Speaking of animals being actively incorporated into urban infrastructure, Dutch police are training eagles to hunt drones. “What I find fascinating is that birds can hit the drone in such a way that they don’t get injured by the rotors,” explains a spokesperson for the National Audubon Society. “They seem to be whacking the drone right in the center so they don’t get hit; they have incredible visual acuity and they can probably actually see the rotors.”

Tag: Infrastructure

Under the Bridge

Photographer Gisela Erlacher has been documenting “the spaces found hidden underneath highways and flyovers across Europe and China,” as seen in the many photos posted over at Creative Boom. “Each photograph reveals not only her own fascination with these massive concrete monstrosities, but also her interest in how they’re now being used by the people who choose to wedge themselves into these forgotten areas.”

Avian Infrastructure

[Image: The turkey vulture’s “verification flight pattern,” taken from “The Role of Olfaction in Food Location by the Turkey Vulture” by Kenneth E. Stager (PDF)].

[Image: The turkey vulture’s “verification flight pattern,” taken from “The Role of Olfaction in Food Location by the Turkey Vulture” by Kenneth E. Stager (PDF)].

In an article for New Scientist last year, I wrote about the expansion of urban infrastructure to include animal life, from pigs serving a de facto waste-management role in cities such as Cairo to falcons being used to patrol a Santa Monica business park against, less welcome species.

It was thus interesting to read last night that the noxious smell artificially introduced to otherwise odorless natural gas was originally added, at least partially, because it would attract turkey vultures.

In a 1964 paper by Kenneth E. Stager called “The Role of Olfaction in Food Location by the Turkey Vulture” (PDF) we read that the “decision to conduct field tests with ethyl mercaptan (CH3CH2SH) as an olfactory attractant for turkey vultures came as a result of conversations with field engineers of the Union Oil Company of California.” Its purpose would be “to aid in locating leaks in natural gas lines”:

It was suggested to them by a company engineer in Texas that an effective way of locating line leaks in rough terrain was to introduce a heavy concentration of ethyl mercaptan into the line and then patrol the route and observe the concentrations of turkey vultures circling or sitting on the ground at definite points along the line… A high concentration of ethyl mercaptan was introduced into the forty-two miles of gas line and a traverse of the route was made. At several points along the line, turkey vultures were observed either circling or sitting on the ground. At those locations the odor of the ethyl mercaptan was very pronounced and examination of the line revealed the leaks.

There are at least two things worth highlighting here: one is the strange image of 20th-century oil company employees wandering through “rough terrain” in coordinated synchrony with families of turkey vultures, in effect bringing avian labor into the international supply chain of petroleum products.

It’s the turkey vulture as corporate companion species: a living being enlisted for assistance in shepherding—or flocking, as it were—natural gas to the final customer. It seems almost medieval.

But the second thing that seems worth commenting on is the broader implication that natural gas was made to smell like death—to smell like rotting corpses—thus becoming attractive to flocks of turkey vultures. This brings to mind Reza Negarestani’s book, Cyclonopedia, where Negarestani refers to the oil industry in only somewhat fictional terms as a kind of industrial cult organized around what he calls “the black corpse of the sun”: that is, oil, with all of its volatile by-products, the remnant hydrocarbons of once-living things, transformed through millions of years of burial.

That we would make petroleum gas smell like dead animals seems almost perfectly ironic, giving this image of necromantic Union Oil employees out scouting the backlands of Texas and California looking for gas leaks, following airborne animal trails, an even more bizarre interpretive bearing.

(Vulture anecdote originally spotted on Twitter, thanks to a retweet from @carlzimmer).

Ghost Streets of Los Angeles

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

In a short story called “Reports of Certain Events in London” by China Miéville—a text often cited here on BLDGBLOG—we read about a spectral network of streets that appear and disappear around London like the static of a radio tuned between stations, old roadways that are neither here nor there, flickering on and off in the dead hours of the night.

For reasons mostly related to a bank heist described in my book, A Burglar’s Guide to the City, I found myself looking at a lot of aerial shots of Los Angeles—specifically the area between West Hollywood and Sunset Boulevard—when I noticed this weird diagonal line cutting through the neighborhood.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

It is not a street—although it obviously started off as a street. In fact, parts of it today are still called Marshfield Way.

