I haven’t done one of these in a long, long time… Here are twenty-seven new or recent books, ranging from true crime to science fiction, architecture to media theory, for your back-to-school or end-of-summer reading pleasure.

* * *

1) The Cartel by Don Winslow (Alfred A. Knopf)

The Cartel is technically a sequel to The Power of the Dog, but the storyline stands on its own even without prior knowledge of the characters. Here, DEA agent Art Keller must track down—again—a man named Adán Barrera, the leader of a notorious Mexican drug cartel, an organization whose sheer brutality and unsettling ubiquitousness author Don Winslow does not shy away from depicting.

What will probably interest BLDGBLOG readers—in addition to the incredible coincidence of The Cartel‘s publication during the same week that drug lord “Chapo” Guzmán escaped from his prison in Mexico—is Winslow’s exploration of the cartel itself as a self-contained political structure, a kind of sovereignty without borders, operating through a combination of violence and logistics, with few limitations, all over the world.

I had the pleasure of seeing Winslow speak at an event last month at Bookcourt in Brooklyn, where his descriptions of cartel activities offered a kind of diagonal perspective on their operations. Winslow memorably pointed out how farmers in the Sinaloa region of Mexico had been swept up into the cartel’s infinitely flexible method of production, and that, despite any ensuing role growing and harvesting marijuana or even poppies, the cartel offered them new jobs in logistics, not agriculture. “They didn’t want to be farmers,” Winslow said at Bookcourt, “they wanted to be FedEx.”

2) ZeroZeroZero by Roberto Saviano, trans. Virginia Jewiss (Penguin)

Roberto Saviano’s Gomorrah is something of a modern classic in terms of its documentation of organized crime in Italy. A fantastic book, Gomorrah depicts what is, in essence, a parallel state operating side by side with the Italian government. In the process, Saviano’s reporting suggests that sufficiently organized criminal activity is all but indistinguishable from a nation-state, even taking on the tasks of waste disposal, transportation, and de facto taxation, with a tragic aura of incompetence and corruption.

ZeroZeroZero pairs well with Winslow’s novel, as it offers the drug trade as a prism or lens through which to see the world. This is the book’s very premise: “Look at cocaine and all you see is powder,” the cover says. “Look through cocaine and you see the world.” Saviano begins his nested stories of the modern drug trade with an unnamed police officer in New York City, but soon follows cocaine’s narcotic tentacles around the world, from Miami to Colombia, Sinaloa to Spain, by way of drug-smuggling submarines and cargo ships, AK-47s and bullet-proof cars.

As with Winslow’s novel, the interest of the book is not only in getting a glimpse of this stranger, much darker world existing alongside or beneath ours; it’s in the fact that this world has such very real territory, with brute-force powers rivaling municipal governments and nation-states, and that the more intensely authorities might try to stomp it out, the larger and more sinister it grows.

3) Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War by Peter Singer and August Cole (Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

I’ve followed Peter Singer’s work with great interest for nearly a decade now, ever since the publication of his book Corporate Warriors, and I was thus intrigued to see that he and fellow war technology theorist August Cole had teamed up to write a novel. While Ghost Fleet is not a book to pick up if you are looking for strong character development, it is exactly the book to pick up if you want to see how a decade’s worth of research into new or speculative military technologies can be assimilated and compiled into a work of near-future fiction.

The basic plot of Ghost Fleet is that a non-nuclear naval and cyber world war has broken out between the United States and China, its battlefields ranging from Hawaii and the broader Pacific to the anti-gravitational heights of near-Earth orbit. I got to see Singer and Cole both speak last month at New America NYC, where they discussed the novel’s depiction of multinational corporations in a future theater of war; the prospect of weaponized logistics chains; whose side our new class of billionaires might take in a global conflict; and even the fate of sovereignty in Greenland. Both authors have pointed out in interviews that they hoped to write the Red Storm Rising of our time: a kind of geopolitical beach read.

Cleverly, the book includes hundreds of footnotes and citations for all of its references to things such as railguns, microdrones, adaptive camouflage, satellite warfare, nuclear submarine detection, and more; this has the effect of making Ghost Fleet feel like reading a more exciting, distorted-mirror version of the daily news and—even better—it has the reverse effect of making the daily news feel like an outtake from Ghost Fleet.

