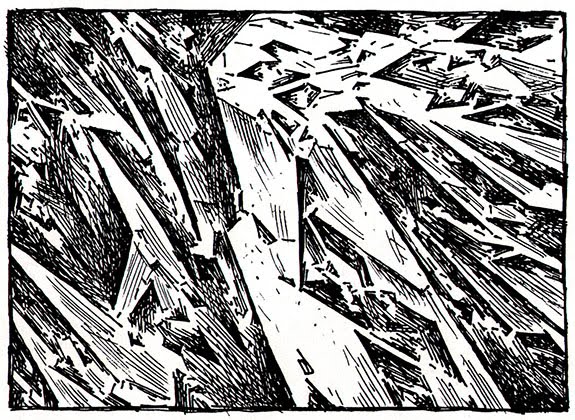

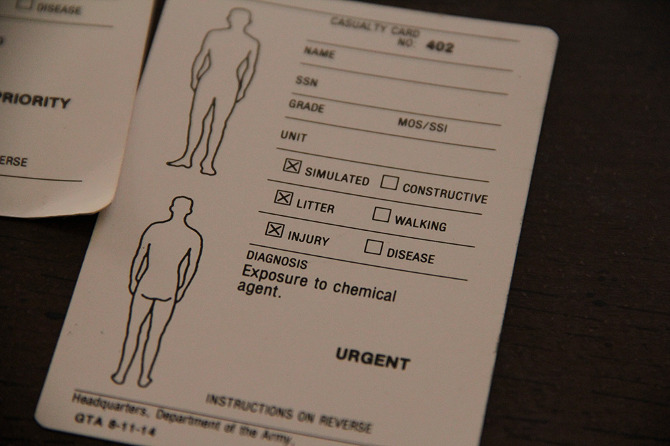

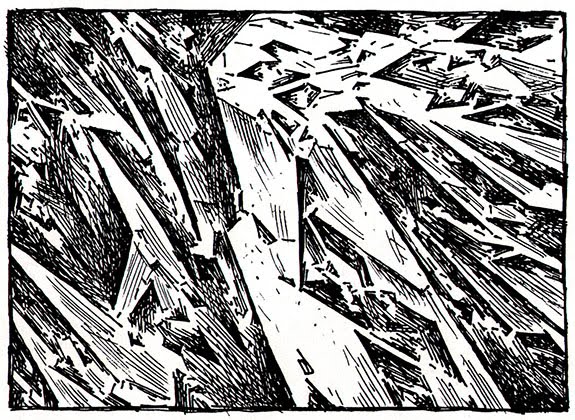

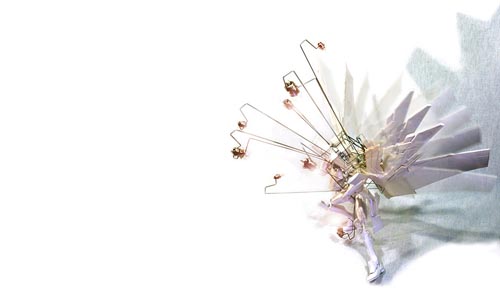

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)].

I thought I’d upload the course description for a studio I’ll be teaching this spring—starting next week, in fact—at Columbia University’s GSAPP on the architectural implications of seismic energy and the possibility of a San Andreas Fault National Park in California. The images in this post are just pages from the syllabus.

The overall idea is to look at architecture’s capacity for giving form to—or, in terms of the course description, its capacity to “make legible”—seismic energy as experienced along the San Andreas Fault. As the syllabus explains, we’ll achieve this, first, through the design and modeling of a series of architectural “devices”—not scientific instruments, but interpretive tools—that can interact with, spatially mediate, and/or augment the fault line, making the tectonic forces of the earth visible, audible, or otherwise sensible for a visiting public. From pendulums to prepared pianos, seismographs to shake tables, this invention and exploration of new mechanisms for the fault will fill the course’s opening three weeks.

The larger and more important impetus of the studio, however, is to look at the San Andreas Fault as a possible site for a future National Park, including all that this might entail, from questions of seismic risk and what it means to invite visitors into a place of terrestrial instability to the impossibility of preserving a landscape on the move. What might a San Andreas Fault National Park look like, we will ask, how could such a park best be managed, what architecture and infrastructure—from a visitors’ center to hiking way stations—would be appropriate for such a dynamic site, and, in the end, what does it mean to enshrine seismic movement as part of the historical narrative of the United States, suggesting that a fault line can be worthy of National Park status?

I’m also excited to say that we’ll be working in collaboration with Marc Weidenbaum’s Disquiet Junto, an online music collective who will be developing projects over the course of the spring that explore the sonic properties of the San Andreas Fault—a kind of soundtrack for the San Andreas. The results of these experiments will be uploaded to Soundcloud.

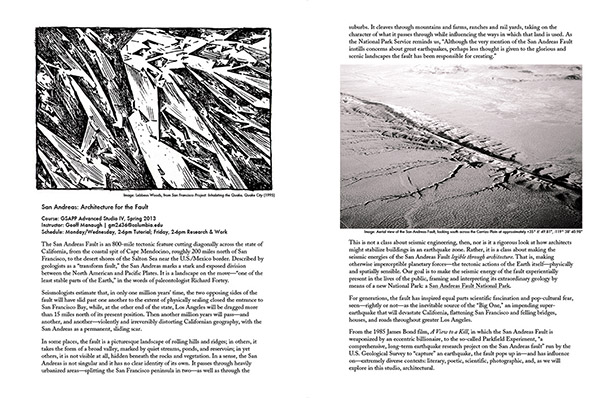

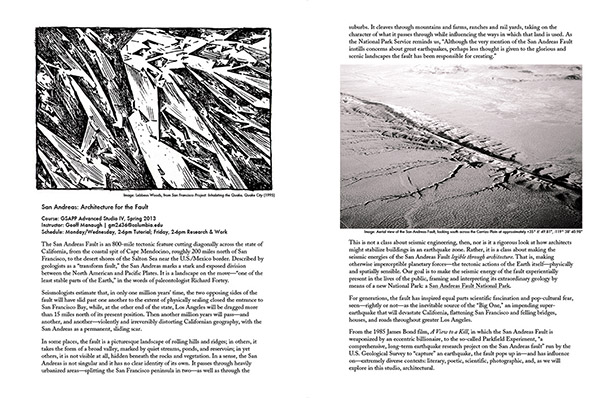

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995) and an aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, looking south across the Carrizo Plain at approximately +35° 6′ 49.81″, -119° 38′ 40.98″].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995) and an aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, looking south across the Carrizo Plain at approximately +35° 6′ 49.81″, -119° 38′ 40.98″].

Course: Columbia University GSAPP Advanced Studio IV, Spring 2013

Title: San Andreas: Architecture for the Fault

Instructor: Geoff Manaugh

The San Andreas Fault is a roughly 800-mile tectonic feature cutting diagonally across the state of California, from the coastal spit of Cape Mendocino, 200 miles north of San Francisco, to the desert shores of the Salton Sea near the U.S./Mexico border. Described by geologists as a “transform fault,” the San Andreas marks a stark and exposed division between the North American and Pacific Plates. It is a landscape on the move—“one of the least stable parts of the Earth,” in the words of paleontologist Richard Fortey, writing in his excellent book Earth: An Intimate History, and “one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes.”

Seismologists estimate that, in just one million years’ time, the two opposing sides of the fault will have slid past one another to the extent of physically sealing closed the entrance to San Francisco Bay; at the other end of the state, Los Angeles will have been dragged more than 15 miles north of its present position. But then another million years will pass—and another, and another—violently and unrecognizably distorting Californian geography, with the San Andreas as a permanent, sliding scar.

In some places today, the fault is a picturesque landscape of rolling hills and ridges; in others, it is a broad valley, marked by quiet streams, ponds, and reservoirs; in yet others, it is not visible at all, hidden beneath the rocks and vegetation. In a sense, the San Andreas is not singular and it has no clear identity of its own, taking on the character of what it passes through whilst influencing the ways in which that land is used. The fault cuts through heavily urbanized areas—splitting the San Francisco peninsula in two—as well as through the suburbs. It cleaves through mountains and farms, ranches and rail yards. As the National Park Service reminds us, “Although the very mention of the San Andreas Fault instills concerns about great earthquakes, perhaps less thought is given to the glorious and scenic landscapes the fault has been responsible for creating.”

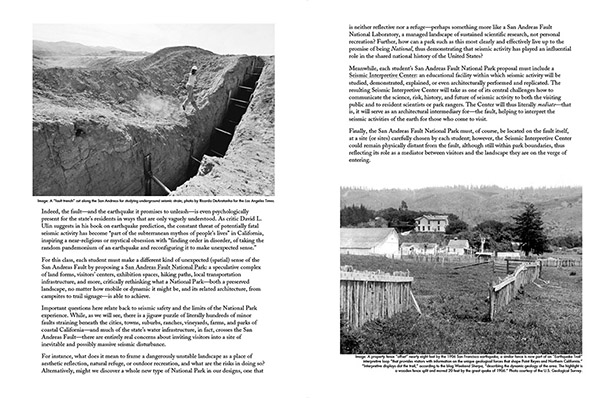

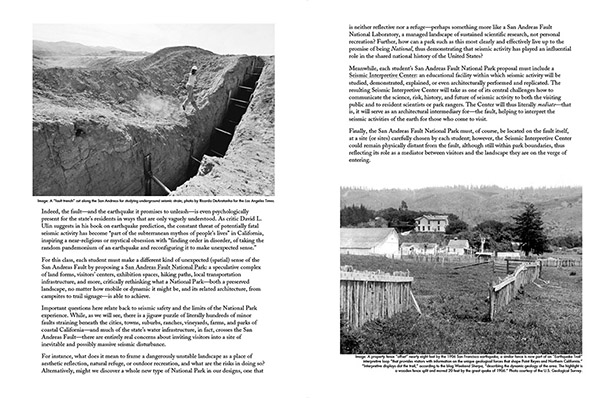

[Images: (left) A “fault trench” cut along the San Andreas for studying underground seismic strain; photo by Ricardo DeAratanha for the Los Angeles Times. (right) A property fence “offset” nearly eight feet by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; a similar fence is now part of an “Earthquake Trail” interpretive loop “that provides visitors with information on the unique geological forces that shape Point Reyes and Northern California.” “Interpretive displays dot the trail,” according to the blog Weekend Sherpa, “describing the dynamic geology of the area. The highlight is a wooden fence split and moved 20 feet by the great quake of 1906.” Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey].

