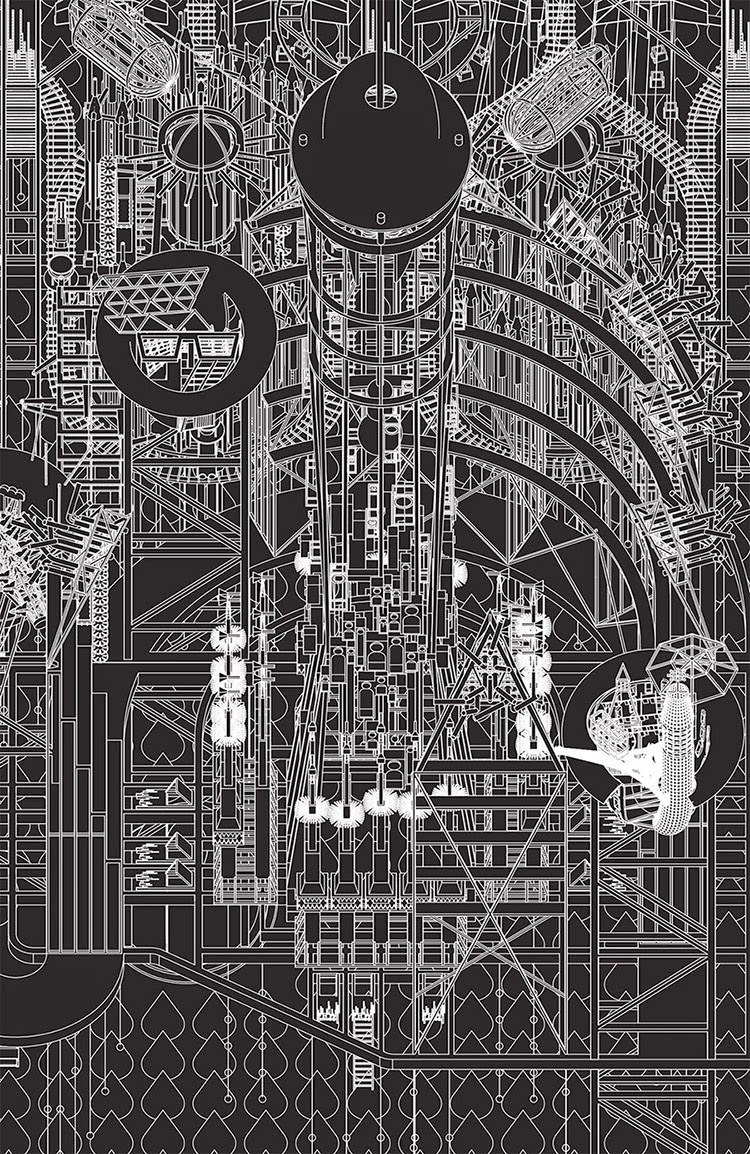

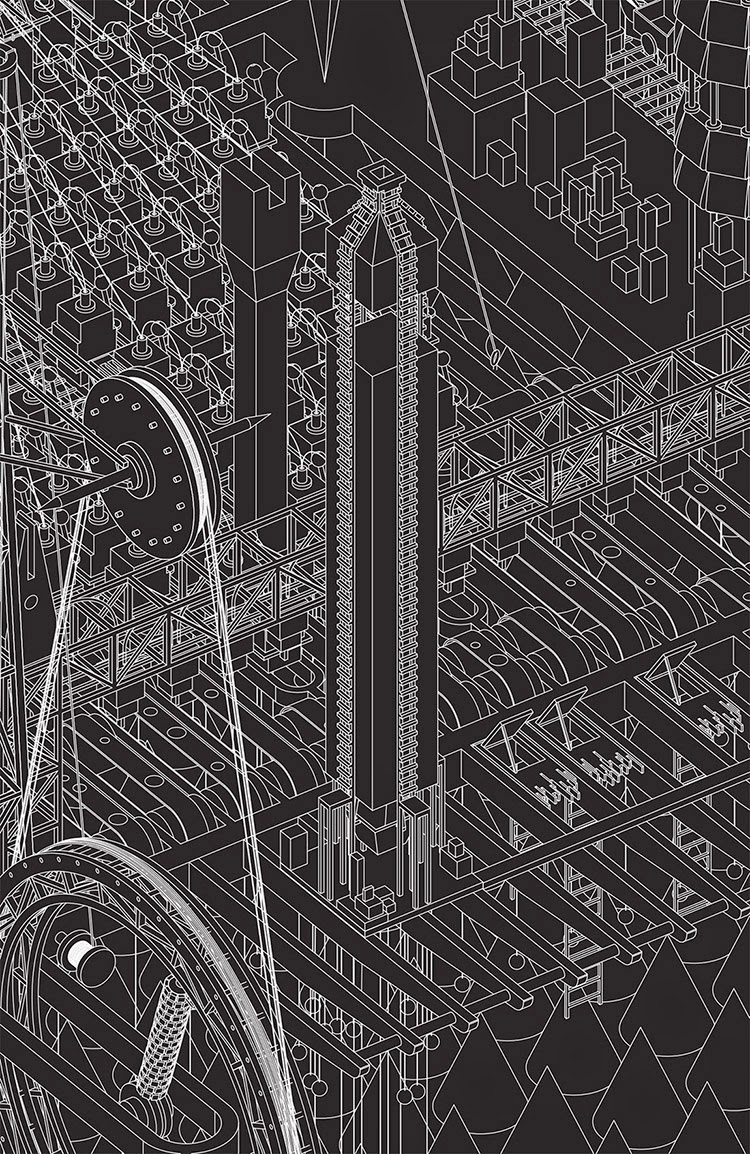

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

