“At a time when the country is demanding political change, a group of architects has set up a contest to redesign one of the most powerful icons of American government: the White House itself.” White House Redux on NPR.

Tag: Architecture

I was recently interviewed by National Public Radio’s On The Media for a show that aired this past weekend. We talked about architectural models, Die Hard, special effects and renderings, Saddam Hussein, Albert Speer, and so on. I sound pretty inarticulate, to be frank, but I’m still excited to have been on NPR. You can read a transcript of the show here, or you can download the MP3. The entire program was about urban and architectural space: check out all the segments through On The Media’s website.

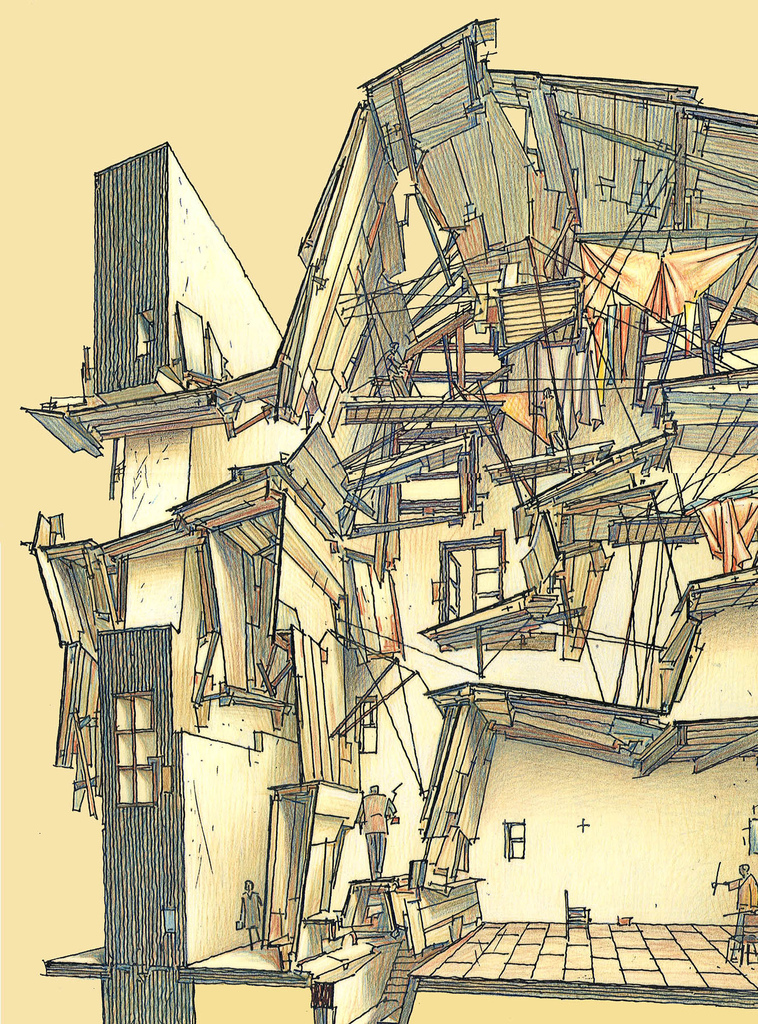

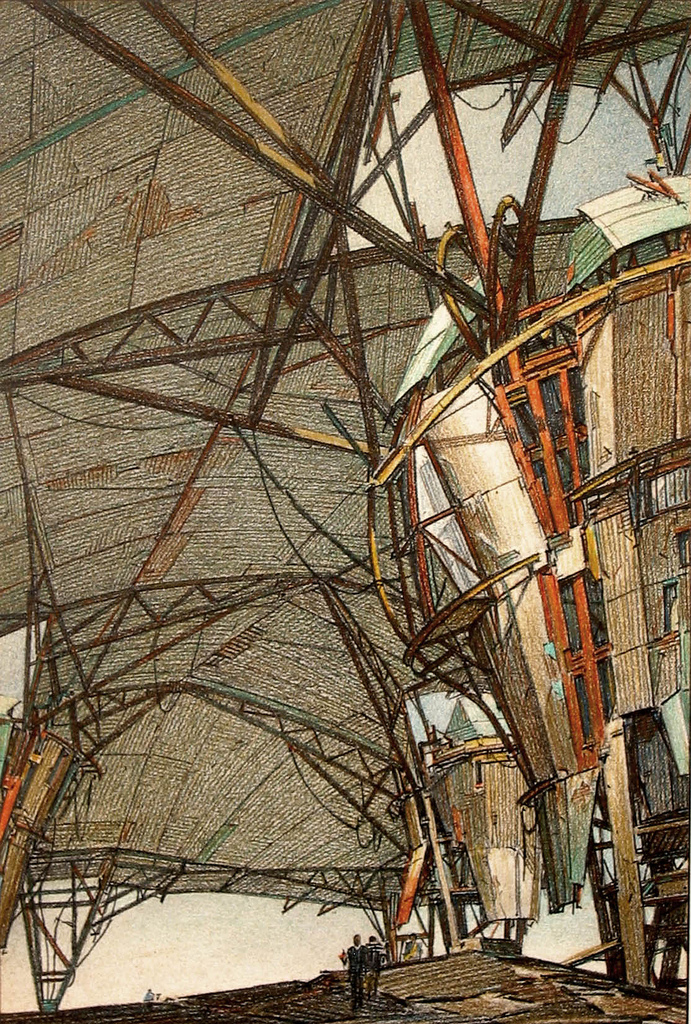

Game/Space: An Interview with Daniel Dociu

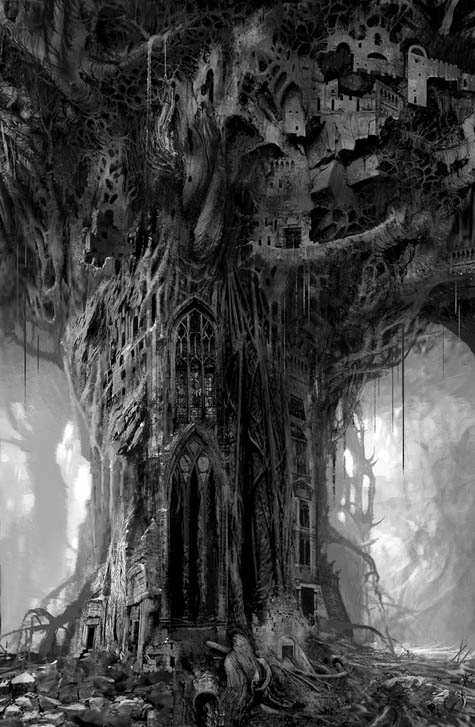

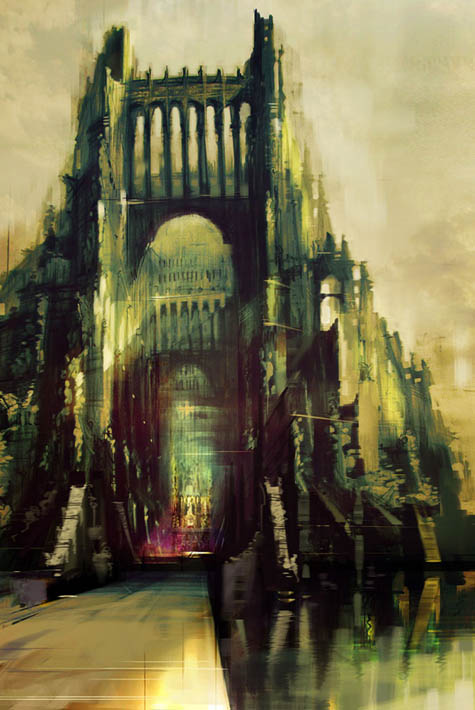

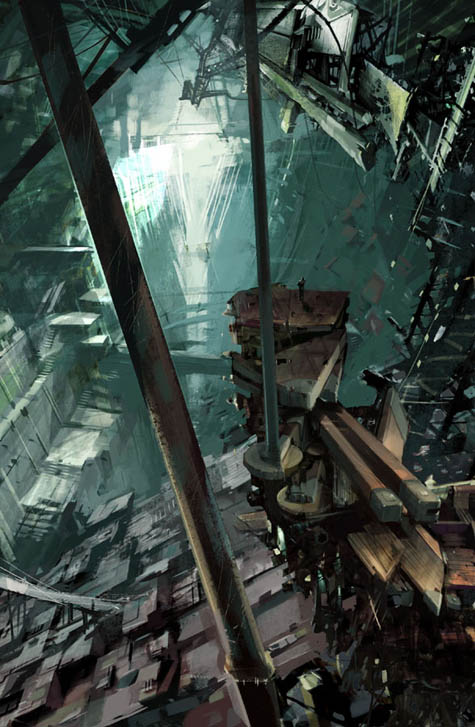

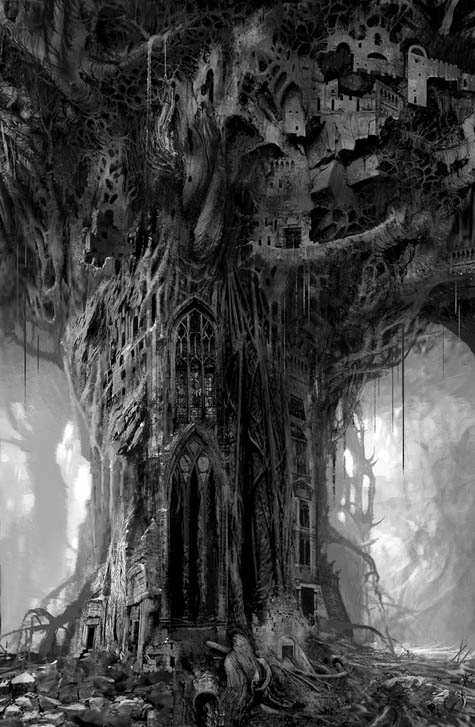

[Image: Daniel Dociu. View larger! This and all images below are Guild Wars content and materials, and are trademarks and/or copyrights of ArenaNet, Inc. and/or NCsoft Corporation, and are used with permission; all rights reserved].

[Image: Daniel Dociu. View larger! This and all images below are Guild Wars content and materials, and are trademarks and/or copyrights of ArenaNet, Inc. and/or NCsoft Corporation, and are used with permission; all rights reserved].

Seattle-based concept artist Daniel Dociu is Chief Art Director for ArenaNet, the North American wing of NCSoft, an online game developer with headquarters in Seoul. Most notably, Dociu heads up the production of game environments for Guild Wars – to which GameSpot gave 9.2 out of 10, specifically citing the game’s “gorgeous graphics” and its “richly detailed and shockingly gigantic” world.

Dociu has previously worked with Electronic Arts; he has an M.A. in industrial design; and he won both Gold and Silver medals for Concept Art at this year’s Spectrum awards

To date, BLDGBLOG has spoken with novelists, film editors, musicians, architects, photographers, historians, and urban theorists, among others, to see how architecture and the built environment have been used, understood, or completely reimagined from within those disciplines – but coverage of game design is something in which this site has fallen woefully short.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

So when I first saw Daniel Dociu’s work I decided to get in touch with him, and to ask him some questions about architecture, landscape design, and the creation of detailed online environments for games.

