As the spring semester comes to an end, and as this past Friday afternoon brought with it a guest lecture from historian James Fleming, I thought I’d offer a quick look back at some texts—mostly books—that were of particular use during the Glacier/Island/Storm studio up at Columbia.

[Image: A hike through the South Downs, photo by the author].

[Image: A hike through the South Downs, photo by the author].

I should add, though, that the following books were not assigned reading—they simply came up as frequent points of conversational reference during individual desk-crits. These were also all in addition to technical readings, done on a per-project basis, such as industry reports on maritime pharmacology, the engineering and construction of offshore structures, the ferroelectric potential of ice, surveys of atmospheric fog- and dew-harvesting techniques in southern England, and the full text of the U.N. Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques.

In turn, those were in addition to several documentary films, such as Owning the Weather, Drifting Station Alpha, and The Reef Builders; which were also on top of a field trip to the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, a visit from marine biologist Thomas Goreau, a daylong symposium looking at Glacier/Island/Storm outside of its more explicit architectural contexts with the authors of Mammoth, Quiet Babylon, and Edible Geography, and a long list of individual student interviews with experts in the field. These took place during overseas trips to destinations as far as Bali, Morocco, the Blue Hole of Belize, the South Downs, and the Swiss Alps. It’s been an awesome semester, at least from my perspective, and I’m sorry to see it go.

In any case, the following list includes texts that came up across more than one project, at multiple times during the semester for various reasons. As such, they were particularly useful in helping to generate design ideas. In no particular order:

[Images: Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control by James Fleming and Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland by Shin Egashira and David Greene].

[Images: Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control by James Fleming and Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland by Shin Egashira and David Greene].

1) “The Climate Engineers” by James Fleming. Fleming’s article is an excellent survey of the history—and possible political future—of weather-control efforts and climate-modification technology, mostly in a military context. “Assume, for just a moment,” Fleming writes, “that climate control were technically possible. Who would be given the authority to manage it? Who would have the wisdom to dispense drought, severe winters, or the effects of storms to some so that the rest of the planet could prosper? At what cost, economically, aesthetically, and in our moral relationship to nature, would we manipulate the climate?” His forthcoming book, Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control sounds fantastic, and it extends that research.

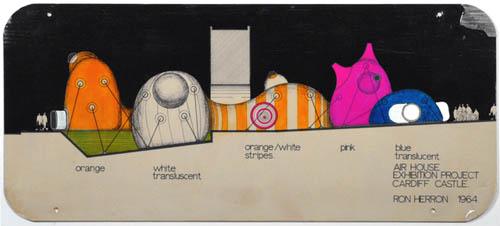

2) Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland by Shin Egashira and David Greene. I bought this book—a pamphlet, really—back in 1998, and I’ve held onto it ever since, even taking it with me on this (still ongoing) year-plus global trip. Exploring the island of Portland—from which much of London’s architectural rock was once quarried, turning the island’s profile into a negative graph of London’s expansion—from the perspective of investigative landscape design, Egashira’s and Greene’s students covered the terrain in architectural devices, machines, and mechanisms that could record wind speed, coastal barometry, island seismology, water levels, and much more (as well as simply demonstrate carpentry skills).

[Images: Spreads from Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland by Shin Egashira and David Greene].

[Images: Spreads from Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland by Shin Egashira and David Greene].

3) The Frozen Water Trade by Gavin Weightman. I first became aware of this book through an old reference on Pruned, but only managed to read it this past winter. A historical look at the early days of ice-harvesting from the surfaces of frozen ponds across New England—after which great cubes would be preserved in ice houses and in the hulls of ships, insulated with saw dust, and sold to markets as far away as India. The economics, technicalities, and strange cultural inspirations behind the ice-harvesting industry are genuinely fascinating. “Those who could afford it,” Weightman explains, “had a fresh block of ice delivered daily, for which they paid a weekly or monthly subscription”—and thus we have the deterritorialized surfaces of frozen ponds, rearranging themselves around the world by monthly subscription.

4) When the Rivers Run Dry by Fred Pearce. This book seemed like something I’d simply file away on my bookshelf for another day, but I stormed through it in less than three nights after letting myself take on the first few pages. Absurdly interesting, and almost impossible to put down, this book about freshwater and its dwindling global presence is so full of interesting material that I could refer to it again and again. Fog nets in South America, dew ponds in Sussex, desert raincatchers, and underground cisterns in China, by way of Iranian qanats, freshwater politics in the U.S. southwest, and polluted irrigation systems in India, cross with disappearing glaciers, the Amazon river, the subsidized economies of hydroelectric projects, and much more, to make a fantastic book. The author, Fred Pearce, also blogs for the Guardian.

