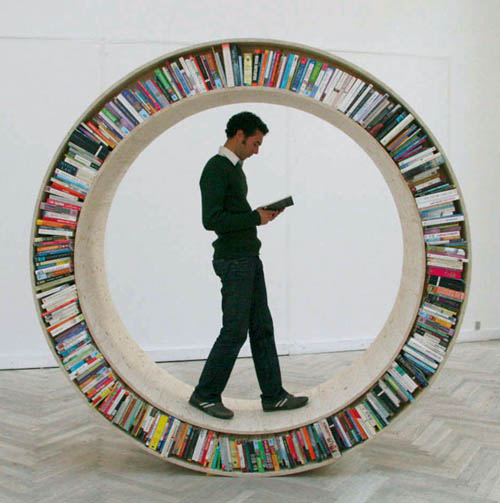

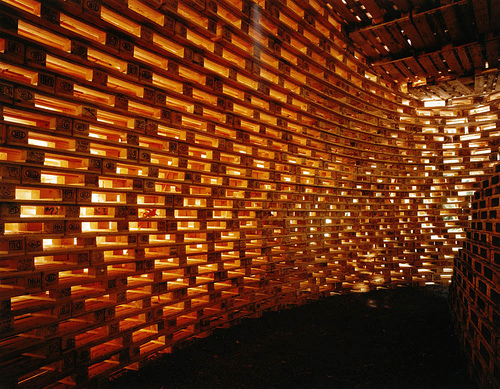

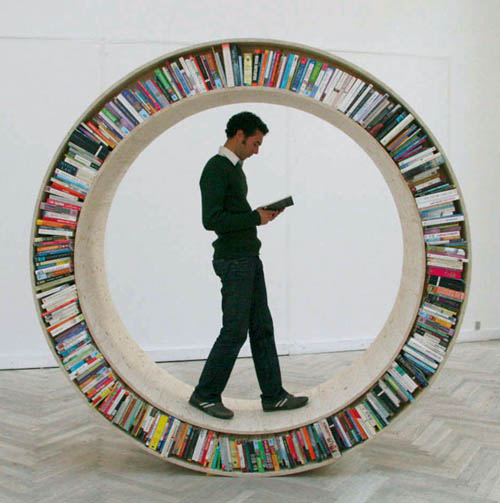

[Image: “Archive II” from the Archive Series by David Garcia Architect, Copenhagen].

[Image: “Archive II” from the Archive Series by David Garcia Architect, Copenhagen].

When I started the “Books Received” series last year, I did so just in time to box all my books up, put them in storage for what was supposed to be a three-month trip—and then abandon the series with only two posts written. But now it’s May 2010, that “three-month” trip has still not ended (the one-year mark is in two weeks), my things are still out in an L.A. storage warehouse gathering dust, and I’ve managed to hoard a whole new collection of books and papers.

About to hit the road once again now, for a trip within the trip, heading north to spend the summer in Montreal, I thought I’d revive the “Books Received” posts with a look at some of the many, many pieces of reading material that have gathered in our apartment over the past half-year. As before, I have not read all of the following books, which means I cannot vouch for all of their quality (except in a few cases that I will note); also, as before, these are not all new books. They are newly purchased—or newly received as review copies—but they are not necessarily hot off the press.

