The blog Landscapism takes a look at the “integral but largely uncharted topography” of the combe, the “amphitheatre-like landform that can be found at the head of a valley.” There, the post’s author writes, amidst lichen-covered rubble and interrupted creeks, “these watery starting lines disguised as cul-de-sacs are a gift to the rural flâneur; sheep tracks, streams, crags, ruined sheep folds—all encourage the curious visitor to roam hither and thither rather than plod a linear course.”

Tag: England

Howl

I watched this video with the typical ennui of your average internet user—expecting to hear nothing at all, really, before going back to other forms of online procrastination—but holy Hannah. This is a pretty loud building.

Although I would be making surreptitious ambient field recordings—and rhapsodizing to my sleepless friends about the unrealized acoustic dimensions of contemporary architecture—I have to say I’d be pretty unenthused to have this thing howling all day, everyday, in my neighborhood.

It’s Manchester’s Beetham Tower. It cost £150 million to build, and its accidental sounds are apparently now “the stuff of legend.”

(Spotted via Justin Davidson. This actually reminds me of when my housemate in college taught himself to play the saw and I had no idea what was happening).

Subterranean Saxophony

[Image: Photo by Steve Stills, courtesy of the Guardian].

[Image: Photo by Steve Stills, courtesy of the Guardian].

Over in London later today, the Guardian explains, composer Iain Chambers will premiere a new piece of music written for an unusual urban venue: “the caverns that contain the counterweights of [London’s Tower Bridge] when it’s raised.”

The space itself has “the acoustics of a small cathedral,” Sinclair told the newspaper, citing John Cage as an influence and urging readers “to listen to environmental sounds and treat them as music,” whether it’s the rumble of a bridge being raised or the sounds of boats on the river.

In fact, Chambers will be performing one of Cage’s pieces during the show tonight—but, alas, I suspect it is not this one:

It is rumored that the final, dying words of composer John Cage were: “Make sure they play my London piece… You have to hear my London piece…” He was referring, many now believe, to a piece written for the subterranean saxophony of London’s sewers.

Read much more at the Guardian—or, even better, stop by tonight for a live performance.

(Spotted via @nicolatwilley).

Bunker Simulations

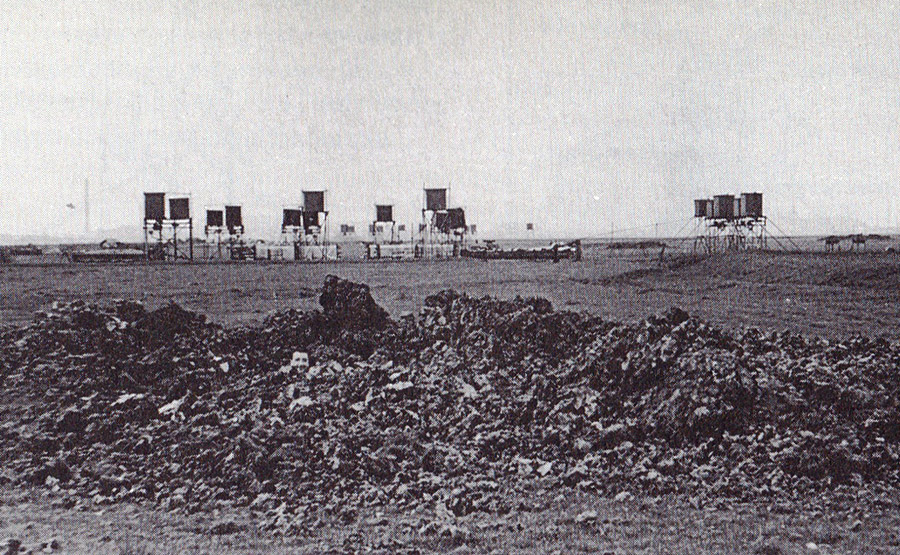

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

The continent-spanning line of concrete bunkers built by the Nazis during WWII, known as the “Atlantic Wall,” was partially recreated in the United Kingdom—in more than one location—to assist with military training.

These simulated Nazi bunkers now survive as largely overlooked ruins amidst the fields, disquieting yet picturesque earth forms covered in plants and lichen, their internal rebar exposed to the weather and twisted by explosives, serving as quiet reminders of the European battlefield.

The various wall sites even include trenches, anti-tank ditches, and other defensive works carved into the ground, forming a kind of landscape garden of simulated fortification.

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

As the Herald Scotland reported the other day, one of these walls “was built at Sheriffmuir, in the hills above Dunblane, in 1943 as preparations were being made to invade Europe. The problem was the Nazis had built a formidable line of concrete defenses from Norway all the way to the Spanish border and if D-Day was to have any chance of success, the British and their allies would have to get over those defenses.”

This, of course, “is why the wall at Sheriffmuir was built: it was a way for the British forces to practise their plan of attack and understand what they would face. They shot at it, they smashed into it, and they blew it up as a way of testing the German defences ahead of D-Day.”

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

It would certainly be difficult to guess what these structures are at first glance, or why such behemoth constructions would have been built in these locations; stumbling upon them with no knowledge of their history would suggest some dark alternative history of WWII in which the Nazis had managed to at least partially conquer Britain, leaving behind these half-buried fortresses in their wake.

Indeed, the history of the walls remains relatively under-exposed, even in Britain, and a new archaeological effort to scan all of the defenses and mount an exhibition about them in the Dunblane Museum is thus now underway.

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via Stirling 2014].

The story of the Scottish wall’s construction is also intriguingly odd. It revolves around an act of artistic espionage, courtesy of “a French painter and decorator called Rene Duchez.”

Duchez, the newspaper explains, “got his hands on the blueprints for the German defences while painting the offices of engineering group TODT, which [had been hired] to build the Atlantic walls. He hid the plans in a biscuit tin, which was smuggled to Britain and used as the blueprint for the wall at Sheriffmuir.”

But Scotland is not the only UK site of a simulated Nazi super-wall: there were also ersatz bunkers built in Surrey, Wales, and Suffolk. In fact, the one in Surrey, built on Hankley Common, is not all that far from my in-laws, so I’ll try to check it out in person next time I’m over in England.

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by Shazz, bottom three photos via Wikipedia].

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by Shazz, bottom three photos via Wikipedia].

Attempts at archaeological preservation aside, these walls seem destined to fade into the landscape for the next several millennia, absorbed back into the forests and fields; along the way, they’ll join other ancient features like Hadrian’s Wall on the itinerary of future military history buffs, just another site to visit on a slow Sunday stroll, their original context all but forgotten.

(Spotted via Archaeology. Previously on BLDGBLOG: In the Box: A Tour Through The Simulated Battlefields of the U.S. National Training Center and Model Landscape].

The Peterborough Tunnels

A weird old story I came across in my bookmarks this morning tells a tale of tunnels under the town of Peterborough, England.

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of Peterborough Today].

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of Peterborough Today].

The local newspaper, Peterborough Today, refers to a woman described simply as “a grandmother” who claims “that she crawled through a tunnel under Peterborough Cathedral as a schoolgirl.” That experience—organized as a school trip, of all things—was “terrifying”; in fact, it was “so scary that it gave her nightmares for weeks afterwards.”

About 25 of us went down into the tunnel, one at a time; none of the teachers came in. It was pitch black, had a stone floor and was about two feet high and three feet wide. We crawled along on our hands on knees. The girl in front of me stopped and started screaming, she was so scared. The tunnel started in the Cathedral and ended there too; we were down there for what seemed like ages. When I eventually got home I was in tears. Afterwards I had horrible nightmares for weeks about being buried alive underneath the Cathedral.