[Images: (left) A “fault trench” cut along the San Andreas for studying underground seismic strain; photo by Ricardo DeAratanha for the Los Angeles Times. (right) A property fence “offset” nearly eight feet by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; a similar fence is now part of an “Earthquake Trail” interpretive loop “that provides visitors with information on the unique geological forces that shape Point Reyes and Northern California.” “Interpretive displays dot the trail,” according to the blog Weekend Sherpa, “describing the dynamic geology of the area. The highlight is a wooden fence split and moved 20 feet by the great quake of 1906.” Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey].

This is not a class about seismic engineering, however, nor is it a rigorous look at how architects might stabilize buildings in an earthquake zone. Rather, it is a class about making the seismic energies of the San Andreas Fault legible through architecture. That is, making otherwise imperceptible planetary forces—the tectonic actions of the Earth itself—physically and spatially sensible. Our goal is to make the seismic energy of the fault experientially present in the lives of the public, framing and interpreting its extraordinary geology by means of a new National Park: a San Andreas Fault National Park.

For generations, the fault has inspired equal parts scientific fascination and pop-cultural fear, seen—rightly or not—as the inevitable source of the “Big One,” an impending super-earthquake that will devastate California, flattening San Francisco and felling bridges, houses, and roads throughout greater Los Angeles.

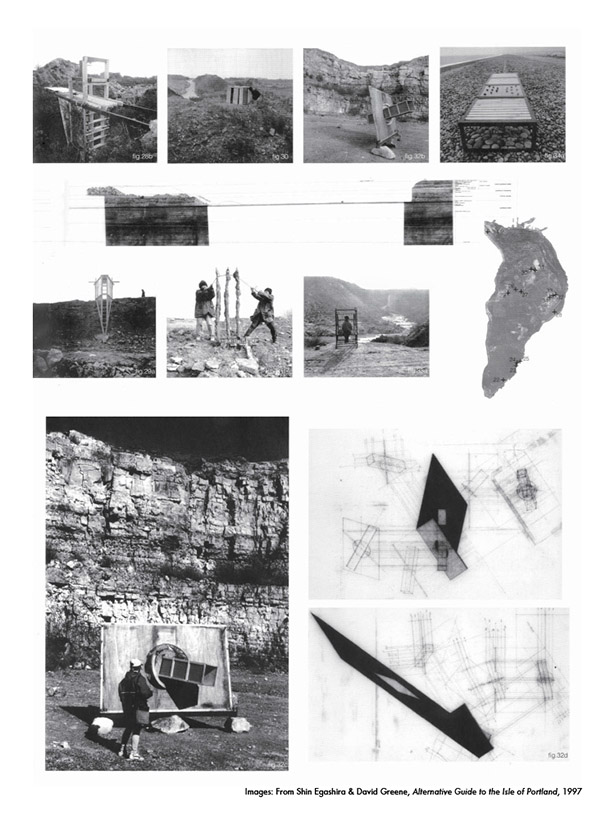

From the 1985 James Bond film, A View to a Kill, in which the San Andreas Fault is weaponized by an eccentric billionaire, to the so-called Parkfield Experiment, “a comprehensive, long-term earthquake research project on the San Andreas fault” run by the U.S. Geological Survey to “capture” an earthquake, the fault pops up in—and has influence on—extremely diverse contexts: literary, poetic, scientific, photographic, and, as we will explore in this studio, architectural.

Indeed, the fault—and the earthquake it promises to unleash—is even psychologically present for the state’s residents in ways that are only vaguely understood. As critic David L. Ulin suggests in his book The Myth of Solid Ground, on the promises and impossibilities of earthquake prediction, the constant threat of potentially fatal seismic activity has become “part of the subterranean mythos of people’s lives” in California, inspiring a near-religious or mystical obsession with “finding order in disorder, of taking the random pandemonium of an earthquake and reconfiguring it to make unexpected sense.”

For this class, each student must make a different kind of unexpected (spatial) sense of the San Andreas Fault by proposing a San Andreas Fault National Park: a speculative complex of land forms, visitors’ centers, exhibition spaces, hiking paths, local transportation infrastructure, and more, critically rethinking what a National Park—both a preserved landscape, no matter how mobile or dynamic it might be, and its related architecture, from campsites to trail signage—is able to achieve.

Important questions here relate back to seismic safety and the limits of the National Park experience. While, as we will see, there is a jigsaw puzzle of literally hundreds of minor faults straining beneath the cities, towns, suburbs, ranches, vineyards, farms, and parks of coastal California—and much of the state’s water infrastructure, in fact, crosses the San Andreas Fault—there are entirely real concerns about inviting visitors into a site of inevitable and possibly massive seismic disturbance.

For instance, what does it mean to frame a dangerously unstable landscape as a place of aesthetic reflection, natural refuge, or outdoor recreation, and what are the risks in doing so? Alternatively, might we discover a whole new type of National Park in our designs, one that is neither reflective nor a refuge—perhaps something more like a San Andreas Fault National Laboratory, a managed landscape of sustained scientific research, not personal recreation? Further, how can a park such as this most clearly and effectively live up to the promise of being National, thus demonstrating that seismic activity has played an influential role in the shared national history of the United States?

Meanwhile, each student’s San Andreas Fault National Park proposal must include a Seismic Interpretive Center: an educational facility within which seismic activity will be studied, demonstrated, explained, or even architecturally performed and replicated. The resulting Seismic Interpretive Center will take as one of its central challenges how to communicate the science, risk, history, and future of seismic activity to both the visiting public and to resident scientists or park rangers.

Finally, the San Andreas Fault National Park must, of course, be located on the fault itself, at a site (or sites) carefully chosen by each student; however, the Seismic Interpretive Center could remain physically distant from the fault, although still within park boundaries, thus reflecting its role as a mediator between visitors and the landscape they are on the verge of entering.

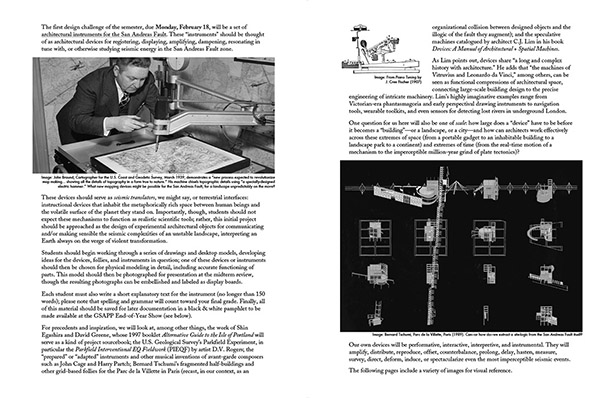

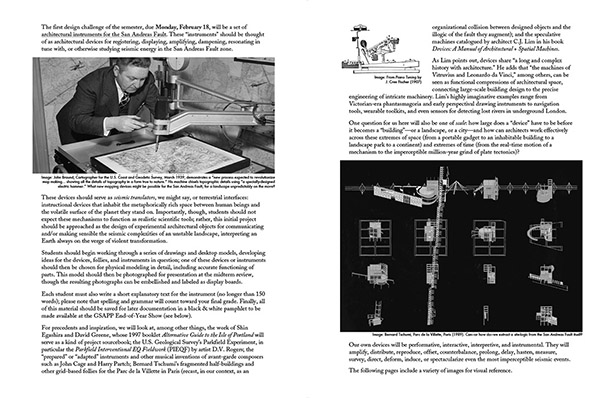

[Images: (left) John Braund, Cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, March 1939, demonstrates a “new process expected to revolutionize map making… showing all the details of topography in a form true to nature.” His machine chisels topographic details using “a specially-designed electric hammer.” What new mapping devices might be possible for the San Andreas Fault, for a landscape unpredictably on the move? (right top) From Piano Tuning by J. Cree Fischer (1907). (right bottom) Bernard Tschumi, Parc de la Villette, Paris (1989). Can—or how do—we extract a site-logic from the San Andreas Fault itself?].

[Images: (left) John Braund, Cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, March 1939, demonstrates a “new process expected to revolutionize map making… showing all the details of topography in a form true to nature.” His machine chisels topographic details using “a specially-designed electric hammer.” What new mapping devices might be possible for the San Andreas Fault, for a landscape unpredictably on the move? (right top) From Piano Tuning by J. Cree Fischer (1907). (right bottom) Bernard Tschumi, Parc de la Villette, Paris (1989). Can—or how do—we extract a site-logic from the San Andreas Fault itself?].

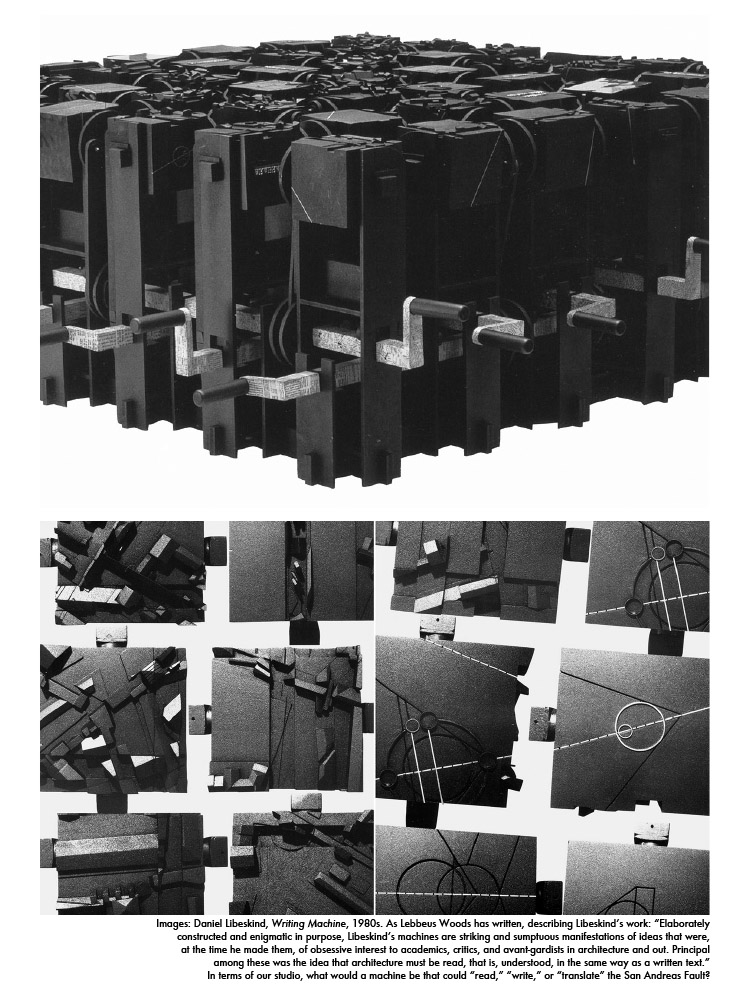

The first design challenge of the semester, due Monday, February 18, will be a set of architectural instruments for the San Andreas Fault. These “instruments” should be thought of as architectural devices for registering, displaying, amplifying, dampening, resonating in tune with, or otherwise studying seismic energy in the San Andreas Fault zone.

