Last week, over at the Architectural Association in London, a new exhibition opened, continuing the work of the British Exploratory Land Archive, an ongoing collaboration between myself and architects Mark Smout & Laura Allen of Smout Allen.

Last week, over at the Architectural Association in London, a new exhibition opened, continuing the work of the British Exploratory Land Archive, an ongoing collaboration between myself and architects Mark Smout & Laura Allen of Smout Allen.

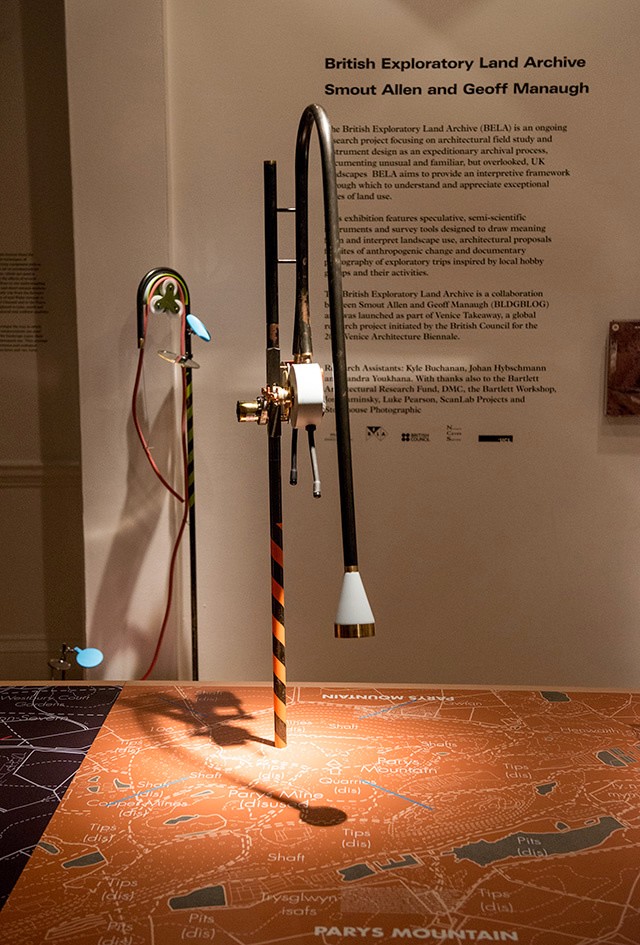

Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by Stonehouse Photographic. These show not only the models, but also the show’s enormous wall-sized photographs and various explanatory texts.

Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by Stonehouse Photographic. These show not only the models, but also the show’s enormous wall-sized photographs and various explanatory texts.

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the Nottingham Caves Survey, to an architectural model the size and shape of a pool table, its part precision 3D-printed for us by Williams, of Formula 1 race car fame. Williams—awesomely and generously—also collaborated with us in helping come up with a new, speculative use of their hybrid flywheel technology (more on this, below).

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the Nottingham Caves Survey, to an architectural model the size and shape of a pool table, its part precision 3D-printed for us by Williams, of Formula 1 race car fame. Williams—awesomely and generously—also collaborated with us in helping come up with a new, speculative use of their hybrid flywheel technology (more on this, below).

From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the Landscape Futures exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art to landscape-scale devices printing new islands out of redistributed silt—a kind of dredge-jet printer spraying archipelagos along the length of the Severn—the scale and range of the objects on display is pretty thrilling to see.

From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the Landscape Futures exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art to landscape-scale devices printing new islands out of redistributed silt—a kind of dredge-jet printer spraying archipelagos along the length of the Severn—the scale and range of the objects on display is pretty thrilling to see.

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since last summer’s Venice Biennale, I am fundamentally an outside observer on all of this, simply admiring Smout Allen’s incredible tenacity and technical handiwork whilst throwing out the occasional idea for new projects and proposals.

