[Image: Caspar David Friedrich, “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (c. 1818).]

[Image: Caspar David Friedrich, “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (c. 1818).]

[NOTE: I have dozens of posts—from book reviews to news items—sitting in my drafts folder that I never published for some reason. In re-reading this, from summer 2019, I thought I’d publish it.]

The tone of a new piece by Matthew Walther in The Week hits just shy of satire, but it makes an interesting—and, I would suggest, valid—point about the Apollo moon landing as more of an art historical event, a direct extension of European Romanticism, than it was a scientific one.

“What Goethe began at Weimar in 1789 ended on August 15, 1969,” Walther writes. “Apollo 11 was the culmination of the Romantic cult of the sublime prefigured in the speculations of Burke and Kant, an artistic juxtaposition of man against a brutal environment upon which he could project his fears, his sympathies, his feelings of transcendence.” Note the use of the word man.

The primarily aesthetic nature of the first Apollo mission becomes clearer when one considers it from the perspective of both the participants and the spectators. The lunar landing was not a scientific announcement or a political press conference; it was a performance, a literal space opera, a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk that brought together the efforts of more than 400,000 people, performed before an audience of some 650 million.

I’m reminded of Kathleen Jamie’s critique of Robert Macfarlane’s work, published in the London Review of Books several years ago. There, Jamie mocked the current state of nature writing as a genre of the “lone enraptured male,” in her words, who she instead portrays as a figure of mythic delusion seeking self-aggrandizing solitude amongst inhuman things.

“What’s that coming over the hill?” Jamie asks. “A white, middle-class Englishman! A Lone Enraptured Male! From Cambridge! Here to boldly go, ‘discovering’, then quelling our harsh and lovely and sometimes difficult land with his civilised lyrical words.” Of course, to boldly go is clearly a sarcastic reference to a particular kind of explorer’s impulse “to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

In this context, consider Walther’s own comment that much of modern expeditionary literature—such as Antarctic diaries or the records of long ship journeys—was often written by “hard men” who “put their will in the service of a literary mania for feelings of remoteness, hugeness, and brooding oceanic emptiness. What a shame that we have been able to produce no great lunar literature to succeed the writings by Byron, the Shelleys, Tennyson, and Melville that both immortalized and inspired the great hypothermic pioneers.”

Men sending themselves to the moon, men climbing mountains, men staring down glacial landscapes alone or moving into mountain huts and man-caves.

I remember waking up from a dream once, maybe ten or twelve years ago*, in which I had been the author of a novel called Space. In that dream, my (purely imaginary) novel was about a man who abandons his family—leaving his wife and kids without notice—to find “space” for himself elsewhere, an ill-considered quest for solitude that was emotionally and financially devastating for the people he left behind, but a feeling of “space” he valued so much that he could not bring himself to worry about the pain it might cause to others. In other words, it was space refigured as a kind of masculine cruelty, a weapon for solitude-seeking men who can afford to walk away—space as freedom from consequences masquerading as self-sufficiency. (I wrote a description of the dream down the next morning and thus still remember it.)

In any case, I will say—perhaps because I am blinded by my own demography—that the idea of expeditionary solitude as a kind of landscape project, something that can lure hikers into remote national forests or pull unaccompanied astronauts into deep valleys on the dark sides of distant worlds, needn’t necessarily be gendered and needn’t necessarily have any scientific value at all. Humans alone in an experience of awe, surrounded by geology, can have nothing more than aesthetic value—of course, whether it’s $152 billion worth of aesthetic value is another question entirely.

*UPDATE: Looking back at my notes, I actually had this dream in September 2014.

