[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via Landscape Architecture Magazine].

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via Landscape Architecture Magazine].

Not all the news coming out of Milwaukee involves misguided highway megaprojects or tax-funded crony capitalism—though there is that.

For example, Wisconsin governor Scott Walker—confusing an earlier generation’s urban mistakes with how a city is meant to function—has been plowing billions of dollars’ worth of taxpayer money into “freeway megaprojects” for which “the pricetag got so big that leaders from his own party rejected his plan as fiscally irresponsible, leaving the state budget in limbo,” Politico reports:

As the state has shifted resources into freeway megaprojects, 71 percent of [Wisconsin’s] roads are in mediocre or poor condition, according to federal data. Fourteen percent of its bridges are structurally deficient or functionally obsolete, which is actually better than the national average. Walker and his fellow Republicans have killed plans for light rail, commuter rail, high-speed rail, and dedicated bus lanes on major highways, so there is almost no public transportation connecting Milwaukee to its suburbs, intensifying divisions in one of the nation’s most racially, economically and politically segregated metropolitan areas. Yet Walker, who is running for president as a staunch fiscal conservative, has pushed a $250 million-per-mile plan to widen Interstate 94 between the Marquette and the Zoo despite fierce local opposition.

If that sounds both avoidable and unfortunate, consider the fact that “Walker also killed a ‘Complete Streets’ program that pushed road builders to accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians.”

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via Politico].

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via Politico].

At the same time, Walker has also “championed a high-profile proposal to spend a quarter of a billion dollars of taxpayer money to help finance a new Milwaukee Bucks arena—all while pushing to slash roughly the same amount from state funding for higher education,” the International Business Times reports.

But, hey, why does Wisconsin need universities when everyone can just go to an NBA game? Not that benefitting the public is even Walker’s goal: “One of those who stands to benefit from the controversial initiative is a longtime Walker donor and Republican financier who has just been appointed by the governor to head his presidential fundraising operation.”

In any case, an interesting landscape test-project is currently underway in Milwaukee, called the “BaseTern” program.