What’s fascinating about the story, though, is the fact that not everyone even agrees that these tunnels exist. A “city historian” quoted in the same article says that, while “there are small tunnels under the Cathedral,” they are most likely not tunnels at all, but simply “the ruins of foundations from earlier churches on the site, dating from Saxon times.” The girls would thus have been crawling around amongst the foundations of ruined churches, lost buildings that long predated the cathedral above them.

But local legends insist that the tunnels—or, perhaps, just one very large tunnel—might, in fact, be real. To this end, an amateur archaeologist named Jay Beecher, who works in a local bank by day, has “been intrigued by the legend of the tunnel ever since he was a young boy when he was regaled with tales that had been passed down the generations of a mysterious passageway under the city.” This “mysterious passageway under the city” would be nearly 800 years old, by his reckoning, and more than a mile in length. “Medieval monks may have used the tunnel as a safe route to visit a sacred spring at Holywell to bathe in its healing waters,” we read.

Although Beecher has found indications of the tunnel on city maps, not everyone is convinced, claiming the whole thing is just “folklore.” But it is oddly ubiquitous folklore. One former resident of town who contacted the newspaper “claimed that a series of tunnels ran between Peterborough and Thorney via a secret underground chapel.” Another “said that he recalled seeing part of a tunnel in the cellar at a home in Norfolk Street, Peterborough,” as if the tunnel flashes in and out of existence around town, from basement to basement, church cellar to pub storage room, more a portal or instance gate than an actual part of the built environment. And then, of course, there is the surreal childhood memory—or nightmare—recounted by the “grandmother” quoted above who once crawled beneath the town church with 25 of her schoolmates, worried that they’d all be buried alive in the center of town (surely the narrative premise of a childhood anxiety dream if there ever was one).

No word yet if Beecher has found his archaeological evidence, but the fact that this particular spatial feature makes an appearance in the dreams, memories, or confused geographic fantasies of the people who live there—as if their town can only be complete given this subterranean underside, a buried twin lost beneath churches—is in and of itself remarkable.

(If this interests you—or even if it doesn’t—take a quick look at BLDGBLOG’s tour through the tunnels and sand mines of Nottingham, or stop by this older post on the “undiscovered bedrooms of Manhattan“).

Starfish City

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of Archigram, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of Archigram, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

A few other things that will probably come up this evening at the Architectural Association, in the context of the British Exploratory Land Archive project, are the so-called “Starfish sites” of World War II Britain. Starfish sites “were large-scale night-time decoys created during The Blitz to simulate burning British cities.”

[Image: A Starfish site burning, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

[Image: A Starfish site burning, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

Their nickname, “Starfish,” comes from the initials they were given by their designer, Colonel John Turner, for “Special Fire” sites or “SF.”

As English Heritage explains, in their list of “airfield bombing decoys,” these misleading proto-cities were “operated by lighting a series of controlled fires during an air raid to replicate an urban area targeted by bombs.” They would thus be set ablaze to lead German pilots further astray, as the bombers would, at least in theory, fly several miles off-course to obliterate nothing but empty fields camouflaged as urban cores.

They were like optical distant cousins of the camouflaged factories of Southern California during World War II.

Being in a hotel without my books, and thus relying entirely on the infallible historical resource of Wikipedia for the following quotation, the Starfish sites “consisted of elaborate light arrays and fires, controlled from a nearby bunker, laid out to simulate a fire-bombed town. By the end of the war there were 237 decoys protecting 81 towns and cities around the country.”

[Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the St. Margaret’s Community Website].

[Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the St. Margaret’s Community Website].

The specific system of visual camouflage used at the sites consisted of various special effects, including “fire baskets,” “glow boxes,” reflecting pools, and long trenches that could be set alight in a controlled sequence so as to replicate the streets and buildings of particular towns—1:1 urban models built almost entirely with light.

In fact, in some cases, these dissimulating light shows for visiting Germans were subtractively augmented, we might say, with entire lakes being “drained during the war to prevent them being used as navigational aids by enemy aircraft.”

Operational “instructions” for turning on—that is, setting ablaze—”Minor Starfish sites” can be read, courtesy of the Arborfield Local History Society, where we also learn how such sites were meant to be decommissioned after the war. Disconcertingly, despite the presence of literally tons of “explosive boiling oil” and other highly flammable liquid fuel, often simply lying about in open trenches, we read that “sites should be de-requisitioned and cleared of obstructions quickly in order to hand the land back to agriculture etc., as soon as possible.”

The remarkable photos posted here—depicting a kind of pyromaniac’s version of Archigram, a temporary circus of flame bolted together from scaffolding—come from the St. Margaret’s Community Website, where a bit more information is available.

In any case, if you’re around London this evening, Starfish sites, aerial archaeology, and many other noteworthy features of the British landscape will be mentioned—albeit in passing—during our lecture at the Architectural Association. Stop by if you’re in the neighborhood…

(Thanks to Laura Allen for first pointing me to Starfish sites).

Caves of Nottingham

[Image: Cliffs and caves of Nottingham; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: Cliffs and caves of Nottingham; photo by Nicola Twilley].

For several years now, I’ve admired from afar the ambitious laser-scanning subterranean archaeological project of the Nottingham Caves Survey.