And with that…

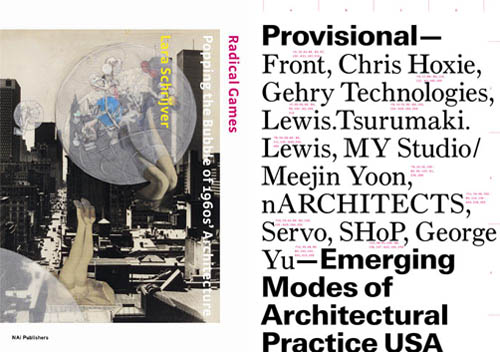

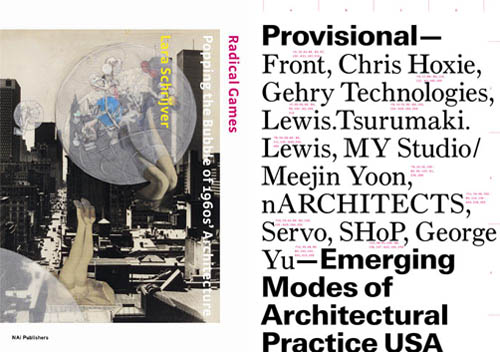

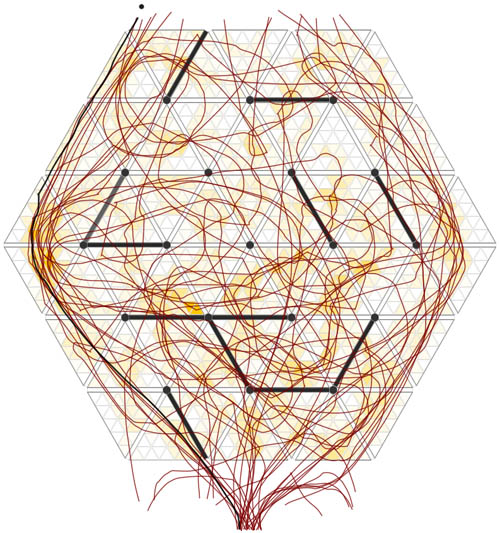

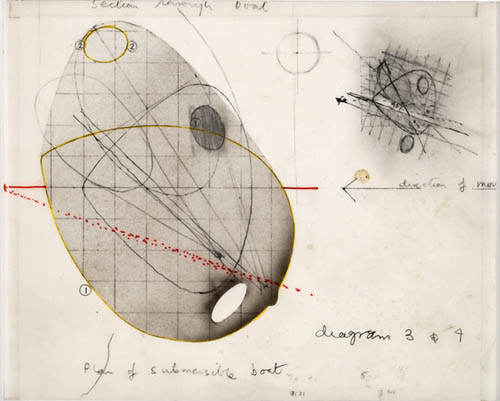

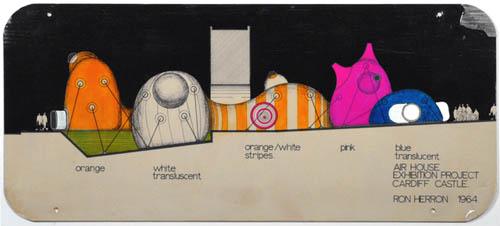

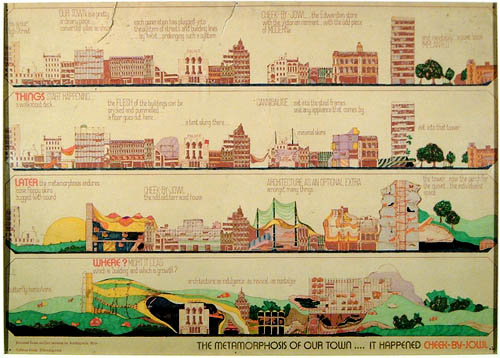

—Radical Games by Lara Schrijver (Netherlands Architecture Institute). Schrijver looks back at the “radical movements” of the 1960s, to “a moment in the history of architecture when revolutionary ideals were paramount and dreams became drawings.” Her goal, however, is to uncover how the ideals of three specific groups—Archigram, the Situationists, and Venturi & Scott Brown—maintained a confusing dependency on the very Modernist philosophies they were trying to dispute. This continues to have effects today, Schrijver argues, in muddying the waters of both theoretical debate and experimental practice.

—Radical Games by Lara Schrijver (Netherlands Architecture Institute). Schrijver looks back at the “radical movements” of the 1960s, to “a moment in the history of architecture when revolutionary ideals were paramount and dreams became drawings.” Her goal, however, is to uncover how the ideals of three specific groups—Archigram, the Situationists, and Venturi & Scott Brown—maintained a confusing dependency on the very Modernist philosophies they were trying to dispute. This continues to have effects today, Schrijver argues, in muddying the waters of both theoretical debate and experimental practice.