These devices should serve as seismic translators, we might say, or terrestrial interfaces: instructional devices that inhabit the metaphorically rich space between human beings and the volatile surface of the planet they stand on. Importantly, though, students should not expect these mechanisms to function as realistic scientific tools; rather, this initial project should be approached as the design of experimental architectural objects for communicating and/or making sensible the seismic complexities of an unstable landscape, interpreting an Earth always on the verge of violent transformation.

Students should begin working through a series of drawings and desktop models, developing ideas for the devices, follies, and instruments in question; one of these devices or instruments should then be chosen for physical modeling in detail, including accurate functioning of parts. This model should then be photographed for presentation at the midterm review, though the resulting photographs can be embellished and labeled as display boards. Each student must also write a short explanatory text for the instrument (no longer than 150 words).

Finally, all of this material should be saved for later documentation in a black & white pamphlet to be made available at the GSAPP End-of-Year Show.

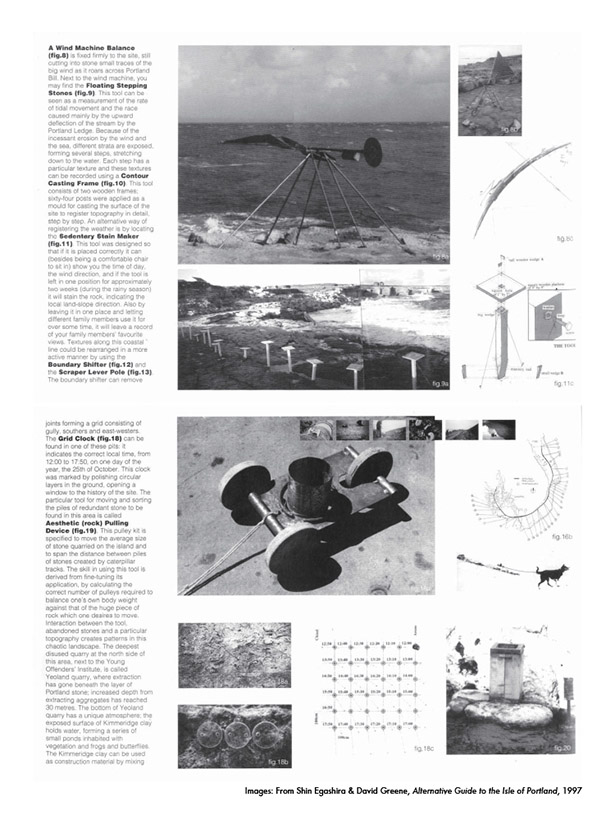

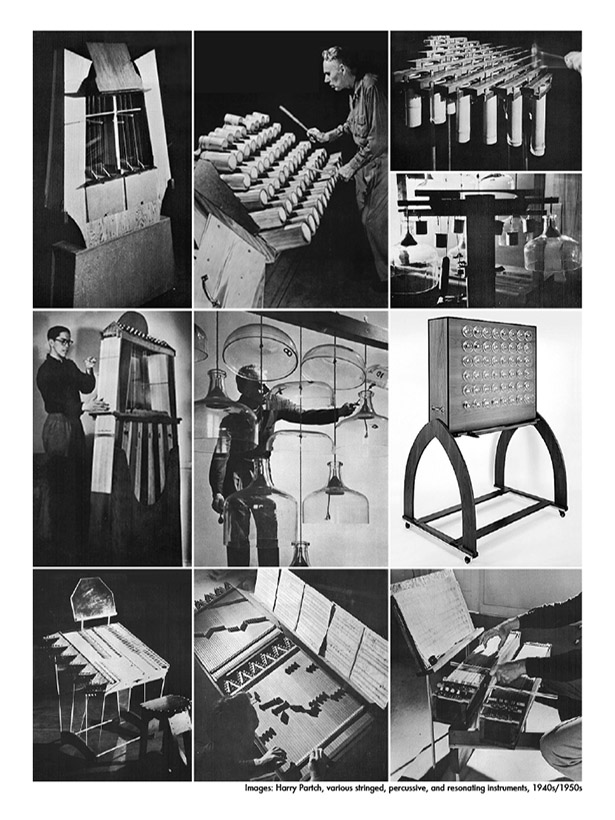

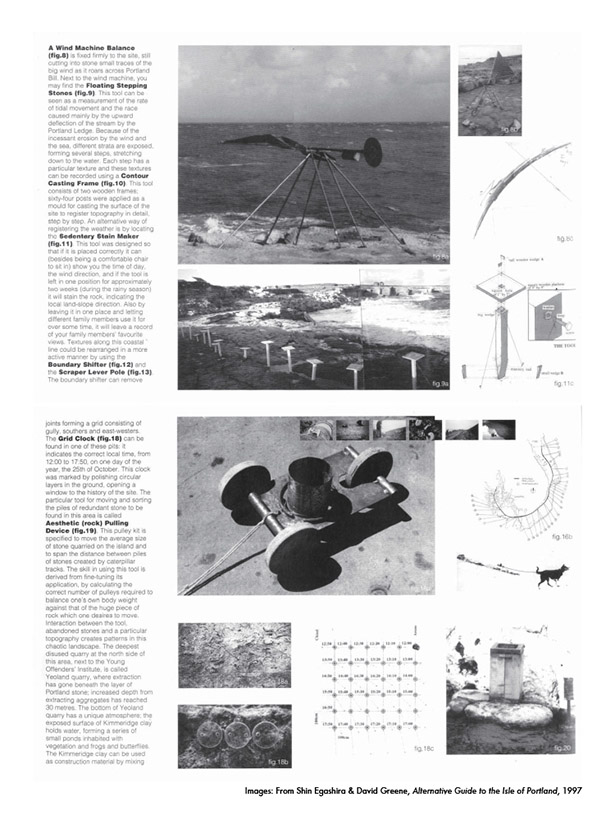

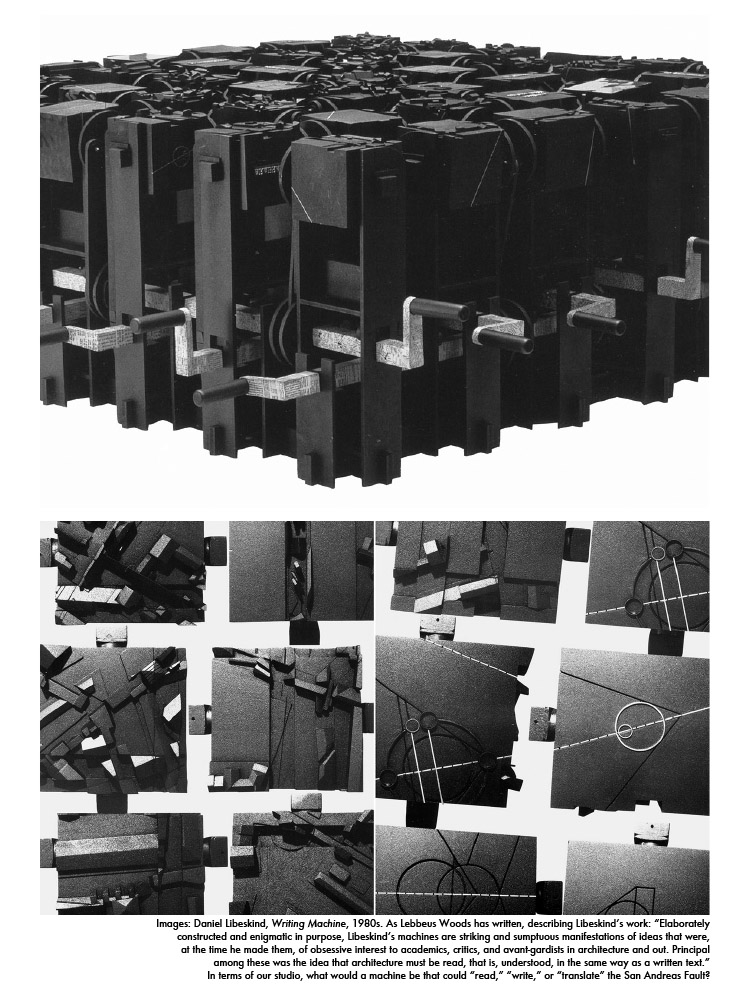

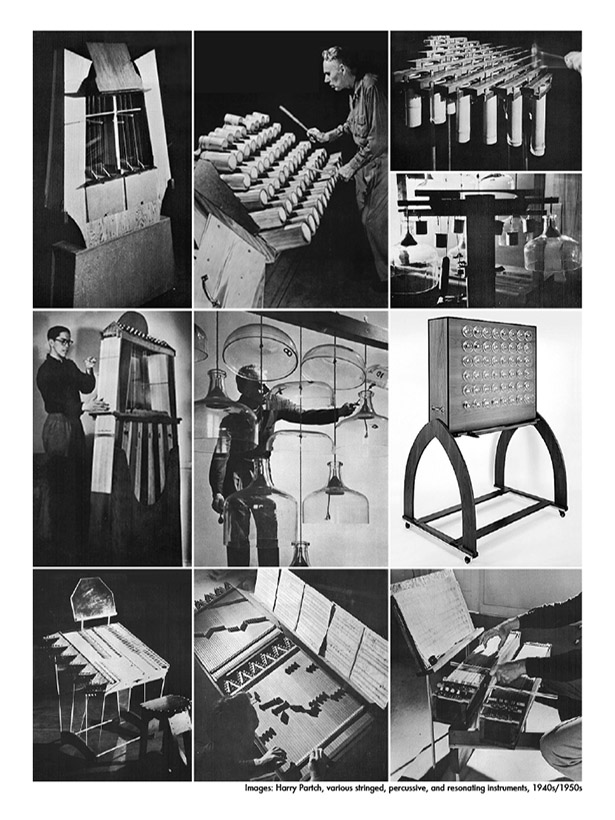

For precedents and inspiration, we will look at, among other things, the work of Shin Egashira and David Greene, whose 1997 booklet Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland will serve as a kind of project sourcebook; the U.S. Geological Survey’s Parkfield Experiment, in particular the Parkfield Interventional EQ Fieldwork (PIEQF) by artist D.V. Rogers; the “prepared” or “adapted” instruments and other musical inventions of avant-garde composers such as John Cage and Harry Partch; Bernard Tschumi’s fragmented half-buildings and other grid-based follies for the Parc de la Villette in Paris (recast, in our context, as an organizational collision between designed objects and the illogic of the fault they augment); and the speculative machines catalogued by architect C.J. Lim in his book Devices: A Manual of Architectural + Spatial Machines.