4) Future Crimes by Marc Goodman (Doubleday)

Ghost Fleet pairs very well with Marc Goodman’s excellent, highly recommended book Future Crimes. Goodman’s book should be required reading for anyone using the internet today, let alone anyone interested in the dark side of technological innovation. Expect to learn more about GPS hacking, “burglary 2.0,” mass identity theft, online drug markets, even assassination via medical prosthetics.

5) Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson (Orbit)

Long-time readers of BLDGBLOG might remember my interview with novelist Kim Stanley Robinson, in which Robinson talked about offworld utopias, the politics of sustainability, the future of California, and more. Robinson is back with Aurora, a new novel about a massively intergenerational group of human explorer-refugees, passengers aboard a semi-sentient interstellar ship headed toward a distant planet where human life might be sustainable.

The book is not optimistic. Its portrayal of characters driven half-mad with desperation and a realization of doom, of a planet and its crypto-ecosystem that seems intent on rejecting the colonists, and of an on-board computer system that eventually wakes up into full narrative consciousness does not reveal confidence that humans will ever find another planet to call home.

6) The Meaning of Liberty Beyond Earth edited by Charles S. Cockell (Springer)

This makes for an odder pairing than the previous ones, but Charles S. Cockell’s edited volume on The Meaning of Liberty Beyond Earth is an interesting companion to set alongside much of contemporary science fiction (including, I should note, Ghost Fleet).

Described as a book that “takes the discussion of liberty into the extraterrestrial environment,” it includes papers on offworld sovereignty, what territory means in space, private corporate enterprise as a possible model for future space-states, and the governmental bodies or institutions that might serve to regulate this emerging sphere. From the book:

As more national governments develop expansive space programmes and more private companies design and build spaceships with the capacity to launch satellites, robots and humans into space, the number of organisations in space is growing. With this expansion comes the inevitable consequence of an expanding number of interests to protect and so with that, the chance for a clash of ownership, rules and regulations which together define the environment for individual freedom.

The The Meaning of Liberty Beyond Earth includes two pieces authored or co-authored by scifi novelist Stephen Baxter.

7) The Conflict Shoreline: Colonialism as Climate Change in the Negev Desert by Eyal Weizman and Fazal Sheikh (Cabinet Books)

Inspired by aerial images of the Negev Desert taken by photographer Fazal Sheikh, architect and forensic historian Eyal Weizman wanted to understand something that Sheikh had documented: the ghostly remains of old villages, communal graveyards, and farm houses that could be seen in the ground, almost but not quite erased from the landscape, yet that also did not appear on official Israeli state maps.

This led Weizman to write what is, in effect, an extended essay on the role of agriculture, state archival policies, regional maps, desertification, and climate change in a politically motivated attempt to remove from the landscape any trace of pre-Israeli settlement. As Sheikh’s photos showed, what appears to be bare desert—an inhospitable wasteland outside of human civilization—reveals, when seen from above, the structural outlines of earlier inhabitants.

Together with archaeological evidence, old land deeds, and British military surveillance photos from WWI, this has led to court cases over land ownership and even citizenship. One such court case—a man named Nuri Al-‘Uqbi suing for recognition of his family’s land claim—forms the narrative and legal backbone of Weizman’s essay.

8) KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps by Nikolaus Wachsmann (FSG)

Nikolaus Wachsmann’s KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps is a history of the concentration camps, but as organizational entities, where administration itself becomes a source of dehumanization and brutality. Wachsmann shows how the camp system grew from an archipelago of smaller units to the international scale of the Holocaust, with camps operating throughout Europe, their functions—from daily work schedules to mass executions—systematized and closely reported. There was ultimately no shortage of documentation, despite efforts to destroy records or downplay the system’s horrific extent, and the book itself includes some 200 pages of notes, sources, and appendices.

9) Brodsky & Utkin by Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (Princeton Architectural Press)

The “paper architecture” of Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin has been reprinted in a new edition by Princeton Architectural Press. Flooded cities of pillars, glass towers, arching landforms across sprawling supergrids, infinite rooms repeated across pyramids, domes, and antenna-covered housing blocks, they are equal parts Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Modernist allegory, and Soviet bloc existentialism, their projects are as much psychological fables as they are architectural proposals.