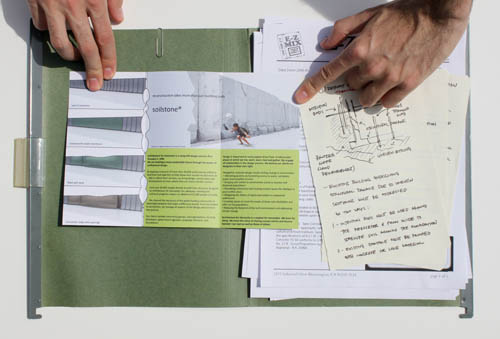

—Provisional: Emerging Modes of Architectural Practice USA, edited by Elite Kedan, Jon Dreyfous, and Craig Mutter (Princeton Architectural Press). Speaking of architectural practice, this fantastically designed (by Project Projects) book shows how architects actually work and how their buildings come together, including nARCHITECTS’ extraordinary “Wind Shape.” A very useful and interesting look at the organizational innovations, technical breakthroughs, and work-flow challenges that architectural offices now face. In fact, if there are forthcoming titles, designed to the same fabulous standard, called Emerging Modes of Architectural Practice Europe, …Asia, …Africa, …South America, and so on, I would snap all of them up.

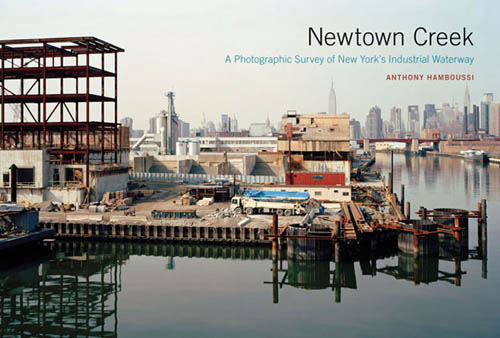

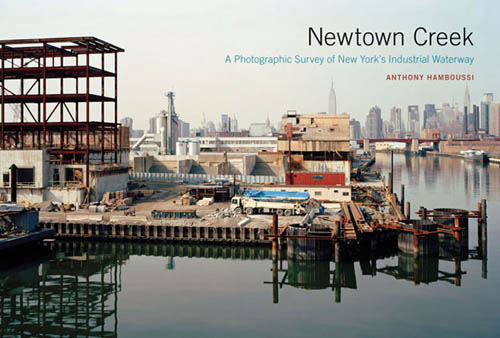

—Newtown Creek: A Photographic Survey of New York’s Industrial Waterway by Anthony Hamboussi (Princeton Architectural Press). From gargantuan salt piles to paving yards, UPS loading docks to derelict oil terminals and the sludge tanks of the NY Department of Sanitation, Hamboussi leads a photogeographic tour through the industrial landscapes of Newtown Creek, dividing Brooklyn and Queens. “Having worked along the creek for about a decade,” Paul Parkhill writes in the book’s afterword, on the other hand, “I can say with some conviction that any assumptions about abandonment are misplaced. Behind the street walls and cyclone fencing, inside the shuttered factories and warehouses, there exists a world hidden to the casual observer. Newtown Creeks reflects, in the words of one waterfront planning official, the ‘backyard’ of New York City. Desolate in spots, disgusting in others, it is far from abandoned.”

—Newtown Creek: A Photographic Survey of New York’s Industrial Waterway by Anthony Hamboussi (Princeton Architectural Press). From gargantuan salt piles to paving yards, UPS loading docks to derelict oil terminals and the sludge tanks of the NY Department of Sanitation, Hamboussi leads a photogeographic tour through the industrial landscapes of Newtown Creek, dividing Brooklyn and Queens. “Having worked along the creek for about a decade,” Paul Parkhill writes in the book’s afterword, on the other hand, “I can say with some conviction that any assumptions about abandonment are misplaced. Behind the street walls and cyclone fencing, inside the shuttered factories and warehouses, there exists a world hidden to the casual observer. Newtown Creeks reflects, in the words of one waterfront planning official, the ‘backyard’ of New York City. Desolate in spots, disgusting in others, it is far from abandoned.”