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

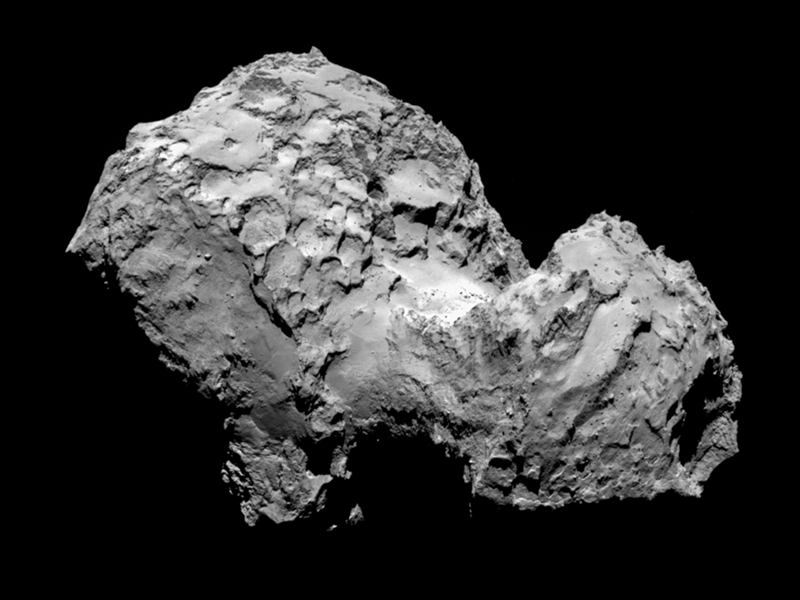

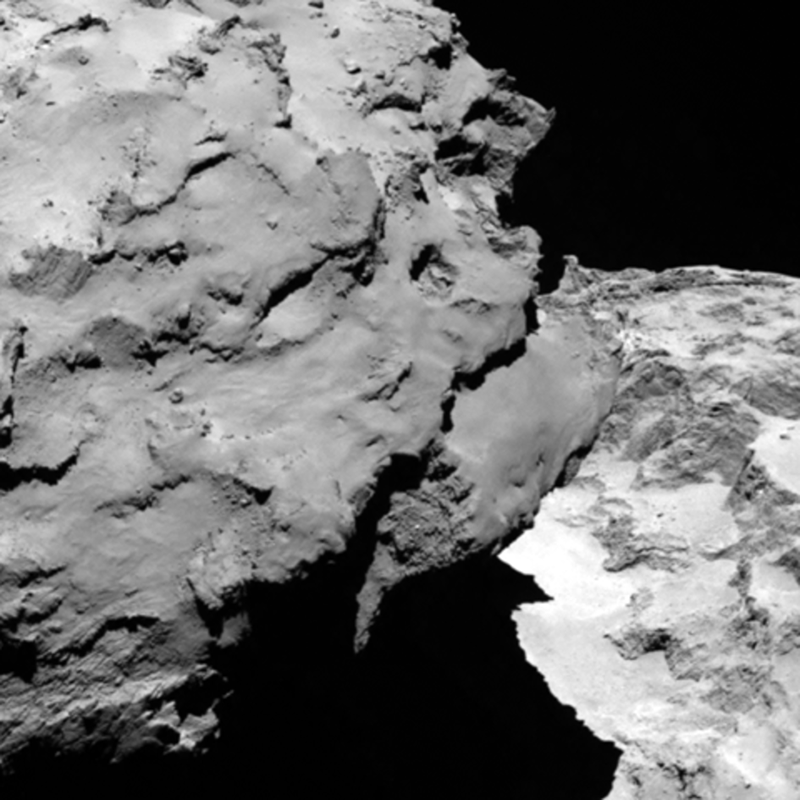

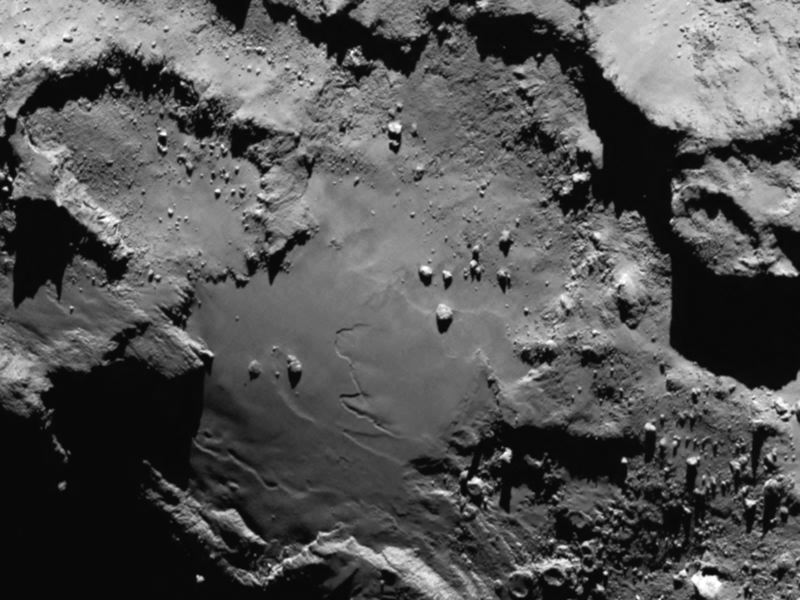