For instance, are there specific architects, historical eras, or urban designers who have inspired Dociu’s work? What about vice versa: could Dociu’s own beautifully rendered take on the built environment, however fantastical it might be, have something to teach today’s architecture schools? How does the game design process differ from – or perhaps resemble – that of producing “real” cities and buildings?

Of course, there are many types of games, and many types of game environments. The present interview focuses quite clearly on fantasy – and it does so not from the perspective of game play or of programming but from the visual perspective of architectural design.

After all, if Dociu’s buildings and landscapes are spaces that tens of thousands of people have experienced – far more than will ever experience whatever new home is featured in starchitects’ renderings cut and pasted from blog to blog this week – then surely they, too, should be subject to architectural discussion?

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

Further, at what point in the design process do architects themselves begin to consider action and narrative development – and would games be a viable way for them to explore the social use of their own later spaces?

What would a game environment designed by Rem Koolhaas, or Zaha Hadid, or FAT really look like – and could video games be an interesting next step for professional architectural portfolios? You want to see someone’s buildings – but you don’t look at a book, or at a PDF, or at a Flickr set of JPGs: you instead enter an entire game world, stocked only with spaces those architects have created.

Richard Rogers is hired to design Grand Theft Auto: South London.

Of course, these questions go far beyond the scope of this interview – but such a discussion would be well worth having.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

What appears below is an edited transcript of a conversation I had with Daniel Dociu about his work, and about the architecture of game design.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: First, I’d love to hear where you look for inspiration or ideas when you sit down to work on a project. Do you look at different eras of architecture, or at specific buildings, or books, or paintings – even other video games?

Daniel Dociu: Anything but video games! [laughs] I don’t want to copy anybody else.

Architecture has always made a strong impression on me – though I can’t think of one particular style or era or architect where I would say: “This is it. This is the one and only influence that I’ll let seep into my work.” Rather, I just sort of store in my memory everything that has ever made an impression on me, and I let it simmer there and blend with everything else. Eventually some things will resurface and come back, depending on the particular assignment I’m working on.

But I look back all the way to the dawn of mankind: to ruins, and Greek architecture, and Mycenean architecture, all the way up to the architecture of the Crusades, and castles in North Africa, and the Romanesque and Gothic and Baroque and Rococo – even to neo-Classical and art deco and Bauhaus and Modernist. I mean, there are bits and pieces here and there that make a strong impression on me, and I blend them – but that’s the beauty of games. You don’t have to be stylistically pure, or even coherent. You can afford a certain eclecticism to your work. It’s a more forgiving medium. I can blend elements from the Potala Palace in Tibet with, say, La Sagrada Família, Antoni Gaudí’s cathedral. I really take a lot of liberties with whatever I can use, wherever I can find it.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top, middle, and bottom].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top, middle, and bottom].

BLDGBLOG: Of course, if you were an architecture student and you started to design buildings that looked like Gothic cathedrals crossed with the Bauhaus, everybody outside of architecture school might love it, but inside your studio –

Dociu: You’d be crucified! [laughs]

[Image: Daniel Dociu; larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; larger!].

BLDGBLOG: No one would take you seriously. It’d be considered unimaginative – even kitsch.

Dociu: Absolutely. That’s probably why I chose to work in this field. There’s just so much creative freedom. I mean, sure, you do compromise and you do tailor your ideas, and the scope of your design, to the needs of the product – but, still, there’s a lot of room to push.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

BLDGBLOG: So how much description are you actually given? When someone comes to you and says, “I need a mine, or a mountain, or a medieval city” – how much detail do they really give before you have to start designing?

Dociu: That’s about the amount of information I get.

Game designers lay things out according to approximate locations – this tribe goes here, this tribe goes there, we need a village here, we need an extra reason for a conflict along this line, or a natural barrier here, whether it’s a river or a mountain, or we need an artificial barrier or a bridge. That’s pretty much the level at which I prefer for them to give me input, and I take it from there. Most of my work recently has been focusing around environments and unique spaces that fulfill whatever the game play requires – providing a memorable background for that experience.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: So somebody just says, “we need a castle,” and you go design it?

Dociu: Usually I don’t put pen to paper, figuratively speaking, until I have an idea. I don’t believe in just doodling and hoping for things to happen. More often than not, I think about a sentiment or an emotion that I’m trying to capture with an environment – and then I go back in my mind through images or places that have made a strong impression on me, and I see if anything resonates. I then start doing research along those lines. Only once did I have a pretty strong formal solution – an actual design or spatial relationship, an architectural arrangement of the elements – before that emotion crystallized.

But do I want something to be awe-inspiring, daunting, unnerving? That’s what I work on first – to have that sentiment clarify itself. I don’t start just playing with shapes to see what might result. Most of my work is pretty simple, so clarity and simplicity is important to me; my ideas aren’t very sophisticated, as far as requiring complex technical solutions. They’re pretty simple. I try to achieve emotional impact through rather simple means.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: one, two, three, four, five, and six].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: one, two, three, four, five, and six].

BLDGBLOG: Do you ever find that you’ve designed something where the architecture itself sort of has its own logic – but the logic of the game calls for something else? So you have to design against your own sense of the design for the sake of game play?

Dociu: Oh, absolutely – more often than not.

To make an environment work for a game, you have to redesign your work – and I do sometimes feel bad about the missed opportunities. These may not be ideas that would necessarily make great architecture in real life, but these ideas often take a more uncompromising form – a more pure form – before you have to change them. When these environments need to be adapted to the game, they lose some of that impact.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: I’d love to focus on a few specific images now, to hear what went into them – both conceptually and technically. For instance, the image I’m looking at here is called Skybridge. Could you tell me a little bit more about that?

Dociu: Sure. The request there was for a tribe that’s been trying to isolate itself from the conflict, and the tensions, and the political unrest of the world around it. So they find this canyon in the mountains – and I was picturing the mountains kind of like the Andes: really steep and shard-like. They pick one of these canyons and they build a structure that’s floating above the valley below – to physically remove themselves from the world. That was the premise.

I wanted a structure that looked light and airy, as if it’s trying to float, and I chose the shapes you see for their wing-like quality. Everything is very thin, supported by a rather minimalist structure of cables. It’s supposed to be the habitat for an entire tribe that chooses to detach themselves from society, as much as they can.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: You’ve designed a lot of structures in the sky, like airborne utopias – for instance, the Floating Mosque and the Floating Temple. Was there a similar concept behind those images?

Dociu: Well, yes and no. The reasons behind those examples were quite different. First, floating mosques were my attempt to deal with what is a rather obnoxious cliché in games – which is floating castles. Every game has a floating castle. You know, I really hate that!

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: [laughs] So these are actually your way of dealing with a game design cliché?

Dociu: I was trying to find a somewhat elegant and satisfying solution to an uninteresting request.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: And what about Pagodas?

Dociu: The story there was that this was a city for the elite. It was built in a pool of water and it was surrounded by desert. Water is in really high demand in this world, but these guys are kind of controlling the water supply. The real estate on these rock formations is limited, though, so they were forced to build vertically and use every inch of rock to anchor their structures. So it’s about people over-building, and about clinging onto resources, and about greed.

That doesn’t touch on the game in its entirety – but that’s the story behind the image.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: Finally, what about the Petrified Tree?

Dociu: That was part of another chapter in our game. We thought that there should be some kind of cataclysm – or an event, a curse – that turns the oceans into jade and the forests into stone. We had nomads traveling the jade sea in these big contraptions, like machines.

So the petrified forest was a gigantic forest that got turned into stone, and the people who were happily inhabiting that forest had to find ways to carve dwellings into the trees: different ways of shaping the natural stone formations and giving them some kind of functionality – arches, bridges, dwellings, and so on and so forth. It was a blend of organic and manmade structures.

At that particular point in time, quite a few of my pieces were the result of my fascination with the Walled City of Kowloon. I was really sad to see that demolished, and this was kind of my desperate attempt to hold onto it! I was incorporating that sensibility into a lot of my pieces, knowing it was going to be gone for good.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

Thanks again to Daniel Dociu for taking the time to have this conversation. Meanwhile, many, many more images are available on his website – and in this Flickr set.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

(Daniel Dociu’s work originally spotted on io9).

Forgotten Architects

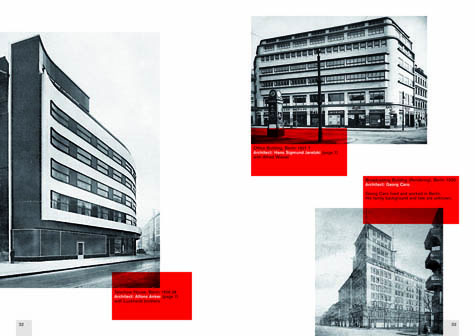

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

Earlier this month, Pentagram released a pamphlet called Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, German Jewish architects created some of the greatest modern buildings in Germany, mainly in the capital Berlin. A law issued by the newly elected German National Socialist Government in 1933 banned all of them from practicing architecture in Germany. In the years after 1933, many of them managed to emigrate, while many others were deported or killed under Hitler’s regime. Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects is a survey of 43 of these architects and their groundbreaking work.

The work thus presented is based on research performed by Myra Warhaftig, and it is available both online and in a small, beautifully designed booklet. Four of the images you see here are spreads from that publication, courtesy of Pentagram.

[Image: Spreads from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: Spreads from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

As Warhaftig wrote in an introduction to the project:

On 1 November 1933, a few months after the German National Socialist Government came to power, a decree was issued banning Jewish architects from the Reichskulturkammer für bildende Künste, the state-governed association of fine art to which membership was required to practice architecture. Their academic titles were revoked and they were denied the use of the professional title “architect.” Just short of two years later, on 15 September 1935, another law was adopted, further excluding from the association all so-called Half-Jews and those who were married to Jews. In total, nearly 500 architects were affected by the ban and forced to leave Germany. Those who stayed had to go into hiding or were deported to ghettos or concentration camps.

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

[Image: A spread from Pentagram Papers 37: Forgotten Architects].

She continues:

After long and circuitous routes, I have succeeded in locating relatives of the deceased architects. Scattered across all continents, they were able to offer additional authentic material. These historical documents and biographies, as well as photographs of the architects’ buildings, are published for the first time in my book German Jewish Architects Before and After 1933: The Lexicon.

Many of the buildings these architects produced were absolutely extraordinary – and, frankly, it seems impossible not to look at these images and judge 20th century Germany in light of the catastrophic stupidities that led to its murderous exile of the creative classes, whether those were physicists, novelists, abstract expressionists, or even architect members of the Bauhaus.

Indeed, it’s impossible to look at today’s European landscape in general and not spot absences, or losses, voids here and there punctuating the 21st century town and city.

[Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by Georg Falck; photo via Archive Dr. Hagspiegel].

[Image: Tietz Department Store in Solingen (1930?), designed by Georg Falck; photo via Archive Dr. Hagspiegel].

The images here show some of the buildings that Myra Warhaftig’s research, performed up until her death only three weeks ago, uncovered. Many more shots are available on Pentagram’s project website.

[Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by Moritz Hadda (1929); Terraced Houses, Berlin, by Alfons Anker (1929-30); Arnold Zweig Residence (1929-30), Eisner Residence (1927), and Schulze Residence (1928-29), all in Berlin and all magnificent designs by architect Harry Rosenthal; and a police station in Berlin by Richard Scheibner (1930-31)].

[Images: Showcase House, Werkbundsiedlung Breslow, by Moritz Hadda (1929); Terraced Houses, Berlin, by Alfons Anker (1929-30); Arnold Zweig Residence (1929-30), Eisner Residence (1927), and Schulze Residence (1928-29), all in Berlin and all magnificent designs by architect Harry Rosenthal; and a police station in Berlin by Richard Scheibner (1930-31)].

Referring to the architects whose work is featured in the above seven photographs:

In 1933, Georg Falck fled with his family to the Netherlands: “In Amsterdam they survived in hiding until the end of the war. Falck died in a New York Hospital in May 1947, just six weeks after he and his family had emigrated to the USA.”

Alfons Anker‘s business partners joined the Nazi party in 1933; six years later, he “managed to flee to Sweden, but never succeeded in re-establishing his career as an architect. Anker died in Stockholm in 1958.”

Harry Rosenthal, architect of three houses featured above, “was born in Posen (today Poznan, Poland) in 1892. He lived and worked in Berlin where he ran a successful architectural practice. In 1933 he managed to flee to Palestine, but suffered from the subtropical climate. In 1938 he emigrated to England, where despite numerous attempts, he did not manage to re-establish his architectural career. He died in London in 1966.”

In 1941, Moritz Hadda “was deported to an unknown location.”

Richard Scheibner‘s “fate is unknown.”

(Thanks to Michael Bierut and Kurt Koepfle at Pentagram for sending the booklet and spreads).

Psychology at Depth

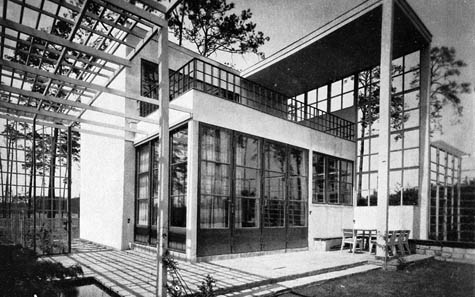

As published by Science and Mechanics in November 1931, the depthscraper was proposed as a residential engineering solution for surviving earthquakes in Japan.

As published by Science and Mechanics in November 1931, the depthscraper was proposed as a residential engineering solution for surviving earthquakes in Japan.

The subterranean building, “whose frame resembles that of a 35-story skyscraper of the type familiar in American large cities,” would actually be constructed “in a mammoth excavation beneath the ground.”

Only a single story protrudes above the surface; furnishing access to the numerous elevators; housing the ventilating shafts, etc.; and carrying the lighting arrangements… The Depthscraper is cylindrical; its massive wall of armored concrete being strongest in this shape, as well as most economical of material. The whole structure, therefore, in case of an earthquake, will vibrate together, resisting any crushing strain. As in standard skyscraper practice, the frame is of steel, supporting the floors and inner walls.

My first observation here is actually how weird the punctuational style of that paragraph is. Why all the commas and semicolons?

My second thought is that this thing combines about a million different themes that interest me: underground engineering, seismic activity, redistributed sunlight through complicated systems of mirrors, architectural speculation, disastrous social planning, etc. etc.

In J.G. Ballard’s hilariously excessive 1975 novel High-Rise – one of the most exciting books of architectural theory, I’d suggest, published in the last fifty years – we read about the rapid descent into chaos that befalls a brand new high-rise in London. Ballard writes that “people in high-rises tend not to care about tenants more than two floors below them.” Indeed, the very design of the building “played into the hands of the most petty impulses” – till “deep-rooted antagonisms,” assisted by chronic middle-class sexual boredom and insomnia, “were breaking through the surface of life within the high-life at more and more points.”

The residents are doomed: “Like a huge and aggressive malefactor, the high-rise was determined to inflict every conceivable hostility upon them.” One of the characters even “referred to the high-rise as if it were some kind of huge animate presence , brooding over them and keeping a magisterial eye on the events taking place.”

My point is simply that it doesn’t take very much to re-imagine Ballard’s novel set in a depthscraper: what strange antagonisms might break out in a buried high-rise?

Living underground, then, could perhaps be interpreted as a kind of avant-garde psychological experiment – experiential gonzo psychiatry.

I’m reminded here of the bunker psychology explored by Tom Vanderbilt in his excellent book Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America.

In the midst of a long, and fascinating, tour through the 20th century’s wartime underworlds, Vanderbilt writes of how “the confined underground space becomes a concentrated breeding ground for social dysfunction as the once-submerged id rages unchecked.” Living inside “massive underground fortifications” – whether fortified against enemy attack or against spontaneous movements of the earth’s surface – might even produce new psychiatric conditions, Vanderbilt writes. There were rumors of “‘concretitis’ and other strange new ‘bunker’ maladies” breaking out amidst certain military units garrisoned underground.

What future psychologies might exist, then, in these depthscrapers built along active faultlines?

Comparative Planetology: An Interview with Kim Stanley Robinson

[Image: The face of Nicholson Crater, Mars, courtesy of the ESA].

[Image: The face of Nicholson Crater, Mars, courtesy of the ESA].

According to The New York Times Book Review, the novels of Nebula and Hugo Award-winning author Kim Stanley Robinson “constitute one of the most impressive bodies of work in modern science fiction.” I might argue, however, that Robinson is fundamentally a landscape writer.

That is, Robinson’s books are not only filled with descriptions of landscapes – whole planets, in fact, noted, sensed, and textured down to the chemistry of their soils and the currents in their seas – but his novels are often about nothing other than vast landscape processes, in the midst of which a few humans stumble along. “Politics,” in these novels, is as much a question of social justice as it is shorthand for learning to live in specific environments.

In his most recent trilogy – Forty Signs of Rain, Fifty Degrees Below, and Sixty Days and Counting – we see the earth becoming radically unlike itself through climate change. Floods drown the U.S. capital; fierce winter ice storms leave suburban families powerless, in every sense of the word; and the glaciers of concrete and glass that we have mistaken for civilization begin to reveal their inner weaknesses.

In his most recent trilogy – Forty Signs of Rain, Fifty Degrees Below, and Sixty Days and Counting – we see the earth becoming radically unlike itself through climate change. Floods drown the U.S. capital; fierce winter ice storms leave suburban families powerless, in every sense of the word; and the glaciers of concrete and glass that we have mistaken for civilization begin to reveal their inner weaknesses.

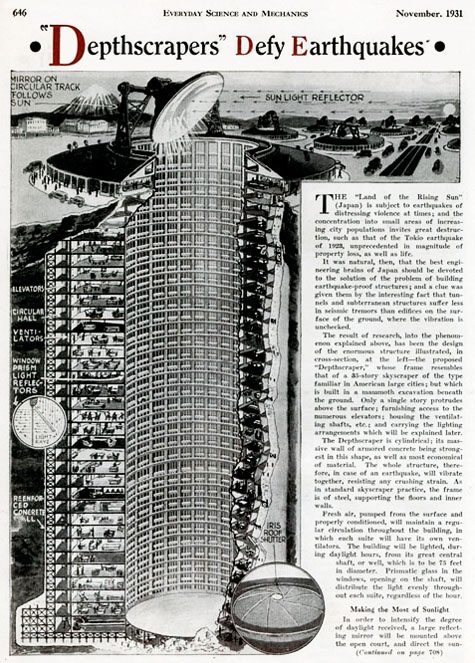

The stand-alone novel Antarctica documents the cuts, bruises, and theoretical breakthroughs of environmental researchers as they hike, snowshoe, sledge, belay, and fly via helicopter over the fractured canyons and crevasses of the southern continent. They wander across “shear zones” and find rooms buried in the ice, natural caves linked together like a “shattered cathedral, made of titanic columns of driftglass.”

Meanwhile, in Robinson’s legendary Mars Trilogy – Red Mars, Blue Mars, and Green Mars – the bulk of the narrative is, again, complete planetary transformation, this time on Mars. The Red Planet, colonized by scientists, is deliberately remade – or terraformed – to be climatically, hydrologically, and agriculturally suited for human life. Yet this is a different kind of human life – it, too, has been transformed: politically and psychologically.

In his recent book Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, Fredric Jameson devotes an entire chapter to Robinson’s Mars Trilogy. Jameson writes that “utopia as a form is not the representation of radical alternatives; it is rather simply the imperative to imagine them.”

Across all his books, Robinson is never afraid to imagine these radical alternatives. Indeed, in the interview posted below he explains that “I’ve been working all my career to try to redefine utopia in more positive terms – in more dynamic terms.”

In the following interview, then, Kim Stanley Robinson talks to BLDGBLOG about climate change, from Hurricane Katrina to J.G. Ballard; about the influence of Greek island villages on his descriptions of Martian base camps; about life as a 21st century primate in the 24/7 “techno-surround”; how we must rethink utopia as we approach an age without oil; whether “sustainability” is really the proper thing to be striving for; and what a future archaeology of the space age might find.

In the following interview, then, Kim Stanley Robinson talks to BLDGBLOG about climate change, from Hurricane Katrina to J.G. Ballard; about the influence of Greek island villages on his descriptions of Martian base camps; about life as a 21st century primate in the 24/7 “techno-surround”; how we must rethink utopia as we approach an age without oil; whether “sustainability” is really the proper thing to be striving for; and what a future archaeology of the space age might find.

This interview also includes previously unpublished photos by Robinson himself, taken in Greece and Antarctica.

BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in the possibility that literary genres might have to be redefined in light of climate change. In other words, a novel where two feet of snow falls on Los Angeles, or sand dunes creep through the suburbs of Rome, would be considered a work of science fiction, even surrealism, today; but that same book, in fifty years’ time, could very well be a work of climate realism, so to speak. So if climate change is making the world surreal, then what it means to write a “realistic” novel will have to change. As a science fiction novelist, does that affect how you approach your work?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, I’ve been saying this for a number of years: that now we’re all living in a science fiction novel together, a book that we co-write. A lot of what we’re experiencing now is unsurprising because we’ve been prepped for it by science fiction. But I don’t think surrealism is the right way to put it. Surrealism is so often a matter of dreamscapes, of things becoming more than real – and, as a result, more sublime. You think, maybe, of J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World, and the way that he sees these giant catastrophes as a release from our current social set-up: catastrophe and disaster are aestheticized and looked at as a miraculous salvation from our present reality. But it wouldn’t really be like that.

