[Image: A Greenland ice-core at the Hayden Planetarium; for further reading, visit the U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory. Photo by Planet Taylor, used under a Creative Commons license].

[Image: A Greenland ice-core at the Hayden Planetarium; for further reading, visit the U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory. Photo by Planet Taylor, used under a Creative Commons license].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

The Crypta Balbi is a relatively recent, low-profile addition to Rome’s museum compendium. It’s billed variously—and confusingly—as a museum of archaeology, a museum of ancient Rome, and a museum of the Dark Ages. All of these descriptions are, in fact, cumulatively accurate, because the site is actually a city-block-sized core sample of Rome, threaded through with staircases, tunnels, and elevated walkways for visitors.

Crypta Balbi is located in an irregular pentagonal plot in the Campus Martius, an area that, unlike many regions in the ancient city, remained largely inhabited through the Middle Ages. In fact, according to Filippo Coarelli’s authoritative Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide, the Campus Martius was originally supposed to be kept free of buildings altogether and “reserved for military and athletic exercises.” However, historian Suetonius describes the city’s gradual encroachment, explaining that: “During his reign Augustus often encouraged the leading men of Rome to adorn the city with new monuments or to restore and embellish old ones.”

[Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via Google Maps].

[Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via Google Maps].

As a successful military general and favored member of Augustus‘s entourage, L. Cornelius Balbus the Younger stepped up to the plate, building a theater and attached crypta—a rectangular porticoed walkway where the theater’s scenery could be stored and around which the public might stroll, protected from the elements. Apparently, the Balbi Theater’s grand opening in 13 BC took place during one of the Tiber’s regular floods—meaning that it was, briefly, only accessible by boat. Nonetheless, the Theater and Crypta thrived, and they are depicted intact on a chunk of the Severan Forma Urbis, an amazing 60′-x-43′ incised marble map of the city created for public display in 203 AD.

Eventually, Rome’s earthquakes, fires, barbarian raids, and radical population shrinkage (from a million people in 367 AD to just 400,000 less than century later) combined with architectural re-use and the passage of time to take their toll. There isn’t much of the original Crypta left to see—a reconstructed stucco arch, and the massive travertine and tufa walls that now serve as foundations for modern houses in Via delle Botteghe Oscure and Via dei Delfini.

[Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae project].

[Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae project].

However, layered above the Crypta’s original floor plan are traces of this city block’s shifting usage—a condensed narrative of Rome’s destruction, accretion, and evolution. It is this series of transformations and reuses of both the Crypta and the urban space it occupies, rather than the fragmentary ancient ruins, that the museum aims to make visible. Like a series of stills from an impossible time-lapse film, the visitor who descends to the basement or climbs to the third floor can see this awkward cuboid chunk of city ruined, reshaped, reused, and reoriented over two thousand years of urban history.

Equally amazing are the expansive historical detours prompted by even trace elements in the urban core sample. For example, as early as the time of Hadrian, a “monumental” public latrine was inserted into a section of the Crypta. From the quantity of copper coins that fell, and weren’t worth recovering, archaeologists have extrapolated the amount of coinage in circulation in Western Europe during the latrine’s life-span. (Astonishingly, it was only in the 19th century that small change was to be this common again in Western Europe).

[Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta’s ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)].

[Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta’s ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)].

Two centuries later and a few feet higher, two graves bear witness to a city in ruins between the 5th and 7th centuries, as the prohibition against burial within city walls lapsed, and the dead were buried singly in abandoned buildings or beside roads. Ironically, in a museum that preserves the urban structures of each era equally, during the medieval period the Crypta actually housed one of the city’s largest lime-kilns, where the marble inscriptions, statues, and building blocks of classical Rome were brought to be crushed and melted down into lime (a key ingredient in the cement needed to build the city’s new Christian architecture).

In the 1940s, the convent that had occupied the site for the past four hundred years was demolished for a planned new Mussolini-era construction, which thankfully never materialized. Finally, in the 1980s, the Soprintendenza archeologica di Roma authorized the excavation of the abandoned city block; and, in 2002, the northwest corner was opened to the public, even as work continues on the rest of the site.

[Image: An interior view of the Crypta Balbi].

[Image: An interior view of the Crypta Balbi].

Aside from the execution, which is excellent, the very idea of a museum built into an urban core sample—a stratigraphic investigation of the shifting use of space over time—is incredibly exciting to me. Imagine a similar hollowing-out of urban space in Istanbul, Cairo, or Paris—residents as disoriented as tourists as they clamber through the hidden foundations and forms woven underneath and around their own city.

In New York, this might even be an idea whose time has come: as The New Yorker pointed out in December 2008, the expiration of a residential construction tax-abatement law encouraged builders to dig foundation trenches early, so as to secure better financing, but the subsequent recession has put many of these projects on hold, semi-permanently.

