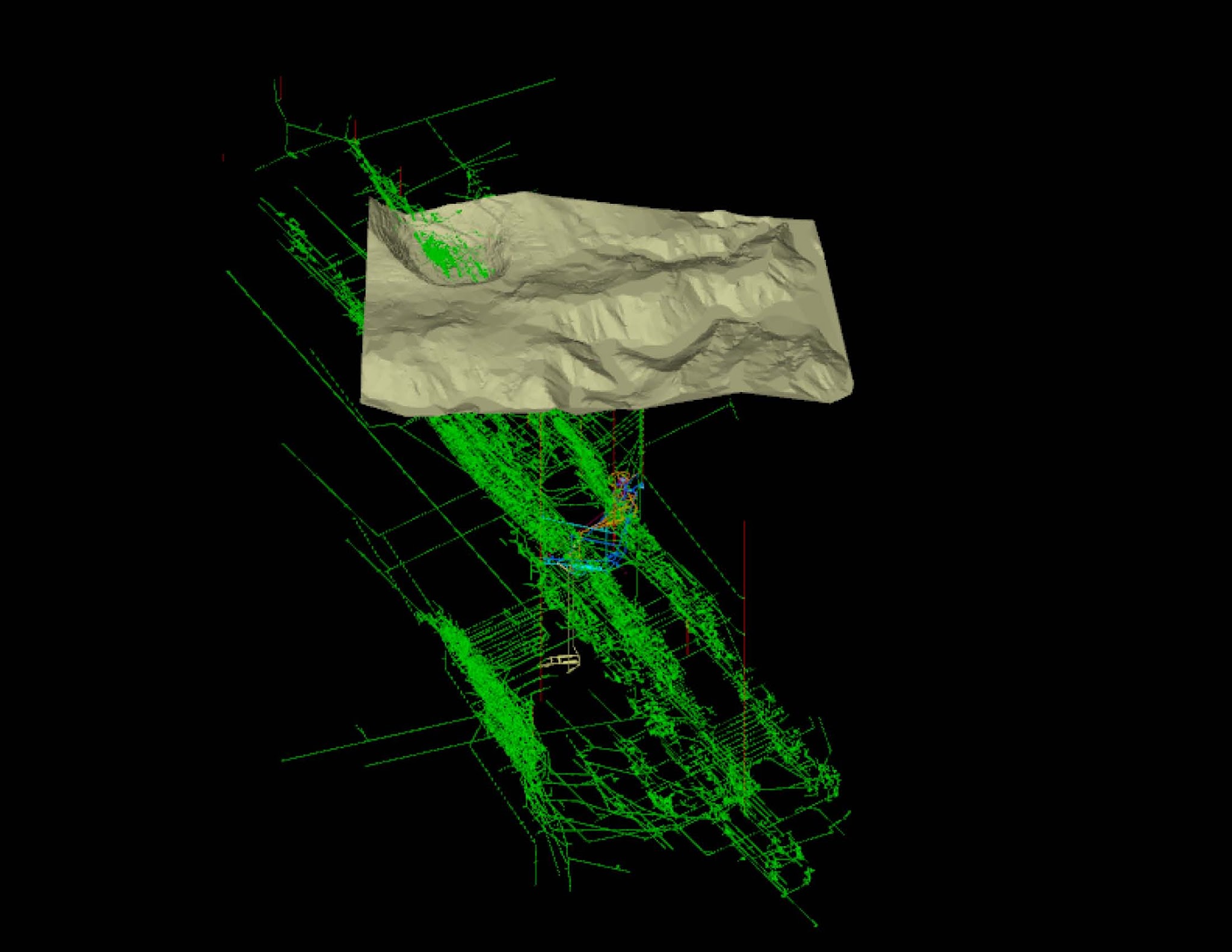

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

These include a lab known as the Sanford Underground Research Facility, as well as a related project, the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory (or DUSEL).

Had DUSEL not recently run into some potentially fatal funding problems, it “would have been the deepest underground science facility in the world.” For now, it is on hold.