At times, however, it’s just an alleyway behind other buildings, or even just a narrow parking lot tucked in at the edge of someone else’s property line.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

Other times, it actually takes on solidity and mass in the form of oddly skewed, diagonal slashes of houses.

The buildings that fill it look more like scar tissue, bubbling up to cover a void left behind by something else’s absence.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

First of all, I love the idea that the buildings seen here take their form from a lost street—that an old throughway since scrubbed from the surface of Los Angeles has reappeared in the form of contemporary architectural space.

That is, someone’s living room is actually shaped the way it is not because of something peculiar to architectural history, but because of a ghost street, or the wall of perhaps your very own bedroom takes its angle from a right of way that, for whatever reason, long ago disappeared.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

If you follow this thing from roughly the intersection of Hollywood & La Brea to the strangely cleaved back of an apartment building on Ogden Drive—the void left by this lost street, incredibly, now takes the form of a private swimming pool—these buildings seem to plow through the neighborhood like train cars.

Which could also be quite appropriate, as this superficial wound on the skin of the city is most likely a former streetcar route.

But who knows: my own research went no deeper than an abandoned Google search, and I was actually more curious what other people thought this might be or what they’ve experienced here, assuming at least someone in the world reading this post someday might live or work in one of these buildings.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

And perhaps this is just the exact same point, repeated, but the notion that every city has these deeper wounds and removals that nonetheless never disappear is just incredible to me. You cut something out—and it becomes a building a generation later. You remove an entire street—and it becomes someone’s living room.

I remember first learning that one of the auditoriums at the Barbican Art Centre in London is shaped the way it is because it was built inside a former WWII bomb crater, and simply reeling at the notion that all of these negative spaces left scattered and invisible around the city could take on architectural form.

Like ghosts appearing out of nowhere—or like China Miéville’s fluttering half-streets, conjured out of the urban injuries we all live within and too easily mistake for property lines and real estate, amidst architectural incisions that someday become swimming pools and parking lots.

*Update* Some further “ghost streets” have popped up in the comments here, and the images are worth posting.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

The one seen above, for example, is “another ghost diagonal that begins on 8th St. at Hobart, and ends at Pico and Rimpau,” an anonymous commenter explains.

Another example, seen below—

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

—is “a block in the Pico-Robertson area,” a commenter writes:

I lived there as a teenager, but never noticed the two diagonals until I looked at it with google maps. There are some lots on the west side of the next two blocks north which also have diagonals. And if you continue north across Pico Blvd, you can see diagonal property lines around St. Mary Magdalene Catholic School and the church.

Thanks for all the tips, and by all means keep them coming, if you are aware of other sites like this, whether in Los Angeles or further afield; and be sure to read through the comments for more.

*Second Update* The examples keep coming. A commenter named Lance Morris explains that he did an MFA project “about this very thing, but in Long Beach. There’s a long diagonal scar running from Long Beach Blvd and Willow all the way down to Belmont Shore. I tried walking as closely to the line as I could and GPS tracked the results. There are even 2 areas where you can still see tracks!”

This inspired me to look around the area a little bit on Google Maps, which led to another place nearby, as seen below.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

Again, seeing how these local building forms have been generated by the outlines of a missing street or streetcar line is pretty astonishing.

Further, the tiniest indicators of these lost throughways remain visible from above, usually in the form of triangular building cuts or geometrically odd storage yards and parking lots. Because they all align—like some strange industrial ley line—you can deduce that an older piece of transportation infrastructure is now missing.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view a bit larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view a bit larger].

Indeed, if you zoom out from there in the map, you’ll see that the subtle diagonal line cutting across the above image (from the lower left to the upper right) is, in fact, an old rail right of way that leads from the shore further inland.

To give a sense of how incredibly subtle some of these signs can be, the diagonal fence seen in the below screen grab—

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

—is actually shaped that way not because of some quirk of the local storage lot manager, but because it follows this lost right of way.

*Third Update* There are yet more interesting examples popping up now over in a thread on Metafilter.

There, among other notable comments, someone called univac points out that the streetcar scar that “begins on 8th St. at Hobart, and ends at Pico and Rimpau”—quoting an earlier commenter here on BLDGBLOG—”actually has one echo in the diagonally-stepped building here, and picks up again in the block bounded by Wilton, Westchester, 9th and San Marino, and ends at a crooked building just north of 4th and Olympic.”