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since last summer’s Venice Biennale, I am fundamentally an outside observer on all of this, simply admiring Smout Allen’s incredible tenacity and technical handiwork whilst throwing out the occasional idea for new projects and proposals.

In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with Williams: one of the proposed projects in the exhibition is a “flywheel reservoir” for the Isle of Sheppey.

In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with Williams: one of the proposed projects in the exhibition is a “flywheel reservoir” for the Isle of Sheppey.

This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the London Array would be held in reserve.

This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the London Array would be held in reserve.

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own hybrid flywheel technology, normally used in Formula 1 race cars.

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own hybrid flywheel technology, normally used in Formula 1 race cars.

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.

The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the London Array, brought to you by the same technology that helps power race cars.

The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the London Array, brought to you by the same technology that helps power race cars.

Briefly, I was also interested to see that the little 3D-printed gears and pieces, when they first came out of the printer and had not yet been cleaned up or polished, looked remarkably—but inadvertently—like a project by the late Lebbeus Woods.

Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the Architectural Association for hosting the exhibition (in particular, Vanessa Norwood for so enthusiastically making it happen); to the small but highly motivated group of former students from the Bartlett School of Architecture, who helped to fabricate some of the exhibition’s other models and to organize some the British Exploratory Land Archive’s earlier projects; to the Nottingham Caves Survey for generously donating a trove of laser-scanning data for us to use in one of the models, and to ScanLAB Projects for helping convert that laser data into realizable 3D form; to UCL for the financial support and facilities; to Stonehouse Photographic, who not only was on hand to document the opening soirée but who also produced the massive photos you see leaning against the walls in the images reproduced here; and—why not?—to Sir Peter Cook, one of my own architectural heroes, for stopping by the exhibition on its opening night to say hello.

Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the Architectural Association for hosting the exhibition (in particular, Vanessa Norwood for so enthusiastically making it happen); to the small but highly motivated group of former students from the Bartlett School of Architecture, who helped to fabricate some of the exhibition’s other models and to organize some the British Exploratory Land Archive’s earlier projects; to the Nottingham Caves Survey for generously donating a trove of laser-scanning data for us to use in one of the models, and to ScanLAB Projects for helping convert that laser data into realizable 3D form; to UCL for the financial support and facilities; to Stonehouse Photographic, who not only was on hand to document the opening soirée but who also produced the massive photos you see leaning against the walls in the images reproduced here; and—why not?—to Sir Peter Cook, one of my own architectural heroes, for stopping by the exhibition on its opening night to say hello.

The exhibition is open until December 14 at the Architectural Association. Read more about the project here.

The exhibition is open until December 14 at the Architectural Association. Read more about the project here.

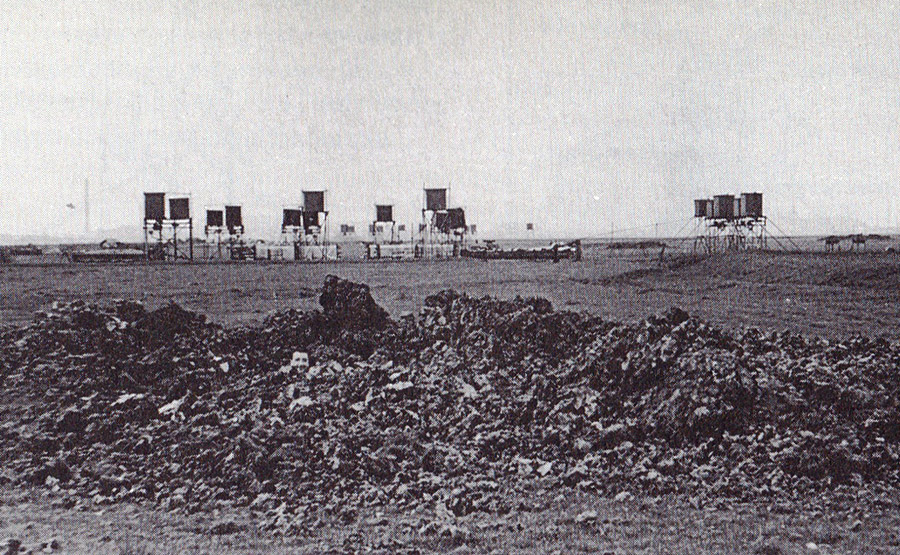

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of  [Image: A Starfish site burning, via the

