[Image: Proposal for the Stockholm Public Library by Olivier Charles].

[Image: Proposal for the Stockholm Public Library by Olivier Charles].

The “Books Received” series on BLDGBLOG continues apace, with short descriptions of interesting—but not necessarily new–books that have passed through the home office here. In all cases, these are books about architecture, landscape, and the built environment, albeit in an extended sense, encompassing paleontology, marine biophysics, space archaeology, geopolitics, infrastructural anthropology, museology, how-to guides for architectural design, and more.

Note, however, that these lists will always include books that I have not read in full—and the present rundown is no exception.

1) The Docks by Bill Sharpsteen (University of California Press).

2) Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them by Donovan Hohn (Viking).

3) On Roads: A Hidden History by Joe Moran (Profile Books).

Three books about infrastructure and the humans (and plastic ducks) who inhabit it, from the docks of Long Beach to accidents at sea supplying an unexpected way to trace global trade networks, to a short history of the roads by which civilization is now defined.

4) Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology, and Heritage edited by Ann Garrison Darrin and Beth Laura O’Leary (CRC Press).

4) Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology, and Heritage edited by Ann Garrison Darrin and Beth Laura O’Leary (CRC Press).

The Handbook is an endlessly fascinating mega-collection (1,015+ pages!) of essays about the science of space archaeology: the study and preservation of artifacts and sites related to human space exploration, including “everything from launch pads to satellites to landers on Mars.” Lost spacecraft, failed missions, “graveyard orbits,” and the Apollo 11 landing site all make extended appearances in the book, interpreted as examples of the space-archaeological record. “For example,” we read, “the location of one human footprint on the Moon in situ is an archaeological feature that defines one of the ultimate events of humankind and is a part of the physical and temporal record of all the engineering research and development that made it possible.”

The book is full of amazing factoids—we learn, for example, that, “Surprisingly, the Viking 1 lander, which remains on Mars, is considered part of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum,” suggesting a distributed, inter-planetary museum of inaccessible earthly objects—and eye-popping new fields of study, such as “the role archaeologists might play in understanding the material culture of extraterrestrials or other intelligent species, once the physical evidence is scientifically verifiable.” The book even describes a kind of computational archaeology, by which “the heritage created by robots in the form of their artificial intelligence” would be both studied and preserved.

5) Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas by Stefan Helmreich (University of California Press).

Alien Ocean is an anthropological study of oceanographers, marine biologists, genetic researchers, and the way that they perform research, not an oceanographic study in itself. But if the idea of following a Donna Haraway-like narrator around the California coast, visiting gene-research labs, riding down in submarines, and opining about the chemical possibilities of life on other planets, where strange maritime organisms might swim through the dark currents of “extraterrestrial seas,” then you’ll find Helmreich’s book as hard to put down as I did.

6) The Planet in a Pebble: A Journey into Earth’s Deep History by Jan Zalasiewicz (Oxford University Press).

Jan Zalasiewicz, author of The Earth After Us: What Legacy Will Humans Leave in the Rocks?, is back with this book-length thought experiment: can the entire geological history of the planet be deduced from a single pebble? If so, what tools—what pieces of equipment and what scientific ideas—would you need at your disposal, and what might you find in the process?

7) The Alphabet and the Algorithm by Mario Carpo (MIT).

7) The Alphabet and the Algorithm by Mario Carpo (MIT).

8) The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture by Pier Vittorio Aureli (MIT).

9) The Liberal Monument: Urban Design and the Late Modern Project by Alexander D’Hooge (Princeton Architectural Press).

MIT’s “Writing Architecture” series continues with two new titles influenced by Peter Eisenman. In one, Mario Carpo explores mechanical reproduction, robotics, and the historical status of the architectural copy (see also the recent book Anachronic Renaissance for a fascinating discussion of architectural duplication). In the other, Pier Vittorio Aureli dives into the political, in its most literal sense: where architecture intervenes in, and actively confronts, the city, the polis. Here, Aureli draws an interesting distinction between “the political dimension of coexistence (the city)” and “the economic logic of social management (urbanization).”

