[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From Cabinet].

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From Cabinet].

Katabatic Winds

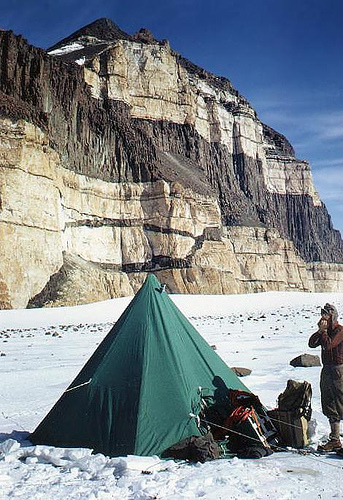

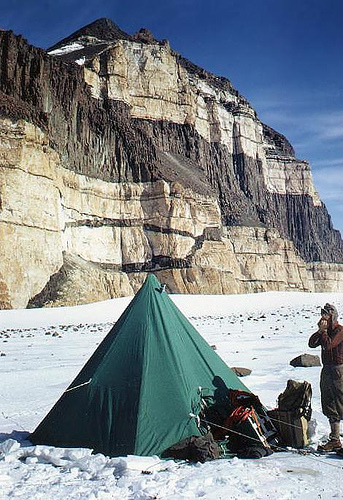

In the current issue of Cabinet Magazine, Jackie Dee Grom introduces us to ventifacts, or “geologic formations shaped by the forces of wind.”

Jackie was a member of the 2004 National Science Foundation’s Long-Term Ecological Research project in Antarctica, during which she took beautiful photographs of ventifactual geology – three of which were reproduced in Cabinet. (These are my own scans).

“The McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica,” she writes, “are home to one of the most extreme environments in the world – a polar desert blasted by ferocious winds, deprived of all but minimal rain, and beset by a mean annual temperature of negative twenty degrees Celsius.”

It is there, in the Antarctic Dry Valleys, that “gravity-driven winds pour off the high polar plateau, attaining speeds of up to two hundred kilometers per hour.”

In the grip of these aeolian forces, sand and small pebbles hurl through the air, smashing into the volcanic rocks that have fallen from the valley walls, slowly prying individual crystals from their hold, and sculpting natural masterworks over thousands of years. The multi-directional winds in this eerie and isolated wasteland create ventifacts of an exceptional nature, gouged with pits and decorated with flowing flutes and arching curves.

In his recent book Terra Antarctica: Looking into the Emptiest Continent, landscape theorist and travel writer of extreme natural environments William Fox describes similar such ventifacts as having been “completely hollowed out by the wind into fantastic eggshell-thin shapes.”

The “cavernous weathering” of multi-directional Antarctic winds – as fast as hurricanes, and filled with geologic debris – can “reduce a granite boulder the size of a couch into sand within 100,000 years.”

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From Cabinet].

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From Cabinet].

The B-flat Range

A part of me, however, can’t help but re-imagine these weird and violent geologies as sonic landmarks, or accidental musical instruments in the making. You hear them before you see them, as they scream with polar tempests.

A common theme on BLDGBLOG is the idea that natural landscapes could be transformed over time into monumental sound-generation machines. I’ve often thought it would be well worth the effort, for instance, if – in the same way that Rome has hundreds of free public fountains to fill the water bottles of thirsty tourists – London could introduce a series of audio listening posts: iPod-friendly masts anchored like totem poles throughout the city, in Trafalgar Square, Newington Green, the nave of St. Pancras Old Church, outside the Millennium Dome.

You show up with your headphones, plug them in – and the groaning, amplified, melancholic howl of church foundations and over-used roadways, the city’s subterranean soundtrack, reverbed twenty-four hours a day through contact mics into the headsets of greater London – greets you in tectonic surround-sound. London Orbital, soundtracking itself in automotive drones that last whole seasons at a time.

In any case, looking at photos of ventifacts I’m led to wonder if the entirety of Antarctica could slowly erode over millions of years into a musical instrument the size of a continent. The entire Transantarctic Range carved into flutes and oboes, frigid columns of air blasting like Biblical trumpets – earth tubas – into the sky. The B-flat Range. Somewhere between a Futurist noise-symphony and a Rube Goldberg device made of well-layered bedrock.

Where the design of musical instruments and landscape architecture collide.

[Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at Ross Sea Info].

[Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at Ross Sea Info].

Flocks of birds in Patagonia hear the valleys rumble, choked and vibrating with every inland storm, atonal chords blaring like fog horns for a thousand of miles. Valve Mountains. Global wind systems change, coiling through hundreds of miles of ventifactual canyons and coming out the other end, turned round upon themselves, playing that Antarctic instrument till it’s eroded beneath the sea.

In his ultimately disappointing but still wildly imaginative novella, At the Mountains of Madness, H.P. Lovecraft writes about a small Antarctic expeditionary team that stumbles upon an alien city deep in the continent’s most remote glacial valleys. It is a city “of no architecture known to man or to human imagination, with vast aggregations of night-black masonry embodying monstrous perversions of geometrical laws.” Its largest structures are “sometimes terraced or fluted, surmounted by tall cylindrical shafts here and there bulbously enlarged and often capped with tiers of thinnish scalloped disks.”

Even better, “[a]ll of these febrile structures seemed knit together by tubular bridges crossing from one to the other at various dizzy heights, and the implied scale of the whole was terrifying and oppressive in its sheer gigantism.”

More relevant to this post, of course, Lovecraft describes how the continent’s “barren” and “grotesque” landscape – as unearthly as it is inhuman – interacted with the polar wind:

Through the desolate summits swept ranging, intermittent gusts of the terrible antarctic wind; whose cadences sometimes held vague suggestions of a wild and half-sentient musical piping, with notes extending over a wide range, and which for some subconscious mnemonic reason seemed to me disquieting and even dimly terrible.

Perhaps his team of adventurers has just stumbled upon the first known peaks of the B-Flat Range…

[Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at Ross Sea Info].

[Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at Ross Sea Info].

[For something else also howling an eternal B-flat: “Astronomers in England have discovered a singing black hole in a distant cluster of galaxies. In the process of listening in, the team of astronomers not only heard the lowest sound waves from an object in the Universe ever detected by humans” – but they’ve discovered that it’s emitting, yes, B-flat].

[Image: A project by Haus-Rucker-Co].

[Image: A project by Haus-Rucker-Co]. [Image: An “inflatable nested toroid structure” patented by NASA (PDF)].

[Image: An “inflatable nested toroid structure” patented by NASA (PDF)]. [Image: Inflatable toroid test; via NASA/Wikipedia].

[Image: Inflatable toroid test; via NASA/Wikipedia]. [Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the

[Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at  [Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at