[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

I wanted to give a quick heads up that a new collaborative exhibition will be opening to the public later today in the Doheny Memorial Library at USC here in Los Angeles, featuring work by myself and Smout Allen.

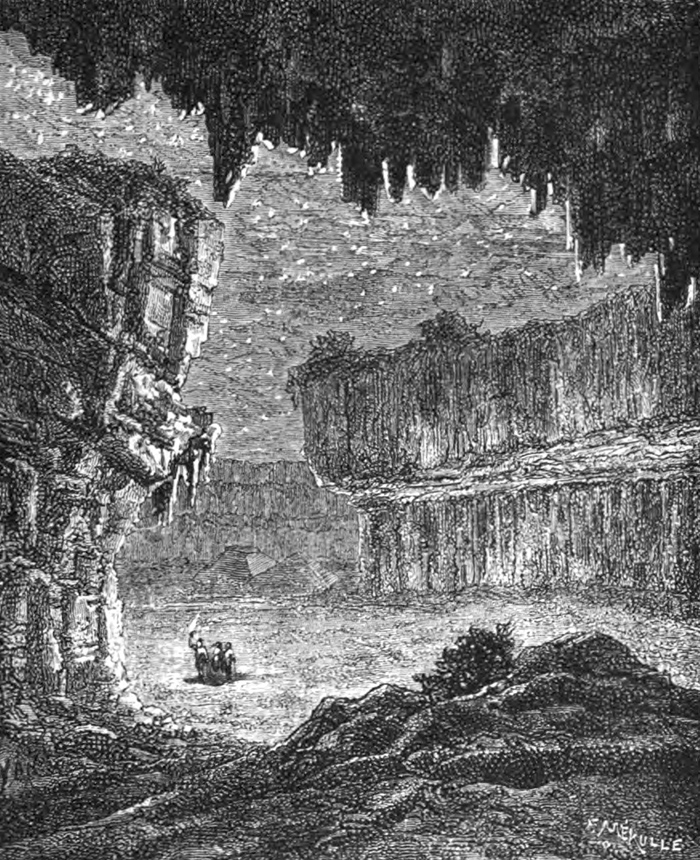

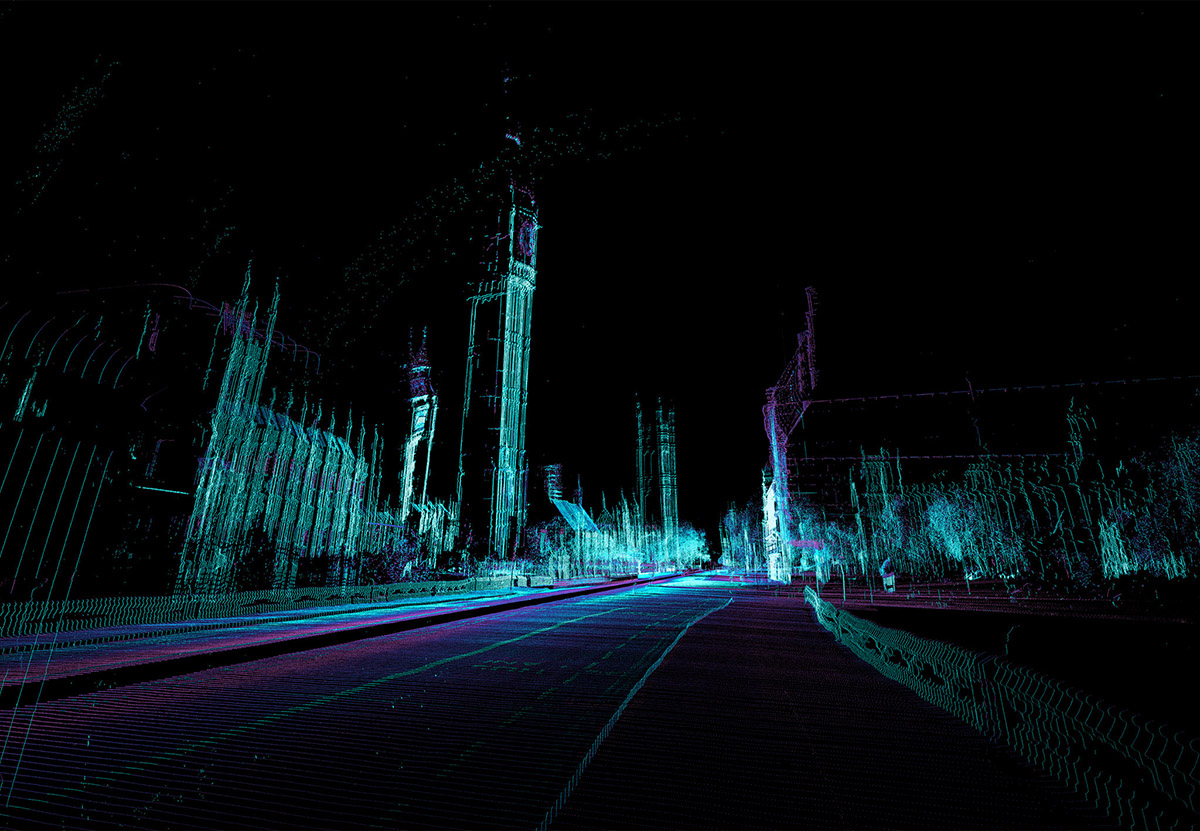

Called L.A.T.B.D., the project looks at diverse narrative, scientific, architectural, and landscape futures of Los Angeles. It is a city always yet to be determined—or L.A., T.B.D.

The exhibition actually comes at the very end of the 2015 USC Libraries Discovery Fellowship, which I’ve had the honor of holding this year, the challenge of which was to use the archival holdings of USC as a springboard for looking forward toward whatever Los Angeles might become.

Like plotting a ballistic trajectory, if we know where L.A. has been—if we can see the ingredients of its past, from its prehuman landscapes to the 2012 procession of the Space Shuttle—can we determine where the city might be, 10, 20, 100 years from now?

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

The overall curatorial idea was that, hidden within USC’s impressive and seemingly endless archival holdings, there might be glimpses of an L.A. yet to come, and that a project such as this should find a way of bringing that future version of the city into focus.

However, not one for prediction or prescriptive visions of tomorrow, I wanted this to be far more open-ended than that. We thus developed several parallel lines of materials for the show.

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

One, of course, are a series of gorgeous models designed and fabricated by Smout Allen, showing various hypothetical scenarios for the future city. In one, huge pendulums have been installed beneath the streets to act as seismic counterweights, protecting the city from earthquakes.

In another, the titanic forces released by plate tectonics can be captured by a new kind of power station, converting those otherwise threatening movements of the earth into a source of renewable energy.

In yet another, the city’s freeway system has been converted into a kind of immersive astronomical device, to help train the eyes of this city of stars on an older and more important firmament above.

This work also served as a direct source for the related project we did for this year’s inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial.

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by Smout Allen for USC Libraries; photo by Stonehouse Photographic].