Finally, Alexander D’Hooge uses this expanded publication of his Ph.D. thesis to propose “a series of civic complexes” built within “the existing, vast net of suburban sprawl” that surrounds the contemporary city, in order to introduce public space and institutional communality “in a territory otherwise devoid of it.”

10) Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar, and Nicosia by Jon Calame and Esther Charlesworth, with a foreword by Lebbeus Woods (University of Pennsylvania Press).

10) Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar, and Nicosia by Jon Calame and Esther Charlesworth, with a foreword by Lebbeus Woods (University of Pennsylvania Press).

11) Walled States, Waning Sovereignty by Wendy Brown (ZONE Books).

12) A Wall in Palestine by René Backmann (Picador).

Three books about walls: architecture and urbanism used to separate and to neutralize the lives of a city’s human residents, not to catalyze vibrant communities or to bring neighboring people together.

As Jon Calame and Esther Charlesworth conclude in Divided Cities, “divided cities are not aberrations. Instead, they are the unlucky vanguard of a large and growing class of cities.” Indeed, the authors add, “Evidence gleaned from the five cities examined here suggests that, given similar circumstances and pressures, any city could undergo a comparable metamorphosis,” leading to the “dangerous, wasted spaces” of urban partition. The book includes several highly memorable images, including a sewage treatment system in the divided city of Nicosia, Cyprus—a subterranean network “where all the sewage from both sides of the city is treated.” A waste-management engineer quips that “the city is divided above ground but unified below.” It is a kind of infrastructural conjoined twin.

Wendy Brown—in what is ultimately a highly repetitive book that would have been more effective as an essay—suggests that the ongoing construction boom in border walls and other peripheral fortifications is actually a panicked response to the loss of power on behalf of the nation-state, not architectural proof that the nation-state has experienced a sovereign renaissance. “Thus,” she writes, “walls generate what Heidegger termed a ‘reassuring world picture’ in a time increasingly lacking the horizons, containment, and security that humans have historically required for social and psychic integration and for political membership.”

René Backmann’s much more journalistic Wall in Palestine follows the cultural, economic, religious, and psychological effects of the Israeli border fence, as Backmann walks its complicated routes often cutting straight through previously thriving Palestinian villages.

13) A Landscape Manifesto by Diana Balmori (Yale University Press).

13) A Landscape Manifesto by Diana Balmori (Yale University Press).

14) Above the Pavement—The Farm! Architecture & Agriculture at PF1 edited by Amale Andraos and Dan Wood (Princeton Architectural Press).

15) L.A. Under the Influence: The Hidden Logic of Urban Property by Roger Sherman (University of Minnesota Press).

Exploring complex intersections where the city hits the land it’s built upon and both are irrevocably transformed, these three books take notably different rhetorical tones. From Balmori’s 25-point “manifesto” (#18: “Emerging landscapes are becoming brand-new actors on the political stage”) to the hands-on field notes of Work AC’s Public Farm 1, by way of Roger Sherman’s real-estate-based spatial survey of Los Angeles and the various rights of land access and title that financially define the ground of the modern metropolis, each of these books offers surprising suggestions for formal projects and future research. Above the Pavement also benefits from a great design by Project Projects.

16) The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia by James C. Scott (Yale University Press).

16) The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia by James C. Scott (Yale University Press).

17) Utopics: Systems and Landmarks edited by Simon Lamunière (JRP/Ringier).

18) Rage and Time: A Psychopolitical Investigation by Peter Sloterdijk (Columbia University Press).

19) Violence Taking Place: The Architecture of the Kosovo Conflict by Andrew Herscher (Stanford University Press).

These four books take an explicitly political approach to space and geography, including Peter Sloterdijk’s suggestion that rage is an underappreciated force of political motivation, one that can be traced back to the mythological origins of the European psyche, and Simon Lamunière’s edited catalog of utopian ideas and spaces.

James Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed, meanwhile, is one of the most stimulating books I’ve read in the past six months. Scott writes about a region called “Zomia,” which encompasses “virtually all the lands at altitudes above roughly three hundred meters all the way from the Central Highlands of Vietnam to northeastern India and traversing five Southeast Asian nations (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Burma) and four provinces of China (Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and parts of Sichuan). It is an expanse of 2.5 million square kilometers containing about one hundred million minority peoples of truly bewildering ethnic and linguistic variety.”