[Image: A Starfish site burning, via the  [Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the

[Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the

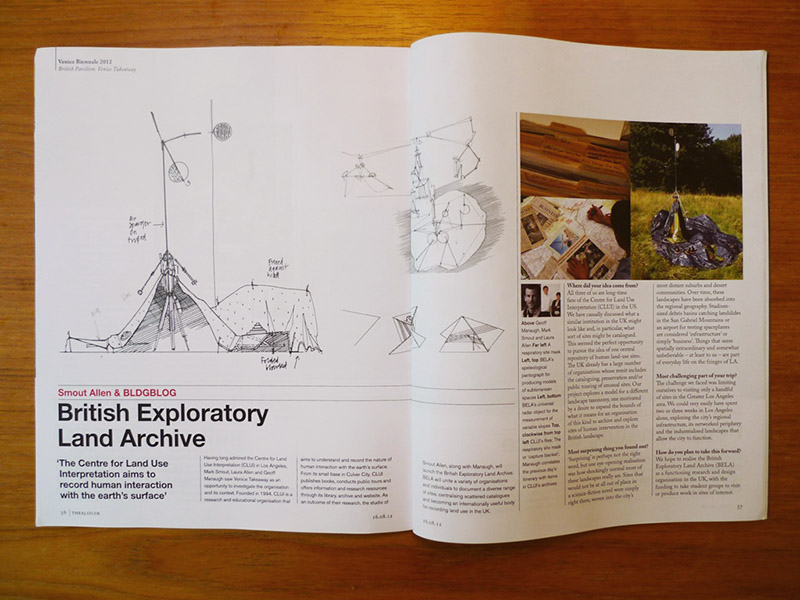

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

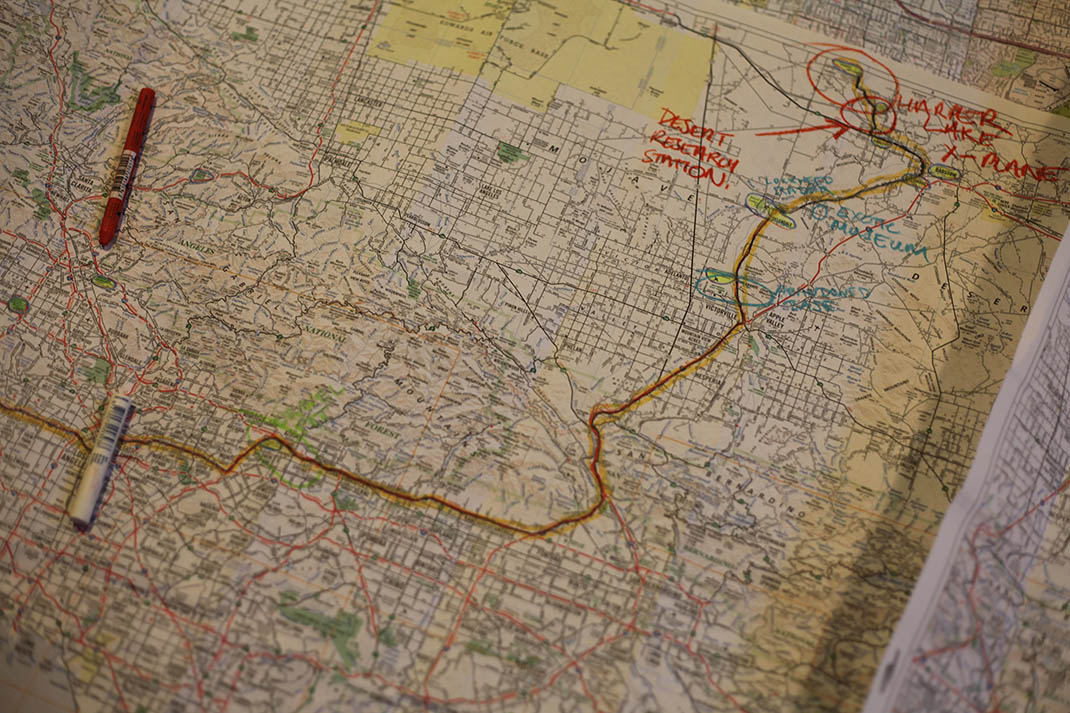

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