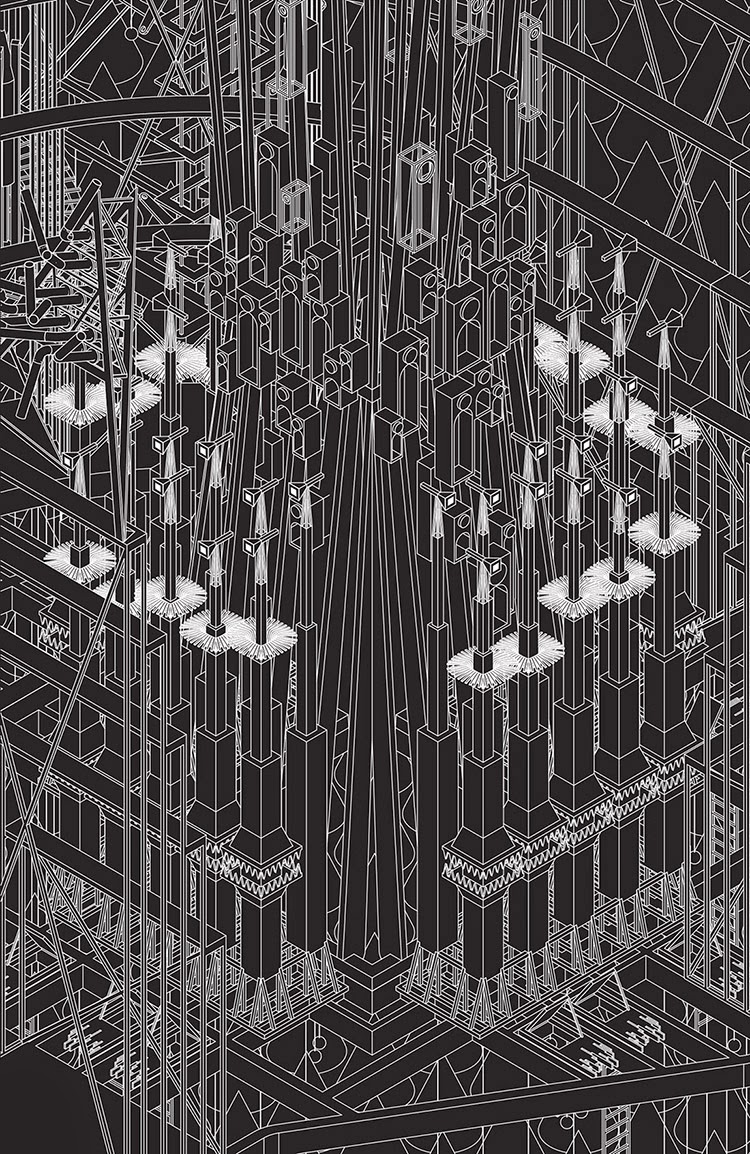

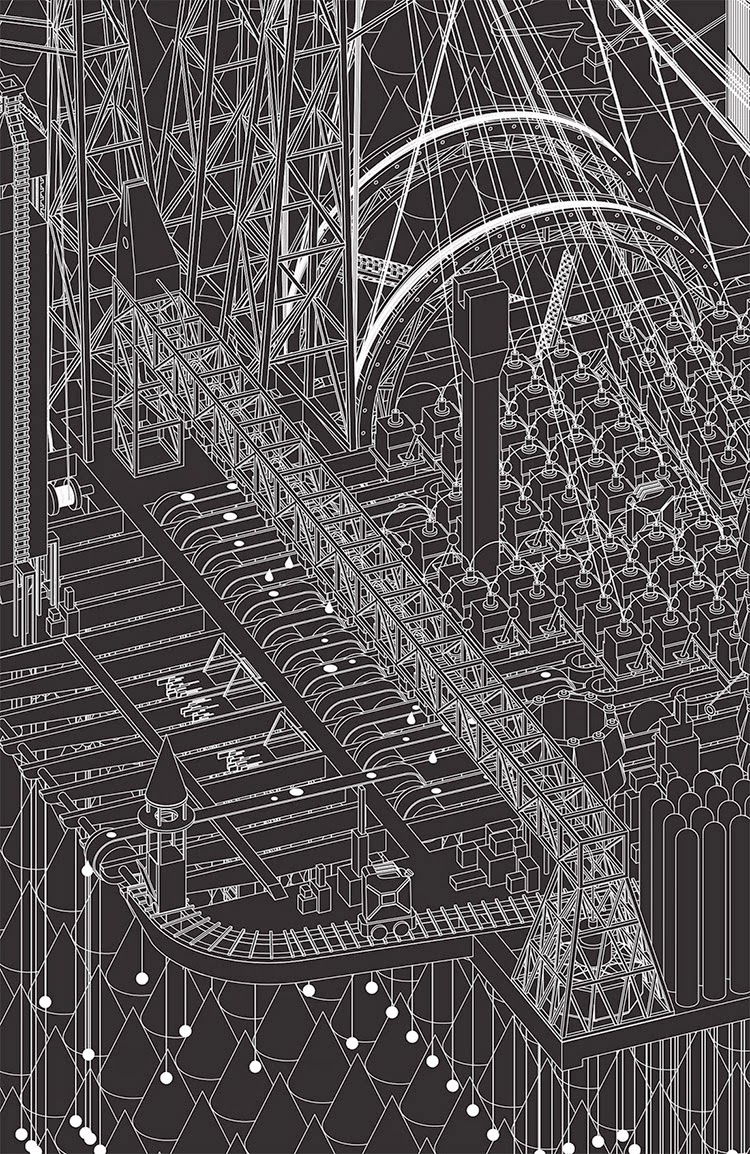

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