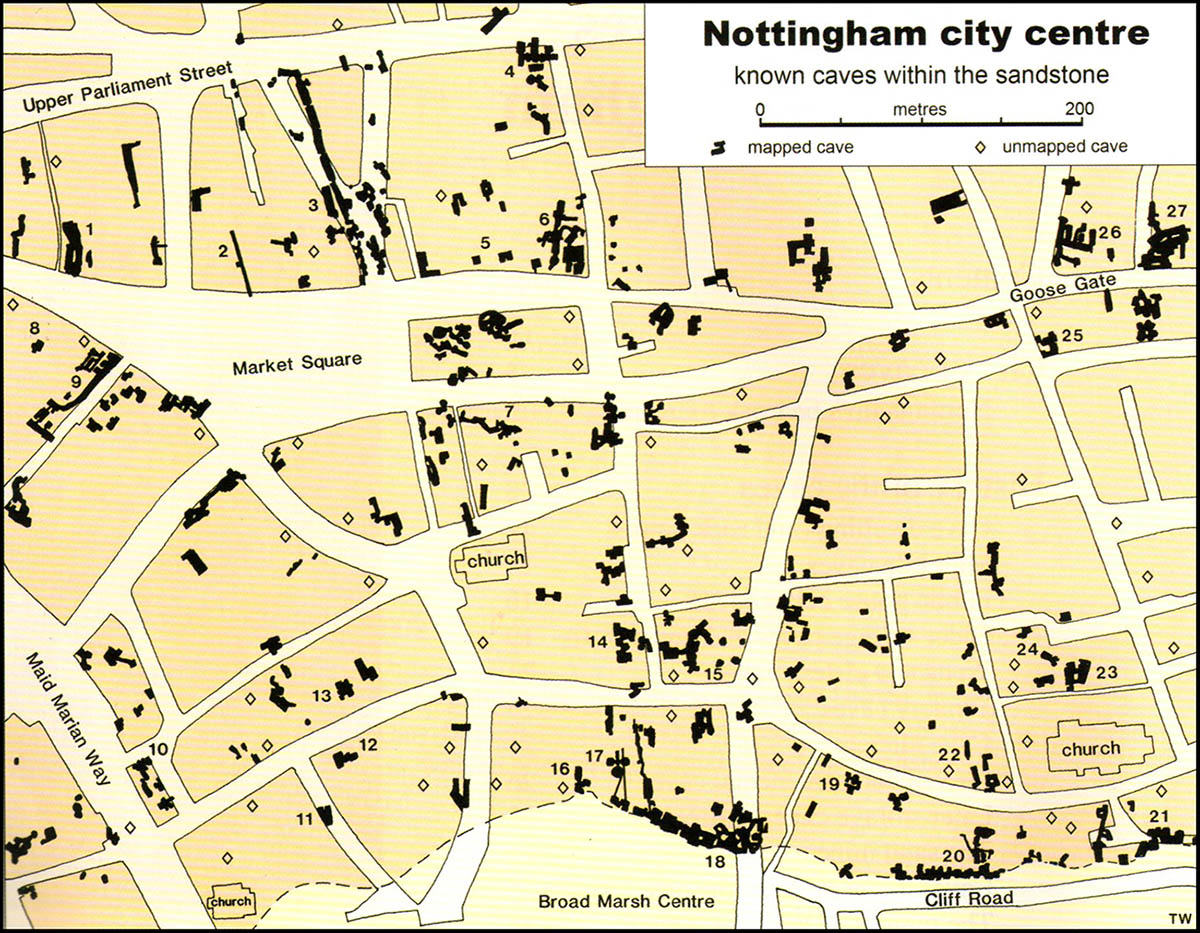

Incredibly, there are more than 450 artificial caves excavated from the sandstone beneath the streets and buildings of Nottingham, England—including, legendarily, the old dungeon that once held Robin Hood—and not all of them are known even today, let alone mapped or studied. The city sits atop a labyrinth of human-carved spaces—some of them huge—and it will quite simply never be certain if archaeologists and historians have found them all.

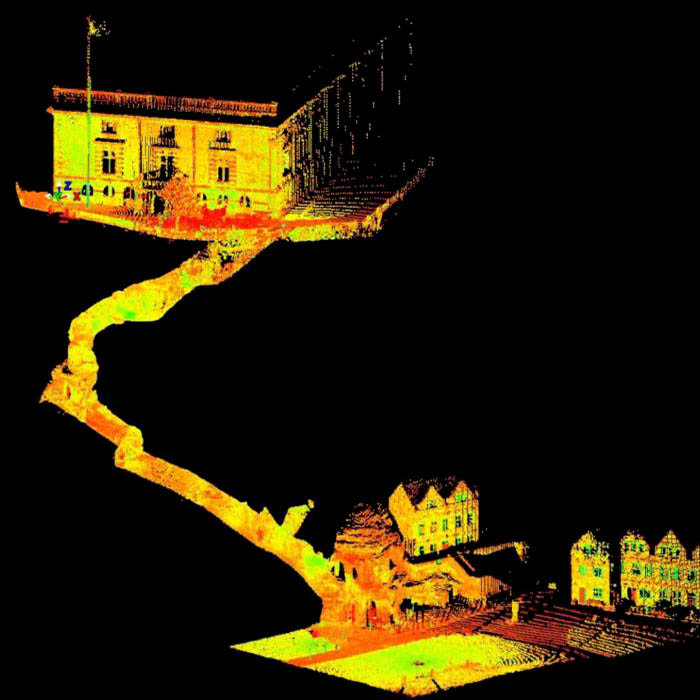

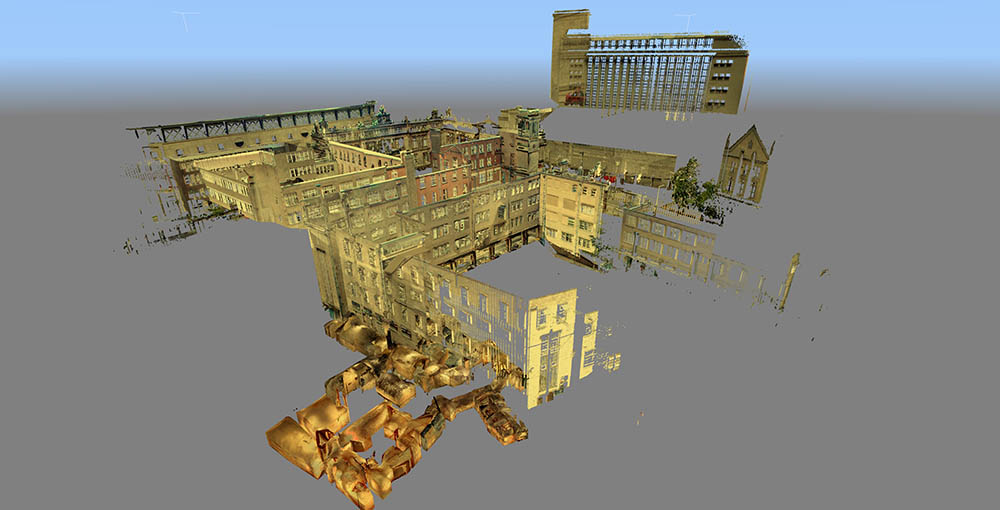

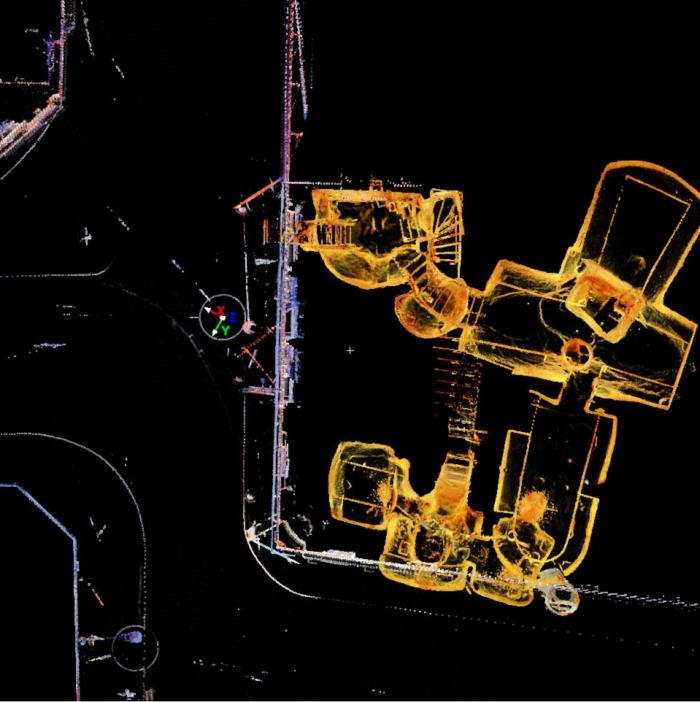

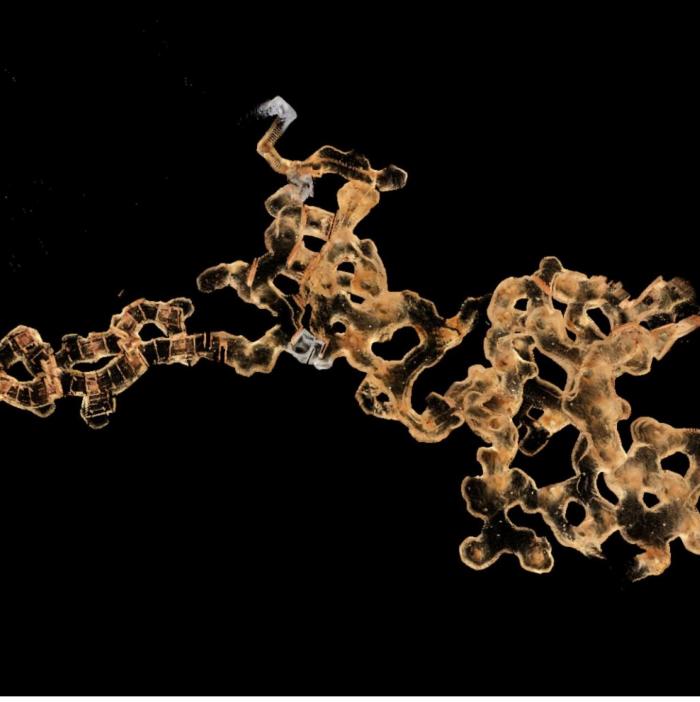

[Images: Laser scans from the Nottingham Caves Survey show Castle Rock and the Mortimer’s Hole tunnel, including, in the bottom image, the Trip to Jerusalem Pub where we met archaeologist David Strange-Walker; images like this imply an exhilarating and almost psychedelic portrait of the city as invisibly connected behind the scenes by an umbilical network of caves and tunnels. Scans courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

