[Image: Jeffrey Inaba].

[Image: Jeffrey Inaba].

Jeffrey Inaba teaches architectural theory and design studios at Columbia (where he is the founding director of C-Lab) and SCI-Arc (where he and Paul Nakazawa run SCIFI, the Southern California Institute for Future Initiatives); he heads Inaba Projects; and he regularly contributes to a wide variety of publications, not the least of which is Great Leap Forward: The Harvard Design School Project on the City.

BLDGBLOG spoke to Inaba about… well, about as many topics as we could fit into one phone conversation: Archigram, sports cars, golf courses, feng shui, Donald Trump, Saddam Hussein, penthouse design and the rise of Tribeca, hedge fund managers, spatial surplus, sustainable development in China, the economics of suburbia and global megaslums, dog training as a political metaphor, science fiction novels as a form of architectural research – etc. etc.

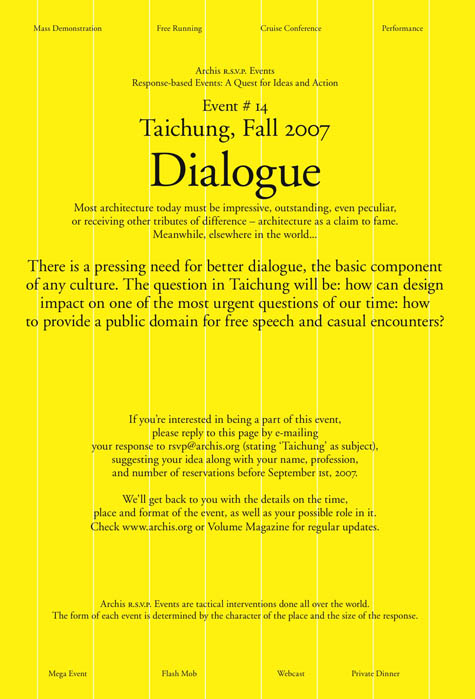

BLDGBLOG: With Volume 10 you call for more “agitation” in architectural discourse. Could you go into this a bit more? For instance, do we need a new Archigram or another Superstudio? Where will this agitation come from?

Jeffrey Inaba: It’d be great if there was another Archigram or Superstudio. [laughs] I certainly wouldn’t be against it. I think the reason for producing an entire issue on agitation was specifically a response to consensus culture. There’s a collective feeling within the US that it is important to agree on things, to find points that can be discussed or shared, and that differences should be smoothed over by elevating the discussion in a way that diminishes an opposition on another level. That seems to be triggered by an underlying sense that you’re either with us or you’re against us.

What seems ridiculous about that – not even on a content level, but on a deeper, structural level – is that these alliances and antagonisms are based on the least substantial of terms. So if only by two people agreeing with each other on a review, as critics, that somehow this would be the basis for an alliance seems ridiculous – just as not agreeing on a topic could trigger a war between two perceived points of view or ideologies.

Furthermore, when alliances are developed in tenuous terms like this, it doesn’t necessarily generate more in-depth discussion. You might have somebody who, for lack of a better example, is interested in technology, and they might form bonds with somebody who does, say, 17th century history – but strange bedfellows like this aren’t generating a more interesting discussion. There’s more of a symbolic alliance, rather than one that’s actually productive.

In that sense, it seems important to reintroduce the term agitation because its meaning has been diminished: it now means trouble-maker or rabble-rouser, or somebody who is disruptive for ill-founded reasons. But agitation can be a term that’s much broader: it can be an action that’s earnest, circumspect, interrogative, or subtle – as well as over the top. Our point would be to find means of agitating that aren’t just based upon the appeal of the rhetoric, or the loudness of the preaching. In that sense, we hope to expand the term agitation.

Once you re-introduce it, as well, you can begin to look out for it. That, for example, is how we came to do the piece on Pininfarina. I remember a hair stylist saying once that hair cutting would be so easy if it weren’t for ears. Similarly, designing super-sleek cars would be easy if it weren’t for the engine and the wheels – protrusions or obstructions that are essential to the object at hand and fundamental to what a car is. Hence the grill, the engine block, wheel well – all the things that produce bumps, or aesthetic agitations rather than streamlined forms. When looked at in this way, an entirely new vocabulary can be appreciated with Pininfarina.