— Meet The Nelsons by Wes Jones and Pendulum Plane by the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design). These two pamphlets from the LA Forum unfortunately suffer from bad production, with almost instantly cracking spines and pages falling loose within minutes of reading. No matter, the Oyler Wu pamphlet in particular has some fantastic details, including beautiful shots of their Lebbeus Woods-like sketchbooks and some backstage glimpses of the “Live Wire” installation they did for SCI-Arc.

— Meet The Nelsons by Wes Jones and Pendulum Plane by the Oyler Wu Collaborative (Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design). These two pamphlets from the LA Forum unfortunately suffer from bad production, with almost instantly cracking spines and pages falling loose within minutes of reading. No matter, the Oyler Wu pamphlet in particular has some fantastic details, including beautiful shots of their Lebbeus Woods-like sketchbooks and some backstage glimpses of the “Live Wire” installation they did for SCI-Arc.

—The Future History of the Arctic by Charles Emmerson (PublicAffairs). Emmerson takes us through the now-rapidly shifting geography north of the Arctic Circle, where nation-state territorial ambitions and private-sector mineral & gas claims—not to mention thawing international shipping lanes, package tourism, and global climate change—are beginning to collide.

—The Future History of the Arctic by Charles Emmerson (PublicAffairs). Emmerson takes us through the now-rapidly shifting geography north of the Arctic Circle, where nation-state territorial ambitions and private-sector mineral & gas claims—not to mention thawing international shipping lanes, package tourism, and global climate change—are beginning to collide.

—The Edge of Physics: A Journey to Earth’s Extremes to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe by Anil Ananthaswamy (HMH). I’m halfway through this, and absolutely loving it. There are sensitive, remote, large-scale, and theoretically complex physics experiments going on all over the world, complete with massive pieces of infrastructure that such things require. So why not take a trip around the world and visit these extraordinary sites, as well as the unearthly landscapes in which they sit? Ananthaswamy does exactly that, taking us into an abandoned mine in Minnesota, to a neutrino detector deep beneath Russia’s Lake Baikal, up into the mountain deserts of South America, and past hulking telescopes in dark regions all over the world. All travel writing should be this interesting.

—Dust: The Inside Story of its Role in the September 11th Aftermath by Paul Lioy (Rowman & Littlefield). In the book’s Prologue, Lioy writes that, “Within twenty-four hours of the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center (WTC) in New York City, representatives from several governmental agencies asked me about the dust that was released during the collapse of each tower.”

The thick gray and fluffy dust seemed to be everywhere, settling on all of the animate and inanimate objects in its path. It covered the skin and clothes of many of those who had survived but who had been trapped in harm’s way. You could see it being resuspended in the air after official vehicles drove through Manhattan. What was in that dust and its companion plume of smoke that was moving across Brooklyn and out to sea? At that time, I didn’t know the answer to this question.

Lioy—a “specialist in exposure science”—has thus written this investigative chemical analysis of the cloud: what was in it, its basic morphology, how it interacted with human tissue, and how long its residue actually stuck around in New York City.

—Poets in a Landscape by Gilbert Highet (New York Review of Books). This brand new, NYRB edition revives Highet’s classic textual history of Roman poets, zooming in through the curtain of their words to focus on the background landscapes within which their poetic events took place—revealing a geography of lost place-names, gardens, villages, city fringes, and farms. An earlier edition of Highet’s book was praised in an old post on the excellent blog Some landscapes.

—Poets in a Landscape by Gilbert Highet (New York Review of Books). This brand new, NYRB edition revives Highet’s classic textual history of Roman poets, zooming in through the curtain of their words to focus on the background landscapes within which their poetic events took place—revealing a geography of lost place-names, gardens, villages, city fringes, and farms. An earlier edition of Highet’s book was praised in an old post on the excellent blog Some landscapes.