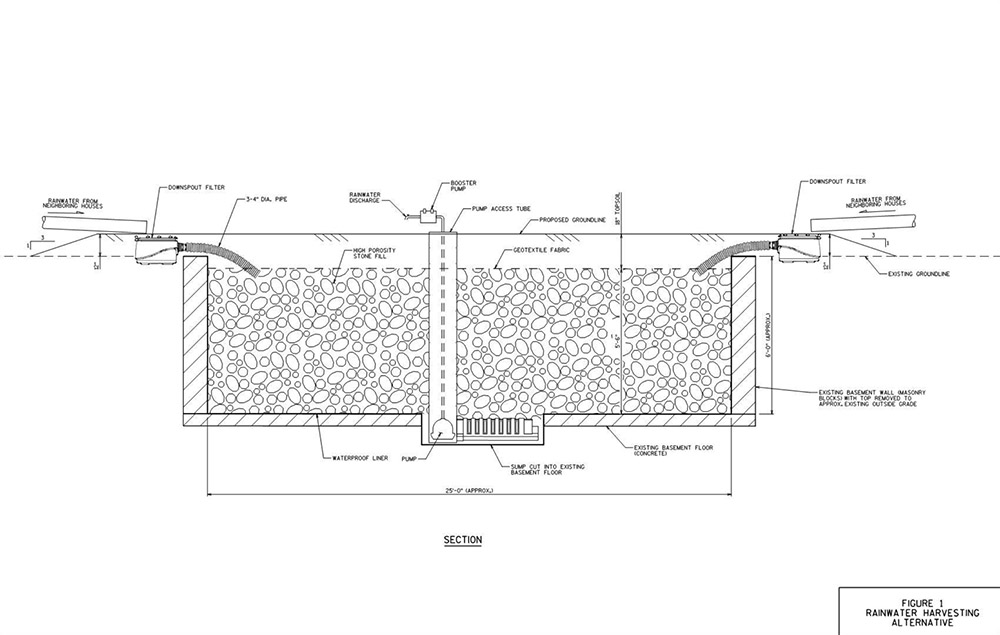

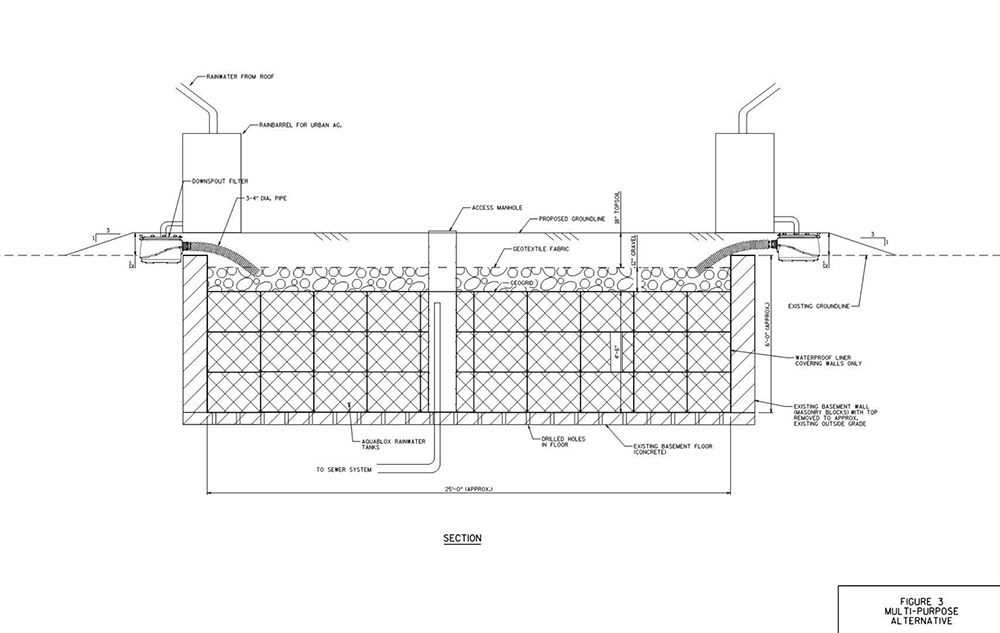

As the city explains it, a “BaseTern” is “an underground stormwater management or rainwater harvesting structure created from the former basement of an abandoned home that has been slated for demolition.” Why is the city doing this?

By using abandoned basements, the City saves the cost of demolition on these structures (filing the basement and grading the surface) and on excavation for the new structure. In addition, BaseTerns provide significant stormwater storage capacity on a single site, the equivalent of up to 600 rain barrels.

The result, the city is keen to add, is “not an open pit. Rather a BaseTern is a covered structure, which is covered with topsoil and grass, and will appear the same as conventional vacant lot.”

In their July 2015 issue, Landscape Architecture Magazine explained that this is, in fact, “the world’s first such system.” Conceived—and actually trademarked—by a city official named Erick Shambarger, the idea was inspired by a GIS-fueled discovery that the worst flooding in the city always “occurred in neighborhoods with high rates of foreclosures. The city controls roughly 900 foreclosed properties, many of which it plans to demolish. Shambarger figured the city could preserve the basement structure and put it to use.”

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “Vacant Basements for Stormwater Management Feasibility Study“].

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “Vacant Basements for Stormwater Management Feasibility Study“].

While there is something metaphorically unsettling in the idea that parts of a blighted, financially underwater neighborhood might soon literally be underwater—transformed into a kind of urban sponge for the rest of Milwaukee—the notion that the city can discover in its own economic misfortune a possible new engineering approach for dealing with seasonal flooding and super-storms is an inspiring thing to see.

The BaseTern program also potentially suggests a stopgap measure for coastal cities set to face rising sea levels well within the lifetimes of the coming generation.

In the all but inevitable managed retreat from the coast that seems set to kick off both en masse and in earnest by midcentury—something that is already happening in New York City, post-Sandy—perhaps the subterranean ruins of old neighborhoods left behind can be temporarily repurposed as minor additions to a broader coastal program intent on reducing flooding for residents further inland.

Before, of course, those underground voids—former guest bedrooms, dens, man caves, she sheds, and basements—are inundated for good.

Read more about BaseTerns over at Landscape Architecture Magazine.

As a civil engineer, I think BaseTern is a good concept; however I feel calling it "worlds first" is a bit of an exaggeration. The term BaseTern, might be world first, but every other aspect I am sure has been done by someone, somewhere. I know for certain that the idea of an underground storage formed by using the voids in stone fill is used widely in Christchurch, New Zealand. Forming storage with plastic crates is also fairly common, and many manufacturers around the place manufacture them. Similarly there is nothing new, unique or world first about using pumps to drain a storage volume. I would be surprised if no one has never used an old basement for the walls of the basin.

Geoff, I see your point about using low-income neighborhoods as sponges for wealthier areas, but I don't think that's what's going on here. These neighborhoods already are underwater — financially and literally. Converting one lot into a cistern makes that property the sponge for the rest of the immediate neighborhood. I also asked the city whether replacing a home with a cistern would backfire later and disincentivize future reinvestment. They didn't think so, since you don't need many to make an impact (plus, a BaseTern could be designed as public green space, which also is typically lacking in economically disadvantaged communities).