[Images: Laser scans from the Nottingham Caves Survey show Castle Rock and the Mortimer’s Hole tunnel, including, in the bottom image, the Trip to Jerusalem Pub where we met archaeologist David Strange-Walker; images like this imply an exhilarating and almost psychedelic portrait of the city as invisibly connected behind the scenes by an umbilical network of caves and tunnels. Scans courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

“Even back in Saxon times, Nottingham was known for its caves,” local historian Tony Waltham writes in his helpful guide Sandstone Caves of Nottingham, “though the great majority of those which survive today were cut much more recently.” From malt kilns to pub cellars, “gentlemen’s lounges” to jails, and wells to cisterns, these caves form an almost entirely privately-owned lacework of voids beneath the city.

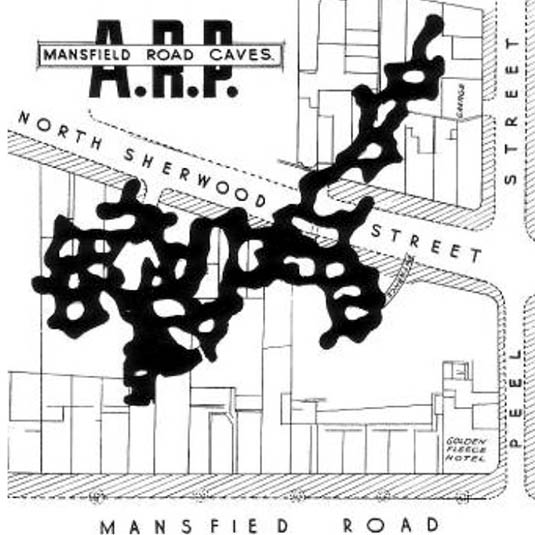

[Image: Map of only the known caves in Nottingham, and only in Nottingham’s city center; map by Tony Waltham, from Sandstone Caves of Nottingham].

[Image: Map of only the known caves in Nottingham, and only in Nottingham’s city center; map by Tony Waltham, from Sandstone Caves of Nottingham].

As Waltham explains, “Nottingham has so many caves quite simply because the physical properties of the bedrock sandstone are ideal for its excavation.” The sandstone “is easily excavated with only hand tools, yet will safely stand as an unsupported arch of low profile.”

In a sense, Nottingham is the Cappadocia of the British Isles.

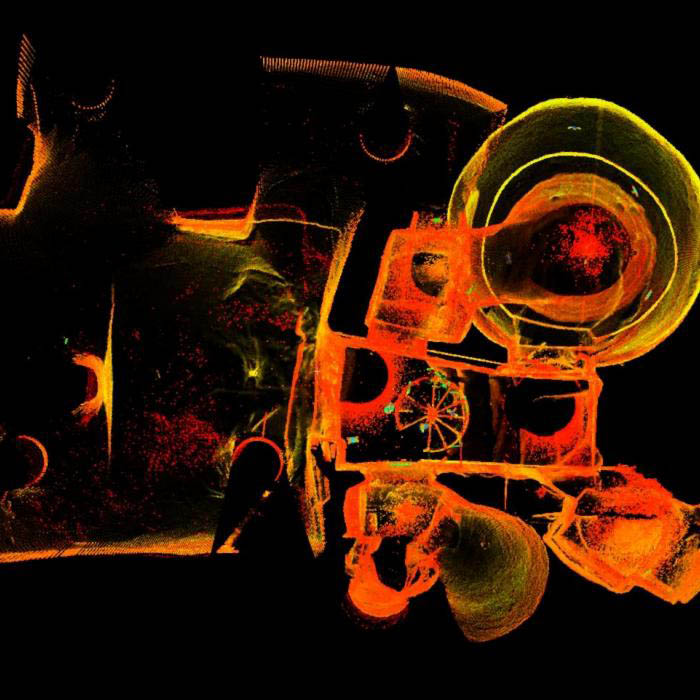

[Image: The extraordinary caves at 8 Castle Gate; scan courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

[Image: The extraordinary caves at 8 Castle Gate; scan courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

The purpose of the Nottingham Caves Survey, as their website explains, is “to assess the archaeological importance of Nottingham’s caves. Some are currently scheduled monuments and are of great local and national importance. Some are pub cellars and may seem less vital to the history of the City.”

Others, I was soon to learn, have been bricked off, taken apart, filled in, or forgotten.

“All caves that can be physically accessed will be surveyed with a 3D laser scanner,” the Survey adds, “producing a full measured record of the caves in three dimensions. This ‘point cloud’ of millions of individual survey points can be cut and sliced into plans and sections, ‘flown through’ in short videos, and examined in great detail on the web.”

[Video: One of very many laser-scan animations from the Nottingham Caves Survey].

While over in England a few weeks ago, I got in touch with archaeologist David Strange-Walker, the project’s manager, and arranged for a visit up to Nottingham to learn more about the project. Best of all, David very generously organized an entire day’s worth of explorations, going down into many of the city’s underground spaces in person with David himself as our guide. Joining me on the trip north from London was Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography; architect Mark Smout of Smout Allen and co-author of the fantastic Pamphlet Architecture installment, Augmented Landscapes; and Mark’s young son, Ellis.

[Image: Artificially enlarged pores in the sandstone; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Artificially enlarged pores in the sandstone; photo by BLDGBLOG].

We met the very likable and energetic David—who was dressed for a full day of activity, complete with a well-weathered backpack that we’d later learn contained hard hats and floodlights for each of us—outside Nottingham’s Trip to Jerusalem pub.

Rather than kicking off our visit with a pint, however, we simply walked inside to see how the pub had been partially built—that is, expanded through deliberate excavation—into the sandstone cliffside.

The building is thus more like a facade wrapped around and disguising the artificial caves behind it; walking in past the bar, for instance, you soon notice ventilation shafts and strange half-stairways, curved walls and unpredictable acoustics, as the “network of caves” that actually constitutes the pub interior begins to reveal itself.

[Image: A laser scan showing the umbilical connection of Mortimer’s Hole, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

[Image: A laser scan showing the umbilical connection of Mortimer’s Hole, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

My mind was already somewhat blown by this, though it was just the barest indication of extraordinary spatial experiences yet to come.

[Image: Examining sandstone with Dr. David Strange-Walker; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Examining sandstone with Dr. David Strange-Walker; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Wasting no time, we headed back outside, where afternoon rain showers had begun to blow in, and David introduced us to the sandstone cliff itself, pointing out both natural and artificially enlarged pores pockmarking the outside.

