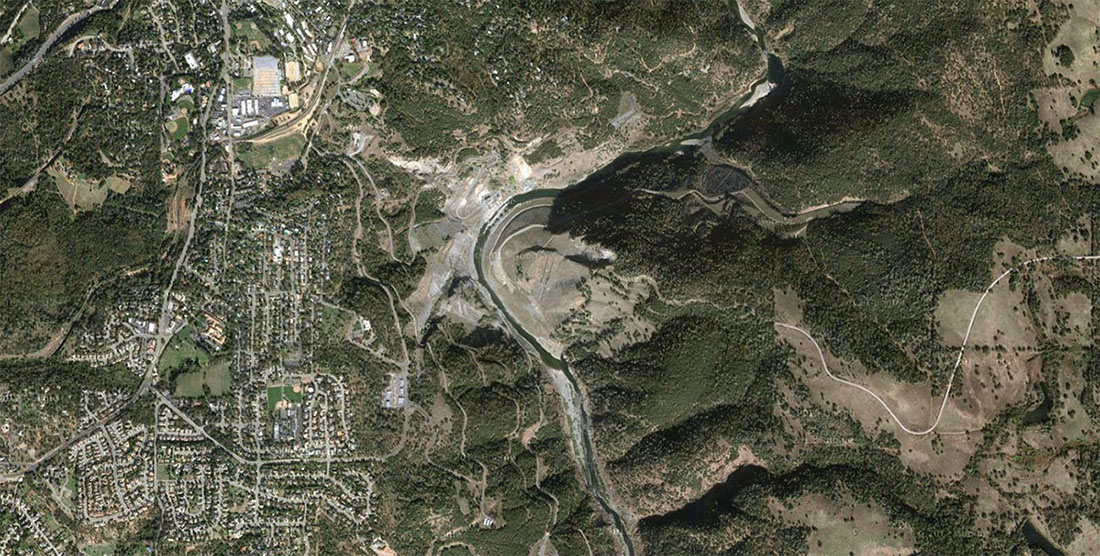

[Image: The Auburn Dam site, via Google Maps].

[Image: The Auburn Dam site, via Google Maps].

While re-reading John McPhee’s excellent book Assembling California last month for the San Andreas Fault National Park studio, I was struck once again by a short description of a Californian landscape partially redesigned in preparation for a reservoir that never arrived.

McPhee is referring to the Auburn Dam, in the city of Auburn, northeast of Sacramento (and near a small town called, of all things, Cool, California). The $1 billion Auburn Dam would have been “the largest concrete arched dam in the world,” according to Geoengineer.org, but construction was abandoned over fears that seismic activity might cause the dam to collapse, inundating Sacramento.

Construction was begun, however, and its cessation produced some rather unassuming ruins—basically large piles of exposed gravel and rock now eroding in springtime floods.

Nonetheless, these mounds were not cheap, including “$327 million concrete abutments [that] stand in stark contrast to the rest of the oak-filled canyon,” as the Auburn-Cool Trail site (or ACT) explains. “The washout of the 250-foot coffer dam in 1986 left huge scars that continue to erode, with large broken pipes sticking out in a precarious manner. Hasty roadbuilding for the project has contributed to landslides that have caused sedimentation and increased turbidity in the river downstream and in Folsom Lake. The cost of seasonal repairs on the service roads alone has run into the millions of dollars, and many roads remain cracked and unsafe.”

[Image: A bypass tunnel built in anticipation of the never-completed Auburn Dam; photo by D.P. Zeccos of Geoengineer.org].

[Image: A bypass tunnel built in anticipation of the never-completed Auburn Dam; photo by D.P. Zeccos of Geoengineer.org].

Amazingly, though, and this is where we come to John McPhee, regional infrastructure was constructed with an eye on what the landscape would look like in the future, given the presence of the Auburn Dam, leading to surreal sights like the Foresthill Bridge.

The bridge, which you can still drive on today, is a towering structure remarkably out of proportion with the landscape, its unnecessary height all but incomprehensible until you imagine the cold waters of the American River rising up behind the Auburn Dam, forming a recreational lake and reservoir, the lights of the bridge reflected at night in the waters below. “Not particularly long,” McPhee quips, “the bridge was built so high in order to clear the lake that wasn’t there.”

[Image: The Foresthill Bridge, via Wikipedia].

[Image: The Foresthill Bridge, via Wikipedia].

Weirdest of all, McPhee writes, there were boat docks built high up on the surrounding hillsides, waiting for their lake.

One gravel boat ramp, he explains, “several hundred yards long, descends a steep slope and ends high and nowhere, a dangling cul-de-sac. The skeletons [a skeleton crew of federal workers stationed at the former dam site] call it ‘the largest and highest unused boat ramp in California.’ Houses that cling to the canyon sides look into the empty pit. They were built around the future lakeshore under the promise of rising water. You can almost see their boat docks projecting into the air. Thirty-three hundred quarter-acre lots were platted in a subdivision called Auburn Lake Trails.”

[Image: The expected waters of a lake that never arrived; via Wikipedia].