[Image: From Brodsky & Utkin by Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (Princeton Architectural Press)].

[Image: From Brodsky & Utkin by Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin (Princeton Architectural Press)].

10) African Modernism: The Architecture of Independence—Ghana, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Zambia edited by Manuel Herz et al. with photographs by Iwan Baan and Alexia Webster (Park Books)

Manuel Herz has quietly made a name for himself studying, in admirably granular detail, architectural design and production in Africa, whether that means looking at the spatial effects of migration in Nairobi, Kenya, or the complex interplay between formal and informal settlement practices in the refugee camps of Western Africa, as in his excellent book From Camp to City.

African Modernism is a massive book—it is nearly 700 pages in length and more than a foot tall—that takes as its focus post-independence urban design and architecture in Ghana, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Zambia. As Herz writes in his introductory essay, “In our general perception the African continent stands for suffering and misery. It also remains a mystery as its histories, cultures, traditions, languages, politics and economies remain outside of our framework of reference. The continent is usually seen as a single entity without differentiation and without consideration of its fifty-four countries and the vast differences among its gigantic territory and diverse cultures.”

The resulting project is thus an attempt to address this strange blindness toward African urbanism, cataloging and—at least through publication—helping to preserve buildings all but never documented in contemporary architectural publications. Finally, there is also a political goal, which is to place Modern architecture in its appropriate historical context, “looking at the conscious and deliberate role architecture played in the formation of national states, with all the contradictions, dilemmas and problems this implies.”

11) War Plan Red: The United States’ Secret Plan to Invade Canada and Canada’s Secret Plan to Invade the United States by Kevin Lippert (Princeton Architectural Press)

While, at first glance, the story told in Kevin Lippert’s War Plan Red seems like what might happen if someone rewrote Dr. Strangelove as an episode of South Park, the mutual invasion plans it details between the United States and Canada comes with a dark humor that veers more toward tragedy. That two democracies with a shared 4,000-mile land border would go through the trouble of cooking up elaborately farcical battle strategies for partially consuming one another’s border states says a lot about the militarized distrust and paranoia that scripted the Cold War. Lippert’s book includes the actual war plans, as well as their historical context.

To a certain extent, this pairs well with another title from Princeton Architectural Press, Tom Vanderbilt’s engaging Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America (republished a few years ago in a paperback edition from the University of Chicago Press).

12) Equilateral by Ken Kalfus (Bloomsbury)

The plot of Equilateral is seemingly tailor-made for BLDGBLOG readers: a fever-wracked British astronomer at the height of 19th-century colonialism forces tens of thousands of Egyptians to build an enormous equilateral triangle in the Sahara Desert. Its explicit design goal is to be so big that the resulting figure, when set aflame with gasoline, will be visible from Mars. Indeed, the astronomer’s goal is to communicate, through Pythagorean geometry, with the intelligent beings he believes to exist on the Red Planet, and to do so even while he can barely speak with—and arrogantly refuses to recognize intelligence in—the Egyptian workers he has all but enslaved to build this misguided megastructure.

Incredibly, this story was inspired by a real-life plan devised by a man named Joseph Johann von Littrow, to build a flaming geometric sign in the Sahara as a means of communicating with other planets.

Kalfus does an excellent job mocking the racist overtones of the astronomer’s project without becoming didactic or politically heavy-handed, and he even allows moments of genuine wonder into the text, as the possibility of extraplanetary intelligence is debated amongst the novel’s European intelligentsia. It probably goes without saying that all does not end well for the equilateral triangle, a kind of 19th-century SETI project in the desert.

13) Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (Vintage)

The end of the world has never been so hot. Whether it’s The Walking Dead, The Hunger Games, or Peter Heller’s recent, great book The Dog Stars, watching things fall apart is now a billion-dollar industry. As that intro might indicate, I went into Station Eleven with a healthy dose of skepticism, but ended up reading the whole thing in one sitting.

Far from a work of popular survivalist fiction, its end-times narrative is often only lightly applied. Against the backdrop of a near-universally fatal flu outbreak, author Emily St. John Mandel instead focuses her attention not on fire and apocalypse—although there are the requisite ruined airports and scenes set on the feral edges of a depopulated Toronto—but rather on the lives of a core group of characters whose goals, relationships, and interpersonal conflicts are left abruptly unresolved when the disease begins to spread.

