[Image: Stephen Graham’s Cities Under Siege].

[Image: Stephen Graham’s Cities Under Siege].

In a 2003 paper for the Naval War College Review, author Richard J. Norton defined the term feral cities. “Imagine a great metropolis covering hundreds of square miles,” Norton begins, as if narrating the start of a film pitch. “Once a vital component in a national economy, this sprawling urban environment is now a vast collection of blighted buildings, an immense petri dish of both ancient and new diseases, a territory where the rule of law has long been replaced by near anarchy in which the only security available is that which is attained through brute power.”

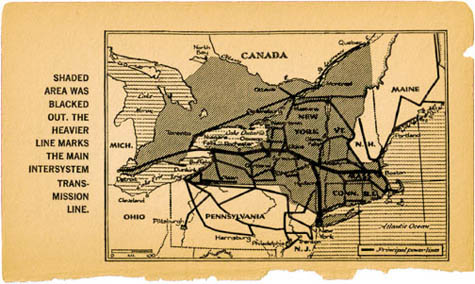

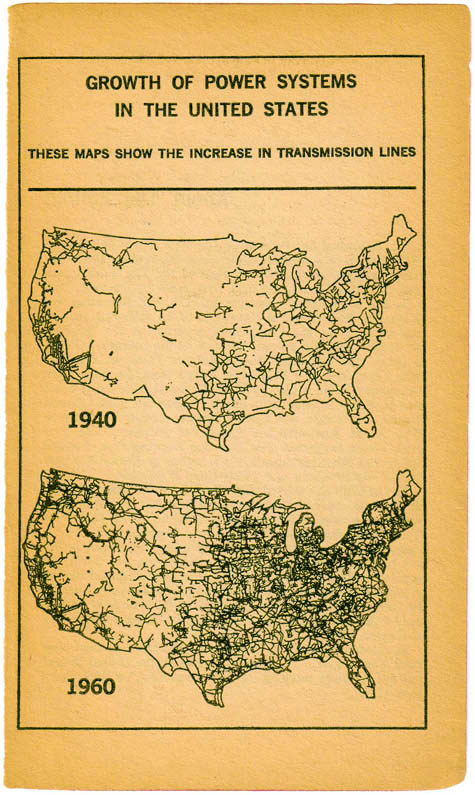

With the city’s infrastructure having collapsed long ago—or perhaps having never been built in the first place—there are no works of public sanitation, no sewers, no licensed doctors, no reliable food supply, no electricity. The feral city is a kind of return to medievalism, we might say, back to the future of a dark age for anyone but criminals, gangs, and urban warlords. It is a space of illiterate power—strength unresponsive to rationality or political debate.

From the perspective of a war planner or soldier, the feral city is also spatially impenetrable, a maze resistant to aerial mapping. Indeed, its “buildings, other structures, and subterranean spaces, would offer nearly perfect protection from overhead sensors, whether satellites or unmanned aerial vehicles,” Norton writes.

This is something Russell W. Glenn, formerly of the RAND Corporation—an Air Force think tank based in Southern California—calls “combat in Hell.” In his 1996 report of that name, Glenn pointed out that “urban terrain confronts military commanders with a synergism of difficulties rarely found in other environments,” many of which are technological. For instance, the effects of radio communications and global positioning systems can be radically limited by dense concentrations of architecture, turning what might otherwise be an exotic experience of pedestrian urbanism into a claustrophobic labyrinth inhabited by unseen enemy combatants.

Add to this the fact that military ground operations of the near future are more likely to unfold in places like Sadr City, Iraq—not in paragons of city planning like Vancouver—and you have an environment in which soldiers are as likely to die from tetanus, rabies, and wild dog attacks, Norton suggests, as from actual armed combat.

Put another way, as Mike Davis wrote in Planet of Slums, “the cities of the future, rather than being made out of glass and steel as envisioned by earlier generations of urbanists, are instead largely constructed out of crude brick, straw, recycled plastic, cement blocks, and scrap wood. Instead of cities of light soaring toward heaven, much of the twenty-first-century urban world squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay.”

But feral cities are one thing, cities under siege are something else.

[Images: The Fires by Joe Flood and Planet of Slums by Mike Davis].

[Images: The Fires by Joe Flood and Planet of Slums by Mike Davis].

In his new book Cities Under Siege, published just two weeks ago, geographer Stephen Graham explores “the extension of military ideas of tracking, identification and targeting into the quotidian spaces and circulations of everyday life,” including “dramatic attempts to translate long-standing military dreams of high-tech omniscience and rationality into the governance of urban civil society.” This is just part of a “deepening crossover between urbanism and militarism,” one that will only become more pronounced, Graham fears, over time.