Scott explores how certain agricultural practices go hand-in-hand with “state-making projects”—and, conversely, how different forms of food cultivation, land management, and foraging offer what Scott calls “escape value.” That is, they allow for “state evasion”: spatial and agricultural techniques for “steering clear of being politically captured” by an empire or nation-state. “Far from being ‘left behind’ by the progress of civilization in the valleys,” Scott writes, “[the people of Zomia] have, over long periods of time, chosen to place themselves out of the reach of the state… There, they practiced what I will call escape agriculture: forms of cultivation designed to thwart state appropriation. Even their social structure could fairly be called escape social structure inasmuch as it was designed to aid dispersal and autonomy and to ward off political subordination.”

Given time, I hope to post about Scott’s book at greater length later this year; it is highly recommended.

20) Form+Code in Design, Art, and Architecture by Casey Reas, Chandler McWilliams, and LUST (Princeton Architectural Press).

20) Form+Code in Design, Art, and Architecture by Casey Reas, Chandler McWilliams, and LUST (Princeton Architectural Press).

21) Architectural Drawing by David Dernie (Laurence King Publishing).

22) Architectural Modelmaking by Nick Dunn (Laurence King Publishing).

All three of these books are useful overviews—even step-by-step guides—for creating architectural models and imagery, from the use of specific software packages to colored chalk, cardboard, and #2 lead. While Architectural Drawing and Architectural Modelmaking probably won’t teach you anything you don’t know already, it is nonetheless useful to have these around for flipping through, filled with visual ideas for how to approach a design project afresh.

23) Makeshift Metropolis: Ideas About Cities by Witold Rybczynski (Scribner).

23) Makeshift Metropolis: Ideas About Cities by Witold Rybczynski (Scribner).

24) Ten Walks/Two Talks by Jon Cotner and Andy Fitch (Ugly Duckling Presse).

25) Urban Underworlds: A Geography of Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture by Thomas Heise (Rutgers University Press).

26) Monsterpieces: Once Upon a Time… of the 2000s! by Aude-Line Duliere and Clara Wong (ORO Editions).

In what could pass as a kind of zoologically-themed children’s book or architectural fairy tale—here, a good thing—Monsterpieces reimagines iconic buildings all over the world as everything but what those buildings were intended to be. A tour of monsters, spaceports, biomass plants, anaerobic hospitals, robo-arachnoid recycling centers, mutant spatial transformation, and more.

Thomas Heise, meanwhile, takes us down into the cultural underworld of the 20th-century literary metropolis, including “degenerate sex” and highly politicized urban race relations; Jon Cotner and Andy Fitch have assembled a series of dialogues framed by specific walks through the city, suggesting that friendship itself is a useful technique for maximizing the emotional effects of urban space; and Witold Rybczynski signs off on an ambitious new book, one that “summarizes what I have learned about city planning and urban development,” as he describes it. “Is the city the result of design intentions, or of market forces, or a bit of both?” Rybczynski asks, in an armchair question typical of the Theory Lite in which he traffics. “These are the questions I explore in this book.”

27) Visual Planning and the Picturesque by Nikolaus Pevsner (Getty Publications).

27) Visual Planning and the Picturesque by Nikolaus Pevsner (Getty Publications).

28) Limited Language: Rewriting Design by Colin Davies and Monika Parrinder (Birkhäuser).

29) A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain by Owen Hatherley (Verso).

30) A Peripheral Moment: Experiments in Architectural Agency: Croatia 1990-2010 by Ivan Rupnik et al. (Actar).

31) Worldchanging 2.0 edited by Alex Steffen (Abrams).

From the architectural “ruins” of New Labour to the influence and role of the Picturesque in the history of British town planning, this cluster of five titles gives us architecture both as historical practice and as subject of critique. In Croatia, for instance, we read that “political instability and creative innovation” have worked with equal intensity to generate new, experimental building typologies, while Limited Language explores a variety of “hybrid media forms” through which design can or should be communicated.