The book thus has a disarmingly quiet air of reflective melancholy, enlivened by voluminous flashbacks to the characters’ pre-flu days, as it moves inevitably forward with a sense that, no matter how much we might believe otherwise, we all live amidst unfinished business. We will all have decisions to regret—and people to miss—when the end of things finally arrives.

14) Consumed by David Cronenberg (Scribner)

Legendary film director David Cronenberg has tried his hand at literary fiction—or, more accurately, at a genre-crossing murder mystery that owes much to William Gibson, Alfred Hitchcock, and Cronenberg’s own film work. The plot of Consumed involves a North Korean kidnapping plot, avant-garde filmmakers, bizarre sexual practices, anthropological fieldwork as reconceived in an age of VICE, and a grotesque use of 3D printers that many of today’s “design fiction” aficionados should find both creatively macabre and technically compelling.

15) Fourth of July Creek by Smith Henderson (Ecco)

I was drawn to Fourth of July Creek almost entirely on the strength and enthusiasm of a blurb from novelist Jeff VanderMeer, and I was glad to have followed his advice. While the bulk of the novel falls outside what I might call BLDGBLOG territory, its Cormac McCarthy-like exploration of off-the-grid survivalists in the vast National Forests of the U.S. is in fitting with this site’s interest in human beings forced to negotiate, and establish the barest toeholds of religious belief or culture, in the face of extreme environments.

One particularly haunting scene involves the eruption of Mount St. Helens and a hardcore survivalist who, isolated away from media in his forest homestead, is convinced the horrible, blinding rain of ash and fire is actually the opening salvo of a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union.

16) Crooked by Austin Grossman (Mulholland Books)

Crooked could be thought of as Mike Mignola’s B.P.R.D. transplanted into the heart of 20th-century U.S. presidential history, with Richard Milhous Nixon presented as a not necessarily willing participant in the battle of ancient magic normally referred to as the Cold War. Of course, if the B.P.R.D. reference doesn’t do anything for you, just imagine H.P. Lovecraft re-writing the history of the Watergate break-in, and you can begin to picture what unfolds in Austin Grossman’s novel.

While I agree with other critics that too much action occurs off-stage—gigantic creatures emerge from the snow-covered forests of eastern Russia, but only in whispered reports Nixon receives from White House aides—it’s nonetheless an enjoyably nuts and well-written book that takes occult conspiracy theories about U.S. governmental power and turns them up to eleven.

17) Inside the Machine: Art and Invention in the Electronic Age by Megan Prelinger (W.W. Norton)

Inside the Machine is about what author Megan Prelinger calls “the enormous electronic infrastructures and networks that shape our world today [yet] remain hidden from our sight.” More than that, though, Prelinger looks at the ads, artworks, and cinematic representations that helped 20th-century popular culture visualize the world of the electron. Human nervous systems, player pianos, printable circuit boards, Cold War radar systems, and even an “unsettlingly alert” 1950s thinking machine called “the Perceptron,” all come together with full-color reproductions of amazing, often inadvertently amusing period art.

18) Rust: The Longest War by Jonathan Waldman (Simon & Schuster)

Rust, Jonathan Waldman’s long look at the material effects of corrosion, strongly bears the literary influence of John McPhee. From innovations in canned foods to the super-sized national campaign to preserve—and more or less entirely rebuild—the Statue of Liberty, Waldman uses the threat of corrosion as something more like a psychological metaphor for the people he profiles, including industrial consultants and art photographers (with an unexpected dose of LeVar Burton thrown in for good measure).

19) Soldier Girls: The Battles of Three Women at Home and at War by Helen Thorpe (Scribner)

As Helen Thorpe wrote in a recent op-ed for The New York Times, “Women are the fastest growing group of veterans treated by the V.A., and projections show that women will make up over 16 percent of the country’s veterans by midcentury.” Her new book Soldier Girls looks at three women from very different personal and political backgrounds both during their times of military service and after. The result is an excellent look at the under-documented experiences of women in the U.S. military, including the physical risks and gendered stereotypes they all but constantly and frustratingly face.

20) Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest by Carl Hoffman (William Morrow)

If you’ve ever visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art and stared in awe at the incredible collection of objects from Oceania, Carl Hoffman’s Savage Harvest fills in the necessary backstory for understanding how those works got there. It was not just a story of underpaid local artisans—although it was this. It was a story of cultural misunderstanding and, ultimately, cannibalism, as collector Michael Rockefeller, son of the New York State governor and scion of the wealthiest families in the world, failed to understand the remote and extremely isolated island world he, in retrospect, blindly stumbled into.

Author Carl Hoffman front-loads the book with a gruesome scene of cannibalism, but its shock dissipates as the book shifts focus to tell the larger story, even more tragic story of a tribe knocked about from confrontation to confrontation by an ever-increasing onslaught of globalized outsiders who made little effort to understand the tightly organized world their presence so violently interrupted.

21) St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street by Ada Calhoun (W.W. Norton)

Ada Calhoun’s book about “America’s hippest street” is due out later this fall. It describes the long transformation of a legendary East Village street, from its earliest days as part of the Stuyvesant family farm to a maze of booze-smuggling tunnels in the age of Prohibition, and from a smoke-hazed world of Beat cafes and punk rock bars to the depressing smear of Chipotle wrappers, European tourists, and ill-considered tramp stamps that it is today. The book’s interest is not in its condemnation of the new St. Mark’s, however, but in the deep history of a single street that Calhoun has managed to shape from long walks through the city’s past.

22) The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media by John Durham Peters (University of Chicago Press)

John Durham Peters asks whether animals, too, have media—or even are media, their bodies communicative vessels relaying and interpreting information through the basic elements of sea, fire, earth, and air. I first came across The Marvelous Clouds through an interview Peters did with the Los Angeles Review of Books, which is worth reading before embarking upon the book itself.

The latter is not strictly speaking a work of media theory or of natural history, but an inspired combination of the two—however, it is also very much an academic work. What I mean by that is simply that I have become so used to reading journalistic nonfiction these days that I kept waiting for Peters to go out into the field, boarding a boat with marine biologists or visiting an avian research lab for some intriguing character studies and a scene of reflective first-person experience; instead, he stays on campus, quoting Immanuel Kant and Martin Heidegger.

This could very well only be a problem when seen through the lens of my own particular expectations, of course; but I do genuinely long for more academic theoretical writing that is not afraid of becoming expeditionary, so to speak, testing its hypotheses not by quoting things you’ve probably already read in grad school but by introducing readers to relevant new worlds they are otherwise unlikely to visit.

Or, to put this another way: get John Durham Peters aboard a deepsea submarine somewhere, pinging abyssal plains or peering up through echoes at thinning polar ice caps, or drop him off in the canopy of a rain forest research station, studying pheromonal discourse networks sensible only to insects; add some Friedrich Kittler and I would read that book in a heartbeat.

23) TechGnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information by Erik Davis (North Atlantic Books)

This 2015 reprint of Erik Davis‘s cult classic TechGnosis comes with the refreshing realization that his work is more relevant today, not less. A startling and altogether off-kilter look at esoteric religious beliefs, vernacular folklore, what Davis calls “gnostic science fictions,” and today’s digital technology, it’s something like a bolt of lightning across the sky of today’s tedious tech writing, a world of circular reporting more concerned with product reviews than in discussing why technology exists—and what it’s doing to us—in the first place.

As the book’s own description explains, TechGnosis “uncovers startling connections between such seemingly disparate topics as electricity and alchemy; online roleplaying games and religious and occult practices; virtual reality and gnostic mythology; programming languages and Kabbalah. The final chapters address the apocalyptic dreams that haunt technology, providing vital historical context as well as new ways to think about a future defined by the mutant intermingling of mind and machine, nightmare and fantasy,” and, despite its (deliberately?) dated cover re-design, the book, originally published back in 1998, still feels fresh.

24) Vision Anew: The Lens and Screen Arts edited by Adam Bell and Charles H. Traub (University of California Press)

Vision Anew tries to assess what is happening to photography—not just technically but also historically and metaphorically—as the technology through which it operates rapidly shifts to digital. It is moving from chemistry to data, we might say. An edited compilation—co-edited by an old friend of mine from high school, in fact—it includes an all-star list of writers, from Walter Murch to Trevor Paglen, Rebecca Solnit to Ai Weiwei and László Moholy-Nagy.