The sandstone formations or “rock units” beneath the city, as Tony Waltham explains, “were formed as flash flood sediments in desert basins during Triassic times, about 240 million years ago, when Britain was part of a hot and dry continental interior close to the equator. Subsequent eons of plate tectonic movements have brought Britain to its present position; and during the same time, the desert sediments have been buried, compressed and cemented to form moderately strong sedimentary rocks.”

The city is thus built atop a kind of frozen Sahara, deep into which we were about to go walking.

[Image: A gate in the cliff; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A gate in the cliff; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Outside here in the cliff face, small openings led within to medieval tunnels and stairs—including the infamous Mortimer’s Hole—that themselves curled up to the top of the plateau; doors in the rock further up from the Trip to Jerusalem opened onto what were now private shooting ranges, of all things; and, with a laugh, David pointed out shotcrete cosmetic work that had been applied to the outer stone surface.

[Image: Artificial shotcrete geology; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Artificial shotcrete geology; photo by BLDGBLOG].

We headed from there—walking a brisk pace uphill into the town center—with David casually narrating the various basements, cellars, tunnels, and other urban perforations that lay under the buildings around us, as if we were traveling through town with a human x-ray machine for whom the city was an archaeologically rich cobweb of underground loops and dead-ends.

We soon ended up at the old jails of the Galleries of Justice. A well-known tourist destination, complete with costumed re-enactors, the building sits atop several levels of artificial caves that are well worth exploring.

[Image: Scan of the Guildhall caves, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

[Image: Scan of the Guildhall caves, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

We were joined at this point by the site’s director, who generously took time out of his schedule to lead us down into parts of the underground complex that are not normally open to the general public.

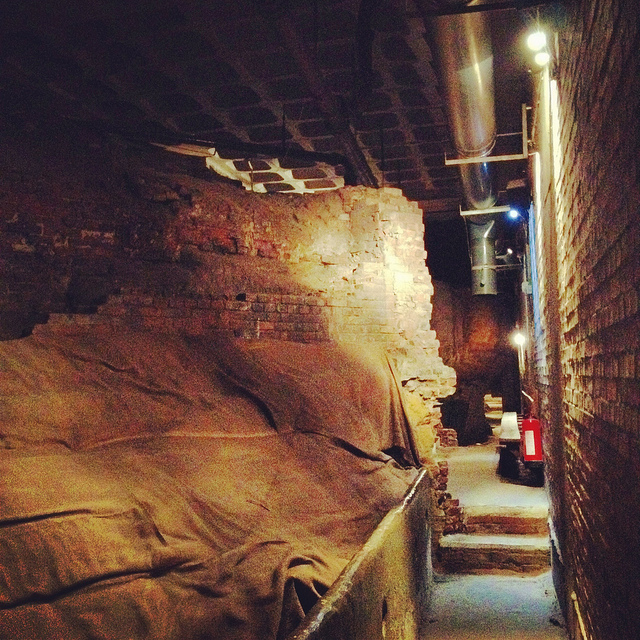

Heading downward—at first by elevator—we eventually unlocked a door, stepped into a tiny room beneath even the jail cells, crouching over so as not to bang our heads on the low ceiling, and we leaned against banded brick pillars that had been added to help support all the architecture groaning above us.

Avoiding each other’s flashlight beams, we listened as our two guides talked about the discovery—and, sadly, the willful reburial—of caves throughout central Nottingham.

[Image: Brick pillars below Nottingham; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Brick pillars below Nottingham; photo by BLDGBLOG].

We learned, for instance, that, elsewhere in the city, there had once been a vacuum shop with a cave beneath it; if I remember this story correctly, the shop’s owners had the habit of simply discarding broken and unsold vacuum cleaners into the cave, inadvertently creating a kind of museum of obsolete vacuum parts. Discontinued models sat in the darkness—a void full of vacuums—as the shop went out of business.

We heard, as well, about a nearby site where caves had been discovered beneath a bank during a recent process of renovation and expansion—but, fearing discovery of anything that might slow down the bank’s architectural plans, the caves were simply walled up and left unexplored. They’re thus still down there, underneath and behind the bank, their contents unknown, their extent unmapped—a fate, it seems, shared by many of the caves of Nottingham.

Rather than being greeted by the subterranean and historical wonder that such structures deserve—and I would argue that essentially all of subterranean Nottingham should be declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site—the caves are too often treated as little more than annoying construction setbacks or anomalous ground conditions, suitable only for bricking up, filling with concrete, or forgetting. If the public thinks about them at all, in seems, it is only long enough to consider them threats to building safety or negative influences on property value.

[Images: Learning about caves; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Learning about caves; photos by BLDGBLOG].

In any case, on our way out of the Galleries of Justice, we lifted up a ventilation grill in the floor and looked down into a small vertical shaft, too narrow and contorted even for Ellis to navigate, and we learned that there are urban legends that this particular shaft leads down to a larger room in which Robin Hood himself was once held… But we had only enough time to shine our flashlights down and wonder.

[Images: Ellis Smout looks for Robin Hood below; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Ellis Smout looks for Robin Hood below; photos by BLDGBLOG].

From here, we headed over to our final tourist-y site of the day, which is the awesomely surreal City of Caves exhibition, located in Nottingham’s Broad Marsh shopping mall.

You literally take an escalator down into an indoor mall, where, amidst clothing outlets and food courts, there is an otherwise totally mundane sign pointing simply to “Caves.”

If you didn’t know about Nottingham’s extensive sub-city, this would surely be one of the most inexplicable way-finding messages in mall history.

[Image: Caves; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: Caves; photo by Nicola Twilley].

Here, where we picked our copy of Tony Waltham’s Sandstone Caves of Nottingham pamphlet, from which I’ve been quoting, we learned quite a bit more about how the city has grown, how the caves themselves have often been uncovered (for example, during building expansions and renovations), and what role Nottingham’s underground spaces served during the Nazi bombings of WWII.

[Image: Beneath Broad Marsh shopping mall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Beneath Broad Marsh shopping mall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

The specific underground complex beneath the shopping mall offers an interesting mix of old tanning operations and other semi-industrial, pre-modern work rooms, now overlapping with 20th-century living and basement spaces that were sliced open during the construction of the Broad Marsh mall.

[Images: Cave spaces beneath the Superstudio-like concrete grid of Nottingham’s Broad Marsh shopping Mall].

[Images: Cave spaces beneath the Superstudio-like concrete grid of Nottingham’s Broad Marsh shopping Mall].

That these caves were preserved at all is testament to the power of local conservationists, as the historically rich and spatially intricate rooms and corridors would have been gutted and erased entirely during post-War reconstruction without their intervention.

As it now stands, the mall is perched above the caves on concrete pillars, with the effect that curious shoppers can wander down into the caves through an entrance that could just as easily lead to a local branch of Accessorize.

[Image: A well bucket in the caves beneath Broad Marsh; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A well bucket in the caves beneath Broad Marsh; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Again, we were fortunate to be taken down into some off-limits areas, stepping over lights and electric wires and peering ahead into larger rooms not on the tourist route.

[Images: Lines of lights we switched on in one of the off-limits rooms below Broad Marsh; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Lines of lights we switched on in one of the off-limits rooms below Broad Marsh; photo by BLDGBLOG].

This included stepping outside at one point to wander through an overgrown alleyway behind the mall. Small openings even back here stretched beneath and seemingly into the backs of shops; one doorway, a short scramble up a hill of weed-covered rubble, appeared to contain a half-collapsed spiral staircase installed inside a brick-lined sandstone opening.