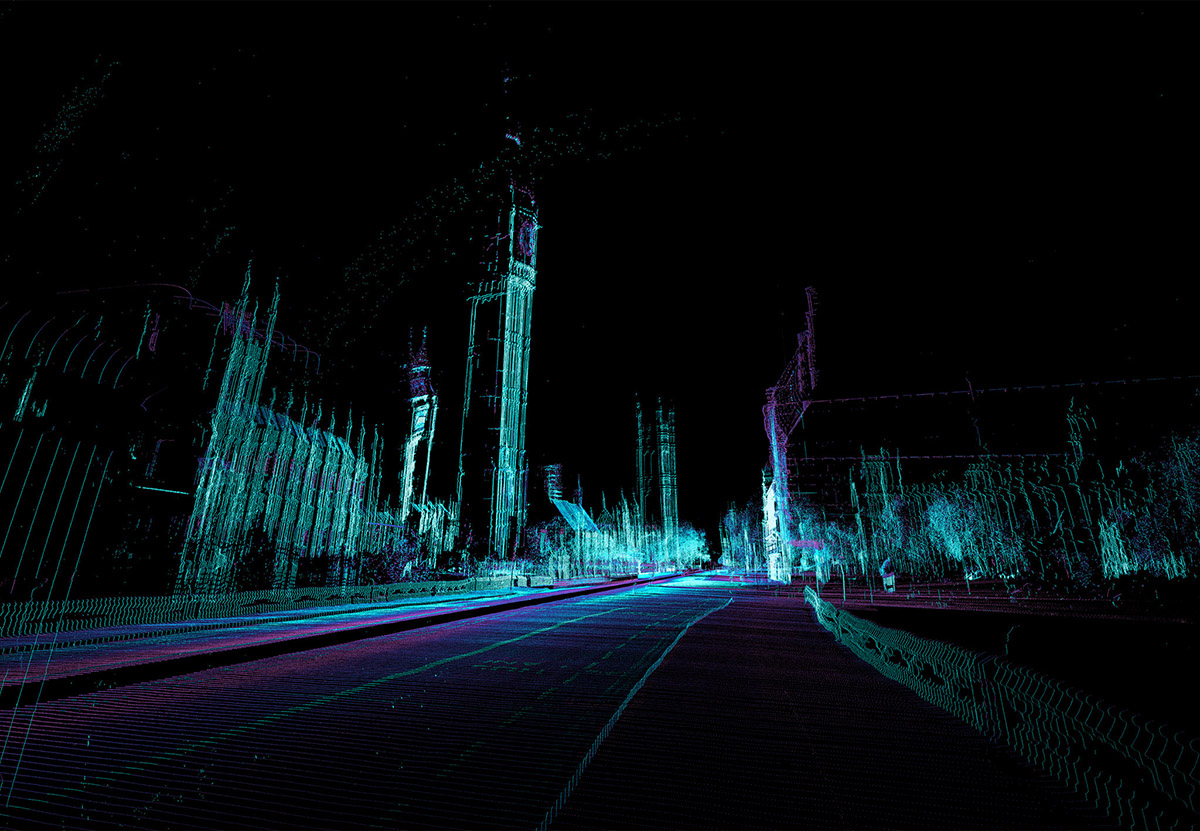

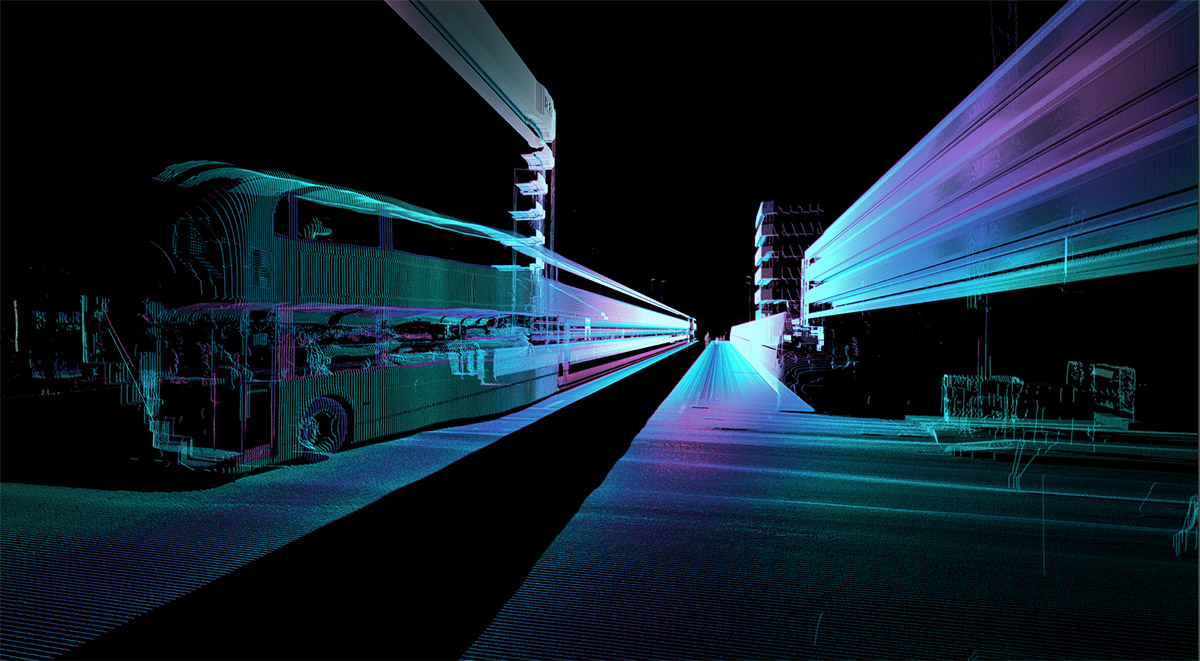

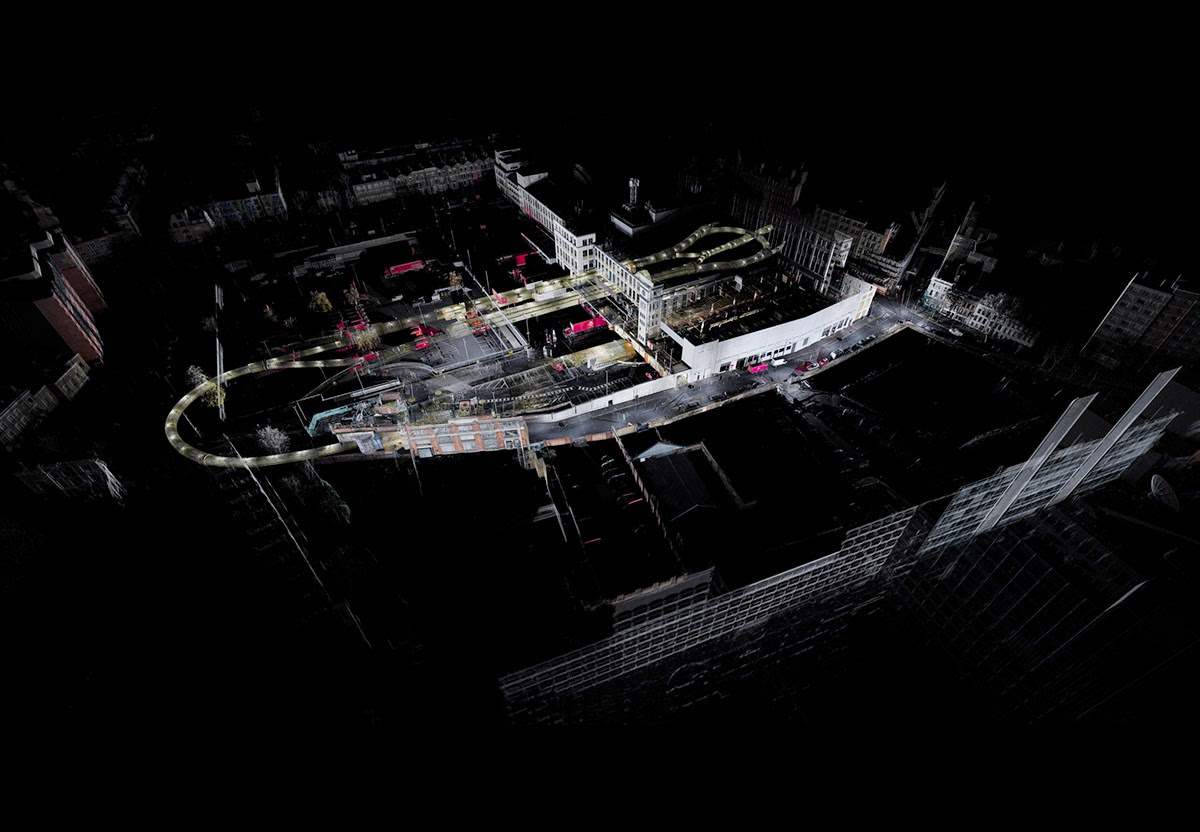

