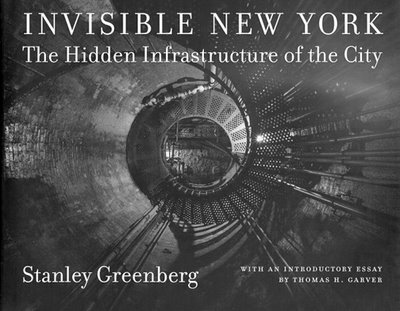

Whilst BLDGBLOG was out exploring the underside of Manhattan, from the island’s faucets to its outer city aqueducts, an email came through from Stanley Greenberg, photographic author of both Invisible New York: The Hidden Infrastructure of the City and Waterworks: A Photographic Journey through New York’s Hidden Water System.

He’s a fascinating guy.

“I started photographing the city’s infrastructure in 1992,” he explained, “after working in NYC government in the 1980s. A few things led me to the project. I felt that the water system was being taken for granted, partially because the government is so secretive about it. Places that were built as parks and destinations were now off-limits to everyone – especially after 9/11. I’m concerned that so many public spaces are being withdrawn from our society.”

The secrecy that now surrounds New York’s aquatic infrastructure, however, is “really just an acceleration of a trend,” Greenberg continued. “City Tunnel No. 3, the new water tunnel, has been under construction since 1970, and its entryways are: 1) well hidden, and 2) built to withstand nuclear weapons. While there were always parts of the system that were open to the public, there were other parts that became harder and harder to see. But even worse, I think, is the idea that we don’t even deserve to know about the system in ways that are important to us. It’s that much easier to privatize the system (as Giuliani tried to do). The Parks Department here just signed a contract with a private developer to turn part of Randall’s Island into a water park, which will not only take away public space, and probably be an environmental disaster, but will also institute an entrance fee for something that was free before. We don’t know how well our infrastructure is being taken care of and we’re not allowed to know, because of ‘national security.’ So how do we know if we’re spending too little money to take care of it?”

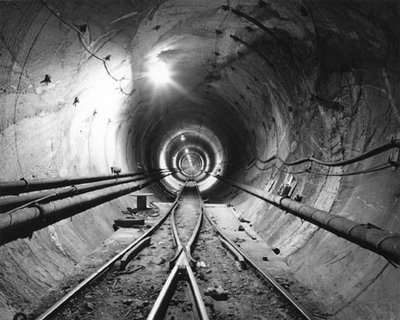

Greenberg’s photographic attraction is understandable. In his work, the New York City water supply reveals itself as a constellation of negative spaces: trapezoidal culverts, spillways, tunnels – cuts through the earth. His subject, in a sense, is terrain that is no longer there.

As Greenberg writes: “The water system today is an extraordinary web of places – beautiful landscapes, mysterious structures, and sites where the natural meets the man-made in enigmatic ways.”

These excavations, drained of their water, would form a networked monument to pure volume, inscribed into the bedrock of Hudson Valley.

“While the work is not meant to be a comprehensive record of the system,” Greenberg explained over email, “it is meant to make people think about this organism that stretches 1000 feet underground and 200 miles away. I did a lot of research, and spent some time helping to resurrect the Water Department’s archives, which had been neglected for 50 years, so I knew the system pretty well before I started. It got to the point where I could sense a water system structure without actually knowing what it was. My friends are probably tired of my telling them when they’re walking over a valve chamber, or over the place where City Tunnels 1, 2, and now 3 cross each other (near the Brooklyn Academy of Music), or some other obscure part of the system.”

Such tales of hidden topology, of course, do not risk boring BLDGBLOG. One imagines, in fact, a slight resonance to the ground, Manhattan’s sidewalks – or Brooklyn’s – very subtly trembling with echo to those who know what lies below. As if the water system could even have been built, say, as a subterranean extension to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a strange and amazing instrument drilled through rock, trumpeting with air pressure – a Symphony for the Hudson Valves, Bach’s Cantatas played through imperceptible reverberations of concrete and clay?

“I did all my photographs with permission,” Greenberg continues. “For one thing, it’s hard to sneak around with a 4×5 camera. For another, many of the places are extremely secure. I went back and forth over several years, sometimes being allowed in, other times being a pariah (and a threat to national security, according to the city, since I knew too much about the system). For some reason in 1998 I was given almost total access. I guess they realized I wasn’t going to give up, or that they would fare better if I were the one taking the pictures. I finished taking pictures in spring 2001. After 9/11, I’m sure I would have had little access – and in fact the city tried to stop me from publishing the book. I contacted curators, museum directors and some well-known lawyers; all offered their support. So when I told the city I would not back down, they gave up trying to stop me, and we went to press.”

You can buy the book here; and you can read about Stanley Greenberg’s work all over the place, including here, here, and here (with photographic examples), and even on artnet.

Meanwhile, Greenberg has a show, open till 20 May, 2006, at the Candace Dwan Gallery, NYC. There, you’ll see Greenberg’s more recent photographs of “contemporary architecture under construction. Included in the show are photographs of works by Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Steven Holl, Daniel Libeskind, Yoshio Taniguchi, Winka Dubbeldam, and Bernard Tschumi.”

Earlier: Faucets of Manhattan and London Topological.

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for  [Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].