Worldchanging 2.0 is more explicitly practical. This new, bright yellow edition is a thorough revision—even a total rewrite—of the first version, suggesting new directions for ecologically aware design practices, community collaborations, and the ground-up spatial improvement of 21st-century life.

32) BIG by Bjarke Ingels Group (Archilife).

32) BIG by Bjarke Ingels Group (Archilife).

33) Archipiélago de Arquitectura by Miguel Mesa et al. (Mesa Editores).

34) Hylozoic Ground: Liminal Responsive Architecture edited by Pernilla Ohrstedt and Hayley Isaacs (Riverside Architectural Press).

35) Modern Ruins: Portraits of Place in the Mid-Atlantic Region by Shaun O’Boyle (Penn State University Press).

Finally, I wanted to give a shout-out to four recent books I had the pleasure of directly contributing to. Those contributions run the gamut from a discussion of the spatial strategies of football (both FIFA and NFL) and what I describe as “live-action crystallography” in the work of Bjarke Ingels, to plate tectonics reconsidered as an extreme form of long-term landscape design in Archipiélago de Arquitectura (another beautifully designed publication by Mesa Editores).

In Shaun O’Boyle’s photographs of the “modern ruins” of the Mid-Atlantic, meanwhile, including his explorations of Eastern State Penitentiary (an abandoned prison located mere blocks from where BLDGBLOG was born in Philadelphia), I ruminate on the psychological effects of architectural survival, when a seemingly doomed building or architectural type manages to live on for covert exploration by a new generation. Incidentally, O’Boyle’s book has a funny backstory involving the website Metafilter. And, in a multiply-authored book published to coincide with last year’s Venice Biennale, I take a look at the “synthetic geology” of architect Philip Beesley and his installation Hylozoic Ground.

If you happen to stumble upon any of these four last books, I’d love to know what you think of the essays.

* * *

All

Books Received:

August 2015,

September 2013,

December 2012,

June 2012,

December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”),

May 2010,

May 2009, and

March 2009.