One particularly fascinating example of this encroachment of “military dreams… into the governance of urban civil society” is actually the subject of a forthcoming book by Joe Flood. The Fires tells the story of “an alluring proposal” offered by the RAND Corporation, back in 1968, “to a city on the brink of economic collapse [New York City]: using RAND’s computer models, which had been successfully implemented in high-level military operations, the city could save millions of dollars by establishing more efficient public services.” But all did not go as planned:

Over the next decade—a time New York City firefighters would refer to as “The War Years”—a series of fires swept through the South Bronx, the Lower East Side, Harlem, and Brooklyn, gutting whole neighborhoods, killing more than two thousand people and displacing hundreds of thousands. Conventional wisdom would blame arson, but these fires were the result of something altogether different: the intentional withdrawal of fire protection from the city’s poorest neighborhoods—all based on RAND’s computer modeling systems.

In any case, Graham’s interest is in the city as target, both of military operations and of political demonization. In other words, cities themselves are portrayed “as intrinsically threatening or problematic places,” Graham writes, and thus feared as sites of economic poverty, moral failure, sexual transgression, rampant criminality, and worse (something also addressed in detail by Steve Macek’s book Urban Nightmares). All cities, we are meant to believe, already exist in a state of marginal ferality. I’m reminded here of Frank Lloyd Wright’s oft-repeated remark that “the modern city is a place for banking and prostitution and very little else.”

In some of the book’s most interesting sections, Graham tracks the growth of urban surveillance and the global “homeland security market.” He points out that major urban events—like G8 conferences, the Olympics, and the World Cup, among many others—offer politically unique opportunities for the installation of advanced tracking, surveillance, and facial-recognition technologies. Deployed in the name of temporary security, however, these technologies are often left in place when the event is over: a kind of permanent crisis, in all but name, takes over the city, with remnant, military-grade surveillance technologies gazing down upon the streets (and embedded in the city’s telecommunications infrastructure). A moment of exception becomes the norm.

Graham outlines a number of dystopian scenarios here, including one in which “swarms of tiny, armed drones, equipped with advanced sensors and communicating with each other, will thus be deployed to loiter permanently above the streets, deserts, and highways” of cities around the world, moving us toward a future where “militarized techniques of tracking and targeting must permanently colonize the city landscape and the spaces of everyday life.”

In the process, any real distinction between a “homeland” and its “colonies” is irreparably blurred. Here, he quotes Michel Foucault: “A whole series of colonial models was brought back to the West, and the result was that the West could practice something resembling colonization, or an internal colonialism, on itself.” If it works in Baghdad, the assumption goes, then let’s try it out in Detroit.

This is just one of many “boomerang effects” from militarized urban experiments overseas, Graham writes.

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

But what does this emerging city—this city under siege—actually look like? What is its architecture, its urban design, its local codes? What is its infrastructure?

Graham has many evocative answers for this. The city under siege is a place in which “hard, military-style borders, fences and checkpoints around defended enclaves and ‘security zones,’ superimposed on the wider and more open city, are proliferating.”

Jersey-barrier blast walls, identity checkpoints, computerized CCTV, biometric surveillance and military styles of access control protect archipelagos of fortified social, economic, political or military centers from an outside deemed unruly, impoverished and dangerous. In the most extreme examples, these encompass green zones, military prisons, ethnic and sectarian neighborhoods and military bases; they are growing around strategic financial districts, embassies, tourist and consumption spaces, airport and port complexes, sports arenas, gated communities and export processing zones.

Cities Under Siege also extensively covers urban warfare, a topic that intensely interests me. From Graham’s chapter “War Re-Enters the City”:

Indeed, almost unnoticed within “civil” urban social science, a shadow system of military urban research is rapidly being established, funded by Western military research budgets. As Keith Dickson, a US military theorist of urban warfare, puts it, the increasing perception within Western militaries is that “for Western military forces, asymmetric warfare in urban areas will be the greatest challenge of this century… The city will be the strategic high ground—whoever controls it will dictate the course of future events in the world.”

Ralph Peters phrased this perhaps most dramatically when he wrote, back in 1996 for the U.S. Army War College Quarterly, that “the future of warfare lies in the streets, sewers, high-rise buildings, industrial parks, and the sprawl of houses, shacks, and shelters that form the broken cities of our world.” The future of warfare, that is, lies in feral cities.

In this context, Graham catalogs the numerous ways in which “aggressive physical restructuring,” as well as “violent reorganization of the city,” is used, and has been used throughout history, as a means of securing and/or controlling a city’s population. At its most extreme, Graham calls this “place annihilation.” The architectural redesign of cities can thus be used as a military policing tactic as much as it can be discussed as a topic in academic planning debates. There are clearly echoes of Eyal Weizman in this.