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

You can see the middle stretch of that route in the image, above. For more, check out the thread on Metafilter.

Not only this, however, but the old right of way followed by that commenter actually extends much further than that, all the way southwest to a small park at approximately Pico and Queen Anne Place.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

In the above image, you can see a small structure—a garage or a house—turned slightly off-axis in the northeast corner, indicating the line of the old streetcar line, with some open lawns and small paved areas revealing its obscured geometry as you look down to the southwest.

Five Parises of Emptiness

[Image: Via Curbed LA].

[Image: Via Curbed LA].

Citing a new report in the Journal of the American Planning Association, Curbed LA points out that “parking infrastructure takes up about 200 square miles of land in LA county.”

That’s more than four San Franciscos’ worth of space (46.87 square miles) and nearly five times the size of Paris (40.7 square miles). Or, as Janette Sadik-Khan wrote on Twitter, “LA County has 85% more parking spots than people, occupying more space than the entire city of Philly.”

Los Angeles, where it’s you and a bunch of parking lots.

Shaft

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

Here’s another prosthetic elevator project—in fact, the reason I posted the previous one—this time around designed by architect Carles Enrich for the riverside city of Gironella, Spain.

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

The elevator connects the old and new parts of town, offering ease of access to the young and elderly alike, and reopening social and economic circulation between the two halves of the city.

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

Built using steel, glass, and bricks, the project also blends into the existing color scheme of the city, looking like a chimney or a church steeple, a tower of roofing tiles suddenly standing alongside the city’s cliff.

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

Among many things, I love how unbelievably simple the project is: it’s just a rectangle, going from level A to level B. That’s it.

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

I’m not entirely sure why I find projects like this so fascinating, in fact, but the notion that two radically separate vertical levels can suddenly be connected by the magic of architecture is one of the most fundamental promises of construction in the first place: that, through a clever use of design skills and materials, we can create or discover new forms of circulation and unity.

[Images: Photos by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Images: Photos by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

With staircases, of course, you have more leeway for introducing expressive shifts in direction and orientation, pinching floors together, for example, or introducing elaborate curls leading from one floor to the next.

The elevator, by contrast, seems remarkably sedate.

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

It’s just a box you step into, and a vertical corridor you travel within. In the photo above, it’s like a dimly lit portal peeking up from some other, deeper district of the city.

Yet the ease of connection, and the use of subtle materials to realize it, are immensely exciting for some reason, as if we are all ever just one quick design gesture away from linking parts of the world in ways they never had been previously.

Just build an elevator: a pop-up vertical corridor delivering ascension where you’d least expected it.

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

[Image: Photo by Adrià Goula, courtesy of Carles Enrich].

In any case, read more about the project over at the architect’s own website, or at ArchDaily, where I first saw the project, and check out the previous post for another elevator, while you’re at it.

Lift

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

The forthcoming (i.e. next) post will retroactively serve as an otherwise arbitrary excuse for posting this project, one of my favorites of the last few years, a kind of castellated prosthetic elevator on the island of Malta by Architecture Project.

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

The twenty-story outdoor elevator “required a certain rigour to resolve the dichotomy between the strong historic nature of the site and the demands for better access placed upon it by cultural and economic considerations,” resulting in the choice of blunt industrial materials and stylized perforations.

[Image: Photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: Photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

As the architects describe it:

The geometric qualities of the plan echo the angular forms of the bastion walls, and the corrugated edges of the aluminium skin help modulate light as it hits the structure, emphasizing its verticality. The mesh masks the glazed lift carriages, recalling the forms of the original cage lifts, whilst providing shade and protection to passengers as they travel between the city of Valletta and the Mediterranean Sea.

Personally, I love the idea of what is, in effect, a kind of bolt-on castle, combining the language of one era—the Plug-In Cities of Archigram, say—with the aesthetics of the Knights of Malta.

[Image: Photo by Luis Rodríguez López, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: Photo by Luis Rodríguez López, courtesy of Architecture Project].

In fact, it’s almost tempting to write a design brief explicitly calling for new hybridizations of these approaches: modular, prefab construction… combined with Romanesque fortification.

[Image: Photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: Photo by Sean Mallia, courtesy of Architecture Project].

An emergency stairwell spirals down between the two parallel elevator shafts, which “also reduces the visual weight of the lift structure itself and accentuates the vertical proportions of the structure,” the architects suggest and contributes to perforating the outside surface beyond merely the presence of chainlink.

