The London-based architectural group ScanLAB—founded by Matthew Shaw and William Trossell—has been doing some fascinating work with laser scanners.

The London-based architectural group ScanLAB—founded by Matthew Shaw and William Trossell—has been doing some fascinating work with laser scanners.

Here are three of their recent projects.

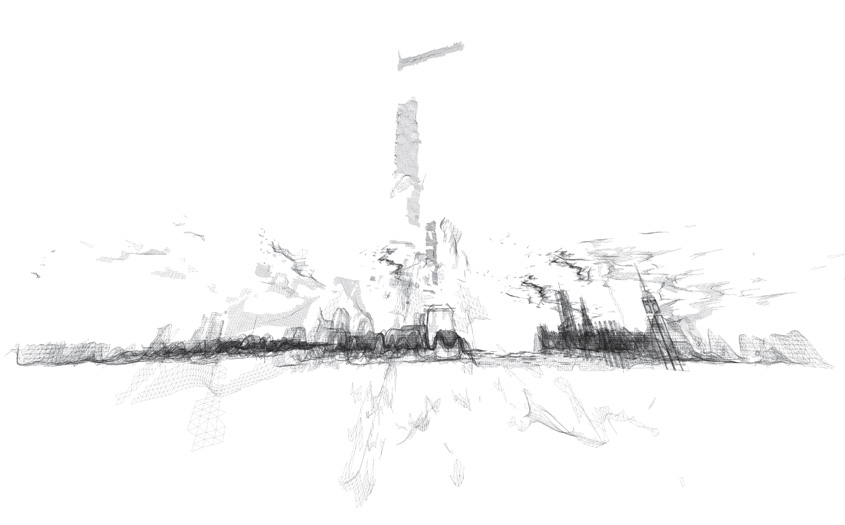

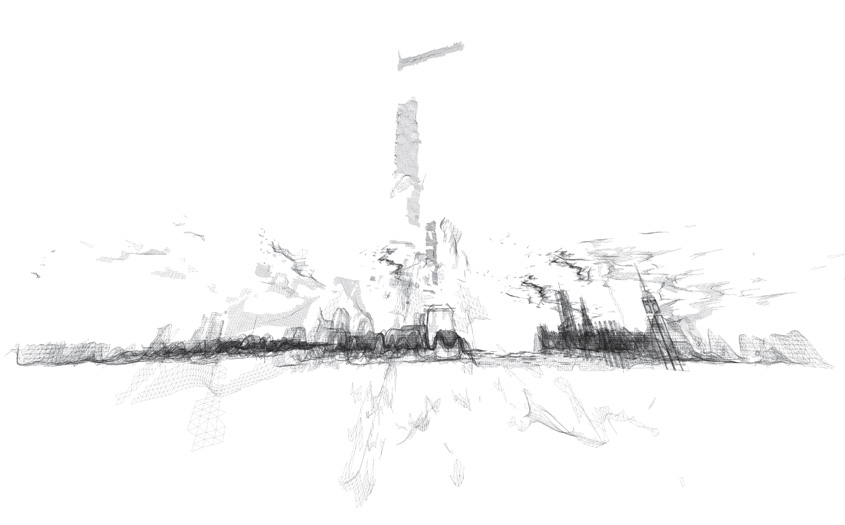

1) Scanning Mist. Shaw and Trossell “thought it might be interesting to see if the scanner could detect smoke and mist. It did and here are the remarkable results!”

[Images: From Scanning the Mist by ScanLAB].

[Images: From Scanning the Mist by ScanLAB].

In a way, I’m reminded of photographs by Alexey Titarenko.