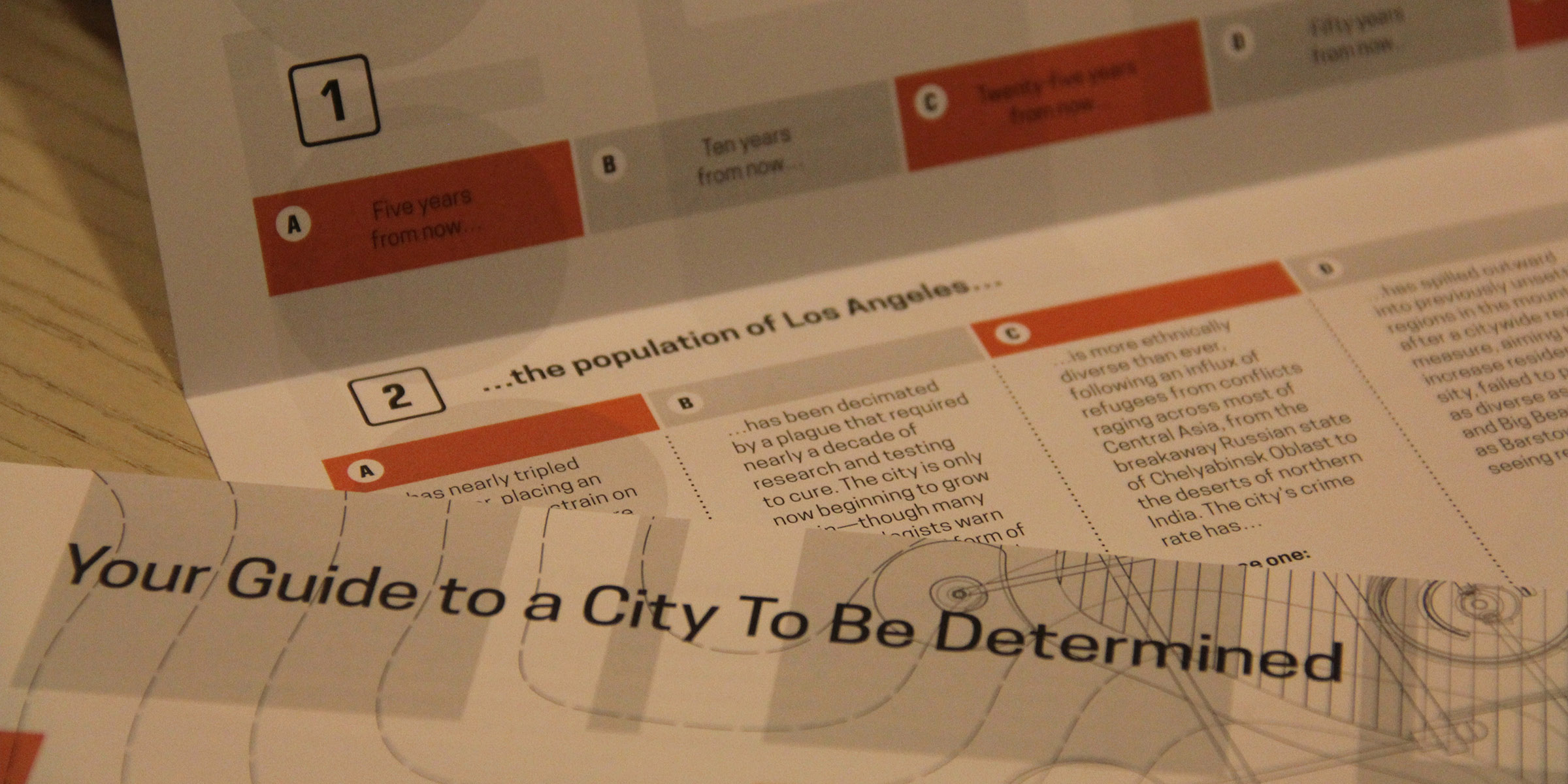

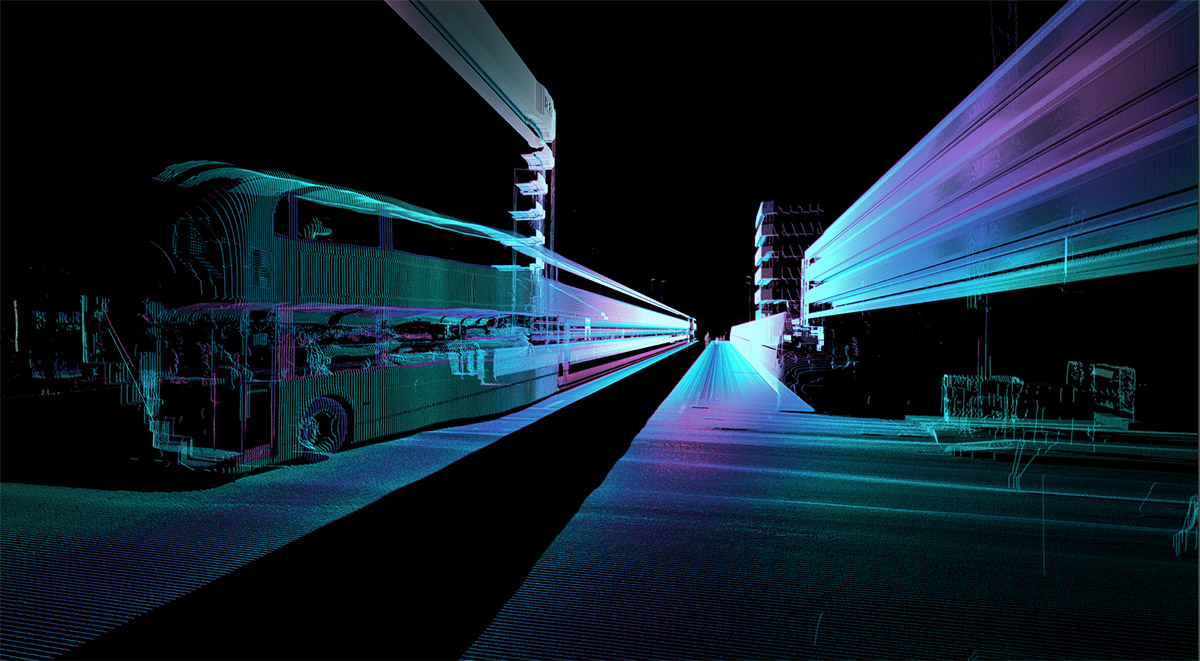

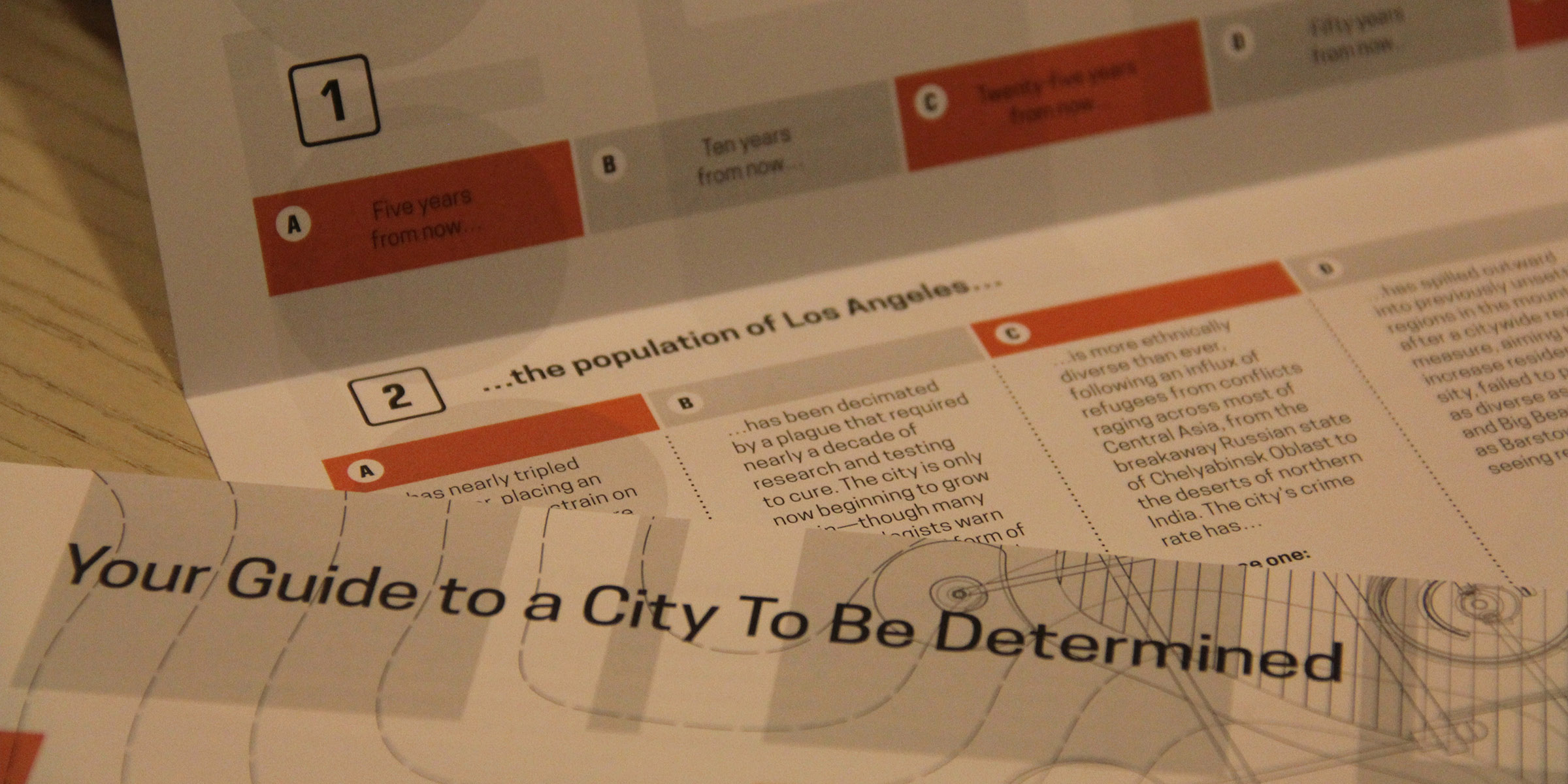

Another key part of the L.A.T.B.D. exhibition is an interactive text that allows visitors to, in a sense, choose their own future for the metropolis. This text combines a small-scale look at what sort of Los Angeles might yet greet our unborn descendants—complete with neighborhoods flooded by sea-level rise, widespread demographic shifts, and corrupt political machinations—with a subtext of noir or urban mystery.

Put another way, if this is a city known for its conspiracies and crimes—whether it’s Chinatown, O.J. Simpson, bank heists, or the novels of James Ellroy—can we use that same narrative register to explore the city’s future infrastructure?

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by David Mellen Design; terrible photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by David Mellen Design; terrible photos by Geoff Manaugh].

I started referring to this as a kind of architectural or infrastructural noir, and I’ve come to really like the phrase: the accompanying exhibition text is thus not at all what you’d expect to see in a typical gallery setting, but instead tells an endlessly branching “noir” about the next Los Angeles—by, in some ways, revealing what Los Angeles really was, all along.

[Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by David Mellen Design; terrible photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by David Mellen Design; terrible photo by Geoff Manaugh].