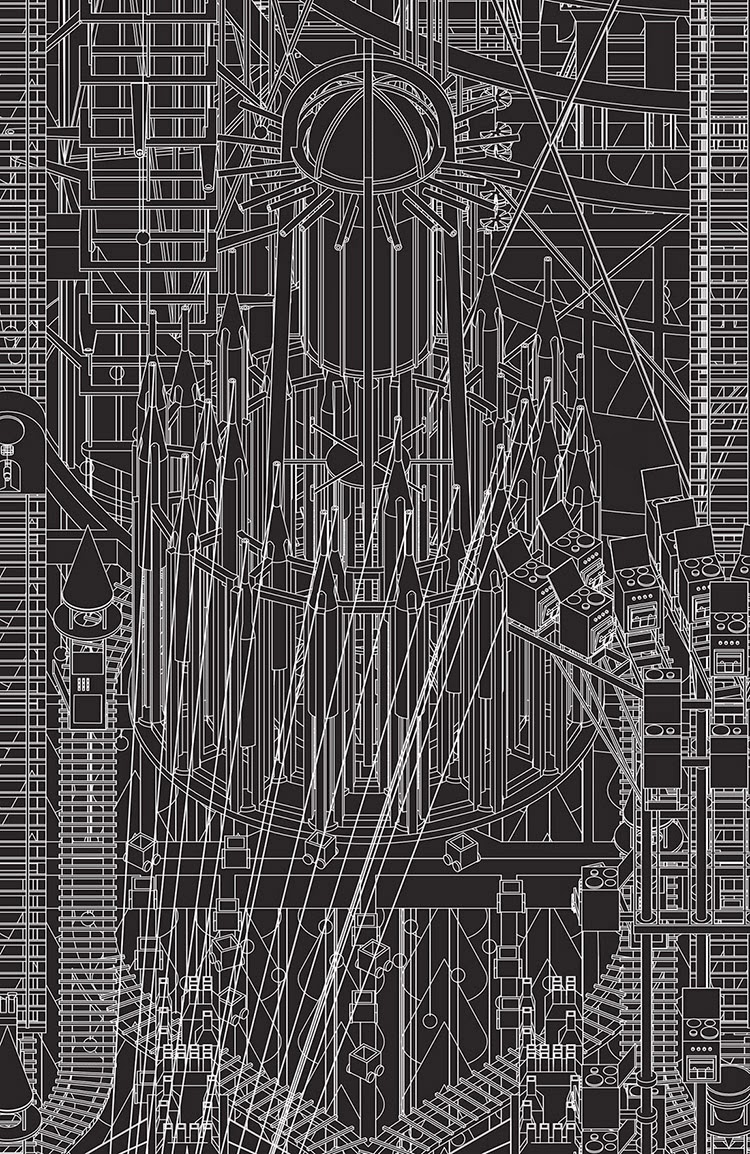

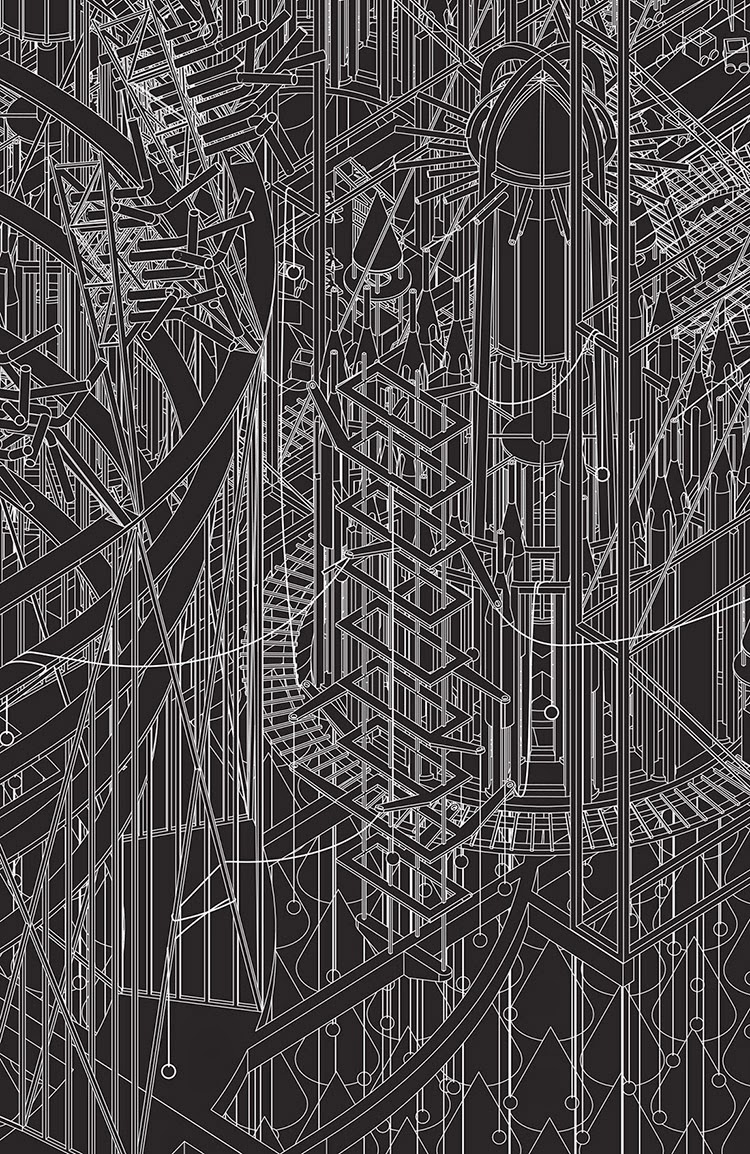

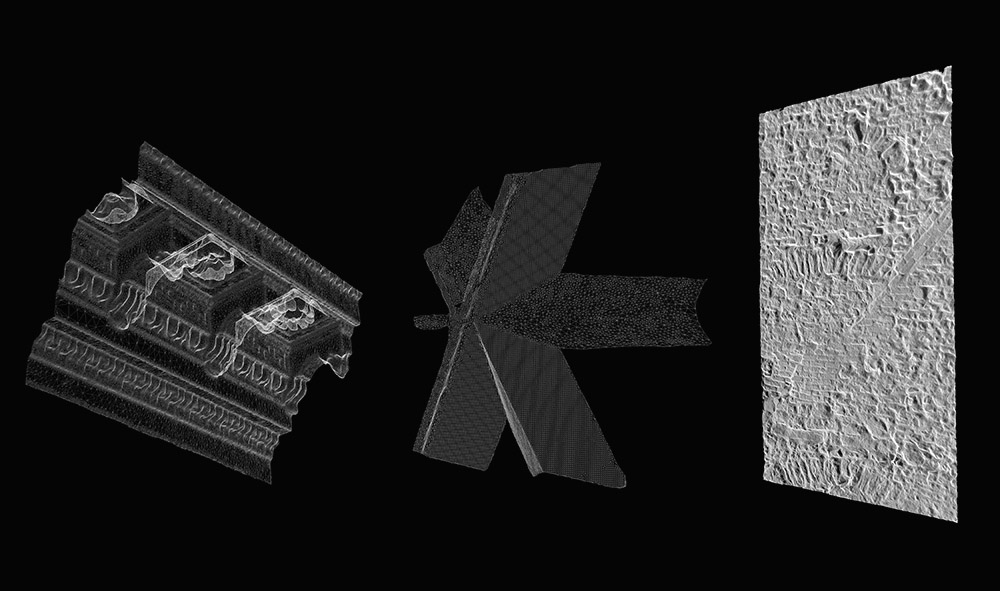

Understanding how driverless cars see the world also means understanding how they mis-see things: the duplications, glitches, and scanning errors that, precisely because of their deviation from human perception, suggest new ways of interacting with and experiencing the built environment.