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

There is already much to read about the experiments going on there, but one of the key projects underway is a search for dark matter. As Popular Science explained back in 2010:

Now a team of physicists and former miners has converted Homestake’s shipping warehouse into a new surface-level laboratory at the Sanford Underground Laboratory. They’ve painted the walls and baseboards white and added yellow floor lines to steer visitors around giant nitrogen tanks, locker-size computers and plastic-shrouded machine parts. Soon they will gather many of these components into the lab’s clean room and combine them into LUX, the Large Underground Xenon dark-matter detector, which they will then lower halfway down the mine, where—if all goes well—it will eventually detect the presence of a few particles of dark matter, the as-yet-undetected invisible substance that may well be what holds the universe together.

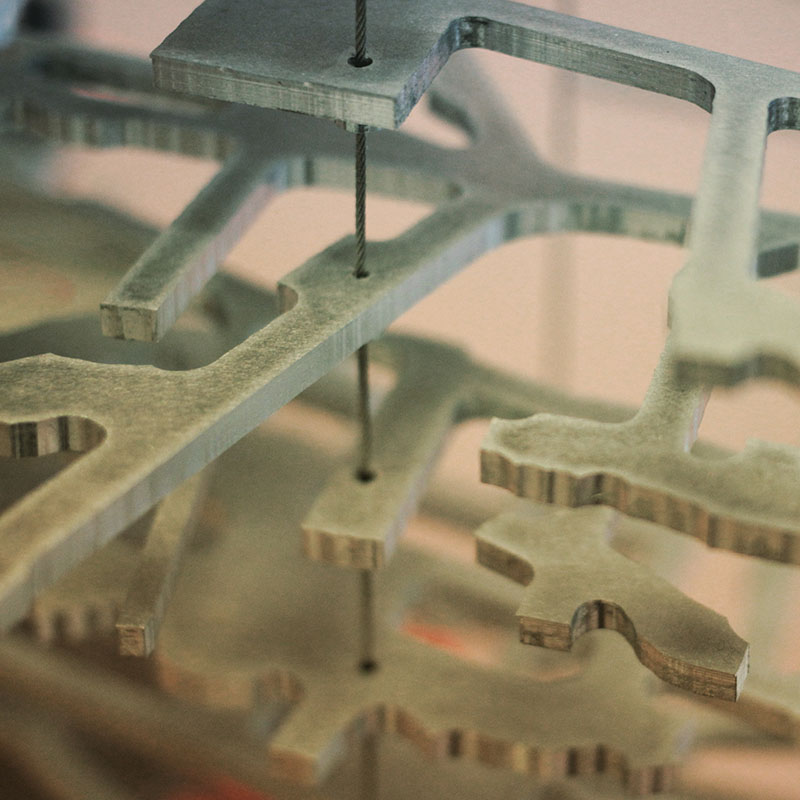

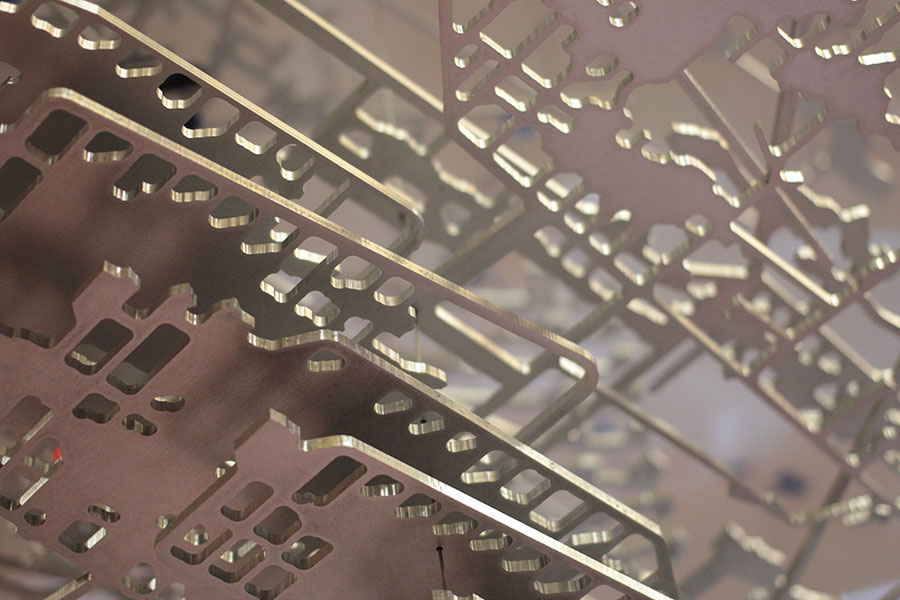

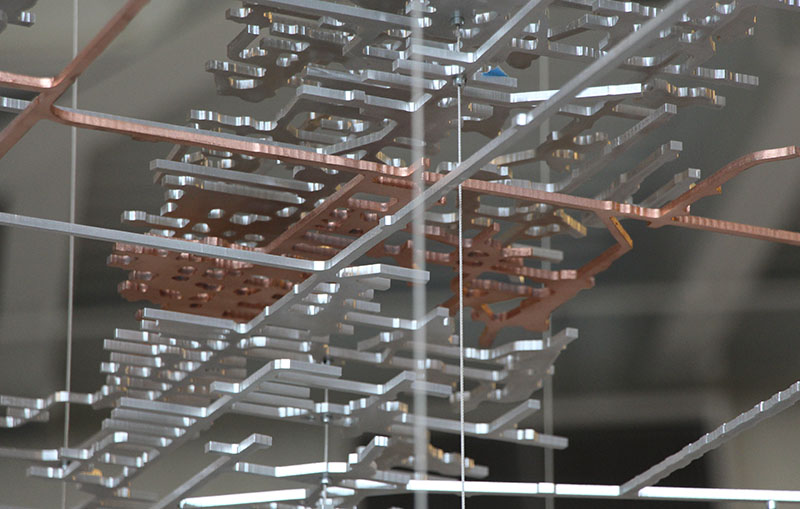

Earlier this year, I was scrolling through my Instagram feed when I noticed some cool photos popping up from a Brooklyn-based firm called SITU Fabrication. The images showed what appeared to be a maze of strangely angled metal parts and wires, hanging from one another in space.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by SITU Fabrication].

One of them—seen above, and resembling some sort of exploded psychogeographic map of Dante’s Inferno—was simply captioned, “#CNC milled aluminum plates for model of underground tunnel network in #SouthDakota.”

Living within walking distance of the company’s DUMBO fabrication facility, I quickly got in touch and, a few days later, stopped by to learn more.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

SITU’s Wes Rozen met me for a tour of the workshop and a firsthand introduction to the Homestake project.

The firm, he explained, already widely known for its work on complex fabrication jobs for architects and artists alike, had recently been hired to produce a 3D model of the complete Homestake tunnel network, a model that would later be installed in a visitors’ center for the mine itself.

Visitors would thus encounter this microcosm of the old mine, in lieu of physically entering the deep tunnels beneath their feet.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