[Image: The expected waters of a lake that never arrived; via Wikipedia].

While I will confess that, while using the omniscient eye of Google Maps, I can’t find these gravel boat ramps leading down to the rim of a lake that doesn’t exist—looking in vain for a maze of quasi-lakeside home lots perched uselessly in the hills—I assume that it’s either because the ramps have long since revegetated, given the two decades that have passed since the publication of McPhee’s book, or perhaps because there was a certain amount of willful projection on McPhee’s part in the first place.

After all, the idea of a line of homes built far up in the hills somewhere, overlooking an empty space in which a lake should be, is so beautiful, and so perfectly odd, that it would be tempting to conjure it into being, imagining bored kids in a town called Cool riding their bikes down to lost docks in the woods each summer near sunset, climbing over maritime ruins slowly crumbling in the mountains, throwing rocks at rotting lifejackets, building small forts inside the discarded hulls of someone else’s midlife crisis, perhaps still waiting, even hoping, for a flood to come.

As always, interesting!

However, such landscapes built in advance do exist in the recultivation of mining areas, like this one near Leipzig (Germany) on Zwenkau Lake (http://goo.gl/maps/5e3rx)

Activate "photos" and get an idea of how absurd this is.

The port and also some housing have already been built long before the water arrives. The water is today already there, but a few years ago it was quite disturbing to see the port "hanging" up there on the naked slope. To make the experience perfect, already in the beginning of the flooding process, you could go on a boat trip on the slowly rising lake, seeing the whole scenery of a complete port far above the actual waterline from a very unusual angle!

For an update on life at the Auburn Dam site since John McPhee wrote about it twenty-plus years ago, Jordan Fisher Smith's Nature Noir (http://www.naturenoir.com/) is excellent. Smith was a USFS park ranger at the site, a place that, due to the dam that was never finished, existed as a lawless zone where the norm was shifted far off 'civilized' expectations. Smith is a great writer, combining McPhee with Gary Snyder with the dystopian vision of Mike Davis, all of whom are cited in the book itself.

I really love the idea of speculative design, particularly in the context of the San Andreas studio.

It wouldn't surprise me too much, however, if McPhee was willfully projecting, as you put it. In the first chapter of the same book, at the end of the evocative allegory of the antique-filled loft, McPhee produces the almost certainly fictional, or at the very least ungoogleably obscure, reference to "a temple bell dating to Auspicion Day of the fifth month of the first year of Tembrun."

Or perhaps the omniscience of Google has a property we can call "the McPhee Limit"?

Thanks for the comments! Michael, Alan, thanks for the links, as well. The Smith book sounds terrific.

Wileycount, the "McPhee Limit" is a pretty great proposition—that which remains ungoogleable—however, in that specific case, it seems he's deliberately just listing a whole bunch of random stuff (pieces of furniture, antiques, historical objects, etc.) to illustrate a geological point. Nonetheless, point taken! McPhee is a great example of what we might call speculative nonfiction.

I had to re-format a comment from jenkesler (simply because of Blogger's idiotic limitations); the original comment, with new formatting, reads as follows:

I was so pleasantly surprised to see this story! I, in fact, live in Cool California in Auburn Lake Trails. I have hiked down to the dam remnants and imagined what the landscape would be had the dam been built. Imagined if I would have been able to walk to the lake from my home, etc. This is a map of the (huge) neighborhood that is ALT in case you were still wondering.

The dam construction also created a wonderful road that leads from highway 49 down to the dam site. It is a great place to go running as there are no cars allowed. It is also where I got married last summer.

***

[Jen, congrats on the wedding!]

Geoff–to perhaps further entice you to read Nature Noir I've posted a review of the book I wrote a few years ago at my blog Everyday Structures: http://www.everydaystructures.com/2013/03/reading-condemned-landscape-nature-noir.html

Thanks for getting me thinking about the Sierra foothills – doing so is a great way to forget about how winter is lingering in the Northeast.

Very interesting and perfectly timed. I was just up in that area this past weekend. At one point I noted several homes high on the hillside and thought it odd how they were located. Now I know why.

The crumbling ramps to nowhere reminds me of a plot point in Kim Stanley Robinson's 2132, where two competing cities are being built on a mountainside in expectation of a terraformed sea-to-be. Both are built with docks and other oceanside touches, despite being hundreds of metres apart in elevation. The developers, meanwhile, work to manipulate the terraforming efforts to bring the water to their doorstep.

Not that political/real estate maneuvering in massive landscaping projects is all that novel or science fictional. The developers of the boat ramps to nowhere would have put some mighty efforts into keeping the project going, I imagine.

The Foresthill Bridge is still the 4th highest (road level to river level) bridge in the U.S., and may still be in the top 20 worldwide. There is a seismic retrofit in progress, which gave me the opportunity to shoot a few pictures *from* the bridge; they're here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/danceslut/sets/72157626037207709/

Adam, you might like BLDGBLOG's old interview with Kim Stanley Robinson, if you haven't seen it.

Anthony, great to see those shots! Thanks.