I started writing about Earth’s climate change in the Mars books. I needed something to happen on Earth that was shocking enough to allow a kind of historical gap in which my Martians could realistically establish independence. I had already been working with Antarctic scientists who were talking about the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, and how unstable it might be – so I used that, and in Blue Mars I showed a flooded London. But after you get past the initial dislocations and disasters, what you’ve got is another landscape to be inhabited – another situation that would have its own architecture, its own problems, and its own solutions.

To a certain extent, later, in my climate change books, I was following in that mold with the flood of Washington DC. I wrote that scene before Katrina. After Katrina hit, my flood didn’t look the same. I think it has to be acknowledged that the use of catastrophe as a literary device is not actually adequate to talk about something which, in the real world, is often so much worse – and which comes down to a great deal of human suffering.

So there may have been surreal images coming out of the New Orleans flood, but that’s not really what we take away from it.

[Image: Refugees gather outside the Superdome, New Orleans, post-Katrina].

[Image: Refugees gather outside the Superdome, New Orleans, post-Katrina].

BLDGBLOG: Aestheticizing these sorts of disasters can also have the effect of making climate change sound like an adventure. In Fifty Degrees Below, for instance, you wrote: “People are already fond of the flood… It was an adventure. It got people out of their ruts.” The implication is that people might actually be excited about climate change. Is there a risk that all these reports about flooded cities and lost archipelagoes and new coastlines might actually make climate change sound like some sort of survivalist adventure?

Robinson: It’s a failure of imagination to think that climate change is going to be an escape from jail – and it’s a failure in a couple of ways.

For one thing, modern civilization, with six billion people on the planet, lives on the tip of a gigantic complex of prosthetic devices – and all those devices have to work. The crash scenario that people think of, in this case, as an escape to freedom would actually be so damaging that it wouldn’t be fun. It wouldn’t be an adventure. It would merely be a struggle for food and security, and a permanent high risk of being robbed, beaten, or killed; your ability to feel confident about your own – and your family’s and your children’s – safety would be gone. People who fail to realize that… I’d say their imaginations haven’t fully gotten into this scenario.

It’s easy to imagine people who are bored in the modern techno-surround, as I call it, and they’re bored because they have not fully comprehended that they’re still primates, that their brains grew over a million-year period doing a certain suite of activities, and those activities are still available. Anyone can do them; they’re simple. They have to do with basic life support and basic social activities unboosted by technological means.

And there’s an addictive side to this. People try to do stupid technological replacements for natural primate actions, but it doesn’t quite give them the buzz that they hoped it would. Even though it looks quite magical, the sense of accomplishment is not there. So they do it again, hoping that the activity, like a drug, will somehow satisfy the urge that it’s supposedly meant to satisfy. But it doesn’t. So they do it more and more – and they fall down a rabbit hole, pursuing a destructive and high carbon-burn activity, when they could just go out for a walk, or plant a garden, or sit down at a table with a friend and drink some coffee and talk for an hour. All of these unboosted, straight-forward primate activities are actually intensely satisfying to the totality of the mind-body that we are.

So a little bit of analysis of what we are as primates – how we got here evolutionarily, and what can satisfy us in this world – would help us to imagine activities that are much lower impact on the planet and much more satisfying to the individual at the same time. In general, I’ve been thinking: let’s rate our technologies for how much they help us as primates, rather than how they can put us further into this dream of being powerful gods who stalk around on a planet that doesn’t really matter to us.

Because a lot of these supposed pleasures are really expensive. You pay with your life. You pay with your health. And they don’t satisfy you anyway! You end up taking various kinds of prescription or non-prescription drugs to compensate for your unhappiness and your unhealthiness – and the whole thing comes out of a kind of spiral: if only you could consume more, you’d be happier. But it isn’t true.

I’m advocating a kind of alteration of our imagined relationship to the planet. I think it’d be more fun – and also more sustainable. We’re always thinking that we’re much more powerful than we are, because we’re boosted by technological powers that exert a really, really high cost on the environment – a cost that isn’t calculated and that isn’t put into the price of things. It’s exteriorized from our fake economy. And it’s very profitable for certain elements in our society for us to continue to wander around in this dream-state and be upset about everything.

The hope that, “Oh, if only civilization were to collapse, then I could be happy” – it’s ridiculous. You can simply walk out your front door and get what you want out of that particular fantasy.

[Image: New Orleans under water, post-Katrina; photographer unknown].

[Image: New Orleans under water, post-Katrina; photographer unknown].

BLDGBLOG: Mars has a long history as a kind of utopian destination – and, in that, your Mars trilogy is no exception. What is it about Mars that brings out this particular kind of speculation?

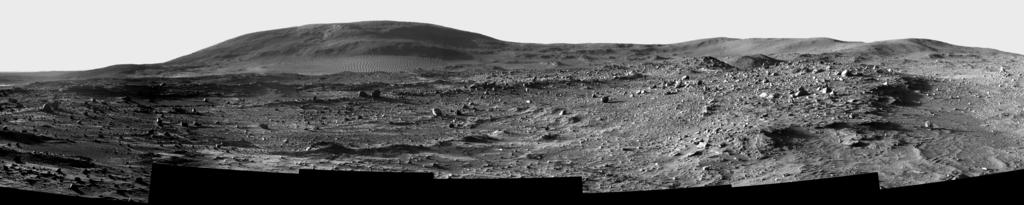

Robinson: Well, it brings up an unusual modern event that can happen in our mental landscapes, which is comparative planetology. That wasn’t really available to us before the modern era – really, until Viking.

One thing about Mars is that it’s a radically impoverished landscape. You start with nothing – the bare rock, the volatile chemicals that are needed for life, some water, and an empty landscape. That makes it a kind of gigantic metaphor, or modeling exercise, and it gives you a way to imagine the fundamentals of what we’re doing here on Earth. I find it is a very good thing to begin thinking that we are terraforming Earth – because we are, and we’ve been doing it for quite some time. We’ve been doing it by accident, and mostly by damaging things. In some ways, there have been improvements, in terms of human support systems, but there’s still so much damage, damage that’s gone unacknowledged or ignored, even when all along we knew it was happening. People kind of shrug and think: a) there’s nothing we can do about it, or b) maybe the next generation will be clever enough to figure it out. So on we go.

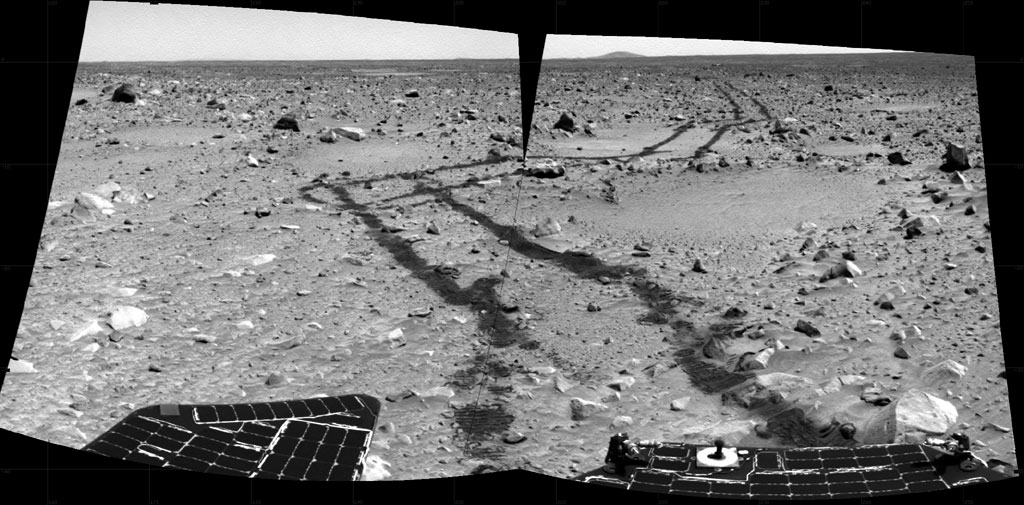

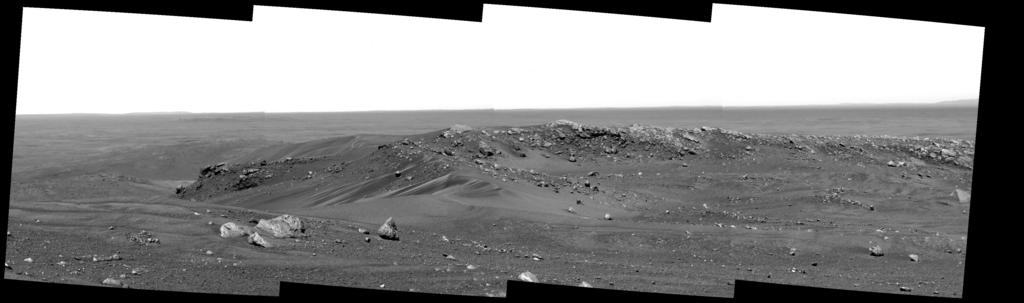

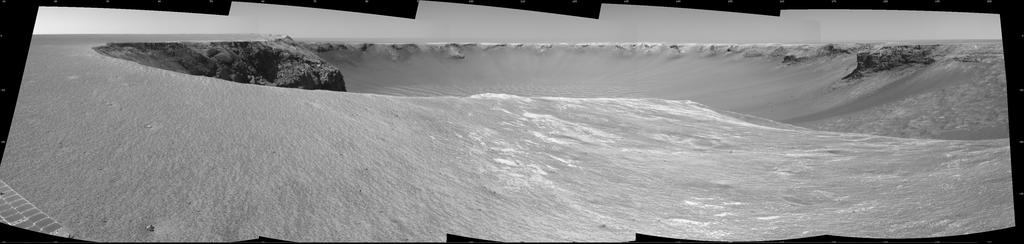

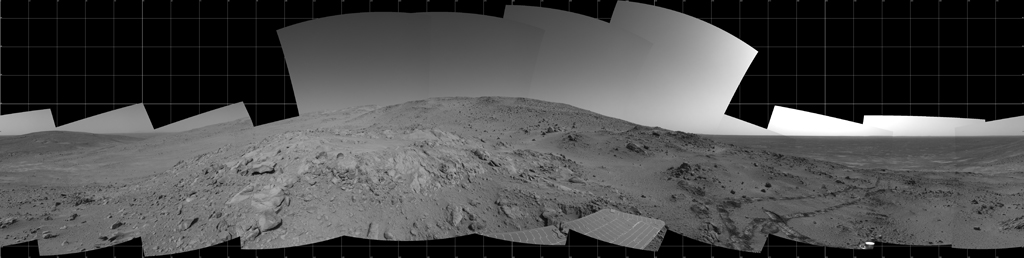

[Images: Mars, courtesy of NASA].

[Images: Mars, courtesy of NASA].