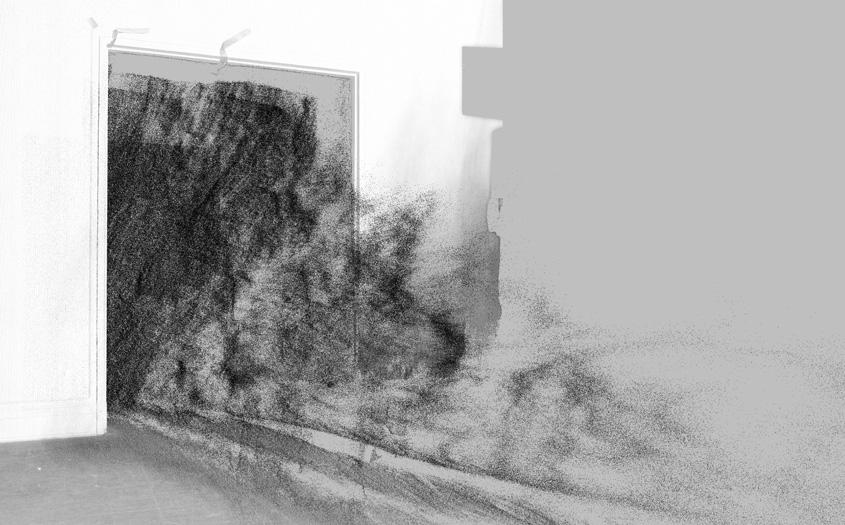

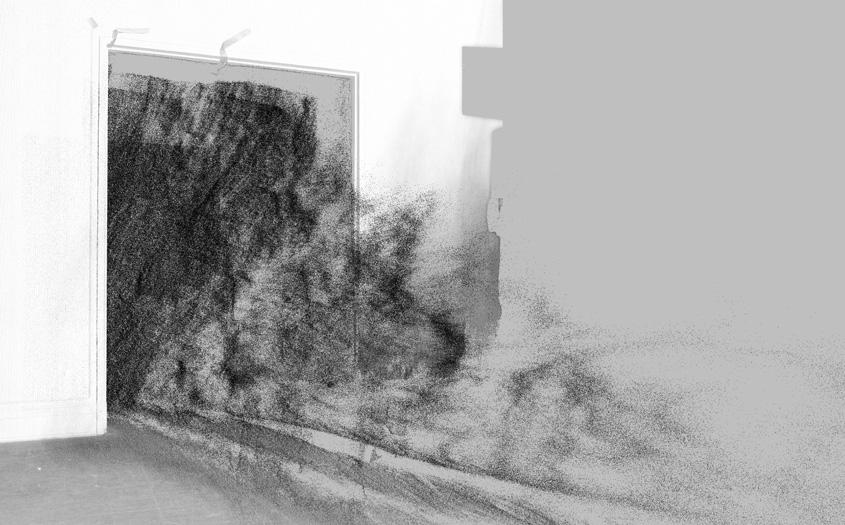

2) Scanning an Artificial Weather System. For this project, ScanLAB wanted to “draw attention to the magical properties of weather events.” They thus installed a network of what they call “pressure vessels linked to an array of humidity tanks” in the middle of England’s Kielder Forest.

[Image: From Slow Becoming Delightful by ScanLAB].

[Image: From Slow Becoming Delightful by ScanLAB].

These “humidity tanks” then, at certain atmospherically appropriate moments, dispersed a fine mist, deploying an artificial cloud or fog bank into the woods.

[Image: From Slow Becoming Delightful by ScanLAB].

[Image: From Slow Becoming Delightful by ScanLAB].

Then, of course, Shaw and Trossell laser-scanned it.