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

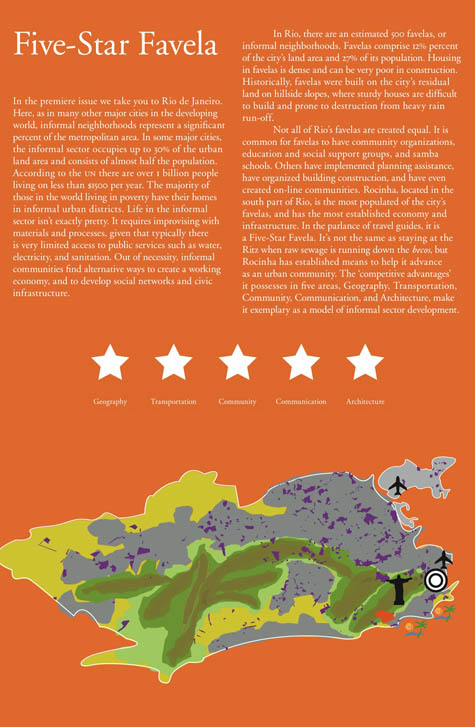

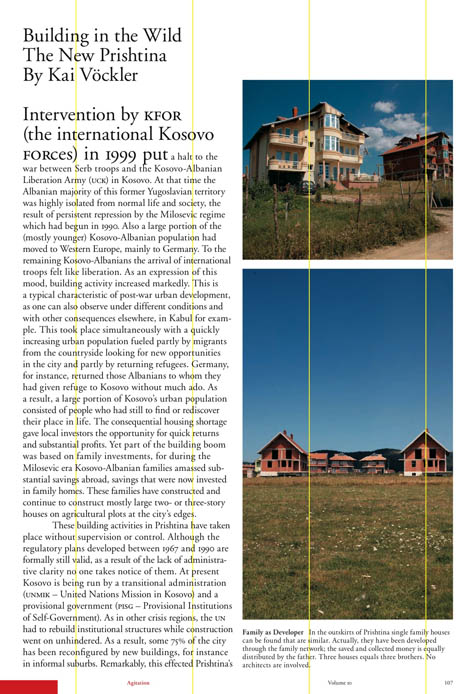

BLDGBLOG: And part of this agitation is your interest in the favela – the slum? In Volume 10 you published a whole travel guide to favelas, called Alibi.

Inaba: Yeah. And it’s definitely not meant in an ironic way. The idea with Alibi was that you could produce urban research in the form of a travel guide, so that it could be readable for people other than architects. It was produced to raise architectural and urban issues – like dealing with water run-off, plumbing, garbage, and property boundaries – and to present that in a format digestible to others.

In that sense, the genre of a travel guide is intentionally meant as a way to convey architectural information.

[Image: The cover page of Alibi, from Volume 10. For more on favelas, meanwhile, don’t miss BLDGBLOG’s earlier, two-part interview with Mike Davis].

[Image: The cover page of Alibi, from Volume 10. For more on favelas, meanwhile, don’t miss BLDGBLOG’s earlier, two-part interview with Mike Davis].

BLDGBLOG: But why favelas, in particular?

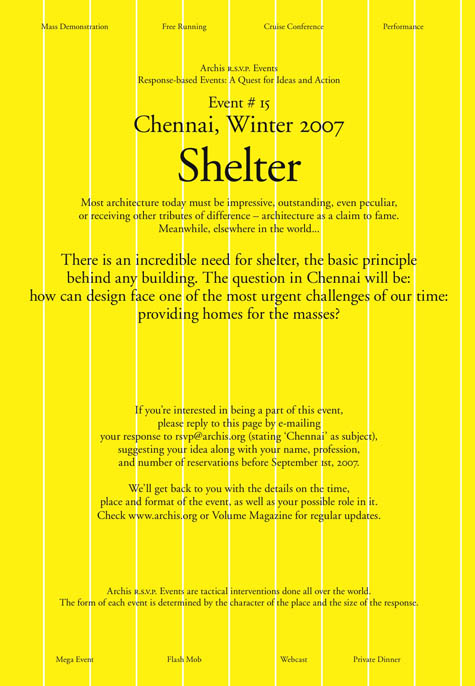

Inaba: You know, some of my other work has been on suburbia, and the thing that we’re more and more convinced by is that the 21st century megacity will be a space – or urban condition – not defined by 20th century concepts of density or urbanity. Instead, it will be determined by two things: the suburb and the favela – the informal. You can think of LA as a proto-condition for this.

But the places experiencing new architectural forms, new types of rapid growth, alternative patterns of collective development, extreme forms of communication, and a concern for planning stemming from necessity – these are all now happening in areas that are suburban, in areas that are informal. And that includes favelas.

These are the generative elements of the 21st century city.