Stepping into or through the scanners of autonomous vehicles in order to look back at the world from their perspective is the premise of a short feature I’ve written for this weekend’s edition of The New York Times Magazine.

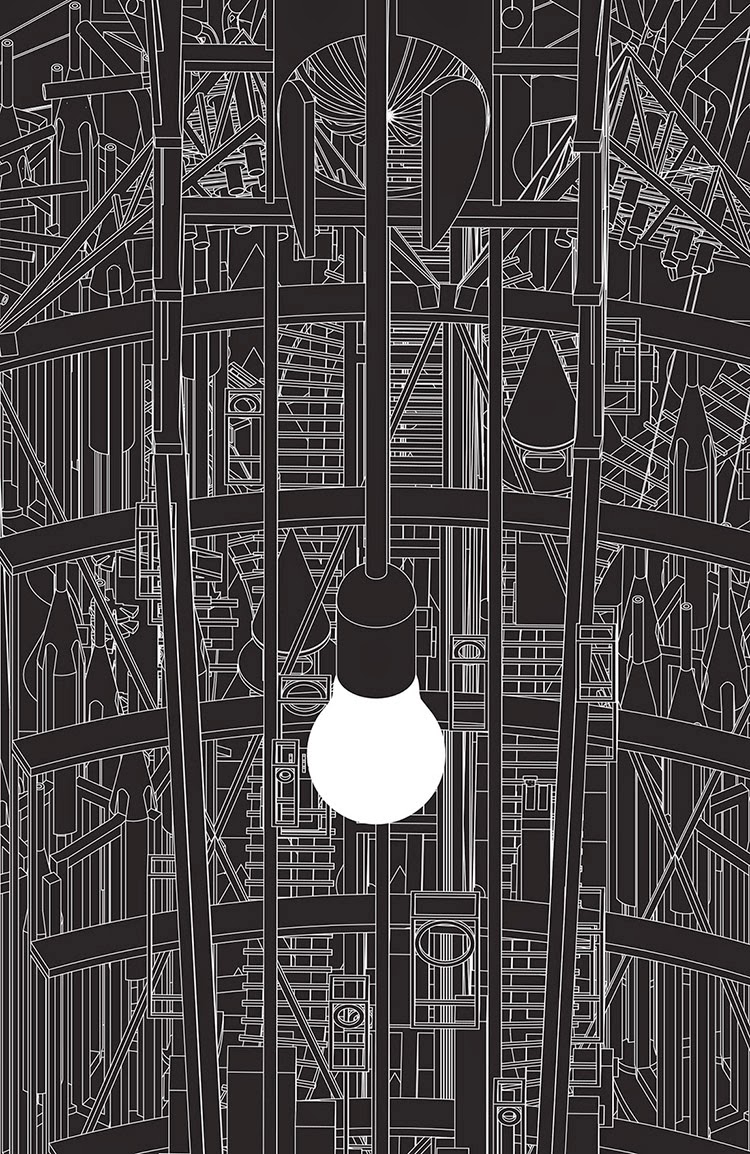

For a new series of urban images, Matt Shaw and Will Trossell of ScanLAB Projects tuned, tweaked, and augmented a LiDAR unit—one of the many tools used by self-driving vehicles to navigate—and turned it instead into something of an artistic device for experimentally representing urban space.

The resulting shots show the streets, bridges, and landmarks of London transformed through glitches into “a landscape of aging monuments and ornate buildings, but also one haunted by duplications and digital ghosts”:

The city’s double-decker buses, scanned over and over again, become time-stretched into featureless mega-structures blocking whole streets at a time. Other buildings seem to repeat and stutter, a riot of Houses of Parliament jostling shoulder to shoulder with themselves in the distance. Workers setting out for a lunchtime stroll become spectral silhouettes popping up as aberrations on the edge of the image. Glass towers unravel into the sky like smoke. Trossell calls these “mad machine hallucinations,” as if he and Shaw had woken up some sort of Frankenstein’s monster asleep inside the automotive industry’s most advanced imaging technology.