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

As Lim points out, devices share “a long and complex history with architecture.” He adds that “the machines of Vitruvius and Leonardo da Vinci,” among others, can be seen as functional compressions of architectural space, connecting large-scale building design to the precise engineering of intricate machinery. Lim’s highly imaginative examples range from Victorian-era phantasmagoria and early perspectival drawing instruments to navigation tools, wearable toolkits, and even sensors for detecting lost rivers in underground London.

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

One question for us here will also be in reference to scale: how large does a “device” have to be before it becomes a “building”—or a landscape, or a city—and how can architects work effectively across these extremes of space (from a portable gadget to an inhabitable building to a landscape park to a continent) and extremes of time (from the real-time motion of a mechanism to the imperceptible million-year grind of plate tectonics)?

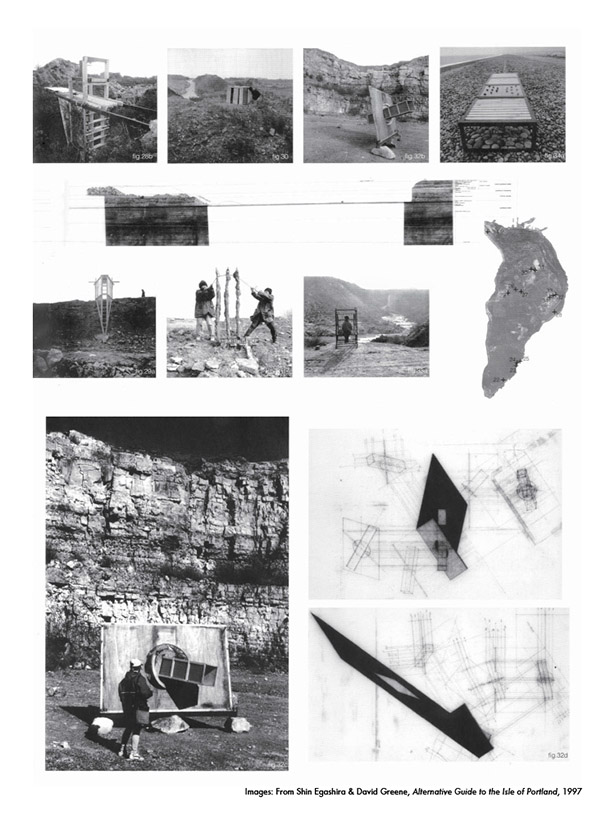

[Images: D.V. Rogers, Parkfield Interventional EQ Fieldwork (PIEQF), 2008. According to Rogers, PIEQF was “a geologically interactive, seismic machine earthwork temporarily installed in the remote township of Parkfield, Central California, USA. During ninety-one days of intervention, between the 18th [of] August and 16th [of] November 2008, the installation reflected 4000-4500 Californian seismic events. PIEQF interfaced with the US Geological Survey seismic monitoring network and was triggered by near real-time reported earthquake waves from magnitude (M) 0.1 and above… Surrounding the earthquake shake table and buried within the excavation at north, south, east, and west co-ordinate points, an array of vertical motion sensors were installed. These sensors (Geophones) were excited when walked over or jumped upon, causing the shake table to become mechanically active. Visitors to PIEQF engaged interactively with the installation becoming seismic events themselves when interacting with these sensors.”].

[Images: D.V. Rogers, Parkfield Interventional EQ Fieldwork (PIEQF), 2008. According to Rogers, PIEQF was “a geologically interactive, seismic machine earthwork temporarily installed in the remote township of Parkfield, Central California, USA. During ninety-one days of intervention, between the 18th [of] August and 16th [of] November 2008, the installation reflected 4000-4500 Californian seismic events. PIEQF interfaced with the US Geological Survey seismic monitoring network and was triggered by near real-time reported earthquake waves from magnitude (M) 0.1 and above… Surrounding the earthquake shake table and buried within the excavation at north, south, east, and west co-ordinate points, an array of vertical motion sensors were installed. These sensors (Geophones) were excited when walked over or jumped upon, causing the shake table to become mechanically active. Visitors to PIEQF engaged interactively with the installation becoming seismic events themselves when interacting with these sensors.”].

Our own devices will be performative, interactive, interpretive, and instrumental. They will amplify, distribute, reproduce, offset, counterbalance, prolong, delay, hasten, measure, survey, direct, deform, induce, or spectacularize even the most imperceptible seismic events.

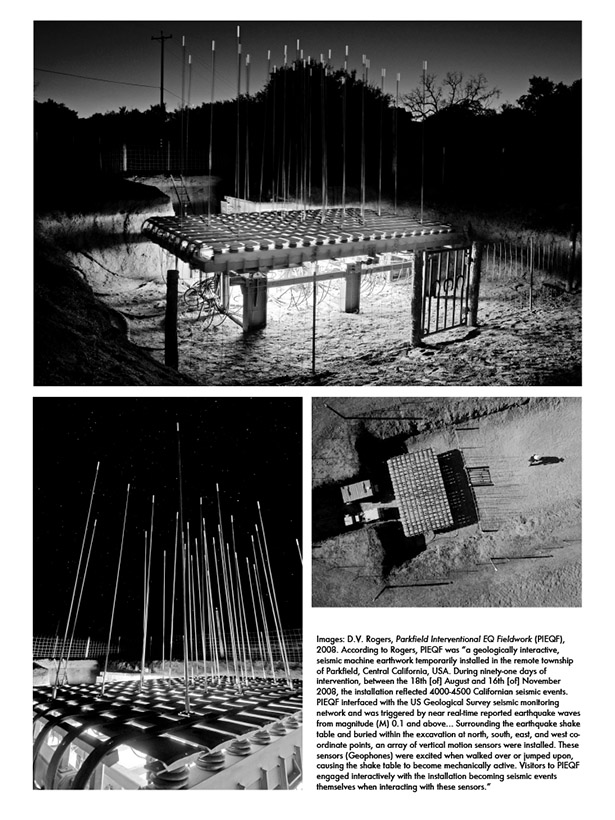

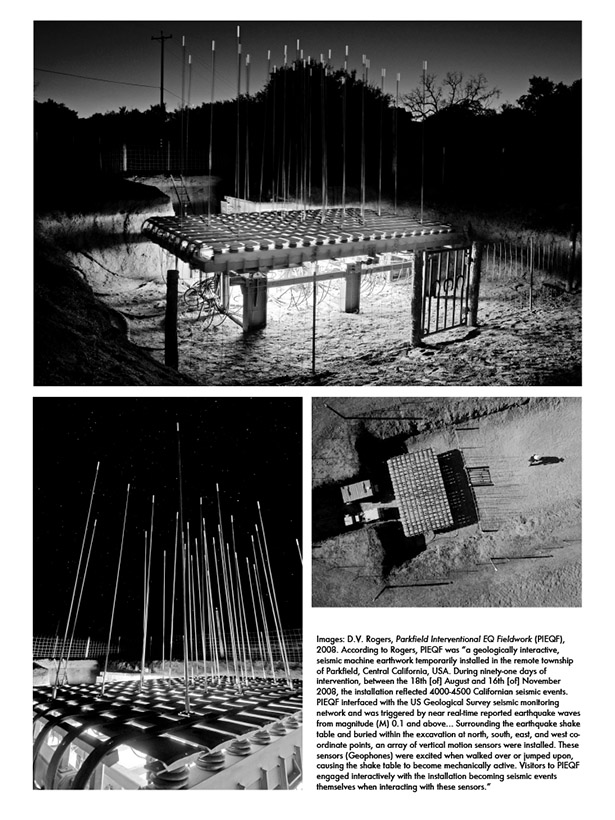

[Images: Daniel Libeskind, Writing Machine (1980s). As Lebbeus Woods has written, describing Libeskind’s work: “Elaborately constructed and enigmatic in purpose, Libeskind’s machines are striking and sumptuous manifestations of ideas that were, at the time he made them, of obsessive interest to academics, critics, and avant-gardists in architecture and out. Principal among these was the idea that architecture must be read, that is, understood, in the same way as a written text.” In terms of our studio, what would a machine be that could “read,” “write,” or “translate” the San Andreas Fault?].

[Images: Daniel Libeskind, Writing Machine (1980s). As Lebbeus Woods has written, describing Libeskind’s work: “Elaborately constructed and enigmatic in purpose, Libeskind’s machines are striking and sumptuous manifestations of ideas that were, at the time he made them, of obsessive interest to academics, critics, and avant-gardists in architecture and out. Principal among these was the idea that architecture must be read, that is, understood, in the same way as a written text.” In terms of our studio, what would a machine be that could “read,” “write,” or “translate” the San Andreas Fault?].

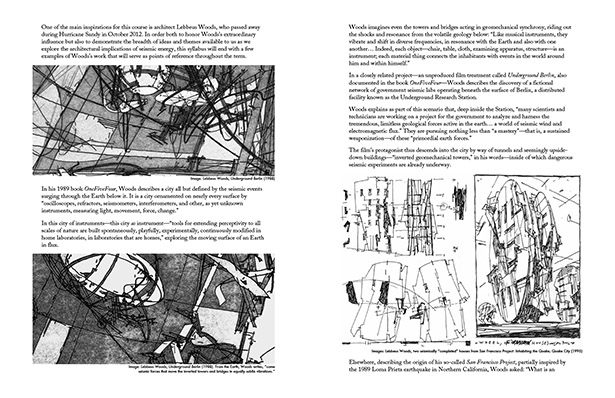

Again, these “instruments” should not be approached as realistic scientific tools, but rather as poetic, spatial augmentations of the San Andreas Fault. Students are being asked to use the problem-solving techniques of architectural design to imagine hypothetical devices at a variety of scales that will translate this unique site—a fault line between tectonic plates and an elastic zone of origin for millions of years of future terrain deformation—into a new kind of spatial and intellectual experience for those who encounter it.

[Images: Harry Partch, various stringed, percussive, and resonating instruments (1940s/1950s)].

[Images: Harry Partch, various stringed, percussive, and resonating instruments (1940s/1950s)].

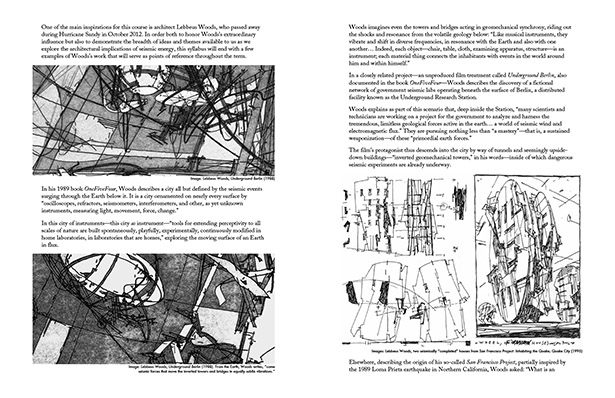

Upon completing these devices, the second, most important, and largest project of the semester, due Wednesday, April 17, will be the San Andreas Fault National Park proposal and its associated Seismic Interpretive Center.