[Image: A doorway to voids behind Broad Marsh Centre; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A doorway to voids behind Broad Marsh Centre; photo by BLDGBLOG].

At this point, we began to joke about the ease with which it seemed you could plan a sort of speleological super-heist, breaking into shops from below, as an entire dimension of the city seemed to lie unwatched and unprotected.

Nottingham, it appeared, is a city of nothing but doors and openings, holes, pores, and connections, complexly layered knots of space coiling beneath one building after another, sometimes cutting all the way down to the water table.

Incredibly, the day only continued to build in interest, reaching near-impossible urban sights, from catacombs in the local graveyard to a mind-bending sand mine that whirled and looped around like smoke rings beneath an otherwise quiet residential neighborhood.

Leaving the mall behind, and maintaining a brisk pace, David took us further into the city, where our next stop was the Old Angel Inn, another pub with an extensive cellar of caves, in this case accessed through a deceptively workaday door next to an arcade game.

[Images: The Old Angel Inn (top), including the door inside the pub that leads down to the caves below; photos by Nicola Twilley].

[Images: The Old Angel Inn (top), including the door inside the pub that leads down to the caves below; photos by Nicola Twilley].

Once again, it can hardly be exaggerated how easy it would be to visit or even live in Nottingham and have absolutely no idea that underground spaces such as this can be found almost anywhere. As Tony Waltham points out, “It would be a fair assumption that every building or site within the old city limits either has or had some form of cave beneath it. About 500 caves are now known, and this may be only half the total number that have been excavated under Nottingham.”

[Images: The caves of the Old Angel Inn, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

[Images: The caves of the Old Angel Inn, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

In any case, “Although the Old Angel is a ‘modern’ brick building,” as the Nottingham Caves Survey describes the pub on its website, “an investigation of the caves below reveals stone walls belonging to an earlier incarnation. It is likely that there were buildings on this site as far back as the Anglo-Saxon period. Whether the caves beneath are also this old cannot be demonstrated definitively.”

Typical, as well, for these types of pub caves, we found ventilation and delivery tunnels leading back up to the surface, and the walls themselves are lined with long benches, perfect for sitting below ground and, provided you have candles or a flashlight along with you, enjoying a smoke and a pint of beer. As Tony Waltham explains, pub cellars often include “perimeter thralls,” or “low ledges cut in the rock,” normally used for storing kegs and barrels of beer but quite easily repurposed for a quick sit-down.

But I sense I’m going on way too long about all this, especially because the two most memorable details of the entire day were yet to come.

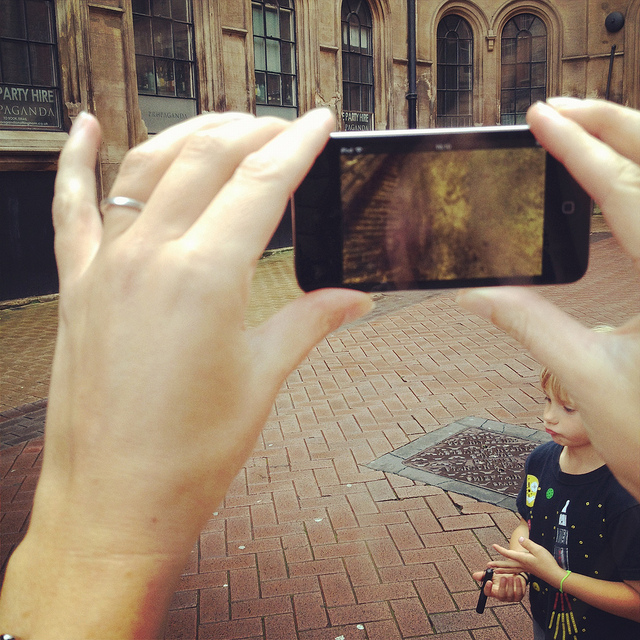

Jumping forward a bit, we left the Old Angel and followed some twists and turns in the street to find ourselves standing outside a nightclub called Propaganda.

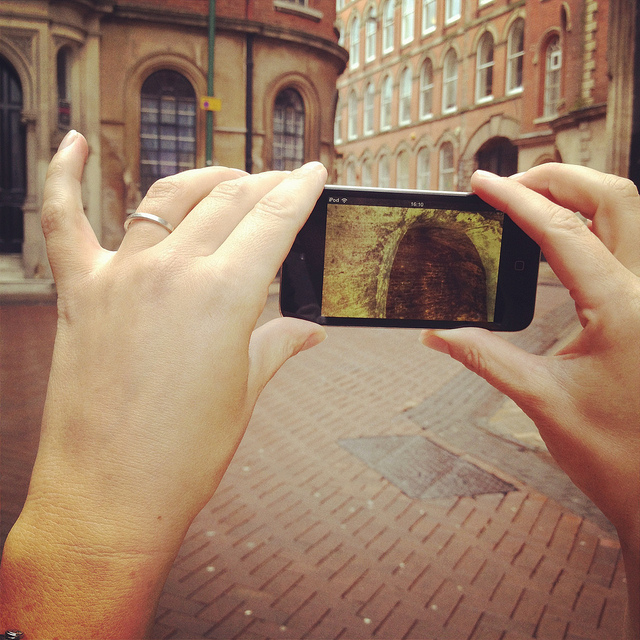

Here, David revealed that he has been working on what, in my opinion, will easily be one of the must-have apps of the year. In a nutshell, David has managed to make the subterranean 3D laser-scans of the Nottingham Caves Survey accessible by location, such that, holding up his iPod Touch, he demonstrated that you could, in effect, scan the courtyard we were standing in to see the caves, tunnels, stairways, cellars, vents, storage rooms, and more that lay hidden in the ground around us.

[Images: We test-drive the cave-spotting app; bottom photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Images: We test-drive the cave-spotting app; bottom photo by Nicola Twilley].

Ideally, once the Survey’s extensive catalog of 3D visualizations and laser point-clouds has been made available and the app is ready for public download, you will be able to walk through the city of Nottingham, smartphone in hand, revealing in all of their serpentine complexity the underground spaces of the city core.

For anyone who has ever dreamt of putting on x-ray glasses and using them to explore architectural space, this app promises to be a thrilling and vertiginous way to experience exactly that—peering right through the city to see its most ancient foundations.

[Video: A fly-through of the Propaganda Nightclub malting caves].

I, for one, can’t wait to see what David and the Nottingham Caves Survey do with the finished application and I eagerly await its public availability.

[Image: Mark Smout looks for caves in the sky; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: Mark Smout looks for caves in the sky; photo by Nicola Twilley].

I’ll wind up this already quite long post with just a few more highlights.

Nottingham’s Rock Cemetery, north from the center of town along the Mansfield Road, contains, among other things, the collapsed remains of a sand mine. Three of the mine’s old entrances are now gated alcoves surrounded by graves, like something out of Dante. They “are the only surviving remnants of the mine,” Waltham writes in his pamphlet.

[Images: Nottingham’s Rock Cemetery, where archaeologist David Strange-Walker explained the history of the local landscape].

[Images: Nottingham’s Rock Cemetery, where archaeologist David Strange-Walker explained the history of the local landscape].

However, an ambitious plan to carve sizable catacombs, inspired by Paris and Rome, through the sandstone beds of the ancient desert here resulted in the never-completed Catacomb Caves, “probably done in 1859-63,” Waltham suggests. These long arched tunnels, accessible through one of the gates described above, eventually lead to a radial terminus from which branch the unused proto-catacombs.