25) Combat-Ready Kitchen: How the U.S. Military Shapes the Way You Eat by Anastacia Marx de Salcedo (Current)

I originally spotted this book after my wife reviewed it for Popular Science, where she describes Combat-Ready Kitchen as a look at how “the needs of the military play an outsized role in shaping the food industry’s research agenda, resulting in the proliferation of products that are optimized for portability, convenience, shelf-life, and mass appeal, rather than health, taste, or environmental sustainability.”

As the book’s subtitle also makes clear, author Anastacia Marx de Salcedo hopes to reveal how the needs and expectations of military R&D continually trump other health concerns or even public interest when it comes to food science and product development in the United States. More interestingly, though, Marx de Salcedo shows that everyday food products such as Cheetos and granola bars have military origins, as if the battlefields of the 20th and 21st centuries extend even to our supermarket shelves and our dinner plates.

26) Drone by Adam Rothstein (Bloomsbury)

27) Waste by Brian Thill (Bloomsbury)

The new series Object Lessons from Bloomsbury is an inspired one. It is also ambitious: with twenty-six titles and counting, each small book takes one object and dissects it relentlessly, revealing the constellation of economic forces and historical interests that have caused it to exist. The titles I’ve included here—Drone and Waste—are only two of the ones I’d suspect have the most interest for readers of this site, but forthcoming looks at the Shopping Mall, the Doorknob, and the Phone Booth, among others, all look promising.

Drone—for which I also supplied a back-cover blurb—is simultaneously a concise and a refreshingly widescreen look at autonomous machine systems and uncrewed aircraft, detailing not just their military role today but their algorithmic and even philosophical origins. The drone is now a ubiquitous, near-mythological presence in contemporary society, but author Adam Rothstein takes a step back from current events to ask, in a sense, what do drones want?

Meanwhile, Waste is as much an anthropology of excess production—or what it means to have so much stuff that vast quantities of it can be reclassified as without practical use, or as waste—as it is a look at the cultural, environmental, and landscape-scale effects of easily discarded materials.

* * *

All

Books Received:

August 2015,

September 2013,

December 2012,

June 2012,

December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”),

May 2010,

May 2009, and

March 2009.