The Seismic Interpretive Center should be an educational facility, equivalent to 30,000 square feet. Here, seismic activity will be studied, demonstrated, interpreted, and otherwise explained to the visiting public and to a seasonal crew of scientist-researchers who use the facility in their work. It might be useful to think of the Seismic Interpretive Center as a direct outgrowth of the instruments developed in the previous project, either by housing or emulating those devices. In other words, the Center could passively display seismic instruments for public use but simultaneously operate as an active, building-scale mechanism for engaging with or tectonically explaining the San Andreas Fault.

In practical terms, the proposed Center should be a fully developed three-dimensional building or landscape project, no matter how speculative or straight-forward its underlying premise might be, whether it is simply a museum of the fault or something more provocative, such as a partially underground public test-facility for generating artificial earthquakes. In all cases—circulation, materials, program, site—students must demonstrate thorough knowledge of their own project in the form of, but not limited to, the appropriate use of plans, sections, elevations, axonometrics, physical models, and 3D diagrams.

[Images: (left) Harry Partch, two instruments, 1940s/1950s. (right) Doug Aitken’s “Sonic Pavilion” (2009), courtesy of the Doug Aitken Workshop].

[Images: (left) Harry Partch, two instruments, 1940s/1950s. (right) Doug Aitken’s “Sonic Pavilion” (2009), courtesy of the Doug Aitken Workshop].

To help develop ideas for the Seismic Interpretive Center, we will look at such precedents as artist Doug Aitken’s “Sonic Pavilion” in Brazil, where, in the words of The New York Times, Aitken “buried microphones sensitive to vibrations caused by the rotation of the planet,” or the artist’s own house in Venice, California, where, again quoting The New York Times, “geological microphones… amplify not just the groan of tectonic plate movements but also the roar of the tides and the rumble of street traffic. Guests can listen in on this subterranean world without putting an ear to the ground. Speakers installed throughout the house bring its metronomic clicks and extended drones to them whenever Aitken turns up the volume.”

More abstractly, students could perhaps think of the Center as a variation on “Solomon’s House,” a proto-scientific research facility featured in Sir Francis Bacon’s 17th-century utopian sci-fi novel The New Atlantis. In Solomon’s House, natural philosophers operate vast, artificial landscapes and complex machines—rivaling anything we read about in Dubai or China today—to examine the world in fantastic detail. Bacon offers a lengthy inventory of the devices available for use: “We have… great and spacious houses where we imitate and demonstrate meteors… We have also sound-houses, where we practice and demonstrate all sounds, and their generation… We have also engine-houses, where are prepared engines and instruments for all sorts of motions… We have also a mathematical house, where are represented all instruments, as well of geometry as astronomy, exquisitely made…”

The larger San Andreas Fault National Park proposal within which this Interpretive Center will sit must include all aspects of an existing park in the National Park Service network of managed sites; however, students must push the National Park typology in new directions, taking seriously the prospect of preserving and framing a landscape that moves.

[Images: (left top) AllesWirdGut Architektur, a Roman quarry in St. Margarethen, Austria, converted into public venue, park, and auditorium, 2006-2008. In a private email, responding to the image seen on the left, landscape blogger Alexander Trevi from Pruned suggested that perhaps it would be more interesting for us to think of the San Andreas Fault not in terms of a detached viewer—like the so-called Rückenfiguren (or figures seen from behind) in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich—but, as Trevi suggested, more like dancer Fred Astaire, physically and whimsically engaging in a choreographed state of delight with the Earth’s shifting topography. (left bottom) “Ice Age Deposits of Wisconsin” (1964) and a photo, taken from Flickr, of an Ice Age National Scenic Trail marker (2007). (right top) National Tourist Route Geiranger-Trollstigen, Norway. Architect: Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter. Photo: Per Kollstad. (right bottom, left to right, top to bottom, within grid) National Tourist Route Rondane. Architect: Carl-Viggo Hølmebakk. Photo: Vegar Moen. National Tourist Route Geiranger-Trollstigen, Norway. Architect: Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter. Photo: Jarle Wæhler. National Tourist Route Aurlandsfjellet. Architect: Todd Saunders / Saunders-Wilhelmsen. Photo: Vegar Moen. National Tourist Route Ryfylke. Architect: Haga Grov / Helge Schjelderup. Photo: Per Kollstad. Courtesy of National Tourist Routes in Norway].

[Images: (left top) AllesWirdGut Architektur, a Roman quarry in St. Margarethen, Austria, converted into public venue, park, and auditorium, 2006-2008. In a private email, responding to the image seen on the left, landscape blogger Alexander Trevi from Pruned suggested that perhaps it would be more interesting for us to think of the San Andreas Fault not in terms of a detached viewer—like the so-called Rückenfiguren (or figures seen from behind) in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich—but, as Trevi suggested, more like dancer Fred Astaire, physically and whimsically engaging in a choreographed state of delight with the Earth’s shifting topography. (left bottom) “Ice Age Deposits of Wisconsin” (1964) and a photo, taken from Flickr, of an Ice Age National Scenic Trail marker (2007). (right top) National Tourist Route Geiranger-Trollstigen, Norway. Architect: Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter. Photo: Per Kollstad. (right bottom, left to right, top to bottom, within grid) National Tourist Route Rondane. Architect: Carl-Viggo Hølmebakk. Photo: Vegar Moen. National Tourist Route Geiranger-Trollstigen, Norway. Architect: Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter. Photo: Jarle Wæhler. National Tourist Route Aurlandsfjellet. Architect: Todd Saunders / Saunders-Wilhelmsen. Photo: Vegar Moen. National Tourist Route Ryfylke. Architect: Haga Grov / Helge Schjelderup. Photo: Per Kollstad. Courtesy of National Tourist Routes in Norway].

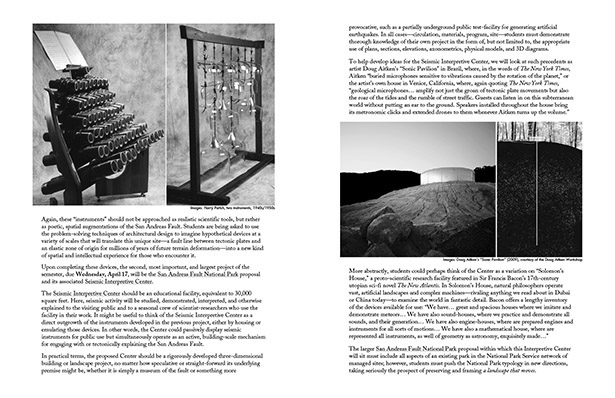

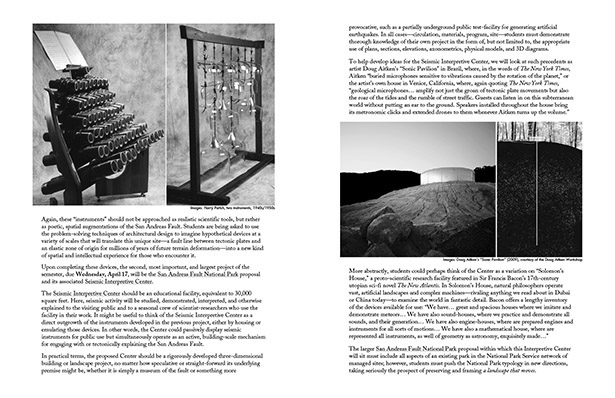

This means students must propose a working combination of such features as trails, lodging, visitors’ centers, educational programming, parking/camping, and other facilities that differentiate National Parks from their less developed counterparts, National Monuments, but with the addition of new types of structures and innovative landscape management techniques that might reveal future opportunities for the U.S. National Park system.

Here, we will look at a variety of precedents, including current plans for a “Manhattan Project National Park” (a National Park that will preserve three geographically diverse sites key to the development of nuclear weapons during World War II); a proposal by photographer Richard Misrach for a “Bravo 20 National Park” (a former U.S. Navy bombing range that would be preserved as a recreational landscape); the High Line here in New York City; an entirely underwater National Park Service “Maritime Heritage Trail” in Biscayne Bay, Florida; the extraordinary, multi-sensory “Taichung Gateway Park” proposal by landscape architects Catherine Mosbach and Philippe Rahm; the “Ice Age National Scenic Trail” in Wisconsin; and, of course, a handful of already existing state parks and recreation areas in California—such as the Los Trancos Open Space Preserve and the 206,000-acre Carrizo Plain National Monument—that feature hiking trails and other recreational facilities that cross the San Andreas Fault.

The “Ice Age National Scenic Trail” is what we might call a planetary interpretive trail: “More than 12,000 years ago,” we read, “an immense flow of glacial ice sculpted a landscape of remarkable beauty across Wisconsin. As the colossal glacier retreated, it left behind a variety of unique landscape features… The Ice Age National Scenic Trail is a thousand-mile footpath—entirely within Wisconsin—that highlights these Ice Age landscape features while providing access to some of the state’s most beautiful natural areas.”

However, no less useful in this context are the “National Tourist Routes” that now criss-cross the geologically rich landscapes of Norway. In essence, these are new scenic routes for automobiles constructed through extraordinary natural landscapes, including coastal fjords and precipitous mountain valleys; however, these routes have also been peppered with signature architectural interventions, including lookout towers, roadside picnic areas, trail infrastructure, geological overlooks, and more.

But how do we define—let alone locate—a park on the scale of a fault line? Landscape architect James Corner suggests that the virtue of a “large park”—which he defines as a park “greater than 500 acres”—is that it “allows for dramatic exposure to the elements, to weather, geology, open horizons, and thick vegetation, all revealed to the ambulant body in alternating sequences of prospect and refuge—distinctive places for overview and survey woven with more intimate spots of retreat and isolation.” He calls such parks “huge experiential reserves”—in terms of the San Andreas, we might say a kind of seismic commons.

Further, thinking about—let alone designing—architecture on this scale requires close attention to what landscape theorist Julia Czerniak calls legibility. “The concept of legibility,” she writes in her edited collection Large Parks, “extends from park design to the design process. In other words, to be realized, parks have to be legible to the people who pay for and use them.” After all, she adds, “in addition to questions of a park’s legibility that stem from recognizing its limits—‘where is the park?’—large park schemes with unconventional configurations provoke other uncertainties—‘how does it look?’ and ‘what can it do?’”

[Images: (left) One of only a few sites where the San Andreas Fault is designated with road signs; photographs by Geoff Manaugh. (right) Satellite view of the San Andreas Fault, rotated 90º (north is to the right)].

[Images: (left) One of only a few sites where the San Andreas Fault is designated with road signs; photographs by Geoff Manaugh. (right) Satellite view of the San Andreas Fault, rotated 90º (north is to the right)].