Along the way I had the pleasure of speaking to Illah Nourbakhsh, a professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon and the author of Robot Futures, a book I previously featured here on the blog back in 2013. Nourbakhsh is impressively adept at generating potential narrative scenarios—speculative accidents, we might call them—in which technology might fail or be compromised, and his take on the various perceptual risks or interpretive short-comings posed by autonomous vehicle technology was fascinating.

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

[Image by ScanLAB Projects for The New York Times Magazine].

Alas, only one example from our long conversation made it into the final article, but it is worth repeating. Nourbakhsh used “the metaphor of the perfect storm to describe an event so strange that no amount of programming or image-recognition technology can be expected to understand it”:

Imagine someone wearing a T-shirt with a STOP sign printed on it, he told me. “If they’re outside walking, and the sun is at just the right glare level, and there’s a mirrored truck stopped next to you, and the sun bounces off that truck and hits the guy so that you can’t see his face anymore—well, now your car just sees a stop sign. The chances of all that happening are diminishingly small—it’s very, very unlikely—but the problem is we will have millions of these cars. The very unlikely will happen all the time.”

The most interesting takeaway from this sort of scenario, however, is not that the technology is inherently flawed or limited, but that these momentary mirages and optical illusions are not, in fact, ephemeral: in a very straightforward, functional sense, they become a physical feature of the urban landscape because they exert spatial influences on the machines that (mis-)perceive them.

Nourbakhsh’s STOP sign might not “actually” be there—but it is actually there if it causes a self-driving car to stop.

Immaterial effects of machine vision become digitally material landmarks in the city, affecting traffic and influencing how machines safely operate. But, crucially, these are landmarks that remain invisible to human beings—and it is ScanLAB’s ultimate representational goal here to explore what it means to visualize them.

While, in the piece, I compare ScanLAB’s work to the heyday of European Romanticism—that ScanLAB are, in effect, documenting an encounter with sublime and inhuman landscapes that, here, are not remote mountain peaks but the engineered products of computation—writer Asher Kohn suggested on Twitter that, rather, it should be considered “Italian futurism made real,” with sweeping scenes of streets and buildings unraveling into space like digital smoke. It’s a great comparison, and worth developing at greater length.

For now, check out the full piece over at The New York Times Magazine: “The Dream Life of Driverless Cars.”

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by

[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by  [Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by

[Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by  [Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by

[Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by  [Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by

[Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by  [Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by

[Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by  [Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by

[Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by  [Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by

[Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by  [Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by

[Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by

[Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Images: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Images: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy  [Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

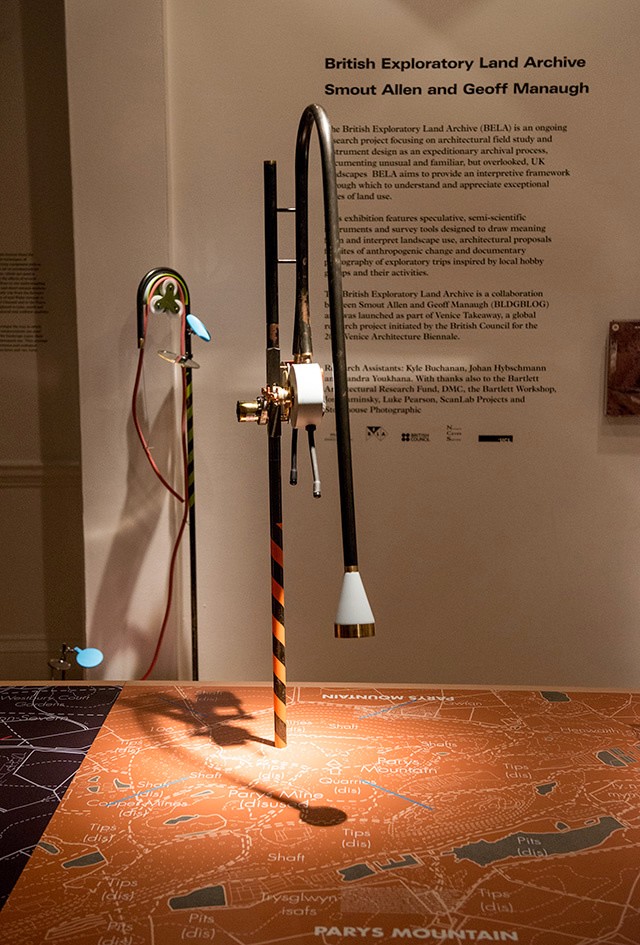

Last week, over at the

Last week, over at the  Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by

Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the  From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the

From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since  In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with

In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with  This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the

This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.  The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the

The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the  Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the

Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the

The exhibition is

The exhibition is

[Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “

[Images: From the “

[Images: From the “ [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Scans of a

[Image: Scans of a