5) Sand by Michael Welland. Welland’s book—which I have been meaning to review at great length all Spring and will finally be doing so soon—is equally fantastic. The torsional geometry of sandstorms, dune physics, military geology labs, sand forensics at murder scenes, “sand smuggling,” and large-scale anti-desertification projects in the Sahara meet high-grade silicon mines and granular deposits on Mars in Welland’s informal narrative that goes all the way around (and off) the planet. Welland, too, has a blog, Through the Sandglass, which is well worth checking out.

[Images: The Frozen Water Trade by Gavin Weightman, When the Rivers Run Dry by Fred Pearce, Sand by Michael Welland, and -arium: Weather + Architecture by Neeraj Bhatia and J. Mayer H].

[Images: The Frozen Water Trade by Gavin Weightman, When the Rivers Run Dry by Fred Pearce, Sand by Michael Welland, and -arium: Weather + Architecture by Neeraj Bhatia and J. Mayer H].

6) -arium: Weather + Architecture by Neeraj Bhatia and J. Mayer H. Published midway through the semester, Bhatia’s and Mayer’s book includes several student projects from a recent weather-design studio in Toronto, as well as the editors’ own original research into climate-modification and its possible urban futures. Bhatia’s short history of thermally regulated interior environments, and what he calls “the crisis of created climates,” is a highlight. Bhatia, of course, is co-author of the blog InfraNet Lab, whose four authors collectively participated in our Glacier/Island/Storm blog week back in February.

7) Subnature by David Gissen. Gissen’s book has already come up several times, to positive review, here on BLDGBLOG and presumably needs little introduction to long-term readers—but it’s a memorably wide-ranging look at all those other presences in the city that urbanists tend to overlook: puddles, dust, dirt, rats, weeds, and car exhaust, to name but a few. Gissen’s history of the tunnel-ventilation infrastructure of Manhattan was of particular relevance this term, as a few students and I looked briefly at the possibility of weather systems generated underneath the metropolis, as air pressure builds, moves, and dissipates throughout sewers, subway tunnels, and cross-island links. What weather-modification possibilities exist below the earth’s surface? Speculative rhetorical questions aside, Gissen’s book is valuable reading for anyone interested in the flipside of the modern city.

[Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower, ventilating the Manhattanite underworld; photo via SkyscraperPage.com].

[Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower, ventilating the Manhattanite underworld; photo via SkyscraperPage.com].

8) Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets by Mary-Ann Ray. Mary-Ann Ray’s old Pamphlet Architecture installment is still one of my favorites. As much an archaeological handbook as it is an architectural guide, Ray’s pamphlet takes us into the ruins of underground spaces around Italy, including helical stairways, spherical ice-storage facilities “with as little surface area as possible,” and vaulted secret passageways for midgets.

[Images: Subnature by David Gissen, Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets by Mary-Ann Ray, and Augmented Landscapes by Smout Allen].

[Images: Subnature by David Gissen, Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets by Mary-Ann Ray, and Augmented Landscapes by Smout Allen].

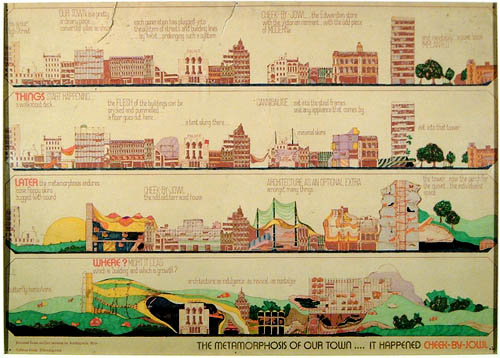

9) Augmented Landscapes by Smout Allen. Smout Allen’s work bridges landscapes, watersheds, continents, and villages, connecting architectural design to the mobile terrains of receding coastlines, wind-blown fens, and drainage canals. “In this Pamphlet,” the authors write, “we discuss five design cases.

In each the physicality of the site and the processes of environmental transformation are exploited—the intrinsic features of the landscape, the force of nature, geography, climate, geology, and land use are all scrutinized. The resulting architectural interventions respond to their dynamic and fluxing territories. The ephemeral character of the environment is reflected in the solidity of the artifacts that inhabit it as they take on a local specificity and lend to their surroundings a sense of nature illuminated.

You can read more about Smout Allen’s work courtesy of an article in the April 2010 issue of Blueprint Magazine.

[Images: Four Moleskine spreads from Augmented Landscapes by Smout Allen].

[Images: Four Moleskine spreads from Augmented Landscapes by Smout Allen].