The air there is cloudy with sand—leading me, several days later, to experience a brief attack of hypochondria, worried about developing silicosis—the walls are graffiti’d, and years of trash are piled on the sides of the sandy floor (which has since taken on the characteristics of a dune sea in places, as 150 years of footfall and a collapsing ceiling have led to the appearance of drifts).

[Images: The Rock Cemetery catacomb gates].

[Images: The Rock Cemetery catacomb gates].

What was so extraordinary here, among many other things, was that, for most of this walk through the catacombs, we were actually walking below the graves, meaning that people were buried above us in the earth. At the risk of overdoing it, this felt not unlike becoming aware of an altogether different type of constellation, with bodies and all the stories their lives could tell held above us in a terrestrial sky like legends and heroes, like Orion and Cassiopeia, as we looked up at the vaulted ceiling, flashlights in hand.

[Image: Inside the catacombs; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: Inside the catacombs; photo by Nicola Twilley].

But the best site of all was next.

[Image: A door on the street—the black door with bars—leading down into a sand mine; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A door on the street—the black door with bars—leading down into a sand mine; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Serving as something of the ultimate proof that Nottingham is a city of overlooked doors that lead into the underworld, there were two locked doors—one of which (the black door, near the sidewalk) appears in the photo, above, another of which, on a street nearby, leads down into the Peel Street Caves—simply sitting there on the sidewalk that, if opened, will take you down into extensive and now defunct sand mines. David’s laser-scans of these for the Nottingham Caves Survey are absolutely gorgeous, as you can see, below.

[Image: The Peel Street Caves sand mine, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

[Image: The Peel Street Caves sand mine, courtesy of the Nottingham Caves Survey].

For a variety of reasons, I am going to avoid being too specific about some of the details here, but, aside from that, I can only enthuse about the experience of donning our hard hats and heading down several flights of comparatively new concrete steps into a coiling and vast artificial cavern from the 19th century, one we spent nearly an hour exploring.

[Image: Nicola Twilley and Mark Smout head down into the sand mine; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Nicola Twilley and Mark Smout head down into the sand mine; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Getting lost down there would be so absurdly easy that it is frightening even to contemplate, and, in case the group of us somehow got split up or our batteries ran out of juice, we joked about—if only we could remember them—the easy techniques for navigating a labyrinth offered in Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose.

[Image: Many of these way-finding signs are actually incorrect, David explained, and seem to have been painted as a kind of sick joke by someone several years ago; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Many of these way-finding signs are actually incorrect, David explained, and seem to have been painted as a kind of sick joke by someone several years ago; photos by BLDGBLOG].

Avoiding such a fate, however, we found graffiti and men’s and women’s latrines; we popped our heads through holes allowing glimpse of other levels; and we cracked our helmets loudly against the low and rough roof more times than I could count.

[Images: Inside the sand mine; all photos by Nicola Twilley].

[Images: Inside the sand mine; all photos by Nicola Twilley].

And even that doesn’t complete the day. From here, heading back out onto the street through a nondescript steel door, as if we had been doing nothing more than watching football in someone’s basement, we went on to eat pie and chips in a restaurant built partially into a cave; we walked back across town, returning to where we started, talking about the future and seemingly obvious possibility of Nottingham’s caves being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and thus saved from their all but inevitable destruction (it’s easy to imagine a future in which a tour like the one David gave us will be impossible for lack of caves to see); and we all said goodbye beneath an evening sky cleared of clouds as a late-day breeze began to cut through town.

[Image: Mark & Ellis Smout explore our final “underground” space of the day, the magnificent Park Tunnel; the banded strata clearly visible in the walls show how the tunnel was carved through the dunes of an ancient desert. Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Mark & Ellis Smout explore our final “underground” space of the day, the magnificent Park Tunnel; the banded strata clearly visible in the walls show how the tunnel was carved through the dunes of an ancient desert. Photo by BLDGBLOG].

David proved to be a heroic guide that day. His energy never flagged throughout the tour, and he never once appeared impatient with or exhausted by any of our often ridiculous questions—not to mention our tourists’ insistence on pausing every three or four steps to take photographs—and he remained always willing to stay underground far longer than he had originally planned, all this despite having never met any of us before in person and only communicating with me briefly via a flurry of emails the week before.

Meeting David left me far more convinced than I already was that the Nottingham Caves Survey fully deserves the financial support of individuals and institutions, so that it can complete its ambitious and historically valuable work of cataloging Nottingham’s underground spaces and making that knowledge freely accessible to the general public.

Weirdly, England has within its very heart a region deserving comparison to Turkish Cappadocia—yet very few people even seem to know that this subterranean world exists. There very well could be more than 1,000 artificial caves beneath the city, many of them fantastically elaborate, complete with fine carvings of lions and ornate stairwells, and it is actually somewhat disconcerting to think that people remain so globally unaware of Nottingham’s underground heritage.

With any luck, the work of David Strange-Walker, Trent & Peak Archaeology, and the Nottingham Caves Survey will help bring this extraordinary region of the earth the attention—and, importantly, the focused conservation—it is due.

(For further reading, don’t miss Nicola Twilley’s write-up of the tour on her own blog, Edible Geography; and Tony Waltham’s Sandstone Caves of Nottingham, cited extensively in this post, is worth a read if you can find a copy).

Buncefield Bomb Garden

[Image: The Buncefield explosion, via the BBC].

[Image: The Buncefield explosion, via the BBC].

In one of the more interesting landscape design stories I’ve read this year, New Scientist reported back in March that the massive, December 2005 explosion at a fuel-storage depot called Buncefield in England, might have been strongly assisted by the site’s landscaping.

“A few years ago no one would have predicted that a row of trees and shrubs could make the difference between a serious fire and a catastrophic explosion,” the magazine suggests. But now, it’s becoming a reasonably accepted notion that the physical layout of the Buncefield site’s plantlife—from the “shrubs and small trees” down to their individual “twigs and branches”—can work to contain and concentrate, and, worse, add explosive surface area to what would otherwise have simply been a gas leak.

Indeed, the ongoing investigation at Buncefield “might change the way storage depots, refineries and pipelines are designed, and how the sites are landscaped [emphasis added]. Along with conventional safety features like sensors and alarms, site operators may have to rethink the way that trees, hedges and shrubs are positioned.” Investigators have concluded that “even structures on nearby commercial developments could help to accelerate a flame,” meaning that, in the design of any landscape, from industrial parks to corporate lawns, there is a previously unknown capacity for detonation.

What’s incredible about this—if proven true—is that the potentially explosive landscaping of sites such as Buncefield might suggest, according to New Scientist, new geometries or diagrammatic possibilities for the design of jet engines, in particular “a novel aircraft propulsion system called a pulse detonation engine.” The garden as jet engine!

Putting this into the context of other landscape typologies, such as ritual gardens or sacred groves—as if we might someday have orchards that churn and pulse with controlled coils of fire, like the engine of some vast arboreal machine—makes this terrifying topographical phenomenon seem all the more mythic and extraordinary.

(Previously on BLDGBLOG: Star Garden).

An edge over which it is impossible to look

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth at full drain, photographed by Flickr user Serigrapher].

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth at full drain, photographed by Flickr user Serigrapher].

Nearly half a year ago, a reader emailed with a link to a paper by Andrew Crompton, called “Three Doors to Other Worlds” (download the PDF). While the entirety of the paper is worth reading, I want to highlight a specific moment, wherein Crompton introduces us to the colossal western bellmouth drain of the Ladybower reservoir in Derbyshire, England.