Complicating matters even more, we will also examine how National Park infrastructure—from interpretive trails to hotels and viewing platforms—function as immersive projects of landscape representation, even above, and possibly rather than, places of embodied physical experience. In other words, as Richard Grusin reminds us in his book Culture, Technology, and the Creation of America’s National Parks, “just as Yellowstone and Yosemite were created as national parks in accordance with late-nineteenth-century assumptions about landscape and representation, so a national park today (whether scenic or historic) must be created according to present-day assumptions about media, culture, and technology.” Indeed, he adds, “national parks have functioned from their inception as technologies for reproducing nature according to the scientific, cultural, and aesthetic practices of a particular historical moment—the period roughly between the Civil War and the end of the First World War.” How, then, would a 21st-century San Andreas Fault National park both represent and preserve the landscape in question?

To help us sort through these many complex questions, and to ease our transition from thinking and designing at the scale of a device or building to the scale of an entire landscape, we will be joined for one class by GSAPP’s Kate Orff, a landscape architect and co-editor of Gateway: Visions for an Urban National Park. Her experience with Gateway will be invaluable for all of us in conceptualizing what a San Andreas Fault National Park might be.

Finally, students must spend the last week of the semester, leading up to our final day of class on Wednesday, April 24, revisiting and refining all of their work produced over the term and, in the process, collecting all of their relevant project documentation. This project documentation will then be collected and published as a small black & white pamphlet, forming a kind of speculative architectural guide to the San Andreas Fault.

In addition to any boards and models necessary for explaining the resulting proposals, this black & white pamphlet will be produced in small quantities for guest critics and other attendees of our final review. It will also be made available to attendees of the GSAPP Year-End Show. Specific requirements—including number of images and length of accompanying descriptive texts—will be discussed during the semester.

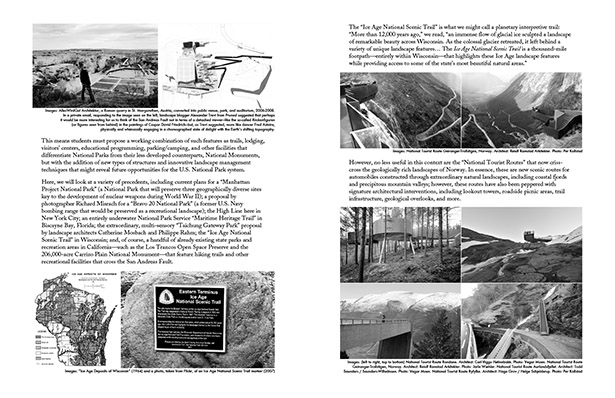

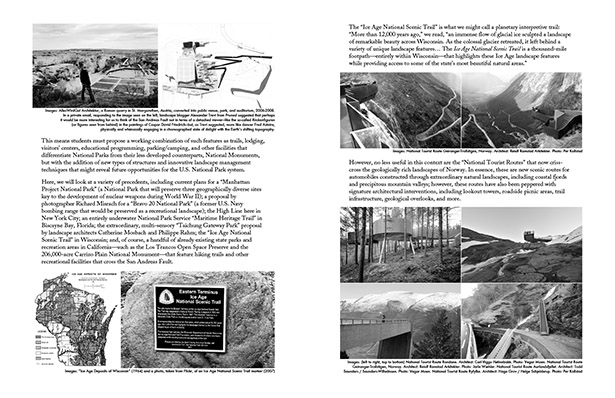

One of the main inspirations for this course is architect Lebbeus Woods, who passed away during Hurricane Sandy in October 2012. In order both to honor Woods’s extraordinary influence but also to demonstrate the breadth of ideas and themes available to us as we explore the architectural implications of seismic energy, this syllabus will end with a few examples of Woods’s work that will serve as points of reference throughout the term.

[Images: (left top and bottom) Lebbeus Woods, from Underground Berlin (1988). From deep inside the Earth, Woods writes, “come seismic forces that move the inverted towers and bridges in equally subtle vibrations.” (right) Lebbeus Woods, two seismically “completed” houses from his San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)].

[Images: (left top and bottom) Lebbeus Woods, from Underground Berlin (1988). From deep inside the Earth, Woods writes, “come seismic forces that move the inverted towers and bridges in equally subtle vibrations.” (right) Lebbeus Woods, two seismically “completed” houses from his San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)].

In his 1989 book OneFiveFour, Woods describes a city all but defined by the seismic events surging through the Earth below it. It is a city ornamented on nearly every surface by “oscilloscopes, refractors, seismometers, interferometers, and other, as yet unknown instruments, measuring light, movement, force, change.”

In this city of instruments—this city as instrument—“tools for extending perceptivity to all scales of nature are built spontaneously, playfully, experimentally, continuously modified in home laboratories, in laboratories that are homes,” exploring the moving surface of an Earth in flux.

Woods imagines even the towers and bridges acting in geomechanical synchrony, riding out the shocks and resonance from the volatile geology below: “Like musical instruments, they vibrate and shift in diverse frequencies, in resonance with the Earth and also with one another… Indeed, each object—chair, table, cloth, examining apparatus, structure—is an instrument; each material thing connects the inhabitants with events in the world around him and within himself.”

In a closely related project—an unproduced film treatment called Underground Berlin, also documented in the book OneFiveFour—Woods describes the discovery of a fictional network of government seismic labs operating beneath the surface of Berlin, a distributed facility known as the Underground Research Station.

Woods explains as part of this scenario that, deep inside the Station, “many scientists and technicians are working on a project for the government to analyze and harness the tremendous, limitless geological forces active in the earth… a world of seismic wind and electromagnetic flux.” They are pursuing nothing less than “a mastery”—that is, a sustained weaponization—of these “primordial earth forces.”

The film’s protagonist thus descends into the city by way of tunnels and seemingly upside-down buildings—“inverted geomechanical towers,” in his words—inside of which dangerous seismic experiments are already underway.

Elsewhere, describing the origin of his so-called San Francisco Project, partially inspired by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in Northern California, Woods asked: “What is an architecture that accepts earthquakes, resonating with their matrix of seismic waves—an architecture that needs earthquakes, and is constructed, transformed, or completed by their effects—an architecture that uses earthquakes, converting to a human purpose the energies they release, or the topographical transformations they bring about—an architecture that causes earthquakes, triggering microquakes in order that ‘the big one’ is defused—an architecture that inhabits earthquakes, existing in their space and time?”