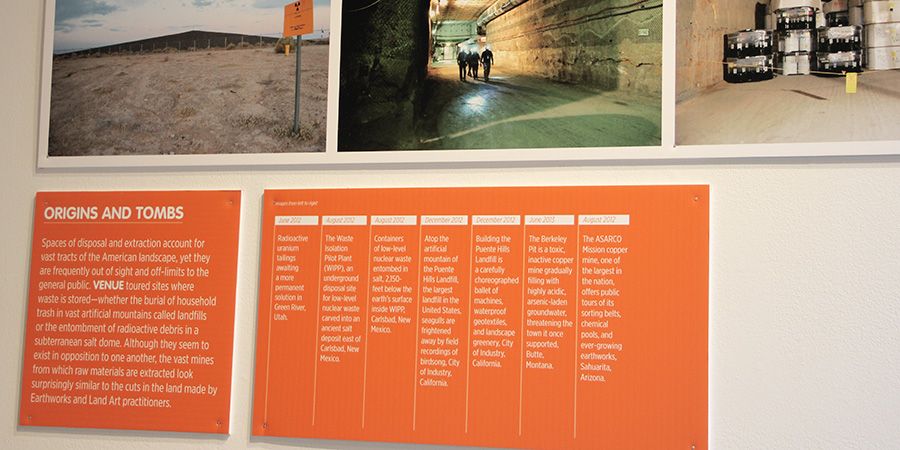

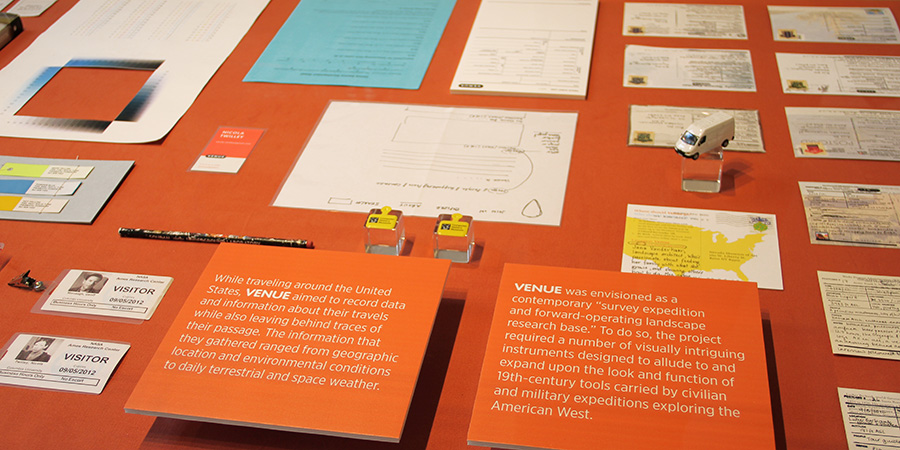

Finally, the exhibition includes a series of historical artifacts from the USC Libraries holdings, from old scientific reports to transportation policy papers, from obsolete urban predictions from the 1980s to board games set in a premodern L.A.

Here, working with designer David Mellen, we had a lot of fun, deliberately crossing and recrossing the line between fiction and reality: that is, not every artifact you see in the exhibition should be trusted, and things might not always be what they seem.

There’s much more to say about the exhibition, but I wanted to get a quick post up before the show opens later this afternoon. There is a reception tonight at 5:30pm in the library, or consider stopping by on Saturday, October 17, from noon to 1pm, to talk to myself and Smout Allen about the project. Saturday’s event is part of the “Archives Bazaar.”

L.A.T.B.D. was made possible by support from the USC Libraries Discovery Fellowship, the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, and the British Council. Special thanks are owed to Dean Catherine Quinlan; to Jeff Watson; to the USC Libraries staff; and to Harry Grocott, Doug Miller, and Sandra Youkhana.

[Image: From Pierre Huyghe, “Les grandes ensembles” (2001)].

[Image: From Pierre Huyghe, “Les grandes ensembles” (2001)].

[Image: Shelters by

[Image: Shelters by  [Image: Shelters by

[Image: Shelters by  [Image: Shelters by

[Image: Shelters by  [Image: Shelters by

[Image: Shelters by

[Images: Shelters by

[Images: Shelters by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by

[Image: The “Barakka Lift” in Malta; photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Descending into Mammoth Cave, from

[Image: Descending into Mammoth Cave, from  [Image: A room in Mammoth Cave known as “The Maelstrom,” from

[Image: A room in Mammoth Cave known as “The Maelstrom,” from  [Image: A vast underground room filled with “a silent, terrible solitude,” from

[Image: A vast underground room filled with “a silent, terrible solitude,” from  [Image: An unfortunately rather low-res image from

[Image: An unfortunately rather low-res image from

[Image by

[Image by  [Image by

[Image by

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D. by

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Images: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by  [Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Image: L.A.T.B.D.‘s accompanying exhibition text, designed by

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Instruments

[Image: Instruments  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: An only conceptually related photo

[Image: An only conceptually related photo

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, courtesy of the  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Stela fragment of Horiaa,” courtesy of the  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of the “Coffin of Tpaeus,” courtesy of the