[Image: Photo by Luis Rodríguez López, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: Photo by Luis Rodríguez López, courtesy of Architecture Project].

In any case, it’s not a new project—like me, you probably saw this on Dezeen way back in 2013—but I was just glad to have a random excuse to post it.

[Image: Photo by Luis Rodríguez López, courtesy of Architecture Project].

[Image: Photo by Luis Rodríguez López, courtesy of Architecture Project].

Another elevator post coming soon…

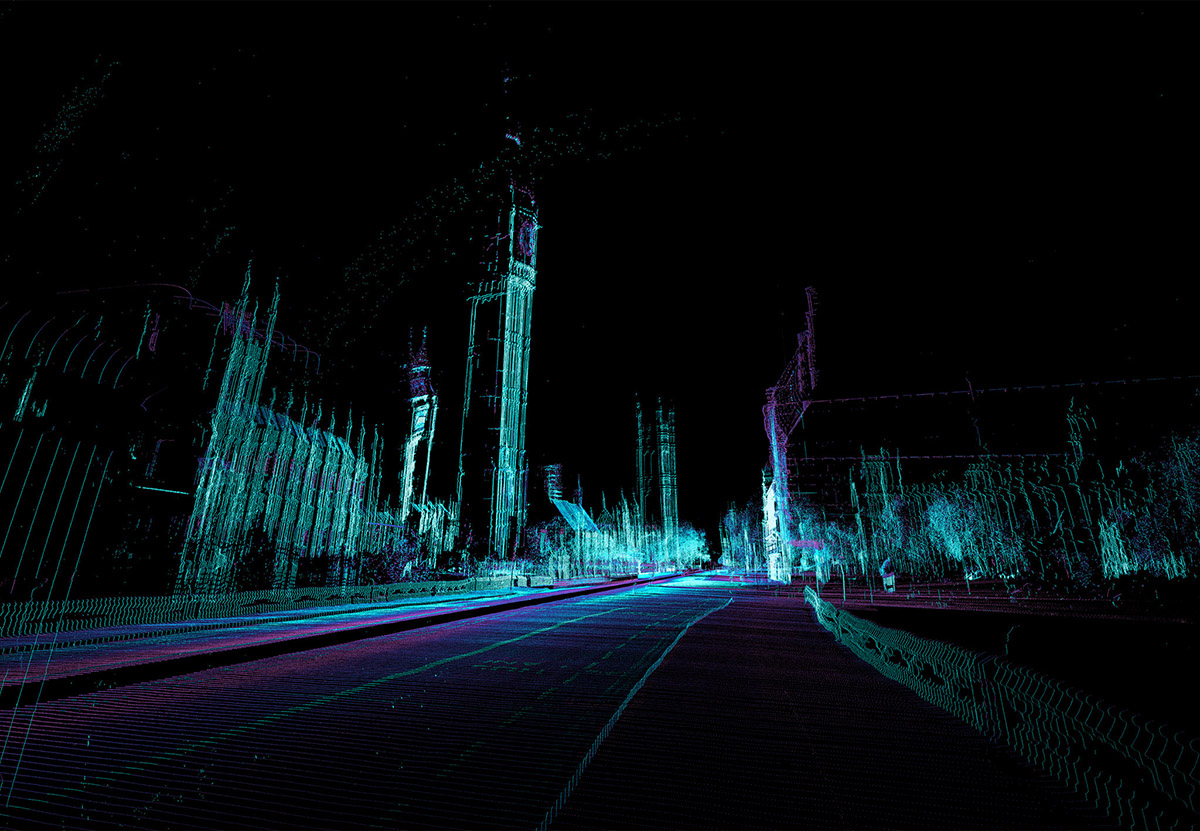

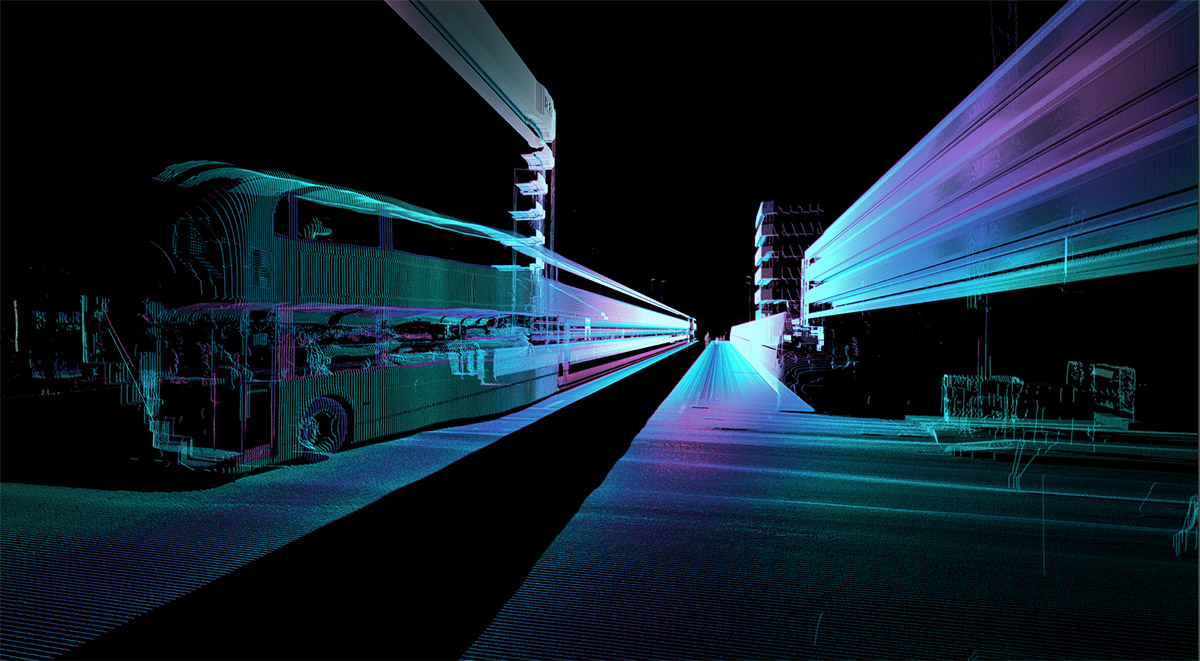

Computational Romanticism and the Dream Life of Driverless Cars

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

Understanding how driverless cars see the world also means understanding how they mis-see things: the duplications, glitches, and scanning errors that, precisely because of their deviation from human perception, suggest new ways of interacting with and experiencing the built environment.

Stepping into or through the scanners of autonomous vehicles in order to look back at the world from their perspective is the premise of a short feature I’ve written for this weekend’s edition of The New York Times Magazine.

For a new series of urban images, Matt Shaw and Will Trossell of ScanLAB Projects tuned, tweaked, and augmented a LiDAR unit—one of the many tools used by self-driving vehicles to navigate—and turned it instead into something of an artistic device for experimentally representing urban space.

The resulting shots show the streets, bridges, and landmarks of London transformed through glitches into “a landscape of aging monuments and ornate buildings, but also one haunted by duplications and digital ghosts”:

The city’s double-decker buses, scanned over and over again, become time-stretched into featureless mega-structures blocking whole streets at a time. Other buildings seem to repeat and stutter, a riot of Houses of Parliament jostling shoulder to shoulder with themselves in the distance. Workers setting out for a lunchtime stroll become spectral silhouettes popping up as aberrations on the edge of the image. Glass towers unravel into the sky like smoke. Trossell calls these “mad machine hallucinations,” as if he and Shaw had woken up some sort of Frankenstein’s monster asleep inside the automotive industry’s most advanced imaging technology.

Along the way I had the pleasure of speaking to Illah Nourbakhsh, a professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon and the author of Robot Futures, a book I previously featured here on the blog back in 2013. Nourbakhsh is impressively adept at generating potential narrative scenarios—speculative accidents, we might call them—in which technology might fail or be compromised, and his take on the various perceptual risks or interpretive short-comings posed by autonomous vehicle technology was fascinating.

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

Alas, only one example from our long conversation made it into the final article, but it is worth repeating. Nourbakhsh used “the metaphor of the perfect storm to describe an event so strange that no amount of programming or image-recognition technology can be expected to understand it”:

Imagine someone wearing a T-shirt with a STOP sign printed on it, he told me. “If they’re outside walking, and the sun is at just the right glare level, and there’s a mirrored truck stopped next to you, and the sun bounces off that truck and hits the guy so that you can’t see his face anymore—well, now your car just sees a stop sign. The chances of all that happening are diminishingly small—it’s very, very unlikely—but the problem is we will have millions of these cars. The very unlikely will happen all the time.”