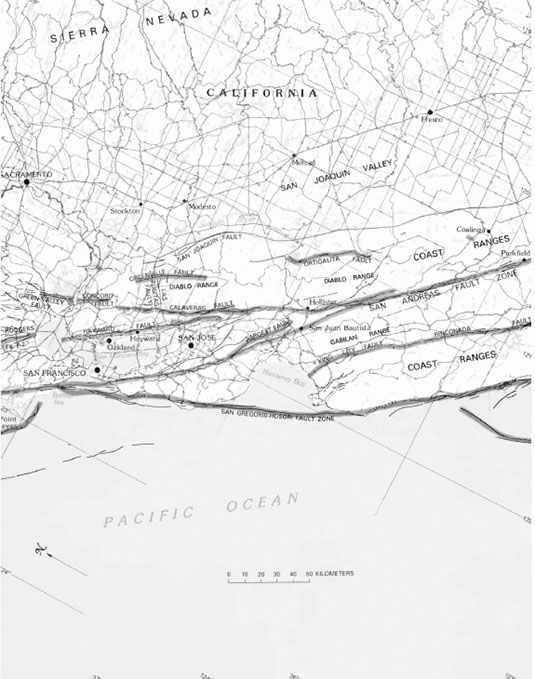

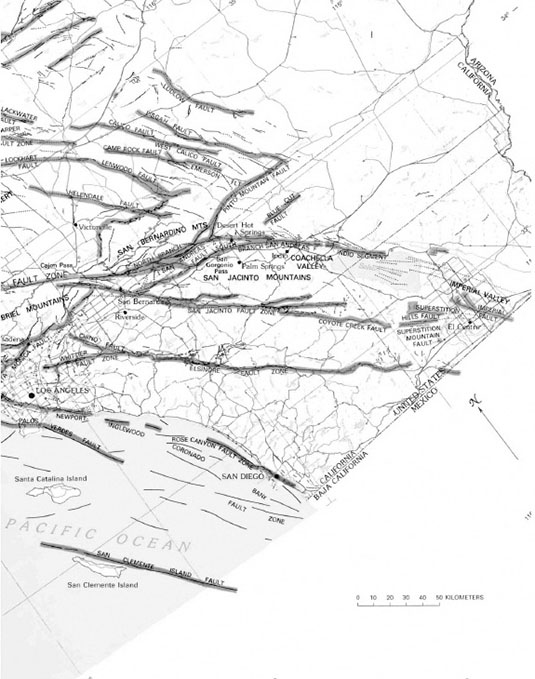

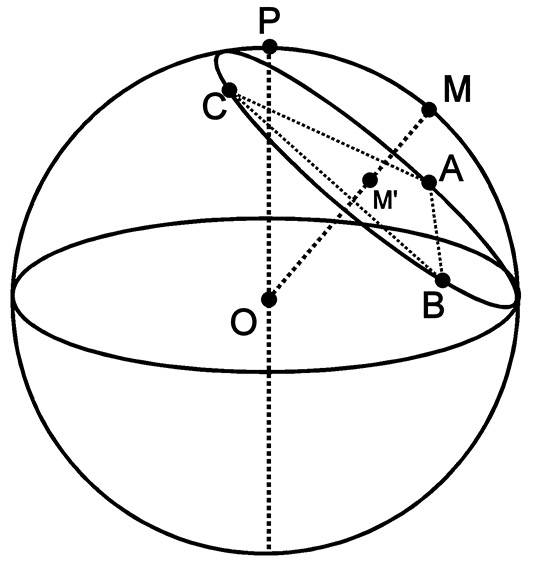

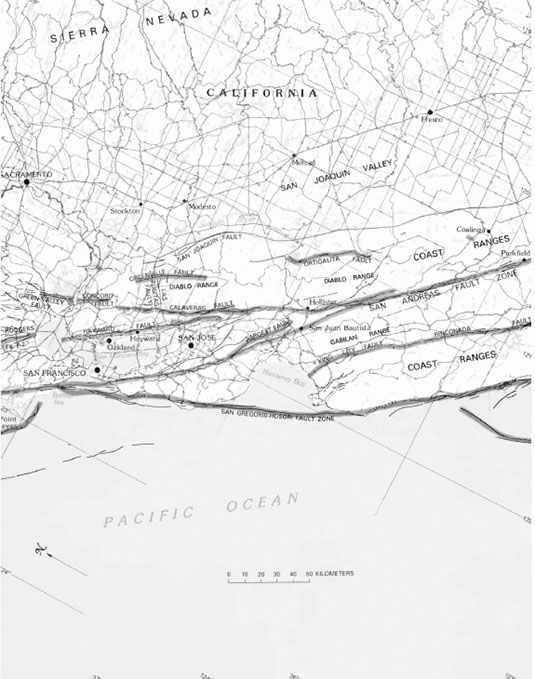

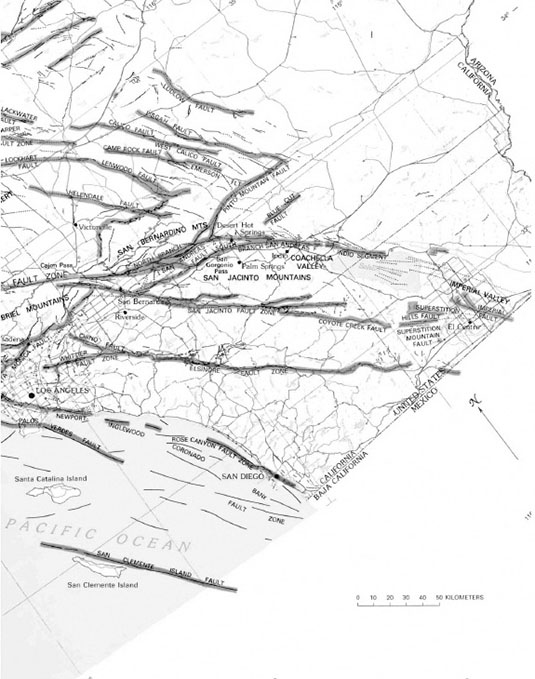

[Image: A map in four sections (see below three images) shows the San Andreas Fault stretching from northern to southern California. The San Andreas “is just one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes,” paleontologist Richard Fortey writes in Earth: An Intimate History. It is “the flagship of a fleet of faults that run close to the western edge of North America… In places, maps of the interweaving faults look more like a braided mesh than the single, deep cut of our imagination.” Here, we see the San Andreas come to an end in Northern California at the so-called Mendocino Triple Junction. Maps courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF); see original paper for higher resolution].

[Image: A map in four sections (see below three images) shows the San Andreas Fault stretching from northern to southern California. The San Andreas “is just one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes,” paleontologist Richard Fortey writes in Earth: An Intimate History. It is “the flagship of a fleet of faults that run close to the western edge of North America… In places, maps of the interweaving faults look more like a braided mesh than the single, deep cut of our imagination.” Here, we see the San Andreas come to an end in Northern California at the so-called Mendocino Triple Junction. Maps courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF); see original paper for higher resolution].

Readings & References

Online (Required Reading)

USGS Earthquake Hazards Program:

earthquake.usgs.gov

The San Andreas Fault System, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1515:

pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1990/1515/pp1515.pdf

The San Andreas Fault:

pubs.usgs.gov/gip/earthq3/contents.html

“San Andreas System and Basin and Range,” from Active Faults of the World by Robert Yeats (Cambridge University Press):

dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139035644.004

Where’s the San Andreas Fault? A Guidebook to Tracing the Fault on Public Lands in the San Francisco Bay Region:

pubs.usgs.gov/gip/2006/16/gip-16.pdf

Of Mud Pots and the End of the San Andreas Fault:

seismo.berkeley.edu/blog/seismoblog.php/2008/11/04/of-mud-pots-and-the-end-of-the-san-andre

U.S. Geological Survey Fault and Volcano Monitoring Instruments:

earthquake.usgs.gov/monitoring/deformation/data/instruments.php

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF)].

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF)].

Online (Reference Only)

California Integrated Seismic Network and Southern California Seismic Network:

cisn.org | www.scsn.org

California Strong Motion Instrumentation Program:

conservation.ca.gov/cgs/smip/Pages/about.aspx

California Geotour Online Geologic Field Trip:

conservation.ca.gov/cgs/geotour/Pages/Index.aspx

Carrizo Plain National Monument maps and brochures:

blm.gov/ca/st/en/fo/bakersfield/Programs/carrizo/brochures_and_maps.html

Ken Goldberg, Mori and Ballet Mori:

memento.ieor.berkeley.edu | goldberg.berkeley.edu/art/Ballet-Mori

Doug Aitken, Sonic Pavilion:

dougaitkenworkshop.com/work/sonic-pavilion

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF)].

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF)].

Offline (Required Reading)

Smout Allen, Pamphlet Architecture 28: Augmented Landscapes (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)

Ethan Carr, Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service (University of Nebraska Press, 1999) — Introduction, Chapter 1, and Chapter 4

Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves, eds., Large Parks (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007) — Foreword, Introduction, and Chapter Seven

Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (Architectural Association, 1997)

Richard Fortey, Earth: An Intimate History (Vintage, 2004) — Chapter 9: “Fault Lines”

John McPhee, Assembling California (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1993)

David L. Ulin, The Myth of Solid Ground: Earthquakes, Prediction, and the Fault Line Between Reason and Faith (Penguin, 2004) — “The X-Files,” “A Brief History of Seismology,” and “Earthquake Country” (though entire book is recommended)

Lebbeus Woods, OneFiveFour (Princeton Architectural Press, 1989)

Offline (Reference Only)

Alexander Brash, Jamie Hand, and Kate Orff, eds., Gateway: Visions for an Urban National Park (Princeton Architectural Press, 2011)

C. J. Lim, Devices: A Manual of Architectural + Spatial Machines (Elsevier/Architectural Press, 2006)

Lebbeus Woods, Radical Reconstruction (Princeton Architectural Press, 2001) — “Radical Reconstruction” (pp. 13-31) and “San Francisco” (p. 133-155)

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF)].

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (PDF)].

Film and Games (Entertainment Value Only!)

A View To A Kill, dir. John Glen (1985)

Fracture, LucasArts (2008)

Music (Required Listening)

Our work this Spring will be paralleled by a series of musical experiments led by Bay Area sound artist Marc Weidenbaum’s Disquiet Junto, an online music collective. The Disquiet Junto will be developing projects that explore the sonic properties of the San Andreas Fault and uploading the results of these seismic-acoustic experiments to Soundcloud. Students will be required to leave comments on these audio tracks as part of regular homework over the course of the Spring term.

The Disquiet Junto, a satellite operation of disquiet.com, “uses formal restraint as a springboard for creativity. In 2012, the year it launched, the Disquiet Junto produced over 1,600 tracks by over 270 musicians from around the world. Disquiet.com has operated at the intersection of sound, art, and technology since 1996.”

[Image: (left) A Rückenfigur looks at a highway cut through the San Andreas Fault in Palmdale, southern California; photograph by Nicola Twilley. (right) Aerial rendering of the San Andreas Fault, courtesy of NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (2000). If an earthquake presents us with a turbulent condition similar to waves in the ocean or a storm at sea, is the ship a more appropriate structural metaphor than the building—even if it’s an ocean that only exists for sixty seconds? What does orientation mean for the minute-long intensity of an earthquake—the becoming-ocean of land—and how do we learn to navigate a planet that acts like the sea?].

[Image: (left) A Rückenfigur looks at a highway cut through the San Andreas Fault in Palmdale, southern California; photograph by Nicola Twilley. (right) Aerial rendering of the San Andreas Fault, courtesy of NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (2000). If an earthquake presents us with a turbulent condition similar to waves in the ocean or a storm at sea, is the ship a more appropriate structural metaphor than the building—even if it’s an ocean that only exists for sixty seconds? What does orientation mean for the minute-long intensity of an earthquake—the becoming-ocean of land—and how do we learn to navigate a planet that acts like the sea?].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes]. [Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Image: Screen grab from Nocturnes].

[Images: Paintings by Eric Merrell; screen grabs from Nocturnes].

[Images: Paintings by Eric Merrell; screen grabs from Nocturnes].

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: An otherwise unrelated shot of rebar used in road construction; via

[Image: An otherwise unrelated shot of rebar used in road construction; via

[Image: A curb in Hayward reveals how much the ground is drifting due to “fault creep”: the red-painted part is slowly, but relentlessly, moving north. Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: A curb in Hayward reveals how much the ground is drifting due to “fault creep”: the red-painted part is slowly, but relentlessly, moving north. Photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: “Fault creep” bends the curbs in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “Fault creep” bends the curbs in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: 359 Locust Avenue, Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: 359 Locust Avenue, Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: The walkway is slowly creeping north, no longer centered with the house it leads to; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: The walkway is slowly creeping north, no longer centered with the house it leads to; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: The Calaveras Fault pushes its way through Hollister; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: The Calaveras Fault pushes its way through Hollister; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: A fault-buckled wall and sidewalk bearing traces of planetary forces below; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: A fault-buckled wall and sidewalk bearing traces of planetary forces below; photos by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: A curb and street drain popped far out of alignment in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: A curb and street drain popped far out of alignment in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Images: Crossing onto the Pacific Plate (heading west) in Parkfield; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: Crossing onto the Pacific Plate (heading west) in Parkfield; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Looking east at the North American Plate in Parkfield; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Looking east at the North American Plate in Parkfield; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: A moving curb becomes an inadvertent compass for measuring seismic energy in Hayward; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: A moving curb becomes an inadvertent compass for measuring seismic energy in Hayward; photos by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Haphazard concrete patchwork in a formerly straight sidewalk betrays the slow action of fault creep; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Haphazard concrete patchwork in a formerly straight sidewalk betrays the slow action of fault creep; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: A fault-caused grassy knoll rises in the center of Dunne Park in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: A fault-caused grassy knoll rises in the center of Dunne Park in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, via