Mars is an interesting platform where we can model these things. But I don’t know that we’ll get there for another fifty years or so – and once we do get there, I think that for many, many years, maybe many decades, it will function like Antarctica does now: it will be an interesting scientific base that teaches us things and is beautiful and charismatic, but not important in the larger scheme of human history on Earth. It’s just an interesting place to study, that we can learn things from. Actually, for many years, Mars will be even less important to us than Antarctica, because the Antarctic is at least part of our ecosphere.

But if you think of yourself as terraforming Earth, and if you think about sustainability, then you can start thinking about permaculture and what permaculture really means. It’s not just sustainable agriculture, but a name for a certain type of history. Because the word sustainability is now code for: let’s make capitalism work over the long haul, without ever getting rid of the hierarchy between rich and poor and without establishing social justice.

Sustainable development, as well: that’s a term that’s been contaminated. It doesn’t even mean sustainable anymore. It means: let us continue to do what we’re doing, but somehow get away with it. By some magic waving of the hands, or some techno silver bullet, suddenly we can make it all right to continue in all our current habits. And yet it’s not just that our habits are destructive, they’re not even satisfying to the people who get to play in them. So there’s a stupidity involved, at the cultural level.

BLDGBLOG: In other words, your lifestyle may now be carbon neutral – but was it really any good in the first place?

Robinson: Right. Especially if it’s been encoding, or essentially legitimizing, a grotesque hierarchy of social injustice of the most damaging kind. And the tendency for capitalism to want to overlook that – to wave its hands and say: well, it’s a system in which eventually everyone gets to prosper, you know, the rising tide floats all boats, blah blah – well, this is just not true.

We should take the political and aesthetic baggage out of the term utopia. I’ve been working all my career to try to redefine utopia in more positive terms – in more dynamic terms. People tend to think of utopia as a perfect end-stage, which is, by definition, impossible and maybe even bad for us. And so maybe it’s better to use a word like permaculture, which not only includes permanent but also permutation. Permaculture suggests a certain kind of obvious human goal, which is that future generations will have at least as good a place to live as what we have now.

It’s almost as if a science fiction writer’s job is to represent the unborn humanity that will inherit this place – you’re speaking from the future and for the future. And you try to speak for them by envisioning scenarios that show them either doing things better or doing things worse – but you’re also alerting the generations alive right now that these people have a voice in history.

The future needs to be taken into account by the current system, which regularly steals from it in order to pad our ridiculous current lifestyle.

[Images: (top) Michael Reynolds, architect. Turbine House, Taos, New Mexico. Photograph © Michael Reynolds, 2007. (bottom) Steve Baer, designer. House of Steve Baer, Corrales, New Mexico, 1971. Photography © Jon Naar, 1975/2007. Courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, from their excellent, and uncannily well-timed, exhibition 1973: Sorry, Out of Gas].

[Images: (top) Michael Reynolds, architect. Turbine House, Taos, New Mexico. Photograph © Michael Reynolds, 2007. (bottom) Steve Baer, designer. House of Steve Baer, Corrales, New Mexico, 1971. Photography © Jon Naar, 1975/2007. Courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, from their excellent, and uncannily well-timed, exhibition 1973: Sorry, Out of Gas].

BLDGBLOG: When it actually comes to designing the future, what will permaculture look like? Where will its structures and ideas come from?

Robinson: Well, at the end of the 1960s and through the 70s, what we thought – and this is particularly true in architecture and design terms – was: OK, given these new possibilities for new and different ways of being, how do we design it? What happens in architecture? What happens in urban design?

As a result of these questions there came into being a big body of utopian design literature that’s now mostly obsolete and out of print, which had no notion that the Reagan-Thatcher counter-revolution was going to hit. Books like Progress As If Survival Mattered, Small Is Beautiful, Muddling Toward Frugality, The Integral Urban House, Design for the Real World, A Pattern Language, and so on. I had a whole shelf of those books. Their tech is now mostly obsolete, superceded by more sophisticated tech, but the ideas behind them, and the idea of appropriate technology and alternative design: that needs to come back big time. And I think it is.

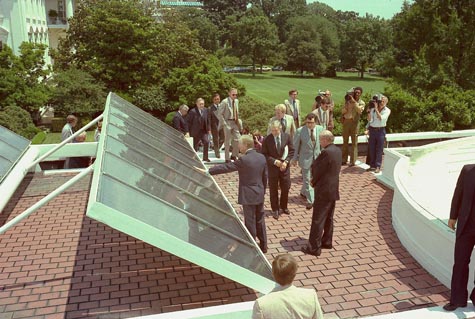

[Image: American President Jimmy Carter dedicates the White House solar panels, 20 June 1979. Photograph © Jimmy Carter Library. Courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture].

[Image: American President Jimmy Carter dedicates the White House solar panels, 20 June 1979. Photograph © Jimmy Carter Library. Courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture].

This is one of the reasons I’ve been talking about climate change, and the possibility of abrupt climate change, as potentially a good thing – in that it forces us to confront problems that we were going to sweep under the carpet for hundreds of years. Now, suddenly, these problems are in our face and we have to deal. And part of dealing is going to be design.

I don’t think people fully comprehend what a gigantic difference their infrastructure makes, or what it feels like to live in a city with public transport, like Paris, compared to one of the big autopias like southern California. The feel of existence is completely different. And of course the carbon burn is also different – and the sense that everybody’s in the same boat together. This partly accounts for the difference between urban voters and rural voters: rural voters – or out-in-the-country voters – can imagine that they’re somehow independent, and that they don’t rely on other people. Meanwhile, their entire tech is built elsewhere. It’s a fantasy, and a bad one as it leads to a false assessment of the real situation.

The Mars books were where I focused on these design questions the most. I had to describe fifteen or twenty invented towns or social structures based around their architecture. Everything from little settlements to crater towns to gigantic cities, to all sorts of individual homes in the outback – how do you occupy the outback? how do you live? – and it was a great pleasure. I think, actually, that one of the main reasons people enjoyed those Mars books was in seeing these alternative design possibilities envisioned and being able to walk around in them, imaginatively.

BLDGBLOG: Were there specific architectural examples, or specific landscapes, that you based your descriptions on?

Robinson: Sure. They had to do with things that I’d seen or read about. And, you know, reading Science News week in and week out, I was always attentive to what the latest in building materials or house design was.

Also, I seized on anything that seemed human-scale and aesthetically pleasing and good for a community. I thought of Greek villages in Crete, and also the spectacular stuff on Santorini. One of the things I learned, wandering around Greek archaeological sites – I’m very interested in archaeology – is that they clearly chose some of their town sites not just for practical concerns but also for aesthetic pleasure. They would put their towns in places where it would look good to live – where you would get a permanent sense that the town was a work of art, as well as a practical solution to economic and geographical problems. That was something I wanted to do on Mars over and over again.

[Image: Photos of Greece, inspiration for life on Mars, taken by Kim Stanley Robinson].

[Image: Photos of Greece, inspiration for life on Mars, taken by Kim Stanley Robinson].

Mondragon, Spain, was also a constant reference point, and Kerala, in southern India. I was looking at cooperative, or leftist, places. Bologna, Italy. The Italian city-states of the Renaissance, in a different kind of way. Also, cities where public transport on a human scale could be kept in mind. That’s mostly northern Europe.

So those were some of the reference points that I remember – but I was also trying to think about how humans might inhabit the unusual Martian features: the cliffsides, the hidden cities that I postulated might be necessary. I was attracted to anything that had to do with circularity, because of the stupendous number of craters on Mars. The Paul Sattelmeier indoor/outdoor house, which is round and easy to build, was something I noticed in Science News as a result of this fixation.

There was a real wide net I could cast there – and it was fun. If you give yourself a whole world to play with, you don’t have to choose just one solution – you can describe any number of solutions – and I think that was politically true as well as architecturally true with my Mars books. They weren’t proposing one master solution, as in the old utopias, but showing that there are a variety of possible solutions, with different advantages and disadvantages.

[Image: A photograph of Santorini taken by Kim Stanley Robinson].

[Image: A photograph of Santorini taken by Kim Stanley Robinson].

BLDGBLOG: Speaking of archaeology, one of the most interesting things I’ve read recently was that some archaeologists are now speculating that sites like the Apollo moon landing, or the final resting spot of the Mars rovers, will someday be like Egypt’s Valley of the Kings: they’ll be excavated and studied and preserved and mapped.

Robinson: Yes, and places like Baikonur, in Kazakhstan, will be quite beautiful. They’ll work as great statuary – like megaliths. They’ll have that charismatic quality and, in their ruin, they should be quite beautiful. As you know, that was one great attraction of the Romantic era – to ruins, to the suggestion of age – and there will be something nicely contradictory about something as futuristic as space artifacts suggesting ruins and the ancient past. That’s sure to come.

The interesting problem on Mars, and Chris McKay has talked about this, is that if we conclude that there’s the possibility of bacterial life on Mars, then it becomes really, really important for us not to contaminate the planet with earthly bacteria. But it’s almost impossible to sterilize a spaceship completely. There were probably 100,000 bacteria even on the sterilized spacecraft that we sent to Mars, living on their inner surfaces. It isn’t even certain that a gigantic crash-landing and explosion would kill all that bacteria.

So Chris McKay has been suggesting that a site like the Beagle or polar lander crash site actually needs to be excavated and fully sterilized – the stuff may even have to be taken off-planet – if we really want to keep Mars uncontaminated. In other words, we’ve contaminated it already; if we find native, alien bacterial life on Mars, and we don’t want it mixed up with Terran life, then we might have to do something a lot more radical than an archaeological saving of the site. We might have to do something like a Superfund clean-up.

Of course, that’s all really hard to do without getting down there with yet more bacteria-infested things.

[Image: Two painted views of a human future on Mars, courtesy of NASA].

[Image: Two painted views of a human future on Mars, courtesy of NASA].

BLDGBLOG: That’s the same situation as with these lakes in Antarctica buried beneath the ice: to study them, we have to drill down into them, but by drilling down into them, we might immediately introduce microbes and bacteria and even chemicals into the water – which will mean that there’s not much left for us to study.

Robinson: They’re already having that problem with Lake Vostok. The Russians have got an ice drill that’s already maybe too close to the lake, and in the sphere of influence of the trapped bacteria. And now people are calculating that the water in Lake Vostok might be very heavily pressurized, and like seltzer water, so that breaking through might cause a gusher on the surface that could last six months. The water might just fly out onto the surface – where it would freeze and create a little mountain up there, of fresh water. Who knows? I mean, at that point, whatever was going on, in bacterial terms, with that lake in particular – that’s ruined. There are many other lakes beneath the Antarctic surface, so it isn’t as if we don’t have more places we could save or study, but that one is already a problem.

[Image: Architecture in Antarctica, photographed by Kim Stanley Robinson].

[Image: Architecture in Antarctica, photographed by Kim Stanley Robinson].