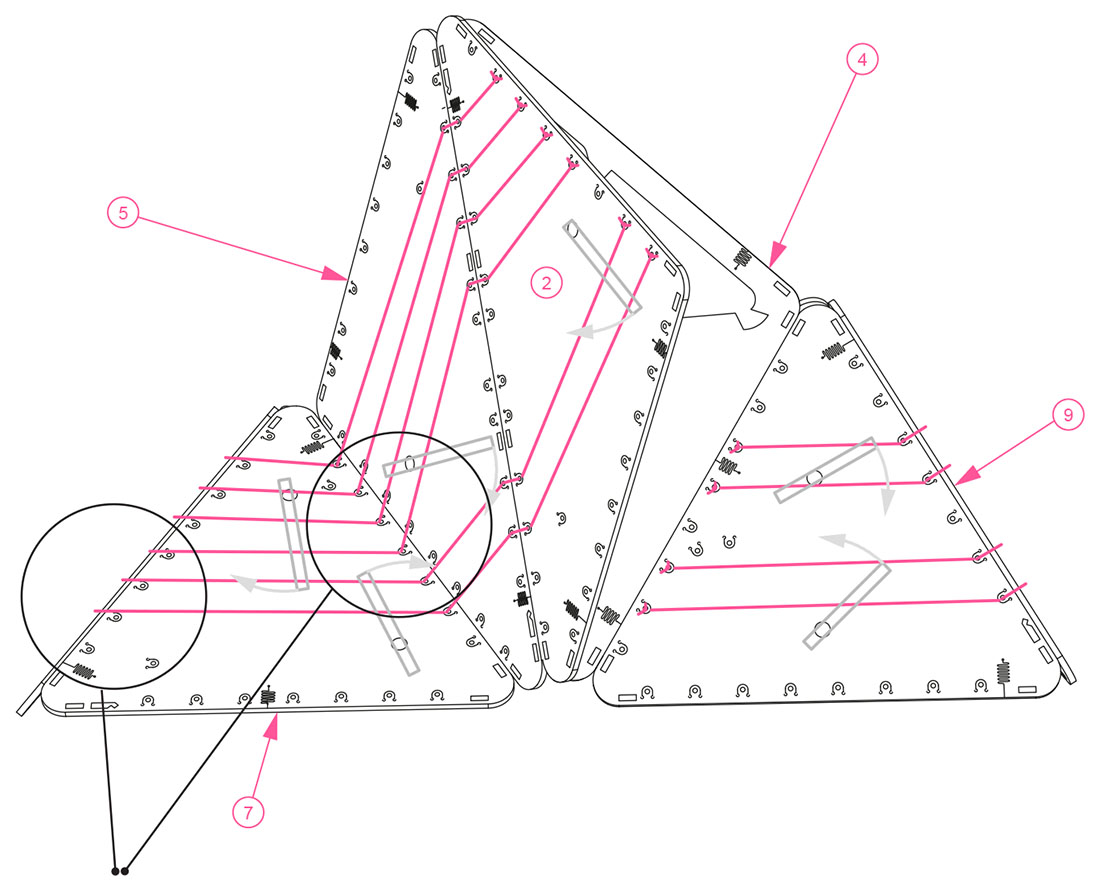

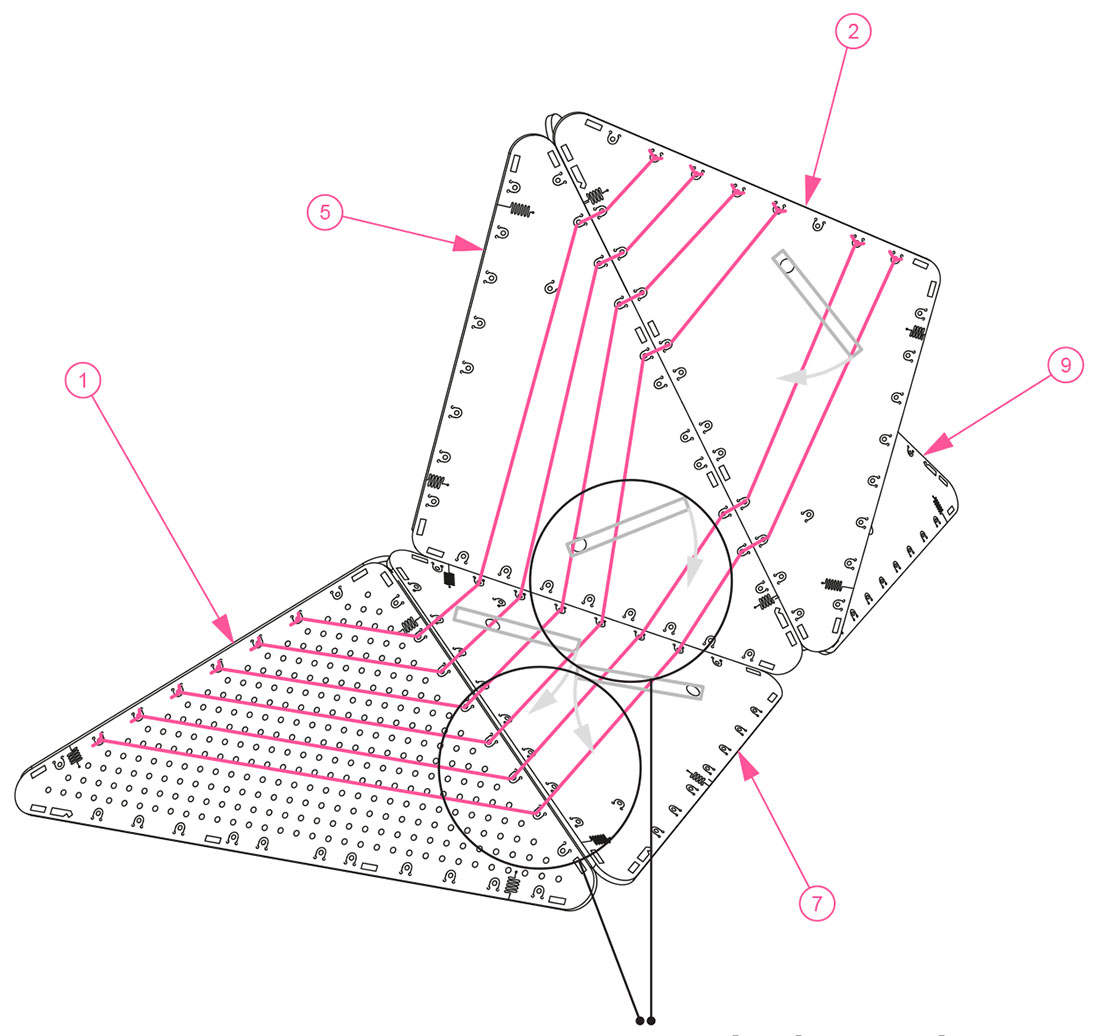

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].