His description of this “inverted infrastructural monument,” as InfraNet Lab described it in their own post about Crompton’s paper—adding that spillways like this “maintain two states: (1) in use they disappear and are minimally obscured by flowing water, (2) not in use they are sculptural oddities hovering ambiguously above the water line”—is spine-tingling.

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by John Fielding, via Geograph].

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by John Fielding, via Geograph].

“What is down that hole is a deep mystery,” Crompton begins, and the ensuing passage deserves quoting in full:

Not even Google Earth can help you since its depths are in shadow when photographed from above. To see for yourself means going down the steps as far as you dare and then leaning out to take a look. Before attempting a descent, you might think it prudent to walk around the hole looking for the easiest way down. The search will reveal that the workmanship is superb and that there is no weakness to exploit, nowhere to tie a rope and not so much as a pebble to throw down the hole unless you brought it with you in the boat. The steps of this circular waterfall are all eighteen inches high. This is an awkward height to descend, and most people, one imagines, would soon turn their back on the hole and face the stone like a climber. How far would you be willing to go before the steps became too small to continue? With proper boots, it is possible to stand on a sharp edge as narrow as a quarter of an inch wide; in such a position, you will risk your life twisting your cheek away from the stone to look downward because that movement will shift your center of gravity from a position above your feet, causing you to pivot away from the wall with only friction at your fingertips to hold you in place. Sooner or later, either your nerves or your grip will fail while diminishing steps accumulate below preventing a vertical view. In short, as if you were performing a ritual, this structure will first make you walk in circles, then make you turn your back on the thing you fear, then give you a severe fright, and then deny you the answer to a question any bird could solve in a moment. When you do fall, you will hit the sides before hitting the bottom. Death with time to think about it arriving awaits anyone who peers too far into that hole.

“What we have here,” he adds, “is a geometrical oddity: an edge over which it is impossible to look. Because you can see the endless walls of the abyss both below you and facing you, nothing is hidden except what is down the hole. Standing on the rim, you are very close to a mystery: a space receiving the light of the sun into which we cannot see.”

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by Peter Hanna, from his trip through the Peak District].

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by Peter Hanna, from his trip through the Peak District].

Crompton goes on to cite H.P. Lovecraft, the travels of Christopher Columbus, and more; again, it’s worth the read (PDF). But that infinitely alluring blackness—and the tiny steps that lead down into it, and the abyssal impulse to see how far we’re willing to go—is a hard thing to get out of my mind.

(Huge thanks to Kristof Hanzlik for the tip!)

Shelved in the Sky

I couldn’t resist this photo of a man blown off his feet by high winds on the British coast.

[Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the Guardian].

[Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the Guardian].

How could we take better spatial advantage of meteorological situations like this, I wonder, whether that means designing parachute-like clothing lines for weekend air-surfing or perhaps manufacturing perfectly weighted hovering objects so that we could shelve things in the air, stationary but airborne, even whole rooms lifting off the ground to pause, several feet above the surface of the earth, looking out over the battered sea?

Maunsell Towers

[Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

[Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

I missed an amazing opportunity the other week to visit the Maunsell Towers – aka the Maunsell Sea Forts – with Nick Sowers, author of an excellent Archinect school blog and one of my students from this summer’s studio down on Cockatoo Island in Sydney.

For the last year or so, Nick has been traveling around the world on a much-deserved John K. Branner Fellowship, documenting army bases, abandoned bunkers, and other sites of historical military interest. From South Korea to the Maginot Line, from classical war zones and medieval walled cities to “bunker recycling services” and D-Day, Nick’s itinerary is breath-taking. It is also, I hope, intriguing enough to catch the eye of future publishers or gallerists who might want to give Nick the space in which to break down all that he’s seen; there are very many of us who would love to learn more.

Of course, we could also hear more about his trip: Nick is acoustically-inclined, and he has been documenting the sounds of these militarized landscapes over on another blog he runs, called Soundscrapers.

[Images: Photos by Nick Sowers].

[Images: Photos by Nick Sowers].

So Nick and his wife were in England the other week, and we unfortunately missed meeting up – but they managed to take a boat tour out to the Maunsell Sea Forts, iconic architectural structures in the Thames Estuary, inspirations for Archigram, and one of the few real-life buildings (if you can call them that) that gave me the idea to start BLDGBLOG. In fact, I’ve mentioned these places in lectures and I’ve posted about them on the blog before – but I’ve never had a chance to visit.

Nick’s photos, presented here, alongside photos by Pete Speller, will tell the story instead.

[Images: Photos by Nick Sowers].

[Images: Photos by Nick Sowers].

As Underground Kent explains, “The Thames Estuary Army Forts were constructed in 1942 to a design by Guy Maunsell.”

Their purpose was to provide anti-aircraft fire within the Thames Estuary area. Each fort consisted of a group of seven towers with a walkway connecting them all to the central control tower. The fort, when viewed as a whole, comprised one Bofors tower, a control tower, four gun towers and a searchlight tower. They were arranged in a very specific way, with the control tower at the centre, the Bofors and gun towers arranged in a semi-circular fashion around it and the searchlight tower positioned further away, but still linked directly to the control tower via a walkway. All the forts followed this plan and, in order of grounding, were called the Nore Army Fort, the Red Sands Army Fort and finally the Shivering Sands Army Fort. All three forts were in place by late 1943, but Nore is no longer standing. Construction of the towers was relatively quick, and they were easily floated out to sea and grounded in water no more than 30m (100ft) deep.

They thus entered into the imaginations of speculative architects everywhere; they helped give visual shape to Archigram’s Walking City; and they continue to offer a kind of real-life spatial analogue for Constant’s New Babylon for anyone with access to a boat.

[Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

[Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

Nick explained in an email that he visited the structures with Tony Pine, a “sound engineer” – i.e. pirate radio operator – who spent the afternoon “telling stories of the days in the 60s when Archigram came out to visit the structures, and also about incredibly cold winters when they burned the wood-fibre linings of the tower interiors to stay warm.”

Also along for the ride was Robin Adcroft, director of Project Redsand, who “describes himself as the caretaker of the structures.” Adcroft points out the genealogical importance of these structures:

The Thames Sea Forts are the last in a long history of British Marine Defences. The Army Anti Aircraft forts have played a significant role in post World War 2 developments. Notably in offshore fuel exploration and drilling platforms. The successful rapid deployment of the Maunsell Forts soon after led to the construction of the first offshore oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico in the late 1940s.

Both conceptually and materially, the Maunsell Towers have an architectural legacy that seems oddly under-explored.

[Images: Inside the forts; photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

[Images: Inside the forts; photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

But “it’s interesting,” Nick adds: “no one actually owns these things.”

Apparently the transport authority wanted to give Project Redsand a deed but they declined it, not wanting the liability. A ship crashed into Shivering Sand (an outpost which is visible from Redsand) in the 60s, taking out one of the towers and killing two maintenance personnel. Red Sand is not actually in the shipping lane, but it is very much a hazard. The original 1/4 inch plate steel is rusting through to a paper thickness. We had to wear hardhats when the boat pulled in next to the structures.

Project Redsand has more information about efforts to preserve the forts – and they link to this short YouTube video in which you can see how these clustered towers might be stabilized and maintained for generations to come.

[Images: Photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

[Images: Photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of Nick Sowers].

Meanwhile, be sure to follow Nick Sowers’s slowly-ending travels around the militarized world on his Archinect blog – and he can also be found on Twitter.