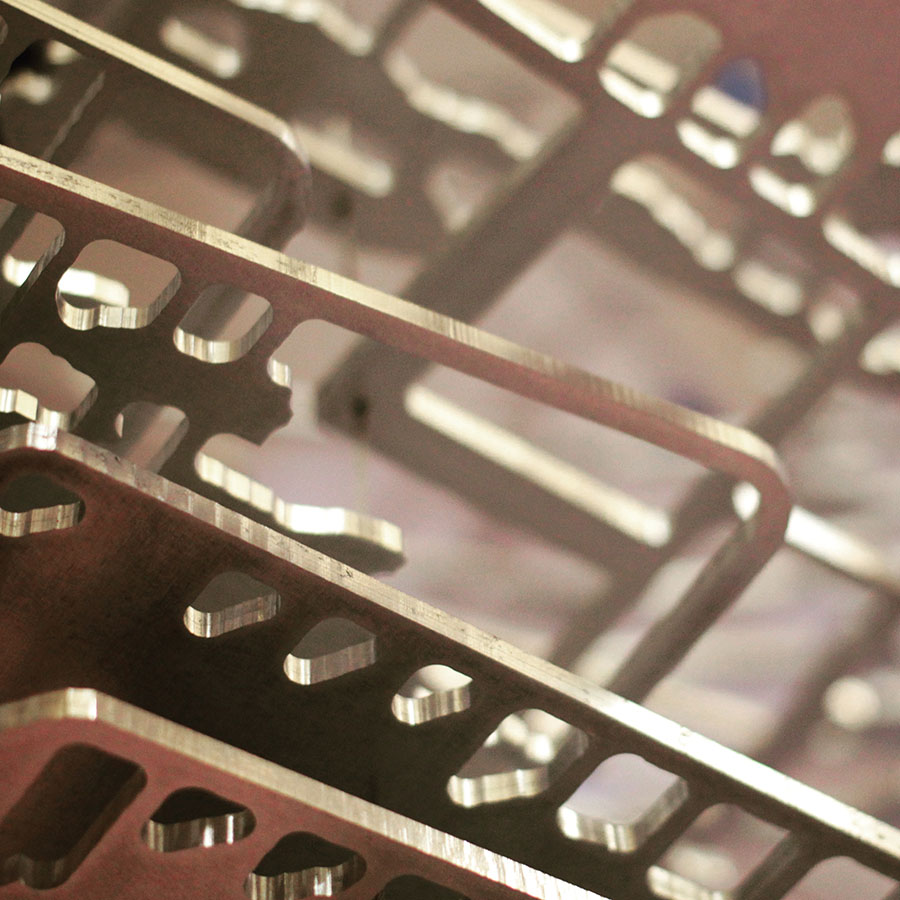

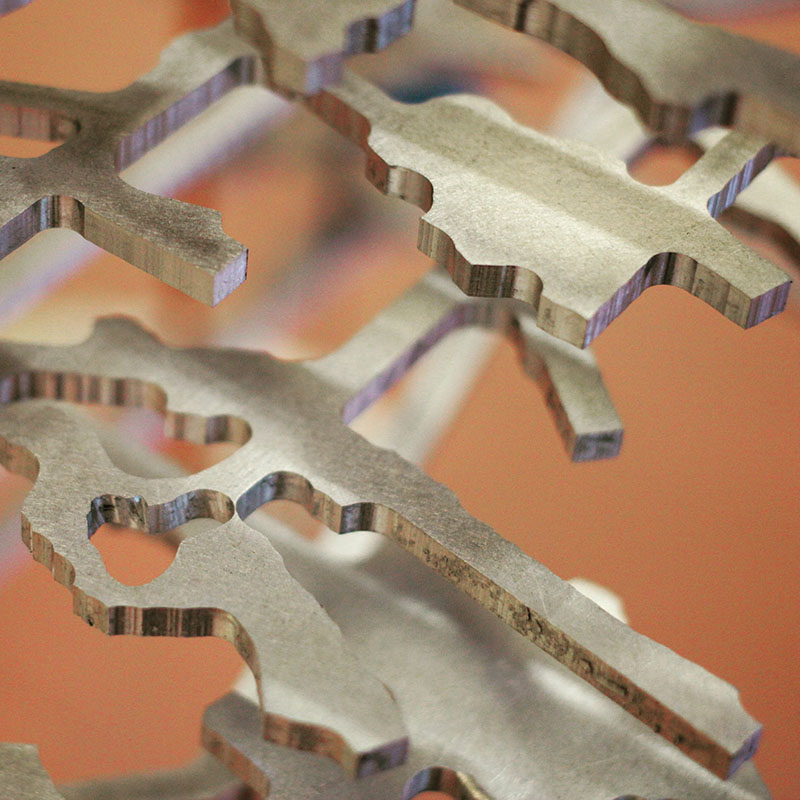

Individual levels of the mine, Rozen pointed out, had been milled from aluminum sheets to a high degree of accuracy; even small side-bays and dead ends were included in the metalwork.

Negative space became positive, and the effect was like looking through lace.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