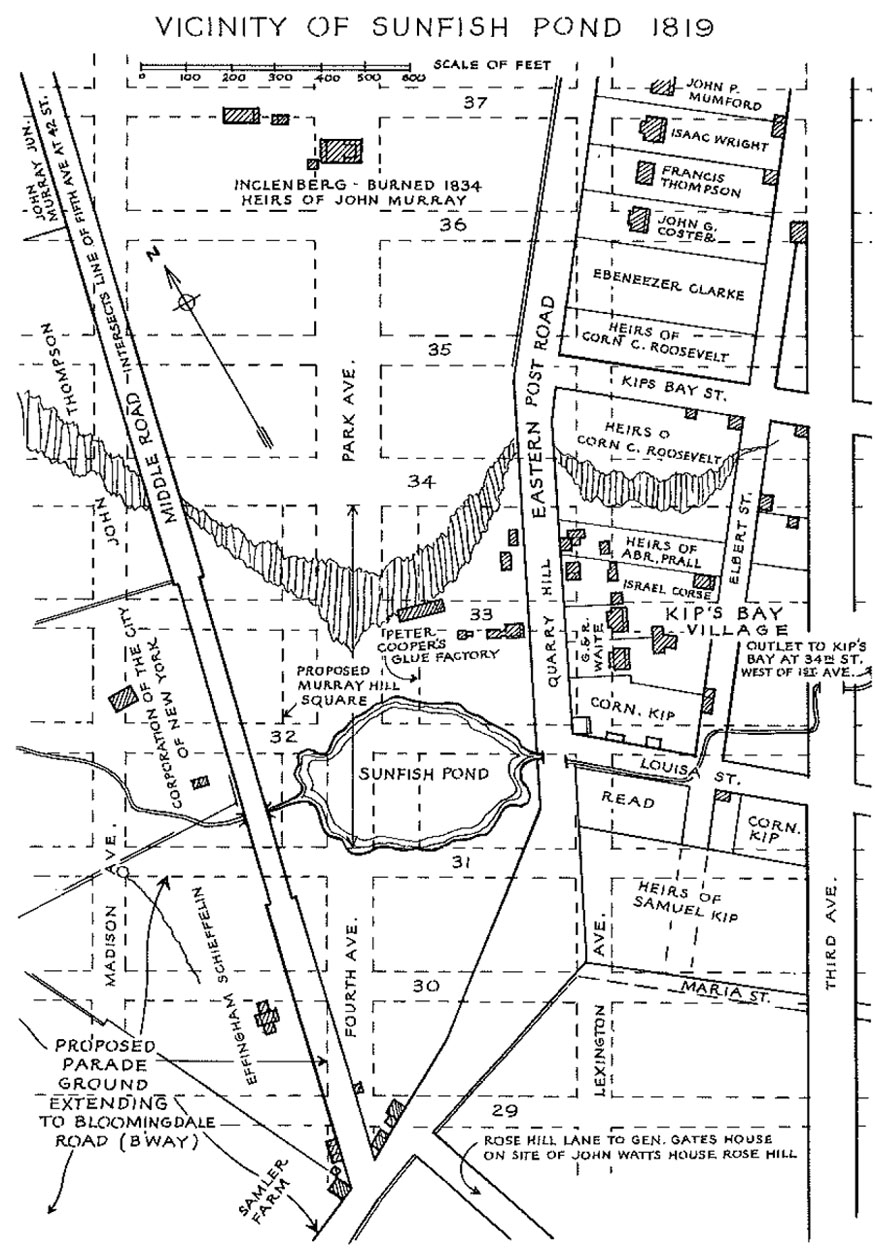

[Image: Sunfish Pond].

[Image: Sunfish Pond].

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Images: From the

[Images: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: The door to the underworld; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The door to the underworld; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Disguised infrastructure; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: A view through the front door of 58 Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A view through the front door of 58 Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Two views of the tunnel vent on Governors Island; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Two views of the tunnel vent on Governors Island; photos by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower; photo via

[Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower; photo via  [Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of  [Image: The house on Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The house on Joralemon Street; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by

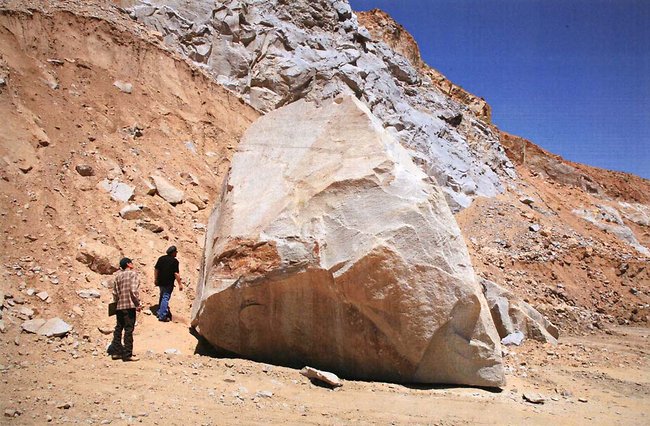

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The rock in question; photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

[Image: The rock in question; photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