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the

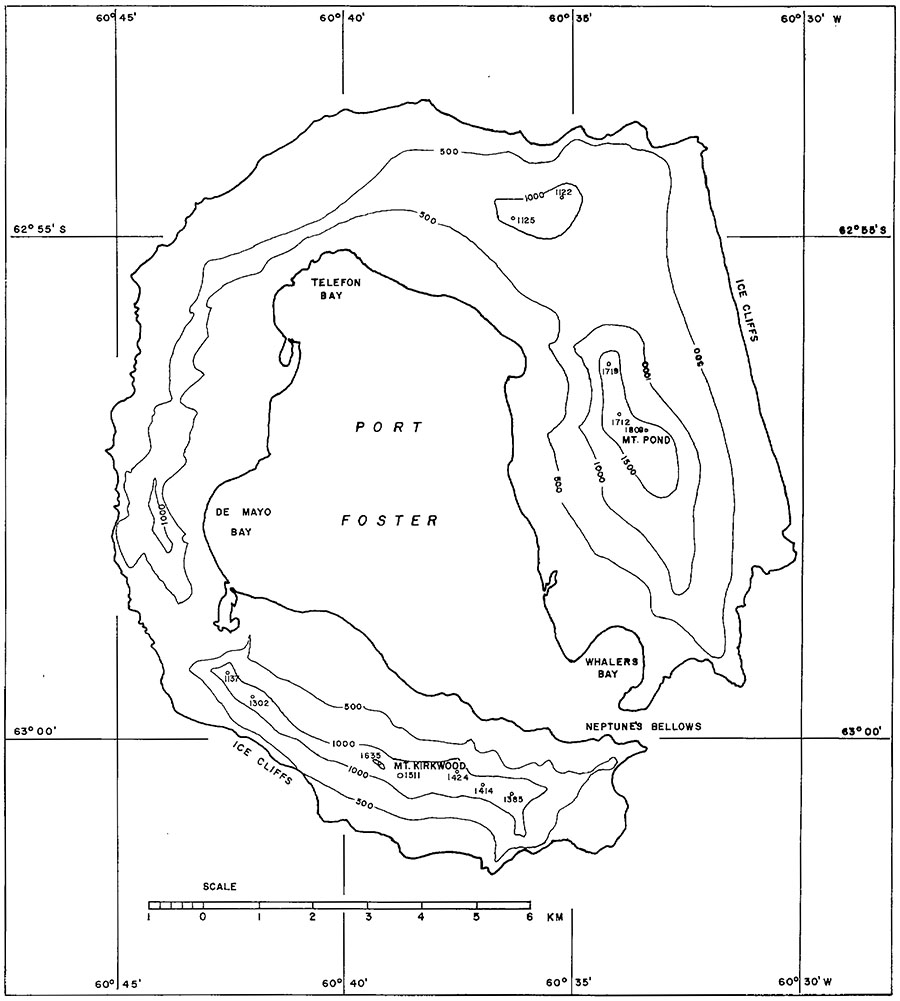

[Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna].