The most interesting takeaway from this sort of scenario, however, is not that the technology is inherently flawed or limited, but that these momentary mirages and optical illusions are not, in fact, ephemeral: in a very straightforward, functional sense, they become a physical feature of the urban landscape because they exert spatial influences on the machines that (mis-)perceive them.

Nourbakhsh’s STOP sign might not “actually” be there—but it is actually there if it causes a self-driving car to stop.

Immaterial effects of machine vision become digitally material landmarks in the city, affecting traffic and influencing how machines safely operate. But, crucially, these are landmarks that remain invisible to human beings—and it is ScanLAB’s ultimate representational goal here to explore what it means to visualize them.

While, in the piece, I compare ScanLAB’s work to the heyday of European Romanticism—that ScanLAB are, in effect, documenting an encounter with sublime and inhuman landscapes that, here, are not remote mountain peaks but the engineered products of computation—writer Asher Kohn suggested on Twitter that, rather, it should be considered “Italian futurism made real,” with sweeping scenes of streets and buildings unraveling into space like digital smoke. It’s a great comparison, and worth developing at greater length.

For now, check out the full piece over at The New York Times Magazine: “The Dream Life of Driverless Cars.”

Occult Infrastructure and the “Funerary Teleportation Grid” of Greater London

Speaking of cracks in space-time, an urban legend I love is the one about a tomb in Brompton Cemetery, London, allegedly designed by Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi and rumored to be a time machine.

[Image: Via The Clerkenwell Kid].

[Image: Via The Clerkenwell Kid].

A sadly now-defunct blog called The Clerkenwell Kid is a great resource for this. There, we read that Bonomi “traded as an archaeological artist but is thought to have been a tomb raider”:

He is also generally considered to have been the designer of the Egyptian styled “Courtoy” tomb in Brompton cemetery which was ostensibly intended to be the final resting place of “three spinsters”. An interesting legend has grown up around this mausoleum because it is the only one in the cemetery for which there is no record of construction. This, together with Bonomi’s obsession with the afterlife (reflected in the hieroglyphs on the tomb), have been held by some to be evidence that it is not a tomb at all but a time machine and that the three spinsters, if they existed at all, were in fact his time travelling sponsors.

The correct question to ask here is not: is this true? Is this tomb really a time machine? The correct question to ask here is: how freaking cool is this?

The Clerkenwell Kid then goes one better, however, claiming that this urban legend is wrong—because it isn’t ambitious enough.

In fact, we’re told, the tomb was actually one of five such chambers, designed and constructed by Bonomi in an occult conspiracy with his colleague, Samuel Alfred Warner.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the British Museum].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the British Museum].

“Amongst several other inventions,” the Kid tells us, “Warner claimed to have developed a mysterious missile capable of destroying ships from a distance”:

The Royal Navy were convinced enough by his demonstrations to pay him to develop this new weaponry but proved unable to reproduce his results independently. This was because what Warner had allegedly discovered (with the help of ancient knowledge gained by Bonomi in Egypt) was an occult way of “teleporting” a bomb a short distance—I suppose you could call it a “psychic torpedo.”

Again, the interest for me here is not whether or not people actually were teleporting themselves—let alone submarine torpedoes!—back and forth through time using Egyptological monuments hidden in London cemeteries.

The interest for me, instead, is at least two-fold: one, how awesome a story this is, and how much I want to tell everyone about it, and, two, how urban infrastructure always seems to inspire, catalyze, or emblematically come to represent these sorts of unexpected narrative investments.

We could say it’s the paranoia of infrastructure: the belief that there is always a bigger story we don’t know, or that someone deliberately isn’t telling us, about how our cities came to be the way they are today. We see this in everything from the water-theft politics of Chinatown to the high-speed rail conspiracies of True Detective Season 2, to this teleportation chamber disguised in plain sight in Brompton Cemetery.

The fact that this story has an atmosphere of the occult only makes literal the notion that the real histories of our cities, the true tales of backstage deals, hidden interests, and untold corruption that made them what they are, have been purposefully obscured from us—they have been occulted—by mysterious figures who prefer we don’t know.