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image by

[Image by  [Image by

[Image by

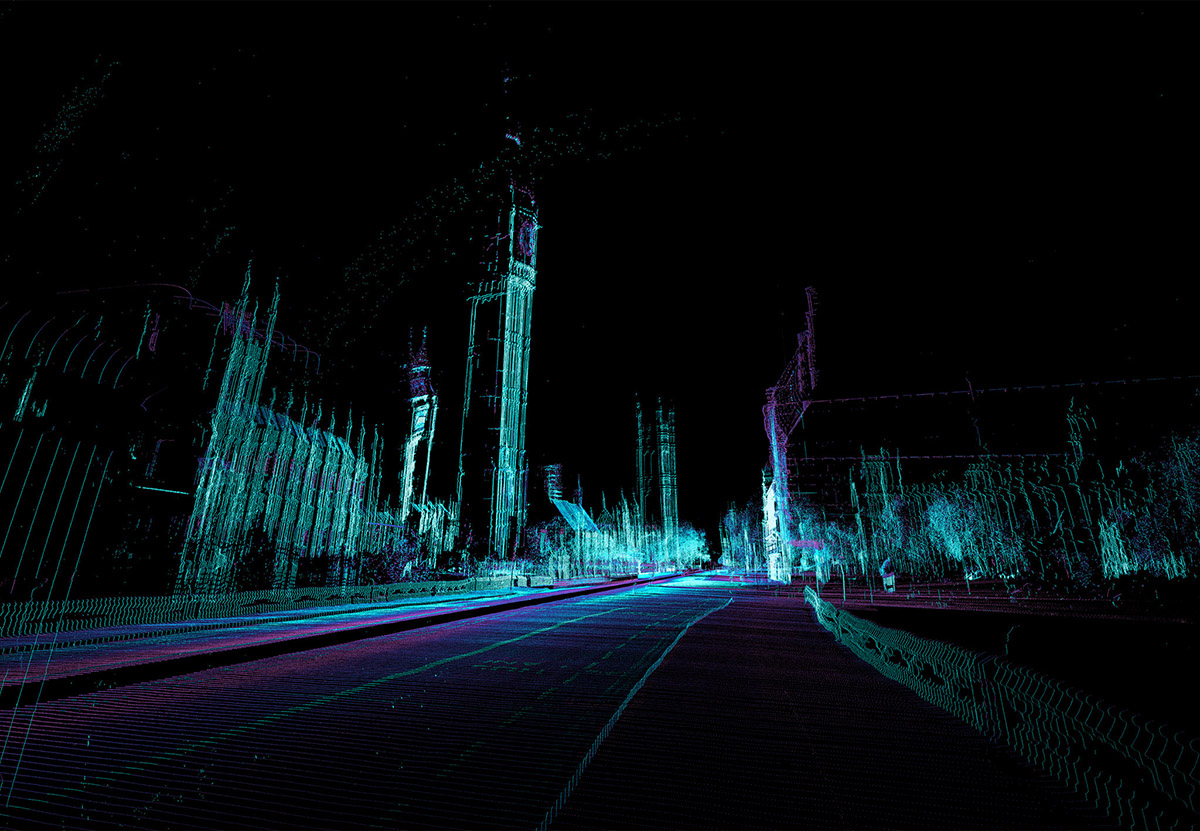

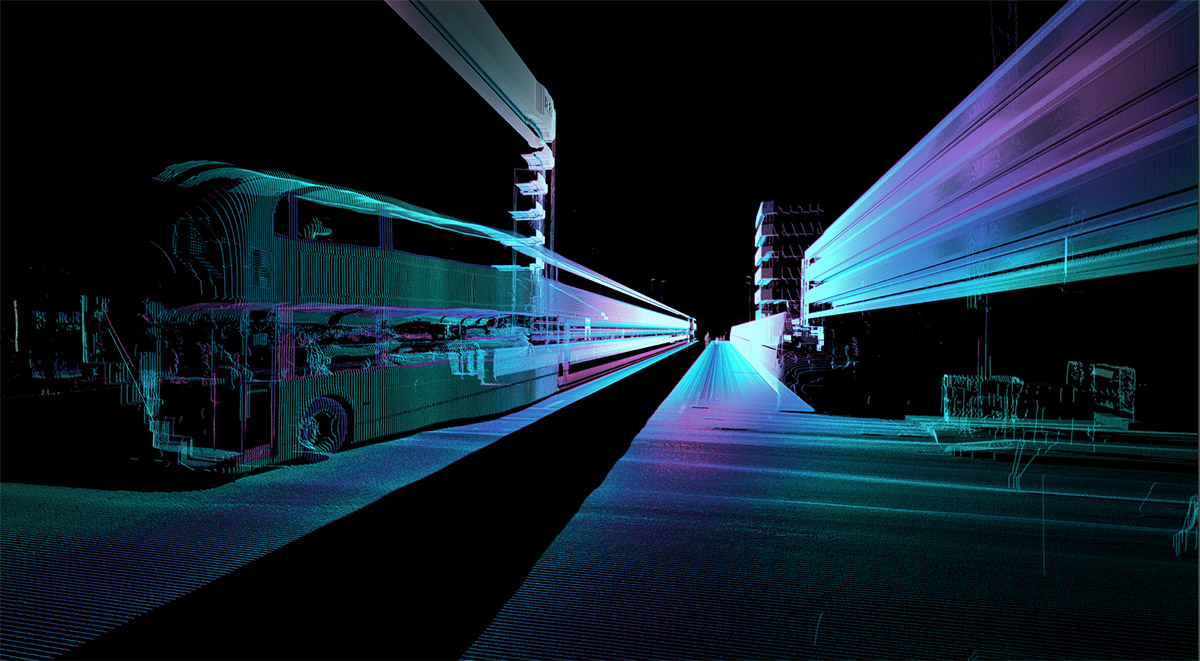

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

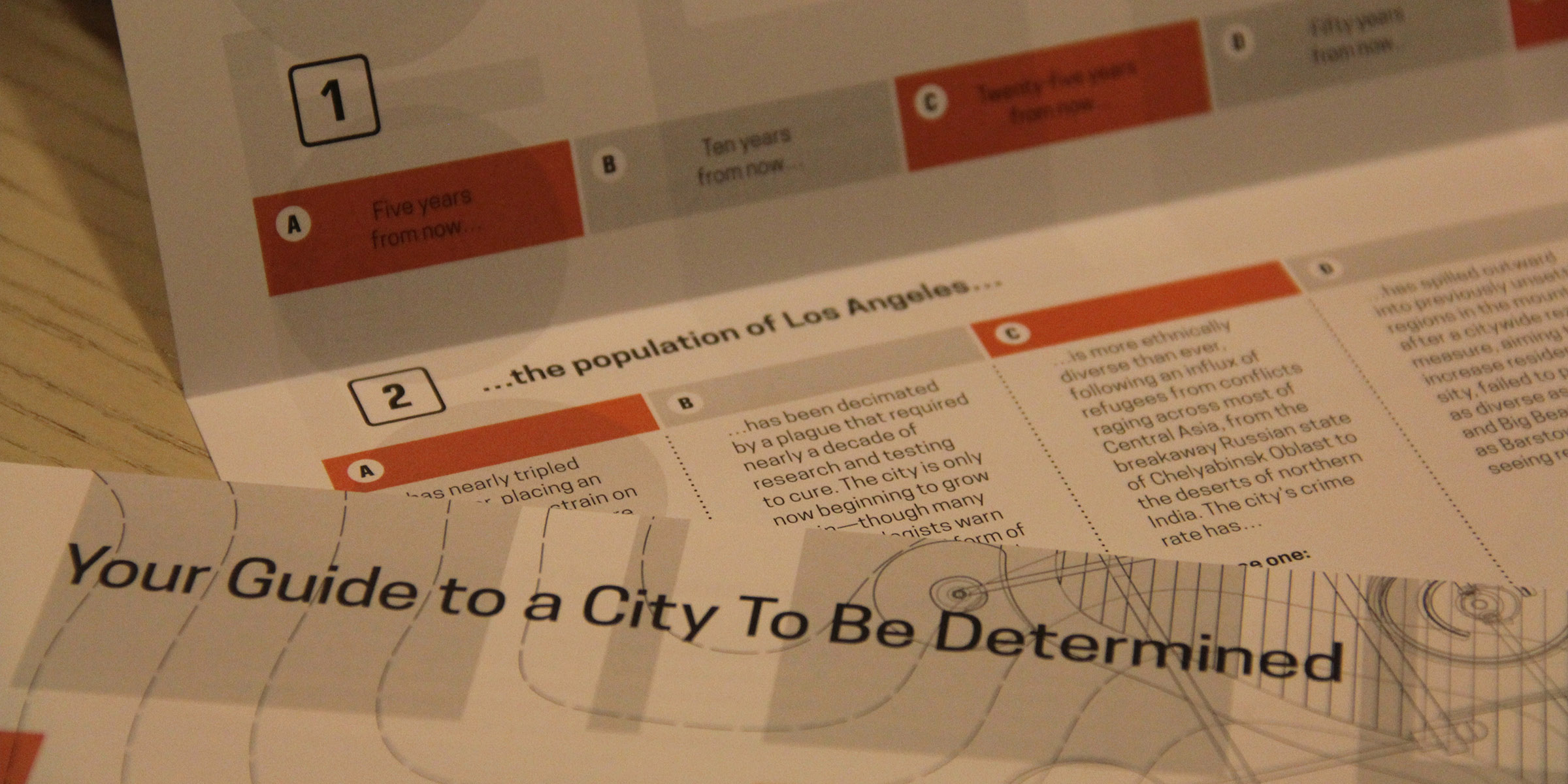

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

This is purely promotional, but I wanted to mention that I am up in San Francisco for two nights to speak as part of

This is purely promotional, but I wanted to mention that I am up in San Francisco for two nights to speak as part of

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Abandoned Packard plant in Detroit, via

[Image: Abandoned Packard plant in Detroit, via

[Image: From

[Image: From