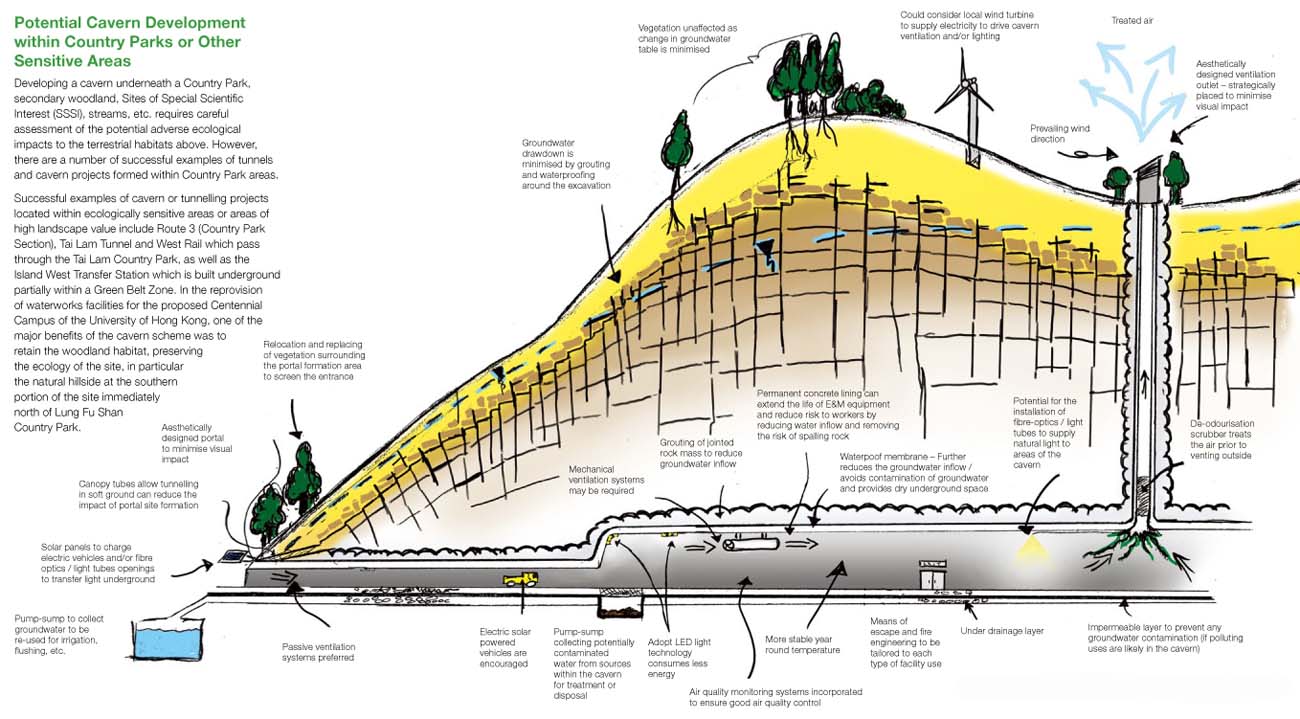

[Image: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Image: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Images: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Images: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Image: Photo by Brian Harkin for

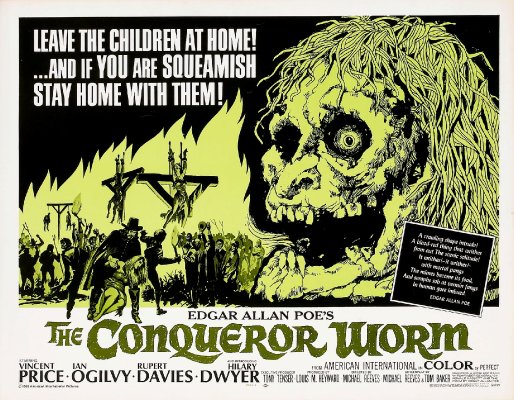

[Image: Photo by Brian Harkin for  [Image: Promotional poster for the otherwise unrelated film

[Image: Promotional poster for the otherwise unrelated film

Keep your eye out for a copy of the magazine, however, because the following text is accompanied by a fold-out world map, featuring many of the sites revealed by Wikileaks.

Keep your eye out for a copy of the magazine, however, because the following text is accompanied by a fold-out world map, featuring many of the sites revealed by Wikileaks.  [Image: A manganese mine in Gabon, courtesy of the

[Image: A manganese mine in Gabon, courtesy of the  [Image: The Robert-Bourassa generating station, part of the

[Image: The Robert-Bourassa generating station, part of the

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The “Electric Aurora,” from Specimens of Unnatural History, by

[Image: The “Electric Aurora,” from Specimens of Unnatural History, by  Finally, Nicola and I will fall out of the car in a state of semi-delirium in La Jolla, California, where I’ll be presenting at a 2-day symposium on

Finally, Nicola and I will fall out of the car in a state of semi-delirium in La Jolla, California, where I’ll be presenting at a 2-day symposium on

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Proposal for the Stockholm Public Library by

[Image: Proposal for the Stockholm Public Library by

4)

4)  7)

7)  10)

10)  13)

13)  16)

16)  20)

20)  23)

23)  27)

27)  32)

32)