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

BLDGBLOG: Favelas are architecturally interesting – but they’re economically generated. In other words, the architecture – the space – comes second. So where does the favela actually come from? Is a favela formed from the bottom-up, as an organic outgrowth of local conditions? Or is it formed from the top-down – as a kind of architectural symptom of globalization and economic inequality?

Inaba: That’s a really good question. You can find conditions in LA that you might think would be more typical of Mexico City, Cairo, or Lagos – and, yeah, I think you can read that through global capital flows, in the sense that now you have informal communities and suburbs next to one another, covering more area of the world than earlier forms of the city – like Manhattan, London, or Paris.

I’m not so interested in whether it’s top-down or bottom-up – or bottom-down, for that matter – but in acknowledging that there is more of it in the world now than there are 20th century downtowns.

BLDGBLOG: So these informal spaces and cities are sort of self-organizing? They generate more of themselves? They’re both productive and fractal?

Inaba: I don’t see favelas as being self-organizing, or that favelas should be celebrated for their spatial innovation – not at all. Nor do I think of the favela only as a victim of flows of capital investment.

What is interesting is that despite the potential of great amounts of capital to eradicate, favela urbanism is indestructible. It can exist right next to a central, concentrated corporate development. The only other thing that I can think of like that is the suburb.

The two have persistence – an ability to absorb growth and destruction. That used to be what was thought of as unique to the 20th century city. This alone merits why the suburb and favelas needs to be addressed in architecture schools.

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

BLDGBLOG: Perhaps you should train architecture students in suburban development! At the very least, that would shine a more architecturally interesting and creative light on all those cul-de-sacs.

Inaba: Another way to put it is that architectural form – what students learn and practice, what architectural programs produce – is focused on one marketplace: the marketplace of building design, not the marketplace of urban development. If the city is more complex and harder to understand at this given moment, because of globalization and environmental pressures, then – now more than ever – architects should be trying to explain it. I’m not sure that the technological investigation of form is the best use of our energy right now.

Now should be the very moment when we try to describe what the city is. It seems that advances in architectural form, as an expression of the contemporary moment, doesn’t in itself help to explain or understand these things.

BLDGBLOG: Changing tack a bit, in Great Leap Forward, much is made of feng shui, golf courses, and the idea of “politics, geography, and spirituality.” Could you tell me a bit more about your interest in this? I’m particularly drawn to the idea of “bad” feng shui – China’s building boom takes on a whole new meaning in this context.

Inaba: Today, in China, environmentalism – meaning eco-friendly cities – is the expression of “politics, geography, and spirituality.” Branding a development as environmentally friendly is both a marketing tool and a political enabler for even greater development.

Urban development in the name of environmentalism, and in the name of eco-friendly urbanism, could very well become the pretext for doing certain types of development that don’t actually reduce the rate of resource consumption: they set up conditions for even more rapid consumption, in the name of being politically, geographically, and spiritually sensitive.

Sustainable development is becoming an unquestioned process, embraced as a positive form of urbanism. It’s being over-used. In that way, it’s producing landscapes of bad feng shui.

BLDGBLOG: So, to some extent, feng shui really just means environmentally friendly?

Inaba: [laughs] Totally.

BLDGBLOG: Sustainability also lends a kind of critical immunity to new building projects – if something’s sustainable, no one wants to critique it. Being carbon neutral is like being handed an aesthetic Get Out of Jail Free card.

Inaba: That’s exactly it – it’s irreproachable as a moral position. For example, Shenzhen has been criticized for being bad urbanism, based on the grounds of taste; it’s said to be ill-planned, quickly developed, and with poorly designed buildings. Meanwhile, other cities are deemed to be better examples of urbanism because of their environmental sensitivity – having a low carbon footprint – but, as such, they’re exempt from other criteria of judgment.

One of the main features of eco-friendly design is its predisposition for suburb-like developments. In order to get large cities to accommodate large populations, in an environmentally sensitive way, why is it that all the projects result in a default language of green space and detached, single-family dwellings?

One of the ways that suburbia is emerging in the megacity is through the rhetoric of ecology: an urbanism of eco-friendly villas. It’s like Laguna Niguel. [laughs] Only it’s happening in China.

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 6].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 6].

BLDGBLOG: C-Lab has also produced some great work around the idea of excess space, or a kind of spatial surplus. For instance, you interviewed Robert A.M. Stern in Volume 6, and he points out that the quintessential sign of Manhattan luxury living – the penthouse – is actually just an unintended result of extra building space. The penthouse is a creative reuse of leftovers, so to speak. Could you talk about this a bit?