—Traveling Heroes: In the Epic Age of Homer by Robin Lane Fox (Vintage). This book has been greeted with mixed reviews, but the premise still thrills me: Fox has written a survey of “traveling heroes”: “particular Greeks at a particular phase in the ancient world who travelled with mythical stories of gods and heroes in their minds.” Or this, from the back cover description: Fox “explores how the intrepid Mediterranean seafarers of eight-century B.C. Greece encountered strange new sights—volcanic mountains, vaporous springs, huge prehistoric bones—and weaved them into the myths of gods, monsters, and heroes that would become the cornerstone of Western civilization.”

—The Routes of Man: How Roads Are Changing the World and the Way We Live Today by Ted Conover (Knopf). The premise of this book is fantastically simple: to travel the world’s roads, to ask how they have shaped human culture, and to reveal their literal resurfacing of the planet. After all, “Roads constitute the largest human-made artifact on earth,” Conover writes, so why not approach them as an anthropologist might? The execution so far, however, has left me underwhelmed. At the moment, Conover has just spent an awfully long time writing in a faux-naive voice about the South American jungle, telling us far less about roads, in any real sense, than about his own travels through this remote, intensely rural region that he can’t seem adequately to decipher. I’m finding myself wishing that Matthew Coolidge of the Center for Land Use Interpretation had written this book—or that a similarly themed book comes out soon, perhaps by the authors of mammoth—but I hope this sense of anticlimax dissipates as I continue reading.

—The Road to Ubar: Finding the Atlantis of the Sands by Nicholas Clapp (Mariner). I picked this up after seeing a brief reference to it in Michael Welland’s excellent book Sand. At first, it sounds like total b.s.—a lost city called the “Atlantis of the Sands,” known only through rumors and myth, like something published by Weiser. But it turns out to be true: there is a lost trading city beneath the sand dunes of Oman, and the whole thing disappeared when it collapsed into a sinkhole. Read this old New York Times review if you’re not convinced; there, we read that Clapp

assembled a group of collaborators that included a remote-imaging geologist from J.P.L.; an Arabic-speaking expedition wrangler with a knighthood; a fund-raiser; a cameraman (the personal quest having meanwhile become a film project); a sound man; Clapp’s wife, Kay; and Juris Zarins, an archeologist with a special interest in the Arabian incense trade. In 1990, Sultan Qaboos ibn Said granted them access not just to a remote zone of desert but also to one of his helicopters. After some reconnaissance flights, a more laborious search in Land Rovers led the team to a fruitful dig site in the Omani desert—though at an unexpected location, under an unexpected name. Over the next four years, Zarins, with a crew of helpers, would excavate that site tellingly.

To reveal here just what they found, and where they found it, would betray the suspense of Clapp’s narrative.

Think of it as Indiana Jones meets subterranean desert hydrology.

—The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times by Adrienne Mayor. (Princeton University Press). What an amazing topic for a book: how did ancient cultures understand, collect, and eventually explain fossils from gigantic creatures that they had no scientific means of understanding? From myths of dragons to fossilized deities, what cultural reactions did these petrified remains inspire? Looking back at the fossil-hunting record of Mediterranean cultures 2000 years ago, Mayor attempts to answer those questions. On another note, Mayor’s most recent book, The Poison King, also looks great.

—Obelisk: A History by Brian A. Curran, Anthony Grafton, Pamela O. Long, and Benjamin Weiss (MIT). An illustrated, multiply-authored account of how massive stone plinths were quarried, transported, publicly erected, and culturally adored from Ancient Egypt to Paris in the 21st century.

—Obelisk: A History by Brian A. Curran, Anthony Grafton, Pamela O. Long, and Benjamin Weiss (MIT). An illustrated, multiply-authored account of how massive stone plinths were quarried, transported, publicly erected, and culturally adored from Ancient Egypt to Paris in the 21st century.

—TV Towers by Friedrich von Borries, Matthias Böttger, and Florian Heilmeyer. This “architectural history of TV towers” tracks the political history and structural forms of television-broadcasting towers all over the world, primarily in Europe—yet, as the authors point out, “the most recent are being erected in up-and-coming Asian cities and in the Middle East.”