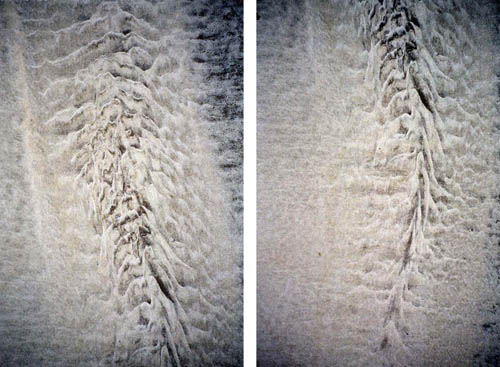

10) Mont Blanc: A Treatise on its Geodesic and Geological Constitution by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Last but not least, Viollet-le-Duc’s amazing hybrid architectural/geological analysis of the tectonic structure of Mont Blanc and its glaciers offered us several beautiful insights into the structural properties of ice flows and how they might be of interest in the context of architectural design.

[Images: From Mont Blanc by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc].

[Images: From Mont Blanc by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc].

Quoting at great length from a paper by architectural historians Martin Bressani and Robert Jan van Pelt:

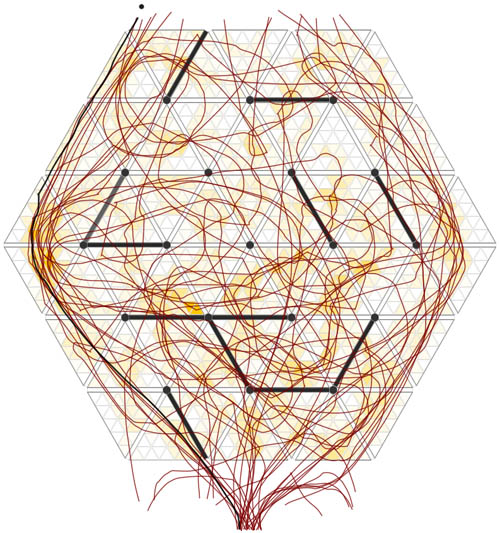

Viollet-le-Duc’s work on Mont Blanc introduces a new edge to geological discourse in architecture as compared to the painterly outlook of [John] Ruskin. Now, observations of tectonic forms not only served to see nature intensely but also, and mainly, to identify a structural logic to its complex morphology. A basic principle thus organizes Viollet-le-Duc’s analysis of the great massif: The apparent chaos of its outline is only an illusion, as “laws have ordered these forms and determined the great crystalline system.” Viollet-le-Duc’s book is essentially a description of the process of formation of Mont Blanc, using a set of fascinating drawings and diagrams as if he had been present at the time of its genesis. The book’s opening chapter confidently illustrates the initial upheaval that generated the massif: An expanded mass of soft granite (protogine) below the earth’s thick surface erupted through the crystalline crust above, producing a domical rock formation sprouting out of a buttonhole-shape slit. As it slowly cooled and crystallized, this gigantic mass of granite progressively shrank and retreated. According to Viollet-le-Duc, the subtraction process followed a very precise rhombohedral prismatic pattern consistent throughout the whole. Mont Blanc thus acts as one huge crystal formation—every edge, every peak and aiguille follows a geodesic structure. The pattern creates a network of cells, a type of formation that Viollet-le-Duc found also at the micro level in glacial formation. This hexagonal configuration, based upon the equilateral triangle, proved the most fundamental and consistent principle of organization within Viollet-le-Duc’s late writings and architecture.

Within both glaciers and large-scale rock formations, in other words, we can find formal analogies for human architectural constructions—a geometry and order to both rock and ice. Coming round nearly full circle, then, geologist Michael Welland, whose book Sand is mentioned above, wrote a blog post exploring Viollet-le-Duc’s Alpine investigations, also mentioning a kind of geological novella that Viollet-le-Duc wrote shortly before his death.

• • •Again, that’s by no means all of the material that we looked at this term, but it does give a fairly good list of the textual, historical, scientific, and architectural influences that came up repeatedly during the course.

[Image: “Beamer Bees” by Liam Young and Anab Jain].

[Image: “Beamer Bees” by Liam Young and Anab Jain]. [Image: Plug-In City by Archigram/Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton; courtesy University of Westminster].

[Image: Plug-In City by Archigram/Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton; courtesy University of Westminster]. [Images: The Rosslyn Chapel hives; photos courtesy of the Times].

[Images: The Rosslyn Chapel hives; photos courtesy of the Times]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: The Ladybower bellmouth at full drain, photographed by Flickr user

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth at full drain, photographed by Flickr user  [Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by John Fielding, via

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by John Fielding, via  [Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by

[Image: The Ladybower bellmouth, photographed by  [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Images: Movement-typologies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Movement-typologies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth,” or psycho-cybernetic human navigational testing ground, constructed near Euston Station].