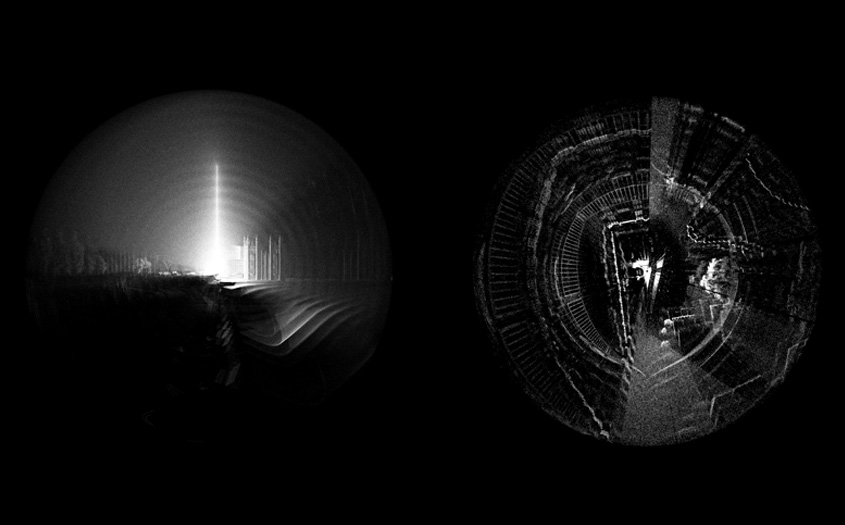

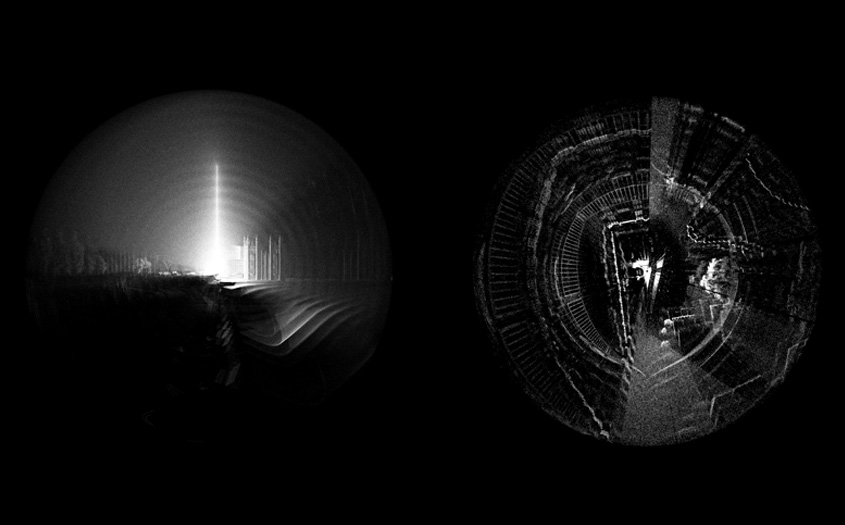

3) Subverting Urban-Scanning Projects through “Stealth Objects.” The architectural potential of this final project blows me away. Basically, Shaw and Trossell have been looking at “the subversion of city scale 3D scanning in London.” As they explain it, “the project uses hypothetical devices which are installed across the city and which edit the way the city is scanned and recorded.”

Tools include the “stealth drill” which dissolves scan data in the surrounding area, creating voids and new openings in the scanned urban landscape, and “boundary miscommunication devices” which offset, relocate and invent spatial data such as paths, boundaries, tunnels and walls.

The spatial and counter-spatial possibilities of this are extraordinary. Imagine whole new classes of architectural ornament (ornament as digital camouflage that scans in precise and strange ways), entirely new kinds of building facades (augmented reality meets LiDAR), and, of course, the creation of a kind of shadow-architecture, invisible to the naked eye, that only pops up on laser scanners at various points around the city.

[Images: From Subverting the LiDAR Landscape by ScanLAB].

[Images: From Subverting the LiDAR Landscape by ScanLAB].

ScanLAB refers to this as “the deployment of flash architecture”—flash streets, flash statues, flash doors, instancing gates—like something from a short story by China Miéville. The narrative and/or cinematic possibilities of these “stealth objects” are seemingly limitless, let alone their architectural or ornamental use.

Imagine stealth statuary dotting the streetscape, for instance, or other anomalous spatial entities that become an accepted part of the urban fabric. They exist only as representational effects on the technologies through which we view the landscape—but they eventually become landmarks, nonetheless.

For now, Shaw and Trossell explain that they are experimenting with “speculative LiDAR blooms, blockages, holes and drains. These are the result of strategically deployed devices which offset, copy, paste, erase and tangle LiDAR data around them.”

[Images: From Subverting the LiDAR Landscape by ScanLAB].

[Images: From Subverting the LiDAR Landscape by ScanLAB].