Inaba: There was an article in New York magazine by Jay McInerney about Tribeca now being the most expensive area in New York City – and, for that reason alone, there are people on the Upper East Side who want to move there.

BLDGBLOG: [laughter]

Inaba: His point is that it’s not because of the quality of Tribeca’s architecture, or because of the kinds of spaces you can buy there, or because of the urban experience. If design is said to add value, then it seems to add only fractional value: concentrated high real estate value adds value.

One of the things that’s also clear is that Tribeca now has the most penthouses.

What we wanted to show is that there is a new distribution in the luxury residential building type that responds to the demand for excessive space. If the penthouse used to be the top floor – one floor more exclusive than the other floors – then buildings now have multiple floors of penthouses: they are mostly “penthouses.” The piece shows that some buildings have more “penthouses” than non-penthouses.

Besides just chronicling this excess, we wanted to talk about our inaccessibility as a profession to this level of the city. There is a whole urban experience that we, as architects, don’t have access to. We don’t move in the same spaces, or social circles, or economic spheres. I, myself, don’t know anyone who manages a hedge fund; I don’t know, let alone dine with anyone in the private equity banking business who became super-super-mega-wealthy after Sarbanes-Oxley; I don’t have any access to that.

BLDGBLOG: How does one engage with that, though? Do you organize a house tour, or a photo essay, or some kind of conference between hedge fund managers and their architects, or…?

Inaba: It’s not an issue of gaining entry to this layer of New York for the benefit of architectural commissions, but to understand the economy and spaces of this New York, to be able to grasp what urbanism is today.

Architects can’t be involved in urbanism if we can’t experience it.

Just to reiterate the point: the city is going through a transformation where the most powerful economic stratum is not palpable on the street. In New York, during the banking boom of the late-80s and the tech boom of the 90s, feverish consumption and extreme wealth were evident. But this current period of even greater accumulation is hardly visible. Goldman Sachs gave out $19 billion in bonuses last year – but we don’t see the presence of that wealth in the general urban experience of New York.

So the general issue is less a matter of shaking hands with private equity guys, but figuring out how to respond to our professional dislocation from the city.

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 6].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 6].

BLDGBLOG: In some ways, that reminds me of your interview with Kanan Makiya, also from Volume 6, about Baathist architecture. Saddam’s palaces, in a funny way, look like something Donald Trump might build – a kind of baroque desert penthouse. Is there a dictatorial vernacular emerging in architecture today?

Inaba: Actually, Benedict Clouette did that interview – it’s really good. When we were looking at the material later, we were both struck by how humanistic those buildings made Saddam look! [laughs] Meaning that the architecture of state power and the architecture of first world residences don’t seem that far apart. Saddam’s palaces, while they’re really supposed to be about state power, look not so different from houses in New Jersey. And the scale now of residential buildings isn’t so different from the scale of buildings that were once meant to symbolize state power, on an institutional scale.

The dictatorial vernacular is not so far off from the American suburban vernacular.

[Image: Two pages from Volume 6].

[Image: Two pages from Volume 6].

BLDGBLOG: So the palace of the dictator is a kind of McMansion in the desert?

Inaba: Yeah – the scales are the same. It’s a vernacular that could as easily be used in Arizona as by a Baathist regime.

BLDGBLOG: Finally, how did you end up interviewing Cesar Millan, the “dog whisperer,” for Volume 10?

Inaba: It’s one of my favorite pieces that we’ve ever done. To some degree, it’s about the relationship between an animal sense and a human sense of the world, and Cesar’s ability to formulate that into a viable political message. He seems to be a person who would be an interesting politician for the US today, because he is overtly advocating domination – the way one animal dominates another within a pack. And, in fact, he wants to run for office.

His point is that, today, the UK and the US are run by weak leaders, leaders who are unstable, who don’t have enough discipline, and who don’t produce stability. By soliciting fear, they produce instability. So the way to respond to that is to create a clear form of dominance. For Cesar, assertiveness and physicality – the way a pack leader dominates a pack – is the type of logic that he wants to extend into politics. And he’s serious about it. If his initial popular appeal is that his methods are about this type of training exercised on your dog, I think the appeal of his show – which goes beyond dog owners – is that it affirms assertiveness in humans. It’s about the individual’s ability to be assertive.

I think it’s noteworthy to publish him because he wants to extend this onto a political level. For him, domination, physical assertiveness, discipline – these are all forms of a higher level of affection.

[Image: A page from Volume 10].

[Image: A page from Volume 10].

BLDGBLOG: The cruel father.