Also, I do like the archaeological sites in Antarctica from the classic era. Those are worth comparing to the space program. Going to Antarctica in 1900 was like us going into space today: as Oliver Morton has put it, it was the hardest thing that technology allowed humans to do at the time. So you could imagine those guys as being in space suits and doing space station-type stuff – but, of course, from our angle, it looks like Boy Scout equipment. It’s amazing that they got away with it at all. Those are the most beautiful spaces – the Shackleton/Scott sites – even the little cairns that Amundsen left behind, or the crashed airplanes from the 1920s: they all become vividly important reminders of our past and of our technological progress. They deserve to be protected fully and kind of revered, almost as religious sites, if you’re a humanist.

[Image: Shackleton’s hut, Antarctica, photographed by Kim Stanley Robinson].

[Image: Shackleton’s hut, Antarctica, photographed by Kim Stanley Robinson].

So archaeology in space? Who knows? It’s hard enough to think about what’s going to go on up there. But on earth it’s very neat to think of Cape Canaveral or Baikonur becoming like Shackleton’s hut.

Thinking along this line causes me to wonder about the Stalinist industrial cities in the Urals – you know, like Chelyabinsk-65. These horribly utilitarian extraction economy-type places, incredibly brutal and destructive – once they’re abandoned, and they begin to rust away, they take on a strange kind of aesthetic. As long as you wouldn’t get actively poisoned when you visit them –

BLDGBLOG: [laughs]

Robinson: – I would be really interested to see some of these places. Just don’t step in the sludge, or scratch your arm – the toxicity levels are supposed to be alarming. But, in archaeological terms, I bet they’d be beautiful.

BLDGBLOG owes a huge and genuine thanks to Kim Stanley Robinson, not only for his ongoing output as a writer but for his patience while this interview was edited and assembled. Thanks, as well, to William L. Fox for putting Robinson and I in touch in the first place.

Meanwhile, the recently published catalog for the exhibition 1973: Sorry, Out of Gas offers a great look at the “big body of utopian design literature that’s now mostly obsolete and out of print” that Robinson mentions in the above interview. If you see a copy, I’d definitely recommend settling in for a long read.

Without Walls: An Interview with Lebbeus Woods

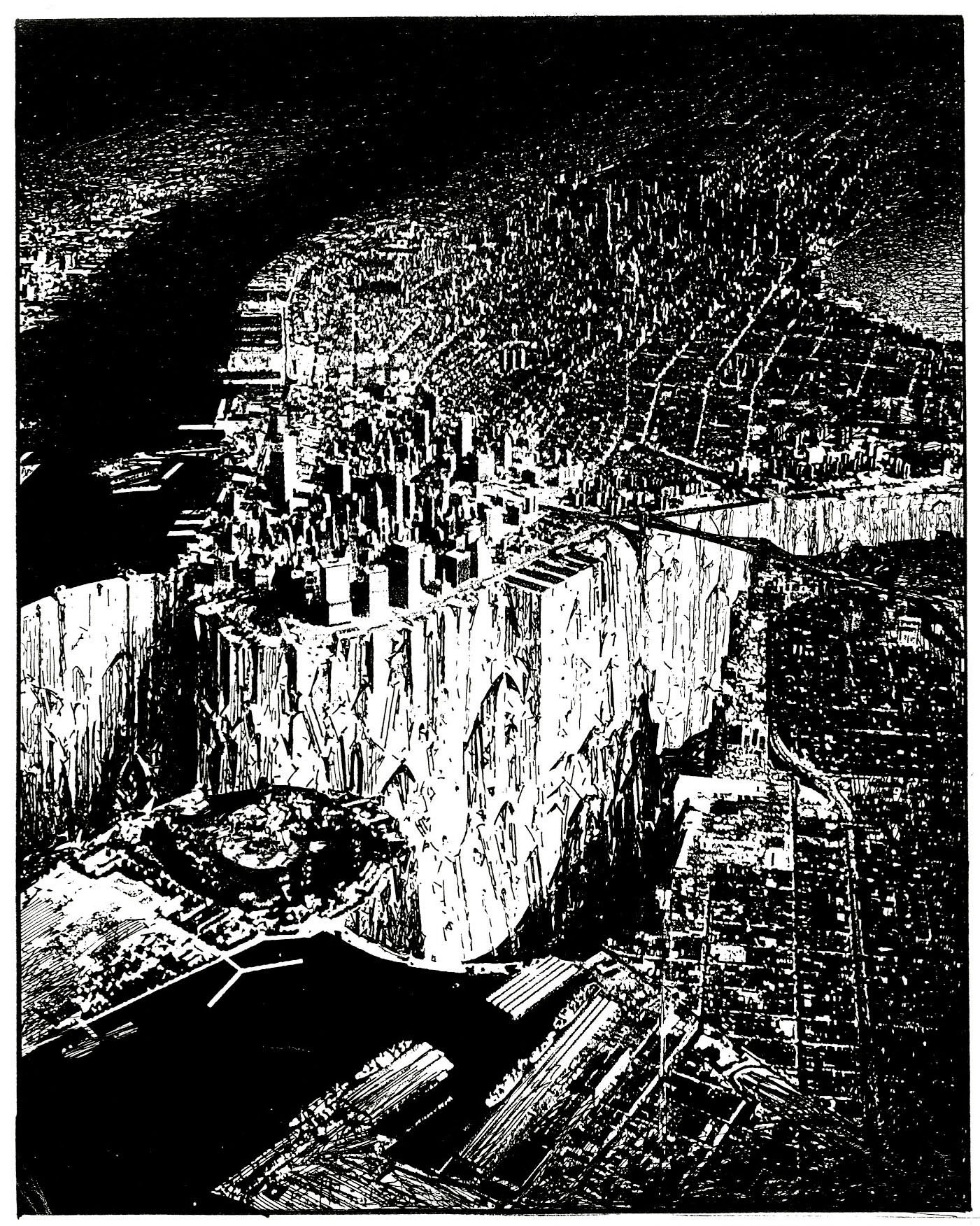

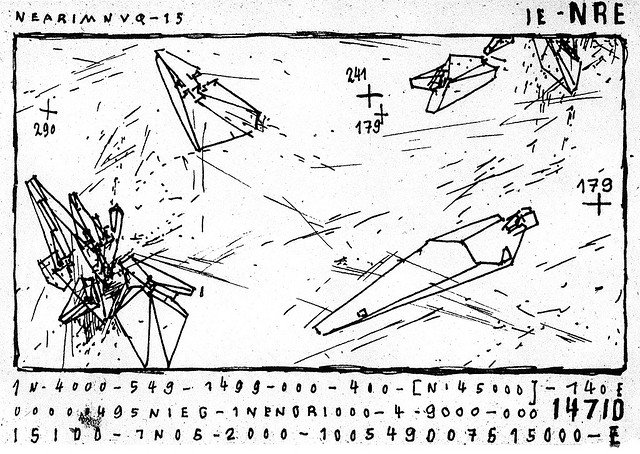

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view larger].

Lebbeus Woods is one of the first architects I knew by name – not Frank Lloyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe, but Lebbeus Woods – and it was Woods’s own technically baroque sketches and models, of buildings that could very well be machines (and vice versa), that gave me an early glimpse of what architecture could really be about.

Woods’s work is the exclamation point at the end of a sentence proclaiming that the architectural imagination, freed from constraints of finance and buildability, should be uncompromising, always. One should imagine entirely new structures, spaces without walls, radically reconstructing the outermost possibilities of the built environment.

If need be, we should re-think the very planet we stand on.

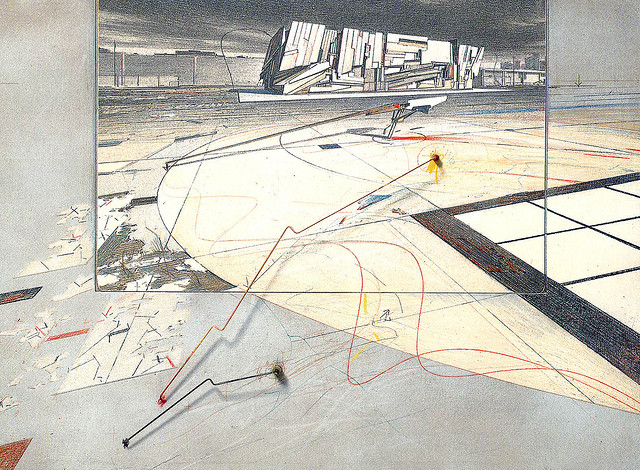

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

Of course, Woods is usually considered the avant-garde of the avant-garde, someone for whom architecture and science fiction – or urban planning and exhilarating, uncontained speculation – are all but one and the same. His work is experimental architecture in its most powerful, and politically provocative, sense.

Genres cross; fiction becomes reflection; archaeology becomes an unpredictable form of projective technology; and even the Earth itself gains an air of the non-terrestrial.

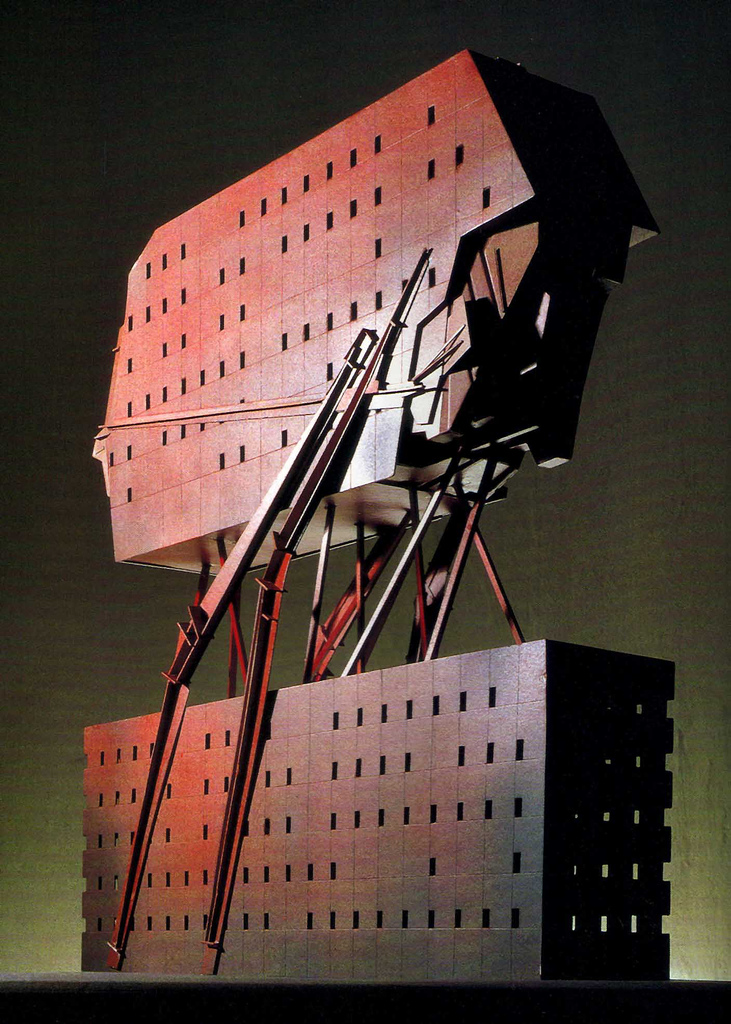

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

One project by Woods, in particular, captured my imagination – and, to this day, it just floors me. I love this thing. In 1980, Woods proposed a tomb for Albert Einstein – the so-called Einstein Tomb (collected here) – inspired by Boullée’s famous Cenotaph for Newton.