TV towers have been—and still are—the most visible symbols of an otherwise invisible technological revolution. The geographical spread of such towers traces twentieth century political history until this day: rivalry between political systems in East and West was followed by competition among global cities for touristic and economic appeal… TV towers are the cathedrals of a media society.

The book was published to coincide with an exhibition at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum that closed in March 2010.

—Other Space Odysseys, edited by Mirko Zardini and Giovanna Borasi (Canadian Centre for Architecture/Lars Müller). I’m looking forward to seeing this exhibition in person up in Montreal next month. This pamphlet-sized accompanying booklet does a great job in portraying the loopy design history of architects who have directly engaged with the space program (and, specifically, with human experience on the moon). The Alessandro Poli chapter is a highlight.

—Al Manakh 2 (Volume/Archis). A sober, recessionary note, kicked off right away by Rem Koolhaas’s introductory letter, haunts this sequel to Al-Manakh. Koolhaas sounds more like a defiant sports fan who knows his favorite team is having an off-season (but who has decided to cheer them on, nonetheless). “Dubai is an experiment that will never be repeated,” he writes; it is (was?) “an entirely different construct, the brainchild of a local minority that generously invited manpower and expertise from everywhere to assemble an artificial community, to test, explore and put into practice the relationship between Islam and modernity.” Whether or not this massive—and, physically, very nicely realized—book amplifies or eviscerates the “understandable Schadenfreude” Koolhaas mentions in his intro is something I will have to find out while reading it this summer.

—Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It by Richard Clarke and Robert Knake (Ecco). This is another book I’m roughly halfway through (and enjoying, precisely because of its alarming nature). If Clarke and Knake are to be believed—and they seem like reliable narrators—the U.S. is wildly underprepared for any sort of concentrated, militarized cyber-attack, whether from another nation-state or from an organized network of criminal hackers. “The U.S. military is no more capable of operating without the Internet than Amazon.com would be,” the authors write, and the eye-popping infrastructural vulnerabilities that they point out here and there—such as counterfeit routers, manufactured in China and sold throughout the U.S. market, with security flaws suspiciously (and deliberately?) well-placed for later attacks, or the “logic bombs” that have been found “all over our [the U.S.’s] electric grid”—are worth the price of the book alone.

—Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It by Richard Clarke and Robert Knake (Ecco). This is another book I’m roughly halfway through (and enjoying, precisely because of its alarming nature). If Clarke and Knake are to be believed—and they seem like reliable narrators—the U.S. is wildly underprepared for any sort of concentrated, militarized cyber-attack, whether from another nation-state or from an organized network of criminal hackers. “The U.S. military is no more capable of operating without the Internet than Amazon.com would be,” the authors write, and the eye-popping infrastructural vulnerabilities that they point out here and there—such as counterfeit routers, manufactured in China and sold throughout the U.S. market, with security flaws suspiciously (and deliberately?) well-placed for later attacks, or the “logic bombs” that have been found “all over our [the U.S.’s] electric grid”—are worth the price of the book alone.

—Constructing a New Agenda for Architecture: 1993 to the Present, edited by A. Krista Sykes (Princeton Architectural Press). This is an historically valuable collection of essays commonly assigned by architecture professors over the past seventeen years—but, to be honest, if you want interesting ideas for future design projects, I think you’re better off reading even just a handful of the other titles mentioned above. This is not universally true for everyone reading this blog, of course, and I don’t mean to be idiotically dismissive of the past decade and a half of theoretical writing; after all, Sykes has put together an impressive survey. But, for my own needs, impulsive architectural speculation is a much more valuable, projective form of theorizing than the overly careful, citational micropolitics that too often passed for academic work in the 1990s.

—Finally, The Other City by Michal Ajvaz (Dalkey Archive). Ajvaz’s novel is a “strange and lovely hymn to Prague,” we read, falling somewhere between magic realism, Labyrinths, and perhaps Jeff VanderMeer. “Can there really exist a world in such close proximity to our own,” Ajvaz asks, “one that seethes with such strange life, one that was possibly here before our own city and yet we know absolutely nothing about it?” That is “indeed quite possible,” his narrator concludes, wandering through streets always on the verge of mutating into something else.