On one level, these latter points are obvious: small infrastructural gestures, like public lighting, can transform alleyways from zones of impending crime to walkways safe for pedestrian use—and, in the process, expand political control and urban police presence into that terrain. But, as someone who does not want to be attacked in an alleyway any time soon, I find it very positive indeed when the cityscape around me becomes both safer by design and better policed. Equally obvious, though, when these sorts of interventions are scaled-up—from public lighting, say, to armed checkpoints in a militarized reorganization of the urban fabric—then something very drastic, and very wrong, is occurring in the city. Instead of a city simply with more cops (or fire departments), you begin a dark transition toward a “city under siege.”

I could go on at much greater length about all of this—but suffice it to say that Cities Under Siege covers a huge array of material, from the popularity of SUVs in cities to the blast-wall geographies of Baghdad, from ASBOs in London to drone helicopters in the skies above New York. Raytheon’s e-Borders program opens the book, and Graham closes it all with a discussion of “countergeographies.”

(Parts of this post, on feral cities, originally appeared in AD: Architectures of the Near Future, edited by Nic Clear).

[Image: “Minimal Republic nº3, Area: 100 m², Border: square, 10m side, defined with rope tied to pickaxes around a square of crushed rye, Population: 1 inhabitant, Location: 41.298691º, -3.400101º, Start: July 30, 2015, 19:15, End: July 31, 2015, 11:38,” from Minimal Republics by Rubén Martín de Lucas, via LensCulture.]

[Image: “Minimal Republic nº3, Area: 100 m², Border: square, 10m side, defined with rope tied to pickaxes around a square of crushed rye, Population: 1 inhabitant, Location: 41.298691º, -3.400101º, Start: July 30, 2015, 19:15, End: July 31, 2015, 11:38,” from Minimal Republics by Rubén Martín de Lucas, via LensCulture.] [Image: “Minimal Republic nº2, Area: 100 m², Population: 1 inhabitant, Border: equilateral triangle, side 15.19 m made of wooden slats assembled, Location: 40.039637º, -5.1146942º, Start: July 23, 2015, 12:21, End: July 23, 2015, 21:48,” from Minimal Republics by Rubén Martín de Lucas, via LensCulture.]

[Image: “Minimal Republic nº2, Area: 100 m², Population: 1 inhabitant, Border: equilateral triangle, side 15.19 m made of wooden slats assembled, Location: 40.039637º, -5.1146942º, Start: July 23, 2015, 12:21, End: July 23, 2015, 21:48,” from Minimal Republics by Rubén Martín de Lucas, via LensCulture.] [Image: “Minimal Republic nº8, Area: 100 m2, Border: circle of 5.64 m radius of stacked stubble, Population: 1 inhabitant, Location: 41.4152292, -3.3632866, Start: September 8, 2017, 18:41, End: September 9, 2017, 18:40,” from Minimal Republics by Rubén Martín de Lucas, via LensCulture.]

[Image: “Minimal Republic nº8, Area: 100 m2, Border: circle of 5.64 m radius of stacked stubble, Population: 1 inhabitant, Location: 41.4152292, -3.3632866, Start: September 8, 2017, 18:41, End: September 9, 2017, 18:40,” from Minimal Republics by Rubén Martín de Lucas, via LensCulture.] [Image: An engraving of mining, from Diderot’s

[Image: An engraving of mining, from Diderot’s  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: Federal lands near Boulder, Utah; Instagram by

[Image: Federal lands near Boulder, Utah; Instagram by

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Scout” UAV, via

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of a “Scout” UAV, via

[Image: “Riggers install a lightning rod” atop the Empire State Building “in preparation for an investigation into lightning by scientists of the General Electric Company” (1947), via the

[Image: “Riggers install a lightning rod” atop the Empire State Building “in preparation for an investigation into lightning by scientists of the General Electric Company” (1947), via the  [Image: Lightning storm over Boston; via

[Image: Lightning storm over Boston; via  [Image: Lightning via

[Image: Lightning via

[Image: Liberian security forces implement “a quarantine of the West Point slum, stepping up the government’s fight to stop the outbreak and unnerving residents.” Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Liberian security forces implement “a quarantine of the West Point slum, stepping up the government’s fight to stop the outbreak and unnerving residents.” Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: Neigborhood-scale quarantine; photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Neigborhood-scale quarantine; photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: Enforcing quarantine; Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Enforcing quarantine; Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: A “quarantine house” in Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: A “quarantine house” in Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.  [Image: Quarantine station, Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: Quarantine station, Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.  [Image: Stephen Graham’s

[Image: Stephen Graham’s  [Images:

[Images:

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq]. [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From