But Woods’s proposal wasn’t some paltry gravestone or intricate mausoleum in hewn granite: it was an asymmetrical space station traveling on the gravitational warp and weft of infinite emptiness, passing through clouds of mutational radiation, riding electromagnetic currents into the void.

The Einstein Tomb struck me as such an ingenious solution to an otherwise unremarkable problem – how to build a tomb for an historically titanic mathematician and physicist – that I’ve known who Lebbeus Woods is ever since.

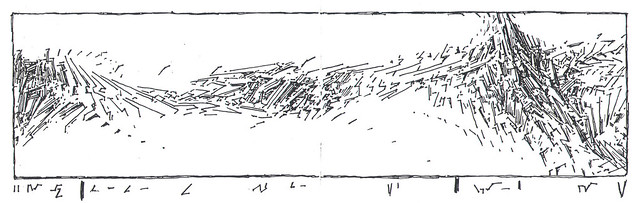

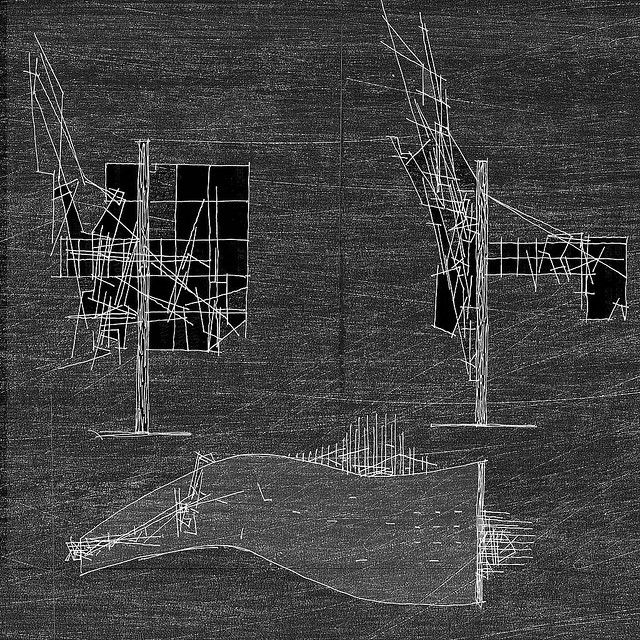

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

So when the opportunity came to talk to Lebbeus about one image that he produced nearly a decade ago, I continued with the questions; the result is this interview, which happily coincides with the launch of Lebbeus’s own website – his first – at lebbeuswoods.net. That site contains projects, writings, studio reports, and some external links, and it’s worth bookmarking for later exploration.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view larger].

In the following Q&A, then, Woods talks to BLDGBLOG about the geology of Manhattan; the reconstruction of urban warzones; politics, walls, and cooperative building projects in the future-perfect tense; and the networked forces of his most recent installations.

• • •

BLDGBLOG: First, could you explain the origins of the Lower Manhattan image?

Lebbeus Woods: This was one of those occasions when I got a request from a magazine – which is very rare. In 1999, Abitare was making a special issue on New York City, and they invited a number of architects – like Steven Holl, Rafael Viñoly, and, oh god, I don’t recall. Todd Williams and Billie Tsien. Michael Sorkin. Myself. They invited us to make some sort of comment about New York. So I wrote a piece – probably 1000 words, 800 words – and I made the drawing.

I think the main thought I had, in speculating on the future of New York, was that, in the past, a lot of discussions had been about New York being the biggest, the greatest, the best – but that all had to do with the size of the city. You know, the size of the skyscrapers, the size of the culture, the population. So I commented in the article about Le Corbusier’s infamous remark that your skyscrapers are too small. Of course, New York dwellers thought he meant, oh, they’re not tall enough – but what he was referring to was that they were too small in their ground plan. His idea of the Radiant City and the Ideal City – this was in the early 30s – was based on very large footprints of buildings, separated by great distances, and, in between the buildings in his vision, were forests, parks, and so forth. But in New York everything was cramped together because the buildings occupied such a limited ground area. So Le Corbusier was totally misunderstood by New Yorkers who thought, oh, our buildings aren’t tall enough – we’ve got to go higher! Of course, he wasn’t interested at all in their height – more in their plan relationship. Remember, he’s the guy who said, the plan is the generator.

So I was speculating on the future of the city and I said, well, obviously, compared to present and future cities, New York is not going to be able to compete in terms of size anymore. It used to be a large city, but now it’s a small city compared with São Paulo, Mexico City, Kuala Lumpur, or almost any Asian city of any size. So I said maybe New York can establish a new kind of scale – and the scale I was interested in was the scale of the city to the Earth, to the planet. I made the drawing as a demonstration of the fact that Manhattan exists, with its towers and skyscrapers, because it sits on a rock – on a granite base. You can put all this weight in a very small area because Manhattan sits on the Earth. Let’s not forget that buildings sit on the Earth.

I wanted to suggest that maybe lower Manhattan – not lower downtown, but lower in the sense of below the city – could form a new relationship with the planet. So, in the drawing, you see that the East River and the Hudson are both dammed. They’re purposefully drained, as it were. The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed, and, in the drawing, there are suggestions of inhabitation in that lower region.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view larger].

So it was a romantic idea – and the drawing is very conceptual in that sense.

But the exposure of the rock base, or the underground condition of the city, completely changes the scale relationship between the city and its environment. It’s peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is. And the new scale relationship is not about huge blockbuster buildings; it’s not about towers and skyscrapers. It’s about the relationship of the relatively small human scratchings on the surface of the earth compared to the earth itself. I think that comes across in the drawing. It’s not geologically correct, I’m sure, but the idea is there.

There are a couple of other interesting features which I’ll just mention. One is that the only bridge I show is the Brooklyn Bridge. I don’t show the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, for instance. That’s just gone. And I don’t show the Manhattan Bridge or the Williamsburg Bridge, which are the other two bridges on the East River. On the Hudson side, it was interesting, because I looked carefully at the drawings – which I based on an aerial photograph of Manhattan, obviously – and the World Trade Center… something’s going on there. Of course, this was in 1999, and I’m not a prophet and I don’t think that I have any particular telepathic or clairvoyant abilities [laughs], but obviously the World Trade Center has been somehow diminished, and there are things floating in the Hudson next to it. I’m not sure exactly what I had in mind – it was already several years ago – except that some kind of transformation was going to happen there.

BLDGBLOG: That’s actually one of the things I like so much about your work: you re-imagine cities and buildings and whole landscapes as if they have undergone some sort of potentially catastrophic transformation – be it a war or an earthquake, etc. – but you don’t respond to those transformations by designing, say, new prefab refugee shelters or more durable tents. You respond with what I’ll call science fiction: a completely new order of things – a new way of organizing and thinking about space. You posit something radically different than what was there before. It’s exciting.

Woods: Well, I think that, for instance, in Sarajevo, I was trying to speculate on how the war could be turned around, into something that people could build the new Sarajevo on. It wasn’t about cleaning up the mess or fixing up the damage; it was more about a transformation in the society and the politics and the economics through architecture. I mean, it was a scenario – and, I suppose, that was the kind of movie aspect to it. It was a “what if?”

I think there’s not enough of that thinking today in relation to cities that have been faced with sudden and dramatic – even violent – transformations, either because of natural or human causes. But we need to be able to speculate, to create these scenarios, and to be useful in a discussion about the next move. No one expects these ideas to be easily implemented. It’s not like a practical plan that you should run out and do. But, certainly, the new scenario gives you a chance to investigate a direction. Of course, being an architect, I’m very interested in the specifics of that direction – you know, not just a verbal description but: this is what it might look like.

So that was the approach in Sarajevo – as well as in this drawing of Lower Manhattan, as I called it.

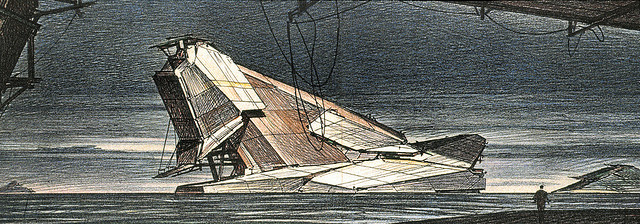

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

BLDGBLOG: Part of that comes from recognizing architecture as its own kind of genre. In other words, architecture has the ability, rivaling literature, to imagine and propose new, alternative routes out of the present moment. So architecture isn’t just buildings, it’s a system of entirely re-imagining the world through new plans and scenarios.

Woods: Well, let me just back up and say that architecture is a multi-disciplinary field, by definition. But, as a multi-disciplinary field, our ideas have to be comprehensive; we can’t just say: “I’ve got a new type of column that I think will be great for the future of architecture.”

BLDGBLOG: [laughs]

Woods: Maybe it will be great – but it’s not enough. I think architects – at least those inclined to understand the multi-disciplinarity and the comprehensive nature of their field – have to visualize something that embraces all these political, economic, and social changes. As well as the technological. As well as the spatial.

But we’re living in a very odd time for the field. There’s a kind of lack of discourse about these larger issues. People are hunkered down, looking for jobs, trying to get a building. It’s a low point. I don’t think it will stay that way. I don’t think that architects themselves will allow that. After all, it’s architects who create the field of architecture; it’s not society, it’s not clients, it’s not governments. I mean, we architects are the ones who define what the field is about, right?

So if there’s a dearth of that kind of thinking at the moment, it’s because architects have retreated – and I’m sure a coming generation is going to say: hey, this retreat is not good. We’ve got to imagine more broadly. We have to have a more comprehensive vision of what the future is.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

BLDGBLOG: In your own work – and I’m thinking here of the Korean DMZ project or the Israeli wall-game – this “more comprehensive vision” of the future also involves rethinking political structures. Engaging in society not just spatially, but politically. Many of the buildings that you’ve proposed are more than just buildings, in other words; they’re actually new forms of political organization.

Woods: Yeah. I mean, obviously, the making of buildings is a huge investment of resources of various kinds. Financial, as well as material, and intellectual, and emotional resources of a whole group of people get involved in a particular building project. And any time you get a group, you’re talking about politics. To me politics means one thing: How do you change your situation? What is the mechanism by which you change your life? That’s politics. That’s the political question. It’s about negotiation, or it’s about revolution, or it’s about terrorism, or it’s about careful step-by-step planning – all of this is political in nature. It’s about how people, when they get together, agree to change their situation.