* * *

All

Books Received:

August 2015,

September 2013,

December 2012,

June 2012,

December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”),

May 2010,

May 2009, and

March 2009.

[Image: Fabric urbanism: a “tent city,” via Bracket].

[Image: Fabric urbanism: a “tent city,” via Bracket]. [Image: A “containerized” field hospital by the Red Cross and UN].

[Image: A “containerized” field hospital by the Red Cross and UN]. [Image: Deployable Incident Command Post (ICP) by Reeves].

[Image: Deployable Incident Command Post (ICP) by Reeves].

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Images: The

[Images: The

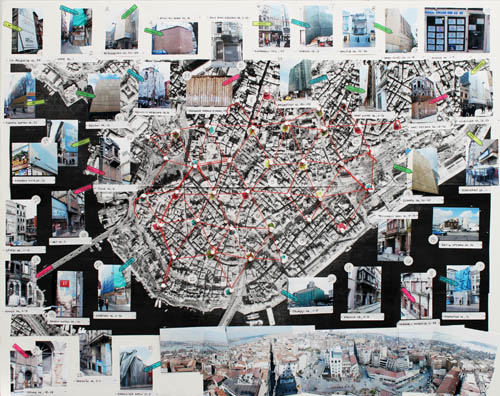

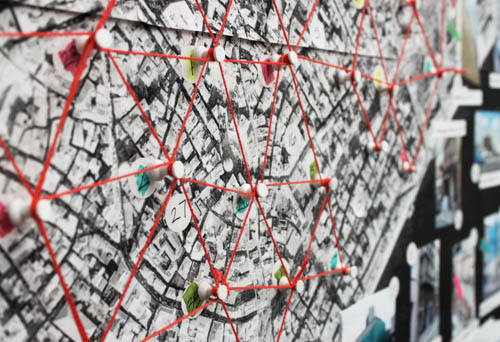

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

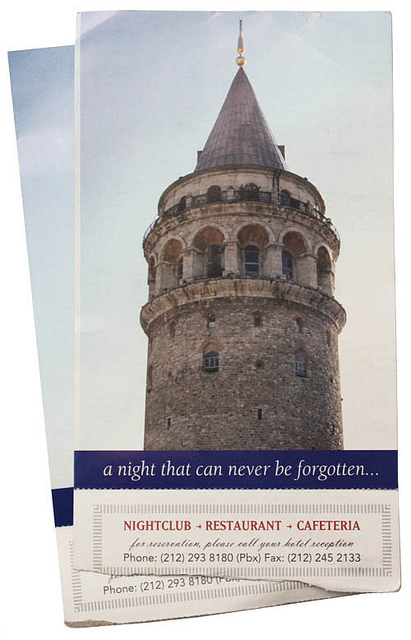

[Image:  [Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to

[Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to

[Images:

[Images:

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: The “steel giant” near Chernobyl; all photos via

[Images: The “steel giant” near Chernobyl; all photos via  [Image: The “brain scorcher,” via

[Image: The “brain scorcher,” via  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: STALKER game images from this very extensive

[Images: STALKER game images from this very extensive  [Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].  [Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Images: Spreads from “

[Images: Spreads from “ [Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from  [Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “

[Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “ [Image: “Archive II” from the

[Image: “Archive II” from the  —

— —

— —

—  —

— —

— —

— —

— [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Images: Movement-typologies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Movement-typologies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth,” or psycho-cybernetic human navigational testing ground, constructed near Euston Station].

[Image: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth,” or psycho-cybernetic human navigational testing ground, constructed near Euston Station].

[Images: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth”].

[Images: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth”]. [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Maze-studies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Maze-studies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal

[Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal  [Image: “Proposal for a

[Image: “Proposal for a  [Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a

[Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a  [Image: Proposal “

[Image: Proposal “ [Image: Stephen Graham’s

[Image: Stephen Graham’s  [Images:

[Images:

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].