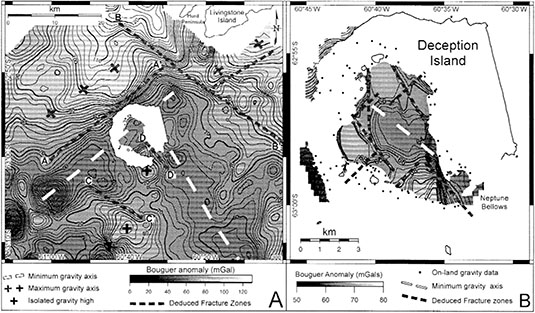

[Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna]. [Image: A map of Deception Island, taken from an otherwise unrelated paper called “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” published in Antarctic Science (2005)].

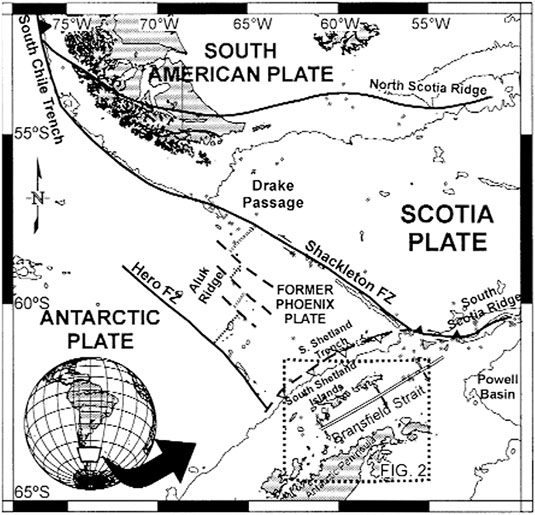

[Image: A map of Deception Island, taken from an otherwise unrelated paper called “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” published in Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

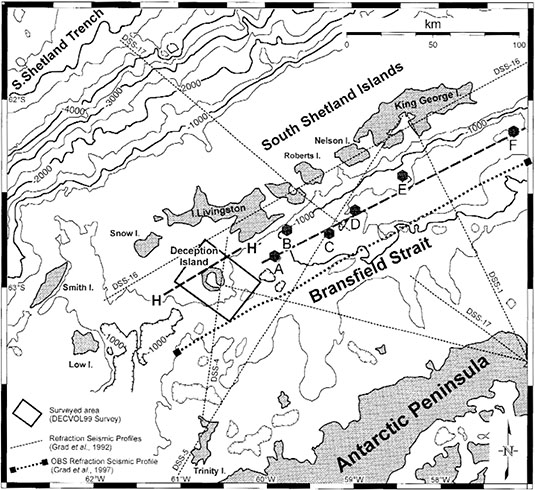

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

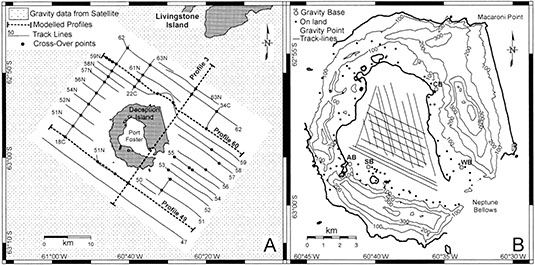

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: The

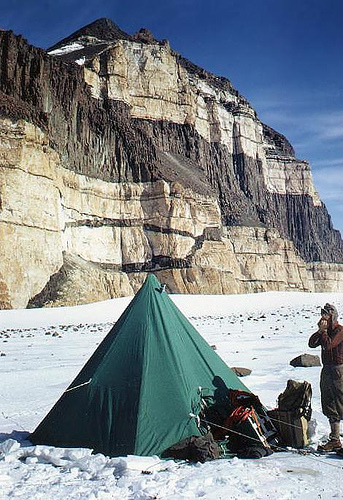

[Image: The  [Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via

[Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via  [Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via

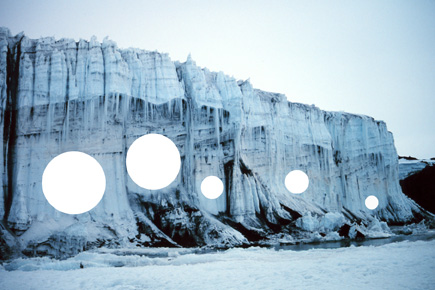

[Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via  [Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from

[Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at  [Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at