As I wrote some years back, architecture is a political act, by nature. It has to do with the relationships between people and how they decide to change their conditions of living. And architecture is a prime instrument of making that change – because it has to do with building the environment they live in, and the relationships that exist in that environment.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

BLDGBLOG: There’s also the incredibly interesting possibility that a building project, once complete, will actually change the society that built it. It’s the idea that a building – a work of architecture – could directly catalyze a transformation, so that the society that finishes building something is not the same society that set out to build it in the first place. The building changes them.

Woods: I love that. I love the way you put it, and I totally agree with it. I think, you know, architecture should not just be something that follows up on events but be a leader of events. That’s what you’re saying: That by implementing an architectural action, you actually are making a transformation in the social fabric and in the political fabric. Architecture becomes an instigator; it becomes an initiator.

That, of course, is what I’ve always promoted – but it’s the most difficult thing for people to do. Architects say: well, it’s my client, they won’t let me do this. Or: I have to do what my client wants. That’s why I don’t have any clients! [laughter] It’s true.

Because at least I can put the ideas out there and somehow it might seep through, or filter through, to another level.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

BLDGBLOG: Finally, it seems like a lot of the work you’ve been doing for the past few years – in Vienna, especially – has been a kind of architecture without walls. It’s almost pure space. In other words, instead of walls and floors and recognizable structures, you’ve been producing networks and forces and tangles and clusters – an abstract space of energy and directions. Is that an accurate way of looking at your recent work – and, if so, is this a purely aesthetic exploration, or is this architecture without walls meant to symbolize or communicate a larger political message?

Woods: Well, look – if you go back through my projects over the years, probably the least present aspect is the idea of property lines. There are certainly boundaries – spatial boundaries – because, without them, you can’t create space. But the idea of fencing off, or of compartmentalizing – or the capitalist ideal of private property – has been absent from my work over the last few years.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

I think in my more recent work, certainly, there are still boundaries. There are still edges. But they are much more porous, and the property lines… [laughs] are even less, should we say, defined or desired.

So the more recent work – like in Vienna, as you mentioned – is harder for people to grasp. Back in the early 90s I was confronting particular situations, and I was doing it in a kind of scenario way. I made realistic-looking drawings of places – of situations – but now I’ve moved into a purely architectonic mode. I think people probably scratch their heads a little bit and say: well, what is this? But I’m glad you grasp it – and I hope my comments clarify at least my aspirations.

Probably the political implication of that is something about being open – encouraging what I call the lateral movement and not the vertical movement of politics. It’s the definition of a space through a set of approximations or a set of vibrations or a set of energy fluctuations – and that has everything to do with living in the present.

All of those lines are in flux. They’re in movement, as we ourselves develop and change.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

• • •

BLDGBLOG owes a huge thanks to Lebbeus Woods, not only for having this conversation but for proving over and over again that architecture can and should always be a form of radical reconstruction, unafraid to take on buildings, cities, worlds – whole planets.

For more images, meanwhile, including much larger versions of all the ones that appear here, don’t miss BLDGBLOG’s Lebbeus Woods Flickr set. Also consider stopping by Subtopia for an enthusiastic recap of Lebbeus’s appearance at Postopolis! last Spring; and by City of Sound for Dan Hill’s synopsis of the same event.

The Elephants of Rome: An Interview with Mary Beard (pt. 2)

This is Part Two of a two-part interview with Mary Beard, Professor of Classics at Cambridge University and general editor of the Wonders of the World, a new series published by Profile and Harvard University Press.

Part One can be found here.

In this installment we discuss cultural authenticity and the rise of archaeo-tourism; China, the pirating of ancient history, and plaster casts of statuary; A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum; the little-understood lost lifestyle patterns of the pyroclastically entombed Pompeii; and the urban military spectacles of imperial Rome.

In this installment we discuss cultural authenticity and the rise of archaeo-tourism; China, the pirating of ancient history, and plaster casts of statuary; A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum; the little-understood lost lifestyle patterns of the pyroclastically entombed Pompeii; and the urban military spectacles of imperial Rome.

BLDGBLOG: I’d like to ask you about different cultural attitudes toward copying and historical reproduction. There’s an essay by Alexander Stille, for instance, called “The Culture of the Copy and the Disappearance of China’s Past,” where he describes how meticulous copies are often used in China as stand-ins for ancient artifacts – without that substitution being acknowledged. Stille writes that, in China, copying “is a sign of reverence rather than lack of originality.” Do you foresee any sort of interpretive conflict on the horizon between these different cultural notions of authenticity and the past?

Mary Beard: This idea, of the meticulous copy being used as a stand-in for the ancient artifact – and that, somehow, this substitution can be its own historical object – well that’s one we actually find our own past. It’s not just a Chinese thing.

I’ve been thinking recently about the role of the plaster cast, and about collections of plaster casts; and, in a sense, it seems to me that the cult of the plaster cast, in seventeenth to early mid-nineteenth century Europe, had much in common with what Stille’s describing in China. Now – and I mean since the total commitment within modernism to “authenticity” – we regard plaster casts as cheap and perhaps awkward copies of the original. But, certainly, in the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, plaster casts were the object that provided people with “real” connection with the classical world. The plaster cast was, in a sense, the fount of classical art and classical knowledge, and people like Goethe were inspired not so much by what we would think of as the authentic marble object, but by looking at plaster casts.

At one point in the Parthenon book – I mention it just very briefly – there was a moment, in the 1930s, when the British Museum had got all of Elgin’s marbles there, but the bits they didn’t have they filled in with plaster casts from Greece. It wasn’t that the casts were actually valued the same, but that viewers could happily see these things, side by side, in order to experience the Parthenon sculptures.

I think it’s actually quite moving sometimes, reading people’s accounts of Greek and Roman sculpture in the eighteenth and nineteenth century – because they’re describing plaster casts using a language which we would not now use for copies. They’re not framing it as a copy – they’re framing it as if it was it – or at least as if was sufficiently like the “real thing” to be able to prompt some of the same language and emotions.

[Image: A view of the Elgin Marbles, via the Wik].

[Image: A view of the Elgin Marbles, via the Wik].

BLDGBLOG: That seems to be as much about the desire to encounter the thing itself as to use convenient stand-ins for that thing, when “authenticity” is simply too expensive to afford.

Mary Beard: That’s partly it – but one thing that’s curious is that the modern city of Rome produced and displayed loads of plaster casts until quite recently (and there is still a great collection in the University gallery in Rome). They went in for making plaster casts of sculpture when they’d got the real stuff sitting right there in front of them. “Authenticity” is always a trickier idea than we think it is – which is, I guess, one of the things that “post-modernism” has been about telling us.

BLDGBLOG: Do you see educational value in things like merchandising, then? Do souvenirs obscure the past or give people access to it?

Mary Beard: I tend to be pretty laid back about it. I mean, I can do the argument about commodification if you like. I can say: goodness me, what you are doing? You’re re-presenting a tawdry cheap object, to make a vast amount of profit, and it’ll be bought by somebody else in the belief that, somehow, they have just bought into cultural property. I can do the gloomy side of it.

But I think it also goes back, more positively, to the idea that these objects are sort of shared. How do you share a monument? One of the main ways that you share a monument is by replicating it and letting people own the replica. It’s a way that people can feel they have a relationship to the original. That’s been going on since antiquity itself. One of the things that’s quite extraordinary is the number of relatively small-scale replicas there are of the cult statue of Athena from the Parthenon – hundreds of them.

Of course, in some ways, you say, tourists are being palmed off with plastic souvenirs instead of with knowledge – and, of course, some of these things, the middle class cultural critics can say, are horrible and cheap, and people think they’re buying culture when, in fact, they’re buying a nasty little replica. Obviously there’s an ambivalence there, but it never seems to me to be wholly bad.

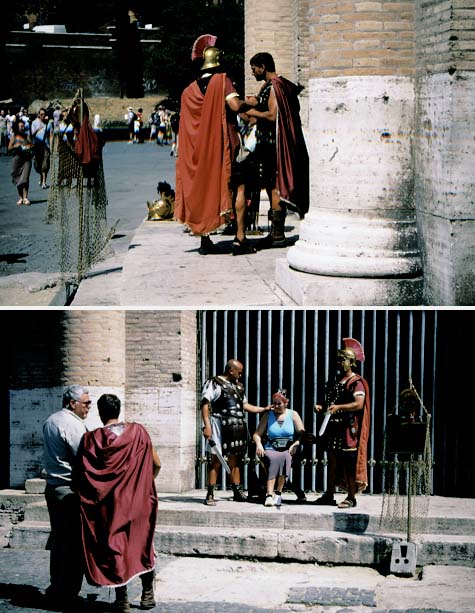

You know, you have your photograph taken at the Colosseum next to somebody dressed up like a gladiator. Is that a terrible bit of exploitation because you’ve just paid a ridiculous amount of money? Well, that’s exactly what it is in one way – but it’s also a way of writing yourself into the history of that site, and saying “I was there.”

[Images: Tourists having their picture taken “next to somebody dressed up like a gladiator.” Photo by Robin Cormack].

[Images: Tourists having their picture taken “next to somebody dressed up like a gladiator.” Photo by Robin Cormack].

BLDGBLOG: For a lot of people, there’s also a sense of irony there – in the idea that you’d get your picture taken next to a gladiator. It’s like a joke: look at me, wearing shorts, standing next to an Italian guy dressed like a gladiator.

Mary Beard: Yes, that’s right. I don’t think one’s capacity for self-ironization is necessarily incompatible with the idea of ownership. When I buy my ouzo bottle shaped like the Parthenon, it’s another way to the same end.

We tend to think that tourists are dupes being flogged crap which they don’t realize is crap. Actually, I suspect that most people, like you and I, do realize that it’s crap. The point is to buy crap, because that’s part of what the deal is – that’s the transaction which you’re doing.

I suppose it’s all part of what I’m thinking in general: people are much smarter about their engagement with these places than we often give them credit for. They/we have quite a highly developed sense of what the touristic game is all about. I might be an expert when it comes to the Parthenon, but I go to hundreds of places where I know nothing at all – but I still know what the contract is, between the tourist and the monument.

[Images: The streets of Pompeii, via Wikipedia].

[Images: The streets of Pompeii, via Wikipedia].

BLDGBLOG: This changes the subject a bit, but I understand you’re also writing a new book about Pompeii. Is that for the Wonders for the World?

Mary Beard: I am writing a Pompeii book, and it’s for Profile and Harvard, like the Wonders. However, it’s not in the series because it’s going to be rather longer than that – and there’s a practical consideration here. If you’re going to tell your authors not to do more than 50,000 words, then you can’t have the series editor deciding she wants to do 100,000 words!

I suppose I’m trying to do some quite specific things. I’ve worked on and off on Pompeii for 20 or 30 years, and it struck me that, apart from the study of volcanology (where everybody will talk till the cows come home about “pyroclastic flows” and all that), by and large there’s an increasing gap between what academic studies of Pompeii are doing and the kind of stuff that popular books on Pompeii feed people. I wanted to see if I could close a bit of that gap between what people normally get given, if they’re not specialists, and some of the ways of thinking about the city that are current within academic debate.