It’s as if narrative paranoia is the default note of infrastructural investigation.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the British Museum].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the British Museum].

In any case, The Clerkenwell Kid keeps upping the ante. Remember those five teleportation chambers? Well, there were actually seven!

In dark collaboration, this legend goes, Bonomi and Warner set about constructing “a transportation grid around London” that would “reduce the time taken to travel the large distances of the vast, congested metropolis. To this end they built seven Egyptian teleportation chambers in the most suitable places they could find—in each of the seven new cemeteries that had been built in the capital from 1839.”

The Kid has a great phrase for this, referring to it as “the London funerary teleportation grid.” Surrounding the city like a seven-pointed star, these tombs formed a kind of mortuarial diagram—an urban-scale morbid force-field—that could zap people back and forth through Greenwich space-time.

It’s worth pointing out, however, that the rumors continue, leaking beyond the borders of Old Blighty, to suggest that there is yet another such transportation monument—but it’s over the English Channel, in Paris.

Even within the complicated mythology of these urban legends, this Parisian tomb is an outlier, but it brings with it an interesting plot development. That is, under the cover of developing something like a primitive military radar system that could protect the English Channel from foreign invasion, occult architects and Egyptologists were actually bilking the defense establishment to amass funds and construct this teleportation grid, scattered throughout the war-shadowed cemeteries of western Europe.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the British Museum].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the British Museum].

Now all we need to do is uncover an undocumented Egyptian tomb somewhere in a rainy Swiss mountain churchyard or in the fog-shrouded hills outside Turin, perhaps designed by a bastard child of Bonomi, and we can help keep this urban legend alive…

Until then, for more information check out these three posts over at The Clerkenwell Kid.

Subterranean Saxophony

[Image: Photo by Steve Stills, courtesy of the Guardian].

[Image: Photo by Steve Stills, courtesy of the Guardian].

Over in London later today, the Guardian explains, composer Iain Chambers will premiere a new piece of music written for an unusual urban venue: “the caverns that contain the counterweights of [London’s Tower Bridge] when it’s raised.”

The space itself has “the acoustics of a small cathedral,” Sinclair told the newspaper, citing John Cage as an influence and urging readers “to listen to environmental sounds and treat them as music,” whether it’s the rumble of a bridge being raised or the sounds of boats on the river.

In fact, Chambers will be performing one of Cage’s pieces during the show tonight—but, alas, I suspect it is not this one:

It is rumored that the final, dying words of composer John Cage were: “Make sure they play my London piece… You have to hear my London piece…” He was referring, many now believe, to a piece written for the subterranean saxophony of London’s sewers.

Read much more at the Guardian—or, even better, stop by tonight for a live performance.

(Spotted via @nicolatwilley).

Water & Power

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

While going through a bunch of old photos of Los Angeles on the Library of Congress website for a project I’m doing at USC this year, I was amazed by these interior shots of the F. E. Weymouth Filtration Plant at 700 North Moreno Avenue in L.A.

Despite being designed for the administration of an urban water-processing site, the interiors seem to play with some strange, Blade Runner-like variation on Byzantine modernism, where federalist detailing meets a hydrological Babylon.

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

As the open plan interior of a contemporary home, this place would almost undoubtedly show up on every design website today—imagine a better railing on the central staircase, a galley kitchen on one side, a bed lit by retro-styled fluorescent tubes at the far end, some bold moments of color—but it’s just a piece of everyday municipal infrastructure.

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

In any case, continuing the vaguely sci-fi feel, there is even a tiled fountain—a Mediterranean concession to the building’s role in water filtration—on one wall, emphasized by these amazing lighting features, yet it looks more like a film set, both ancient and futuristic.

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

[Image: Via the Library of Congress].

Alas, I’m not a huge fan of the exterior, although it is, in fact, a fairly amazing example of municipal design gone more sacred than profane. But an equally streamlined modernism in keeping with those interiors would have made this place totally otherworldly.

[Image: From the Library of Congress].

[Image: From the Library of Congress].

Finally, the marbled lobbies continue the surreal mix-up of styles, eras, and materials with something that could perhaps be described as Aztec corporatism with its huge graphic seal and other geometric motifs.

[Image: From the Library of Congress].

[Image: From the Library of Congress].

For shots of the actual waterworks, click through to the Library of Congress.