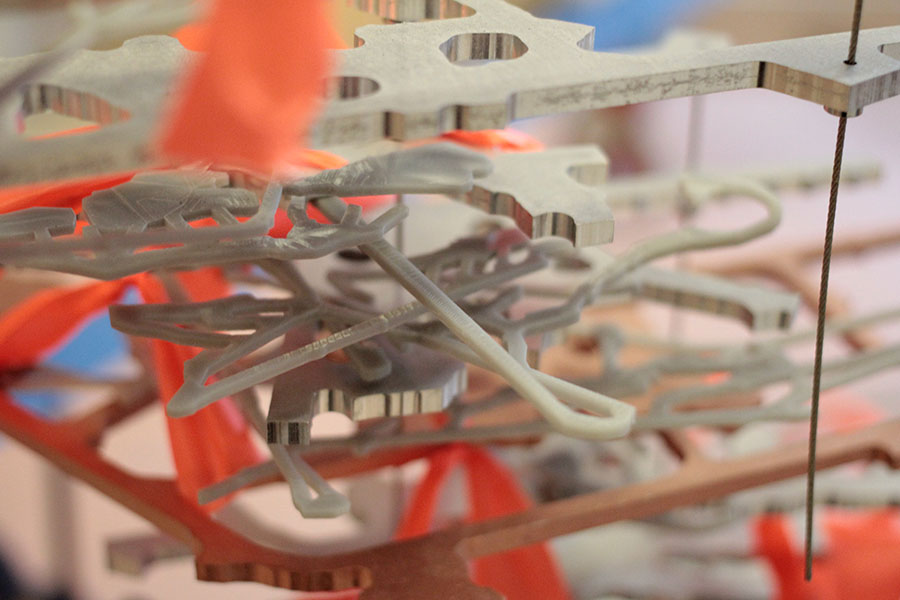

Further, tiny 3D-printed parts—visible in some photographs, further below—had also been made to connect each level to the next, forming arabesques and curlicues that spiraled out and back again, representing truck ramps.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

The whole thing was then suspended on wires, hanging like a chandelier from the underworld, to form a cloud or curtain of subtly reflective metal.

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

When I showed up that day, the pieces were still being assembled; small knots of orange ribbon and pieces of blue painter’s tape marked spots that required further polish or balancing, and metal clamps held many of the wires in place.

[Images: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos by BLDGBLOG].

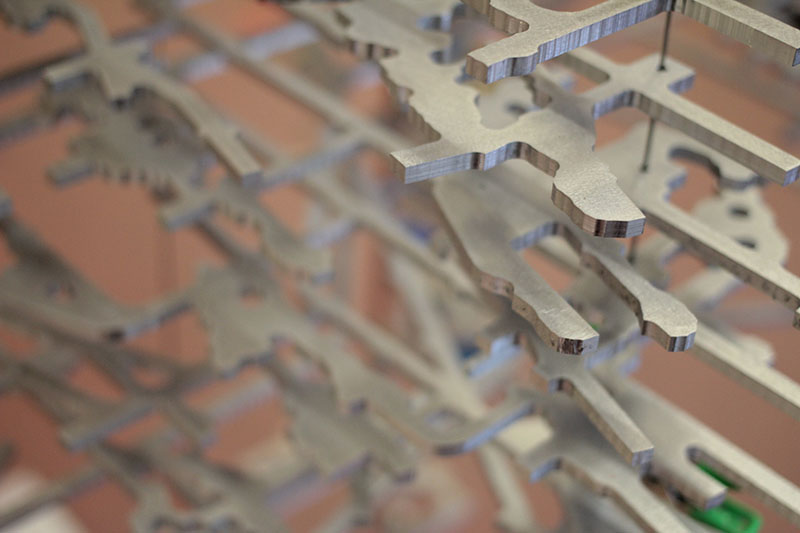

Seen in person, the piece is astonishingly complex, as well as physically imposing—in photographs, unfortunately, this can be difficult to capture.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

However, the sheer density of the metalwork and the often impossibly minute differences from one level of the mine to the next—not to mention, at the other extreme, the sudden outward spikes of one-off, exploratory mine shafts, shooting away from the model like blades—can still be seen here, especially in photos supplied by SITU themselves.

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

A few of the photos look more like humans tinkering in the undercarriage of some insectile aluminum engine, a machine from a David Cronenberg movie.

[Image: Assembling the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Assembling the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

Which seems fitting, I suppose, as the other appropriate analogy to make here would be to the metal skeleton of a previously unknown creature, pinned up and put together again by the staff of an unnatural history museum.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

The model is now complete and no longer in Brooklyn: it is instead on display at the Homestake visitors’ center in South Dakota, where it greets the general public from its perch above a mirror. As above, so below.

[Images: The model seen in situ, by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Images: The model seen in situ, by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

Again, it’s funny how hard the piece can be to photograph in full, and how quick it is to blend into its background.

This is a shame, as the intricacies of the model are both stunning and worth one’s patient attention; perhaps it would be better served hanging against a solid white background, or even just more strategically lit.

[Image: The model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: The model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

Or, as the case may be, perhaps it’s just worth going out of your way to see the model in person.

Indeed, following the milled aluminum of one level, then down the ramps to the next, heading further out along the honeycomb of secondary shafts and galleries, and down again to the next level, and so on, ad infinitum, was an awesome and semi-hypnotic way to engage with the piece when I was able to see it up close in SITU’s Brooklyn facility.

I imagine that seeing it in its complete state in South Dakota would be no less stimulating.

(Vaguely related: Mine Machine).

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From