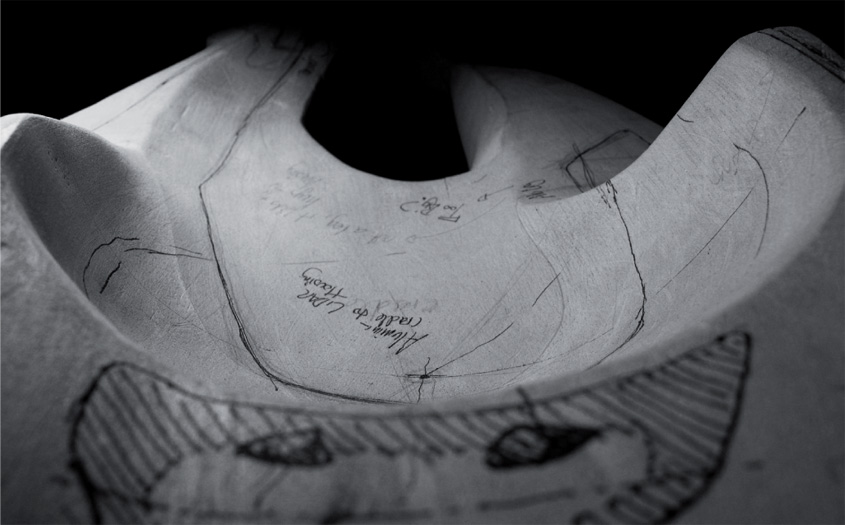

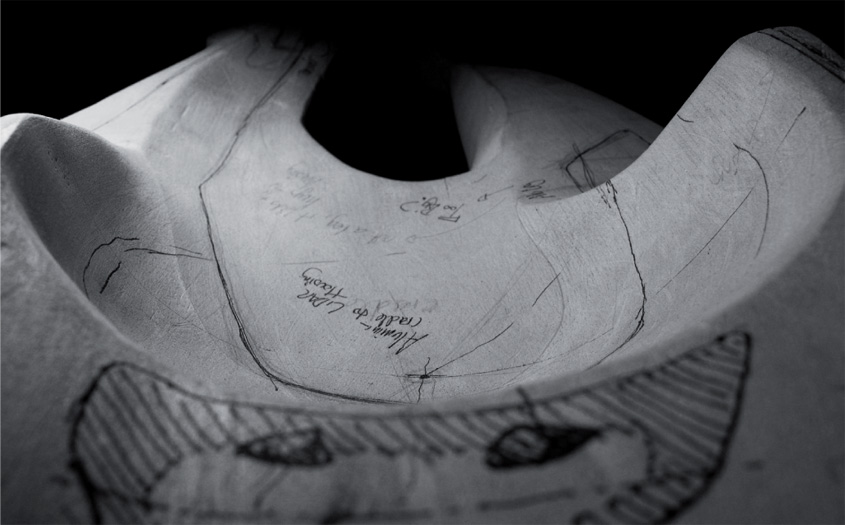

Here is one such “stealth object,” pictured below, designed to be “undetected” by laser-scanning equipment.

Of course, it is not hard to imagine the military being interested in this research, creating stealth body armor, stealth ground vehicles, even stealth forward-operating bases, all of which would be geometrically invisible to radar and/or scanning equipment.

In fact, one could easily imagine a kind of weapon with no moving parts, consisting entirely of radar- and LiDAR-jamming geometries; you would thus simply plant this thing, like some sort of medieval totem pole, in the streets of Mogadishu—or ring hundreds of them in a necklace around Washington D.C.—thus precluding enemy attempts to visualize your movements.

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].

Briefly, ScanLAB’s “stealth object” reminds me of an idea bandied about by the U.S. Department of Energy, suggesting that future nuclear-waste entombment sites should be liberally peppered with misleading “radar reflectors” buried in the surface of the earth.

The D.O.E.’s “trihedral” objects would produce “distinctive anomalous magnetic and radar-reflective signatures” for anyone using ground-scanning equipment above. In other words, they would create deliberate false clues, leading potential future excavators to think that they were digging in the wrong place. They would “subvert” the scanning process.

In any case, read more at ScanLAB’s website.

[Image: An airplane hangar in Utah, via the U.S.

[Image: An airplane hangar in Utah, via the U.S.  [Image: Interior view of same hangar, via U.S.

[Image: Interior view of same hangar, via U.S.  [Image: Utah airplane hangar, via U.S.

[Image: Utah airplane hangar, via U.S.  [Image: One of Google’ Loon balloons; screen grab from

[Image: One of Google’ Loon balloons; screen grab from

The London-based architectural group

The London-based architectural group  [Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB]. [Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the

[Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the  [Image: Photo by John Gay: an F/A-18 creates a condensation cone as it breaks the speed of sound].

[Image: Photo by John Gay: an F/A-18 creates a condensation cone as it breaks the speed of sound]. The city of Venice has begun to rebrand its tap water, calling it

The city of Venice has begun to rebrand its tap water, calling it  [Image: Marcel Duchamp,

[Image: Marcel Duchamp,  [Image: Photo by Jonathan Brown. Brown reviewed the launch on his blog,

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Brown. Brown reviewed the launch on his blog,  [Image: Antony Gormley’s Blind Light, 2007, courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/

[Image: Antony Gormley’s Blind Light, 2007, courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/ [Image:

[Image: