[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

One of the most interesting sites from a course I taught several years ago at Columbia—Glacier, Island, Storm—was the glacial border between Italy and Switzerland.

The border there is not, in fact, permanently determined, as it actually shifts back and forth according to the height of the glaciers.

This not only means that parts of the landscape there have shifted between nations without ever really going anywhere—a kind of ghost dance of the nation-states—but also that climate change will have a very literal effect on the size and shape of both countries.

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy swisstopo].

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy swisstopo].

This could result in the absurd scenario of Switzerland, for example, using its famed glacier blankets, attempting to preserve glacial mass (and thus sovereign territory), or it might even mean designing and cultivating artificial glaciers as a means of aggressively expanding national territory.

As student Marissa Looby interpreted the brief, there would be small watchtowers constructed in the Alps to act as temporary residential structures for border scientists and their surveying machines, and to function as actual physical marking systems visible for miles in the mountains, somewhere between architectural measuring stick for glacial growth and modular micro-housing.

But the very idea that a form of thermal warfare might break out between two countries—with Switzerland and Italy competitively growing and preserving glaciers under military escort high in the Alps—is a compelling (if not altogether likely) thing to consider. Similarly, the notion that techniques borrowed from landscape and architectural design could be used to actually make countries bigger—eg. through the construction of glacier-maintenance structures, ice-growing farms, or the formatting of the landscape to store seasonal accumulations of snow more effectively—is absolutely fascinating.

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

I was thus interested to read about a conceptually similar but otherwise unrelated new project, a small exhibition on display at this year’s Venice Biennale called—in English, somewhat unfortunately—Italian Limes, where “Limes” is actually Latin for limits or borders (not English for a small acidic fruit). Italian Limes explores “the most remote Alpine regions, where Italy’s northern frontier drifts with glaciers.”

In effect, this is simply a project looking at this moving border region in the Alps from the standpoint of Italy.

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

As the project description explains, “Italy is one of the rare continental countries whose entire confines are defined by precise natural borders. Mountain passes, peaks, valleys and promontories have been marked, altered, and colonized by peculiar systems of control that played a fundamental role in the definition of the modern sovereign state.”

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

However, they add, between 2008 and 2009, Italy negotiated “a new definition of the frontiers with Austria, France and Switzerland.”

Due to global warming and and shrinking Alpine glaciers, the watershed—which determines large stretches of the borders between these countries—has shifted consistently. A new concept of movable border has thus been introduced into national legislation, recognizing the volatility of any watershed geography through regular alterations of the physical benchmarks that determine the exact frontier.

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

The actual project that resulted from this falls somewhere between landscape surveying and technical invention—and is a pretty awesome example of where territorial management, technological databases, and national archives all intersect:

On May 4th, 2014, the Italian Limes team installed a network of solar-powered GPS units on the surface of the Similaun glacier, following a 1-km-long section of the border between Italy and Austria, in order to monitor the movements of the ice sheet throughout the duration of the exhibition at the Corderie dell’Arsenale. The geographic coordinates collected by the sensors are broadcasted and stored every hour on a remote server via a satellite connection. An automated drawing machine—controlled by an Arduino board and programmed with Processing—has been specifically designed to translated the coordinates received from the sensors into a real-time representation of the shifts in the border. The drawing machine operates automatically and can be activated on request by every visitor, who can collect a customized and unique map of the border between Italy and Austria, produced on the exact moment of his [or her] visit to the exhibition.

The drawing machine, together with the altered maps and images it produces, are thus meant to reveal “how the Alps have been a constant laboratory for technological experimentation, and how the border is a compex system in evolution, whose physical manifestation coincides with the terms of its representation.”

The digital broadcast stations mounted along the border region are not entirely unlike Switzerland’s own topographic markers, over 7,000 “small historical monuments” that mark the edge of the country’s own legal districts, and also comparable to the pillars or obelisks that mark parts of the U.S./Mexico border. Which is not surprising: mapping and measuring border is always a tricky thing, and leaving physical objects behind to mark the route is simply one of the most obvious techniques.

As the next sequence of images shows, these antenna-like sentinels stand alone in the middle of vast ice fields, silently recording the size and shape of a nation.

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

The project, including topographic models, photographs, and examples of the drawing machine network, will be on display in the Italian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale until November 23, 2014. Check out their website for more.

Meanwhile, the research and writing that went into Glacier, Island, Storm remains both interesting and relevant today, if you’re looking for something to click through. Start here, here, or even here.

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

Italian Limes is a project by Folder (Marco Ferrari, Elisa Pasqual) with Pietro Leoni (interaction design), Delfino Sisto Legnani (photography), Dawid Górny, Alex Rothera, Angelo Semeraro (projection mapping), Claudia Mainardi, Alessandro Mason (team).

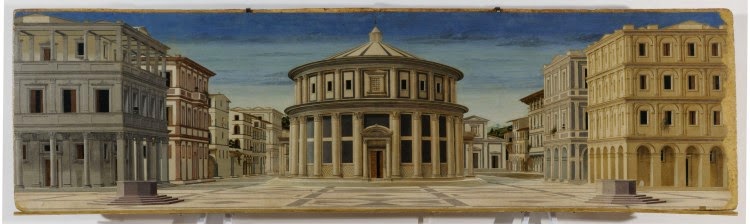

[Image: A perspectival representation of the “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: A perspectival representation of the “ideal city,” artist unknown]. [Image: Jeff Bezos as perspectival historian. Courtesy of

[Image: Jeff Bezos as perspectival historian. Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: One of several perspectival objects—contraptions for producing spatially accurate drawings—by Albrecht Dürer].

[Image: One of several perspectival objects—contraptions for producing spatially accurate drawings—by Albrecht Dürer]. [Image: Another “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: Another “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: From Etienne-Gaspard Robertson’s 1834 study of technical phantasmagoria, via

[Image: From Etienne-Gaspard Robertson’s 1834 study of technical phantasmagoria, via  [Image: A “moving face” transmitted by John Logie Baird at a public demonstration of TV in 1926 (photo

[Image: A “moving face” transmitted by John Logie Baird at a public demonstration of TV in 1926 (photo  [Image: Kristian Birkeland stares deeply into his universal simulator (

[Image: Kristian Birkeland stares deeply into his universal simulator ( [Image: From Birkeland’s The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition 1902-1903, Vol. 1: On the Cause of Magnetic Storms and The Origin of Terrestrial Magnetism (

[Image: From Birkeland’s The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition 1902-1903, Vol. 1: On the Cause of Magnetic Storms and The Origin of Terrestrial Magnetism ( [Image: Cropping in on the pic seen above (

[Image: Cropping in on the pic seen above (

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: The new plastic geology, photographed by

[Image: The new plastic geology, photographed by

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914].

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914]. [Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via