Inaba: In that sense, it’s not related to the urban, or to architecture; but we thought it was a really good articulation of a strategy of power – and so it was relevant to Volume magazine.

BLDGBLOG: Actually, one more question: I’m curious what you think about using other genres for architectural research. It seems that everyone today just writes long, footnoted articles for the same handful of academic journals – then they complain about lack of audience. But why don’t they write science fiction novels, or comic books, or even screenplays? Or a blog, for that matter? Do you think that these other, less traditional genres have any value for the future of architectural research?

Inaba: Absolutely. I think the point of issue 10 is that, for all the investment in architectural aesthetics at the moment, it seems like the terms that we use to discuss or define those aesthetics are surprisingly limited. We only have a few words to describe architectural form. By thinking through different genres – and their terms – we could expand our aesthetic vocabulary.

So you could operate on the level of a science fiction novel – but you could just as well embrace the travel guide, or the interview, or the photo-collage. These things, by their very diversity, have the ability to generate a range of aesthetics. We want to operate in other guises. When you look at a place through the lens of a travel guide, there are things about architecture that can be deciphered and explained with greater ease.

I think what’s important is our ability to extract things from the genre of science fiction, not to reproduce the look and feel of science fiction as a genre.

As architects, we can go beyond aesthetics – in the sense of beautiful buildings, or interesting buildings, or new buildings – and find public consequences both for architecture and architectural discussion.

Thanks to Jeffrey Inaba, for the conversation and for inviting me to critique some student projects at SCI-Arc this week, and to Benedict Clouette for setting all these interviews up in the first place.

[Image: Ole Bouman, photographed by Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk].

[Image: Ole Bouman, photographed by Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk]. BLDGBLOG: In

BLDGBLOG: In  BLDGBLOG: Again in

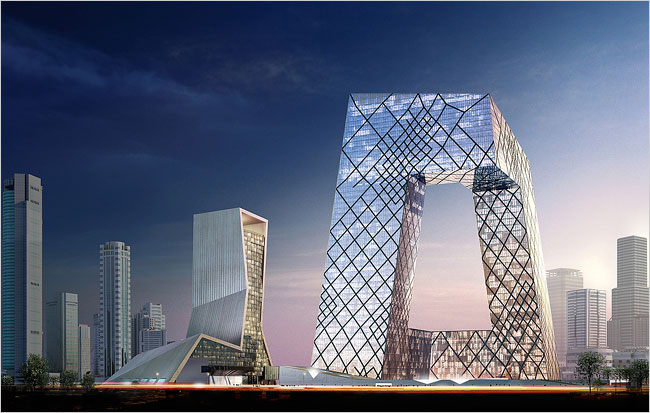

BLDGBLOG: Again in  [Image: The CCTV building, Beijing, by Rem Koolhaas/

[Image: The CCTV building, Beijing, by Rem Koolhaas/ BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in your work – and

BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in your work – and  BLDGBLOG: When you go there, who exactly are you networking with? Architects? Civil servants?

BLDGBLOG: When you go there, who exactly are you networking with? Architects? Civil servants?

BLDGBLOG: Finally, as far as your new job goes – becoming

BLDGBLOG: Finally, as far as your new job goes – becoming  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: An artificial waterfall below the surface of the earth, photographed by

[Image: An artificial waterfall below the surface of the earth, photographed by  [Image: Tower of ladders and platforms, photographed by

[Image: Tower of ladders and platforms, photographed by  [Image: Black and white topology of intake valves, photographed by

[Image: Black and white topology of intake valves, photographed by

[Images: The human encounter with geometry by torchlight, photographed by

[Images: The human encounter with geometry by torchlight, photographed by  [Image: Instrumental curvature, photographed by

[Image: Instrumental curvature, photographed by  [Image: Shining tunnelwork of the future, photographed by

[Image: Shining tunnelwork of the future, photographed by  [Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for

[Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for  [Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via

[Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via  [Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via

[Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via  [Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by

[Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by  [Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by

[Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by  BLDGBLOG: The

BLDGBLOG: The  [Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by

[Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by  [Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by

[Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by  [Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by

[Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by

[Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for  [Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

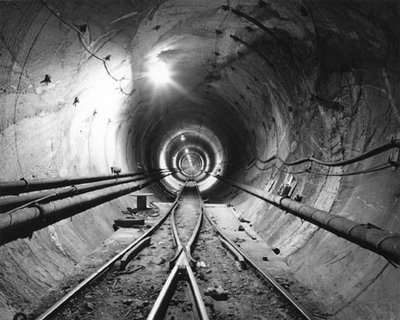

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].