[Image: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, via

[Image: The “

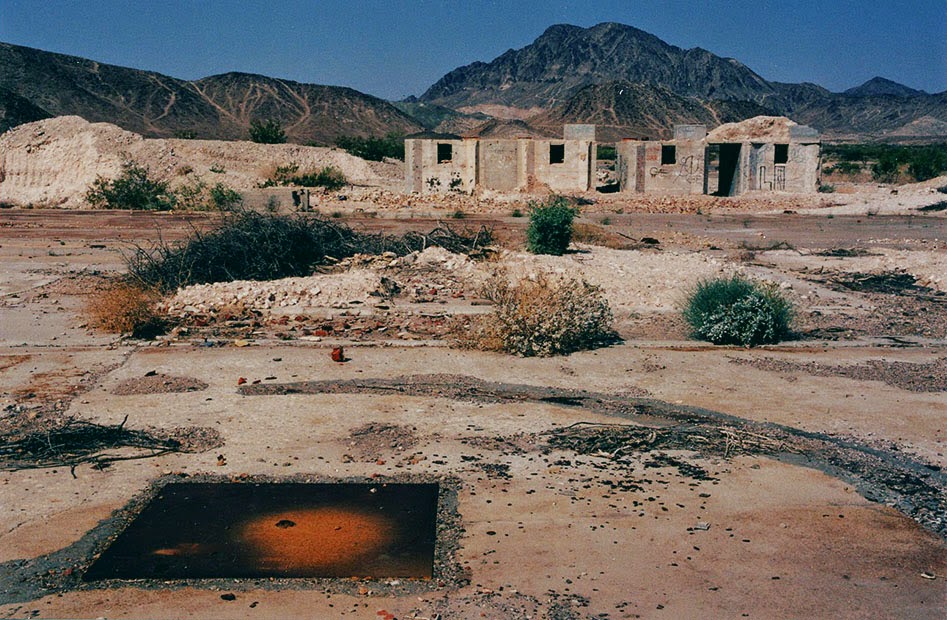

[Image: The “ [Image: Midland, California, via

[Image: Midland, California, via  [Image: Midland, California, via

[Image: Midland, California, via  [Image: The abandoned streets of

[Image: The abandoned streets of  [Image: Midland, California, via

[Image: Midland, California, via

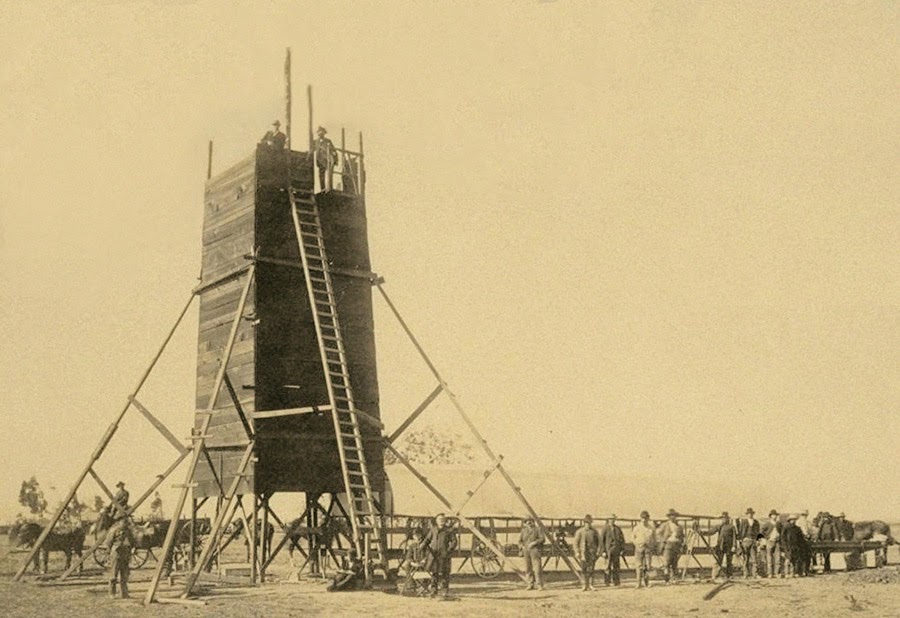

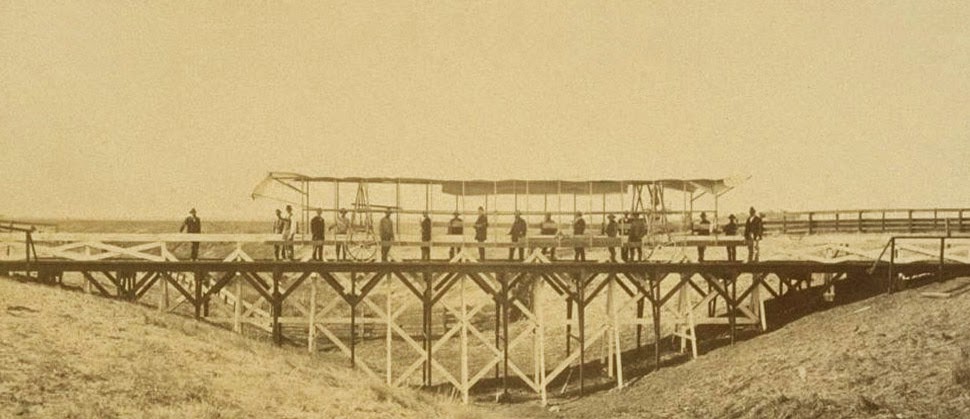

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.

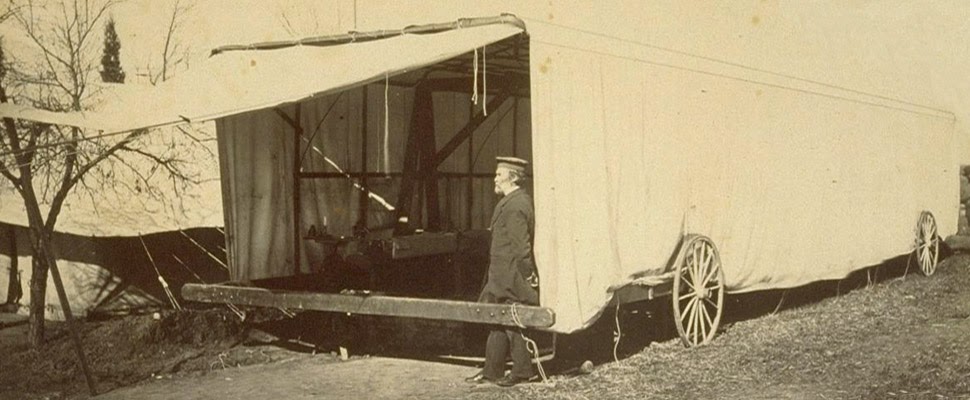

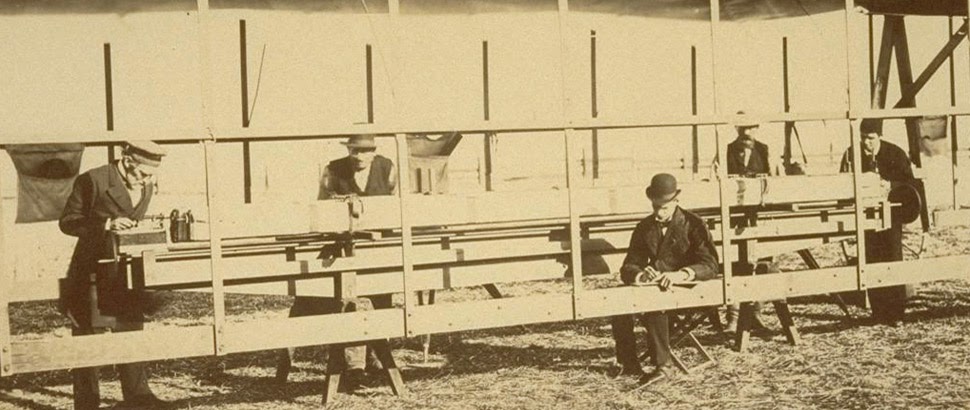

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.  The “moveable tent or ‘

The “moveable tent or ‘ The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the  In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.  That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land. Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Construction work at a future Amazon.com warehouse in San Bernardino, courtesy of

[Image: Construction work at a future Amazon.com warehouse in San Bernardino, courtesy of  [Image: An unrelated warehouse photo from

[Image: An unrelated warehouse photo from  [Image: A laser-leveling target used for calibrating car scales, taken by someone named “

[Image: A laser-leveling target used for calibrating car scales, taken by someone named “

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)]. [Images: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995) and an aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, looking south across the Carrizo Plain at approximately +35° 6′ 49.81″, -119° 38′ 40.98″].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995) and an aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, looking south across the Carrizo Plain at approximately +35° 6′ 49.81″, -119° 38′ 40.98″]. [Images: (left) A “fault trench” cut along the San Andreas for studying underground seismic strain; photo by Ricardo DeAratanha for the Los Angeles Times. (right) A property fence “offset” nearly eight feet by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; a similar fence is now part of an “

[Images: (left) A “fault trench” cut along the San Andreas for studying underground seismic strain; photo by Ricardo DeAratanha for the Los Angeles Times. (right) A property fence “offset” nearly eight feet by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; a similar fence is now part of an “ [Images: (left) John Braund, Cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, March 1939, demonstrates a “new process expected to revolutionize map making… showing all the details of topography in a form true to nature.” His machine chisels topographic details using “a specially-designed electric hammer.” What new mapping devices might be possible for the San Andreas Fault, for a landscape unpredictably on the move? (right top) From Piano Tuning by J. Cree Fischer (1907). (right bottom) Bernard Tschumi, Parc de la Villette, Paris (1989). Can—or how do—we extract a site-logic from the San Andreas Fault itself?].

[Images: (left) John Braund, Cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, March 1939, demonstrates a “new process expected to revolutionize map making… showing all the details of topography in a form true to nature.” His machine chisels topographic details using “a specially-designed electric hammer.” What new mapping devices might be possible for the San Andreas Fault, for a landscape unpredictably on the move? (right top) From Piano Tuning by J. Cree Fischer (1907). (right bottom) Bernard Tschumi, Parc de la Villette, Paris (1989). Can—or how do—we extract a site-logic from the San Andreas Fault itself?]. [Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)]. [Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)]. [Images: D.V. Rogers,

[Images: D.V. Rogers,  [Images: Daniel Libeskind,

[Images: Daniel Libeskind,  [Images:

[Images:  [Images: (left)

[Images: (left)  [Images: (left top)

[Images: (left top)  [Images: (left) One of only a few sites where the San Andreas Fault is designated with road signs; photographs by Geoff Manaugh. (right) Satellite view of the San Andreas Fault, rotated 90º (north is to the right)].

[Images: (left) One of only a few sites where the San Andreas Fault is designated with road signs; photographs by Geoff Manaugh. (right) Satellite view of the San Andreas Fault, rotated 90º (north is to the right)]. [Images: (left top and bottom) Lebbeus Woods, from

[Images: (left top and bottom) Lebbeus Woods, from  [Image: A map in four sections (see below three images) shows the San Andreas Fault stretching from northern to southern California. The San Andreas “is just one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes,” paleontologist Richard Fortey writes in

[Image: A map in four sections (see below three images) shows the San Andreas Fault stretching from northern to southern California. The San Andreas “is just one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes,” paleontologist Richard Fortey writes in  [Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 ( [Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 ( [Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 ( [Image: (left) A

[Image: (left) A

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The “Electric Aurora,” from Specimens of Unnatural History, by

[Image: The “Electric Aurora,” from Specimens of Unnatural History, by  Finally, Nicola and I will fall out of the car in a state of semi-delirium in La Jolla, California, where I’ll be presenting at a 2-day symposium on

Finally, Nicola and I will fall out of the car in a state of semi-delirium in La Jolla, California, where I’ll be presenting at a 2-day symposium on