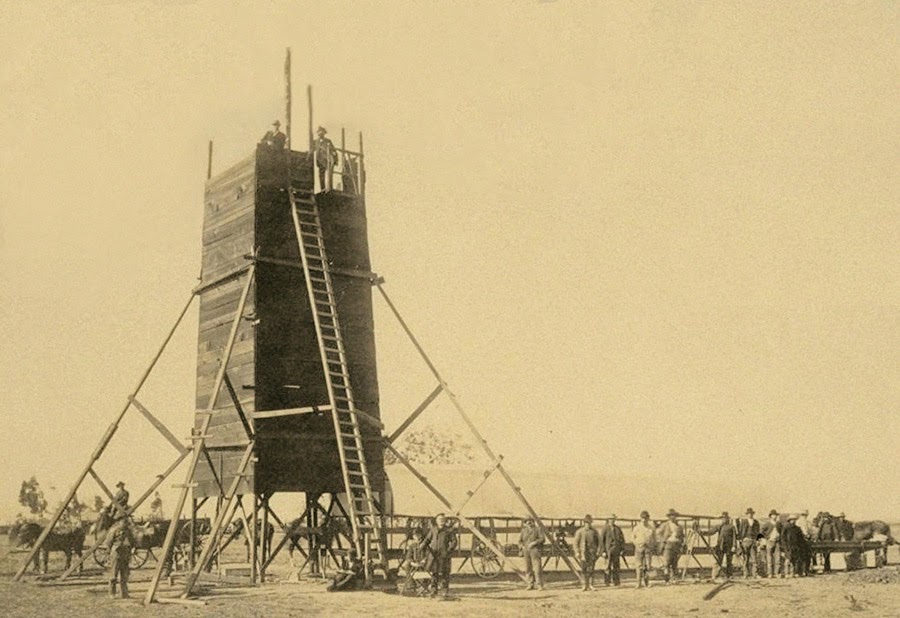

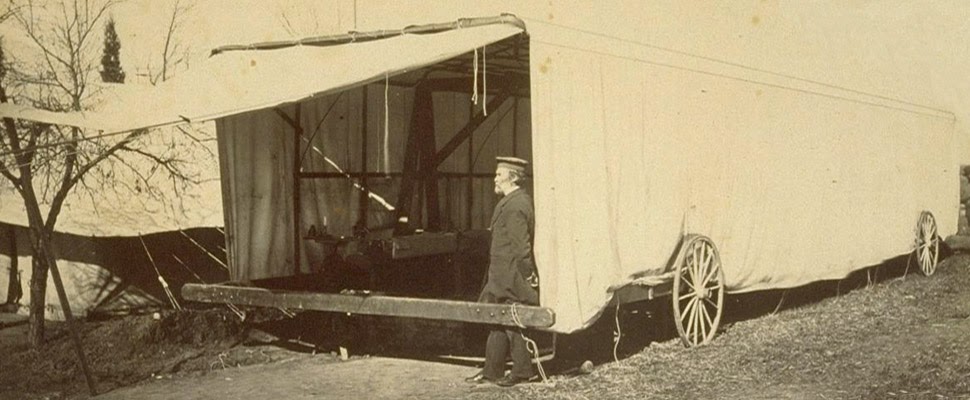

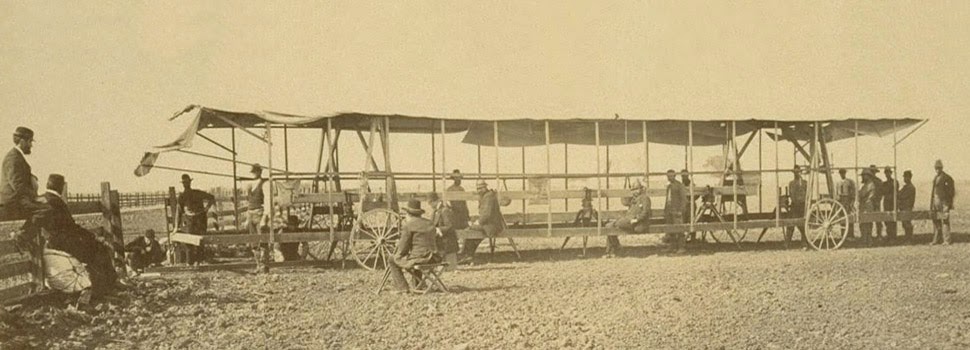

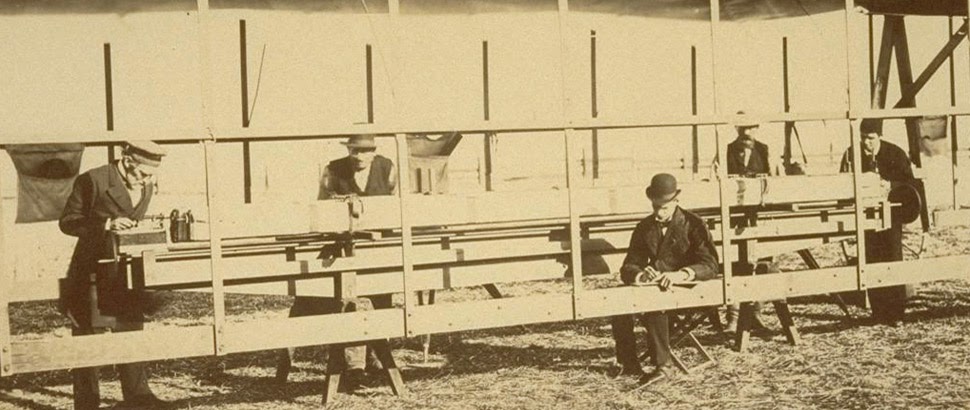

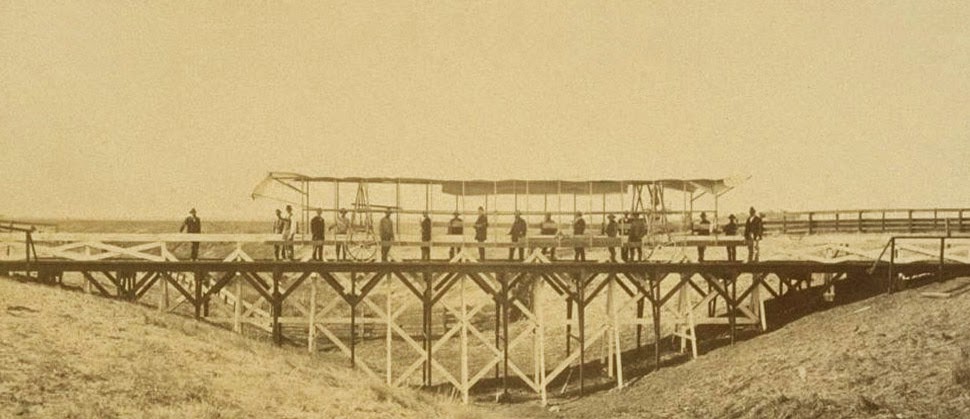

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.  The “moveable tent or ‘

The “moveable tent or ‘ The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the  In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.  That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land. Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called  [Image: The

[Image: The