[Image: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth,” or psycho-cybernetic human navigational testing ground, constructed near Euston Station].

[Images: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth”].

[Images: Sam McElhinney’s “switching labyrinth”]. [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Image: From “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

[Images: Maze-studies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney].

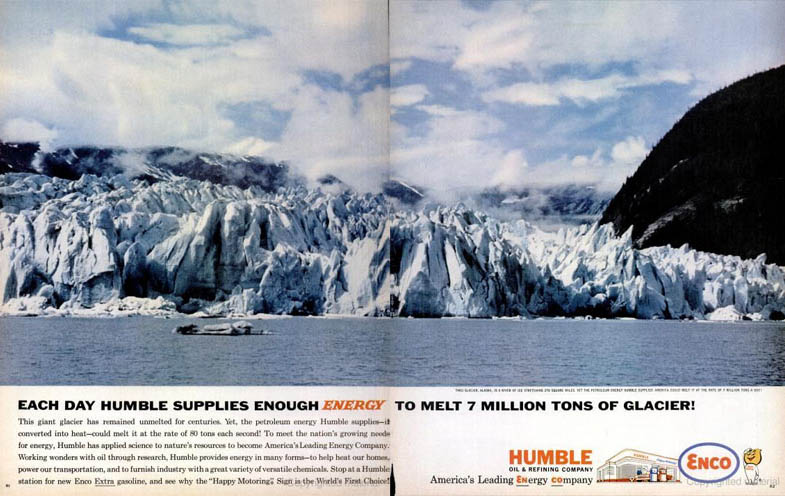

[Images: Maze-studies from “Labyrinths, Mazes and the Spaces Inbetween” by Sam McElhinney]. [Image: “Each Day Humble Supplies

[Image: “Each Day Humble Supplies  [Image: A giant battery grows in Texas; image courtesy of

[Image: A giant battery grows in Texas; image courtesy of  [Image: Engine house of an

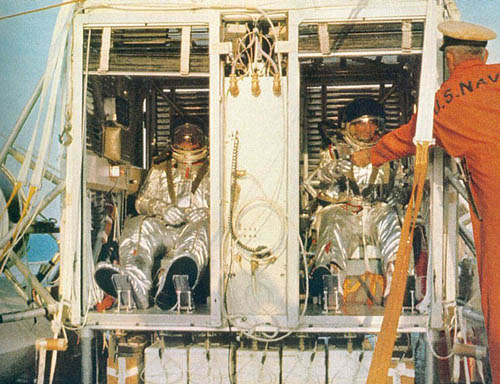

[Image: Engine house of an  [Image: Strato Lab; photo via

[Image: Strato Lab; photo via  [Image: Strato Lab as sky-throne; photo via

[Image: Strato Lab as sky-throne; photo via  [Image: Strato Lab; photo via

[Image: Strato Lab; photo via  [Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal

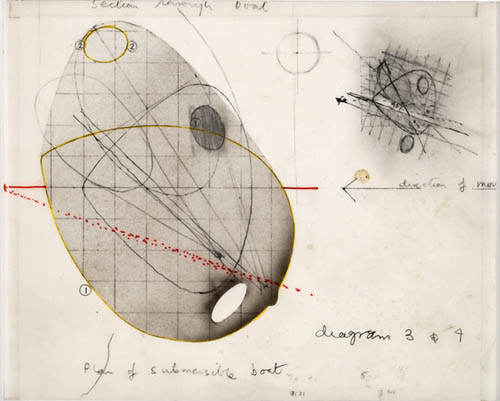

[Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal  [Image: “Proposal for a

[Image: “Proposal for a  [Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a

[Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a  [Image: Proposal “

[Image: Proposal “ [Image: A hike through the

[Image: A hike through the  [Images:

[Images:

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from  [Images:

[Images:  [Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower, ventilating the Manhattanite underworld; photo via

[Image: Holland Tunnel exhaust tower, ventilating the Manhattanite underworld; photo via  [Images:

[Images:

[Images: Four Moleskine spreads from

[Images: Four Moleskine spreads from

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: The walls of

[Image: The walls of  [Images: Extraordinary photographs of sand by

[Images: Extraordinary photographs of sand by  [Image: A still from Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, courtesy of

[Image: A still from Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, courtesy of

[Images: A rotating hall and fight scene from Inception, courtesy of

[Images: A rotating hall and fight scene from Inception, courtesy of  [Image: From Inception by Christopher Nolan, courtesy of

[Image: From Inception by Christopher Nolan, courtesy of