[Image: A1 (1930) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: A1 (1930) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

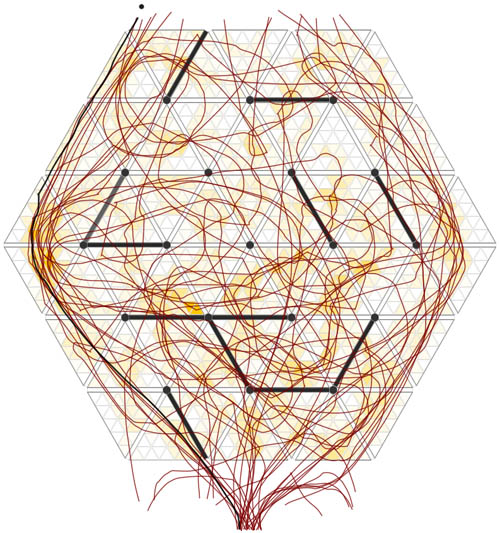

I meant to write about these way back when they first appeared in the Paris Review, but alas. In any case, Wacław Szpakowski was a trained architect who dedicated an inordinate amount of his own free time to hand-drawing elaborate mazes and patterns using only a single line.

[Image: B9 (1926) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: B9 (1926) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

“When he was eighty-five,” Sarah Cowan writes in a review of a show mounted by the Miguel Abreu Gallery in New York City, “Wacław Szpakowski wrote a treatise for a lifetime project that no one had known about. Titled ‘Rhythmical Lines,’ it describes a series of labyrinthine geometrical abstractions, each one produced from a single continuous line. He’d begun these drawings around 1900, when he was just seventeen—what started as sketches he then formalized, compiled, and made ever more intricate over the course of his life.”

[Image: F3 (1925) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: F3 (1925) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

Szpakowski’s notebooks are, according to Cowan, “a twentieth-century version of Leonardo da Vinci’s, with enthusiastic scribblings next to observations of architecture and diagrams of natural phenomena, from ocean currents to fir-tree needles.”

[Image: C4 (1924) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: C4 (1924) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

It’s hard to exaggerate how interesting these are from an architectural point of view: labyrinths of a single line, suggesting possibilities for infinite complexity along single paths of circulation. Room after room after room, laid out along a sufficiently complex corridor, becomes a building as large as a city.

[Image: F13 (1926) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: F13 (1926) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

I’m reminded of a recent project by Andrew Kudless of Matsys called “The Walled City (10-Mile Version),” which also featured a single megastructure made from one continuous 10-mile wall.

[Image: “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/Matsys].

[Image: “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/Matsys].

But the appeal of Szpakowski’s work would appear to extend well beyond the architectural. At times they resemble textiles, weaving diagrams, computer circuity, and even Arts & Crafts ornamentation, like 19th-century wallpapers designed for an era of retro-computational aesthetics.

[Images: (top to bottom) D4 (1925), D5 (1926), and D7 (1928) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Images: (top to bottom) D4 (1925), D5 (1926), and D7 (1928) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

Woodworking templates, patent drawings for fluidic calculators, elaborate game boards—the list of associations goes on and on.

[Image: B10 (ca. 1930) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: B10 (ca. 1930) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

For more, check out the write-up in the Paris Review,”>Paris Review and be sure to click through the various images over at the Miguel Abreu Gallery.

[Image: F1 (1925-1926) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

[Image: F1 (1925-1926) by Wacław Szpakowski, via Miguel Abreu Gallery].

(Originally spotted via Paul Prudence. Also of interest: The Switching Labyrinth.)

[Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Images: Movement-typologies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Movement-typologies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth,” or psycho-cybernetic human navigational testing ground, constructed near Euston Station].

[Image: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth,” or psycho-cybernetic human navigational testing ground, constructed near Euston Station].

[Images: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth”].

[Images: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth”]. [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Maze-studies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Maze-studies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].