[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office].

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office].

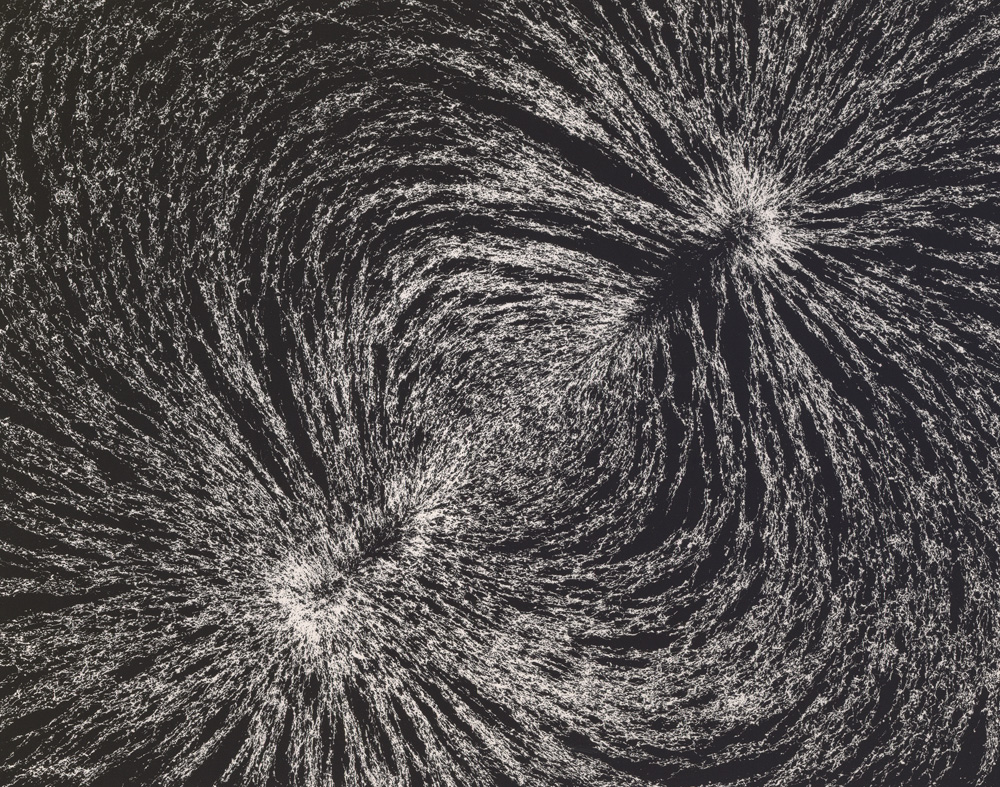

The technical systems by which autonomous, self-driving vehicles will safely navigate city streets are usually presented as some combination of real-time scanning and detailed mnemonic map or virtual reference model created for that vehicle.

As Alexis Madrigal has written for The Atlantic, autonomous vehicles are, in essence, always driving within a virtual world—like Freudian machines, they are forever unable to venture outside a sphere of their own projections:

The key to Google’s success has been that these cars aren’t forced to process an entire scene from scratch. Instead, their teams travel and map each road that the car will travel. And these are not any old maps. They are not even the rich, road-logic-filled maps of consumer-grade Google Maps.

They’re probably best thought of as ultra-precise digitizations of the physical world, all the way down to tiny details like the position and height of every single curb. A normal digital map would show a road intersection; these maps would have a precision measured in inches.

The vehicle can thus respond to the city insofar as its own spatial expectations are never sufficiently contradicted by the evidence at hand: if the city, as scanned by the vehicle’s array of sensors and instruments, corresponds to the vehicle’s own internal expectations, then it can make the next rational decision (to turn a corner, stop at an intersection, wait for a passing train, etc.).

However, I was very interested to see that an MIT research team led by Byron Stanley had applied for a patent last autumn that would allow autonomous vehicles to guide themselves using ground-penetrating radar. It is the subterranean realm that they would thus be peering into, in addition to the plein air universe of curb heights and Yield signs, reading the underworld for its own peculiar landmarks.

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office].

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office].