“What will become of the pits?” asks Nick Paumgarten, speculating that they could turn into “half-wild swimming holes, like the granite quarries of New England” or even “urban tar pits, entrapping and preserving in garbage and white brick dust the occasional unlucky passerby.” These are both attractive ideas, but with a little expenditure on zip-lines, elevated walkways, and interpretative signage, visitors could circulate around several millennia of Manhattan’s history, from the collision of the North African and American continental plates to the tangled evolution of New York’s water mains, via retreating glaciers and the housing bubble.

Meanwhile, back in Rome and less than a mile away from the Crypta, engineers have teamed up with the Soprintendenza to sink several new urban cores, this time in the guise of excavating the elevator and escalator shafts for a new subway line.

Angelo Bottini, director of the Soprintendenza, can hardly hide his excitement, telling the Wall Street Journal that, under usual circumstances, “We never get to dig in the center of Rome.” Sadly, it seems as though most of the finds will be documented and then destroyed, due to a shortage of museum space and the already astronomical construction costs (an estimated $375 million for one mile of track in the city center).

But how amazing would it be if the new subway station walkways and escalator shafts could themselves become Crypta Balbi-like museums of buried stratigraphy? Rome would be riddled with urban cores, awestruck tourists ascending and descending through sampled spatial histories across the city. Meanwhile the Sistine Chapel lies miraculously empty…

[Previous guest posts by Nicola Twilley include The Tree Museum, The Water Menu, Atmospheric Intoxication, and Park Stories].

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film

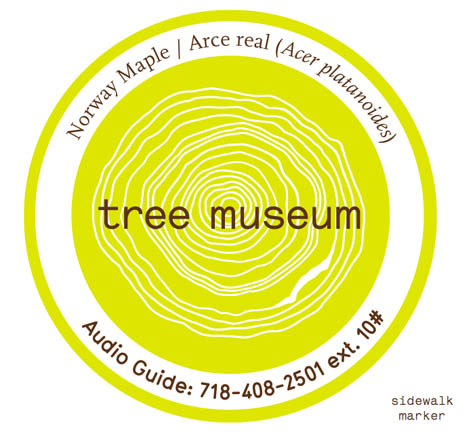

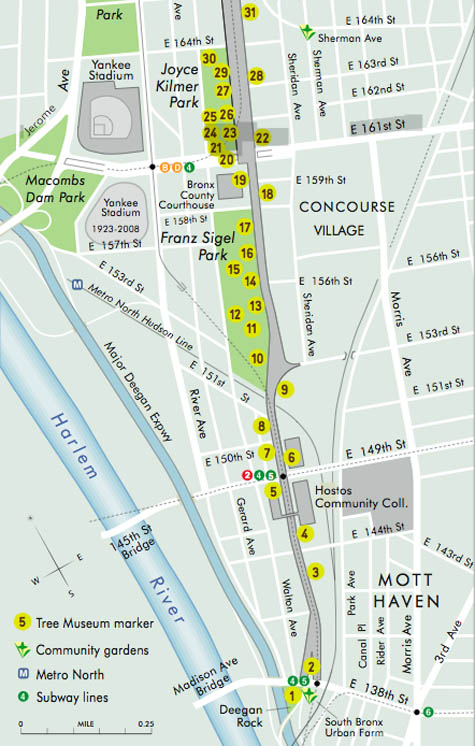

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film  [Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].

[Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number]. [Image: A section of the

[Image: A section of the  [Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].

[Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University]. [Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].

[Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten]. [Image: The Bronx

[Image: The Bronx  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Ebenezer Howard’s original scheme for the

[Image: Ebenezer Howard’s original scheme for the  [Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), ©

[Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), © [Image: From Mikey Tomkins’s series of

[Image: From Mikey Tomkins’s series of  [Image: The original fire house from

[Image: The original fire house from  [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via

[Image: 33 Thomas Street, via  The city of Venice has begun to rebrand its tap water, calling it

The city of Venice has begun to rebrand its tap water, calling it  [Image: Marcel Duchamp,

[Image: Marcel Duchamp,  [Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed being towed through Venice towards the Arsenale basin, against a backdrop of Italian palazzi].

[Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed being towed through Venice towards the Arsenale basin, against a backdrop of Italian palazzi]. [Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed goes down].

[Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed goes down]. [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Detail of a zoning map for

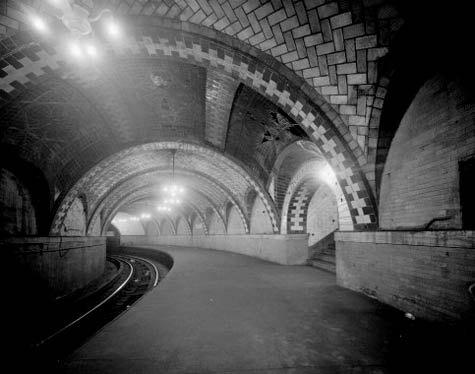

[Image: Detail of a zoning map for  [Image: The subterranean vaults of Manhattan, seen here in

[Image: The subterranean vaults of Manhattan, seen here in  [Image: The great Manhattan underdome, photo by

[Image: The great Manhattan underdome, photo by  [Image: A dream of freeways above the city, at

[Image: A dream of freeways above the city, at