How would it work? Imagine, the MIT team suggests, that your autonomous vehicle is either in a landscape blanketed in snow. It is volumetrically deformed by all that extra mass and thus robbed not only of accurate points of measurement but also of any, if not all, computer-recognizable landmarks. Or, he adds, imagine that you have passed into a “GPS-denied area.”

In either case, you and your self-driving vehicle run the very real risk of falling off the map altogether, stuck in a machine that cannot find its way forward and, for all intents and purposes, can no longer even tell road from landscape.

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office].

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office].

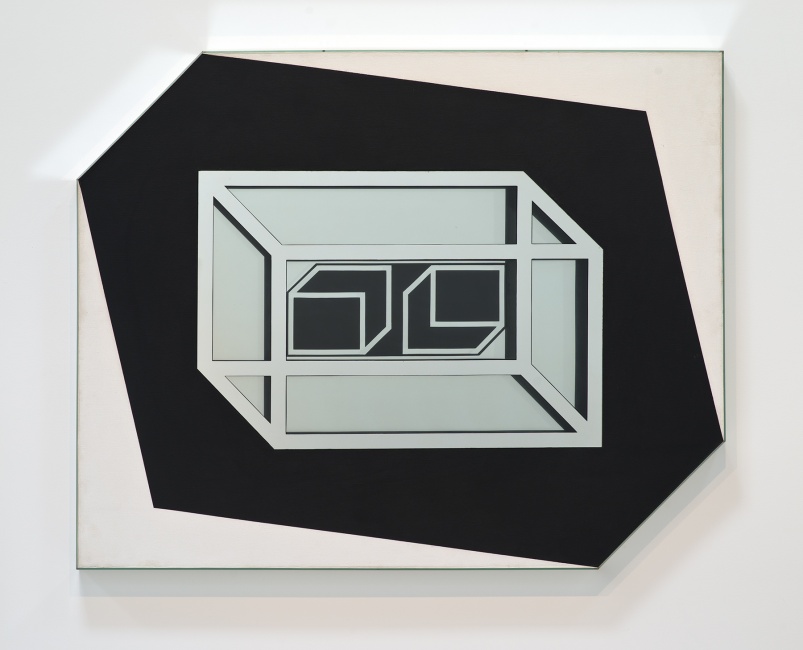

Stanley’s group has thus come up with the interesting suggestion that you could simply give autonomous vehicles the ability to see through the earth’s surface and scan for recognizable systems of pipework or other urban infrastructure down below. Your vehicle could then just follow those systems through the obscuring layers of rain, snow, or even tumbleweed to its eventual destination.

These would be cars attuned to the “subsurface region,” as the patent describes it, falling somewhere between urban archaeology and speleo-cartography.

In fact, with only the slightest tweaking of this technology and you could easily imagine a scenario in which your vehicle would more or less seek out and follow archaeological features in the ground. Picture something like an enormous basement in Rome or central London—or perhaps a strange variation on the city built entirely for autonomous vehicles at the University of Michigan. It is a vast expanse of concrete built—with great controversy—over an ancient site of incredible archaeological richness.

Climbing into a small autonomous vehicle, however, and avidly referring to the interactive menu presented on a touchscreen dashboard, you feel the vehicle begin to move, inching forward into the empty room. The trick is that it is navigating according to the remnant outlines of lost foundations and buried structures hidden in the ground around you, like a boat passing over shipwrecks hidden in the still but murky water.

The vehicle shifts and turns, hovers and circles back again, outlining where buildings once stood. It is acting out a kind of invisible architecture of the city, where its routes are not roads at all but the floor plans of old buildings and, rather than streets or parking lots, you circulate through and pause within forgotten rooms buried in the ground somewhere below.

In this “subsurface region” that only your vehicle’s radar eyes can see, your car finds navigational clarity, calmly poking along the secret forms of the city.

In any case, for more on the MIT patent, check out the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

(Via New Scientist).

[Image: Cropped Apollo mission panorama, courtesy Lunar and Planetary Institute, via @Rainmaker1973; view full].

[Image: Cropped Apollo mission panorama, courtesy Lunar and Planetary Institute, via @Rainmaker1973; view full]. [Image: “Discarded Christmas trees were used to help rebuild the sand dunes around three years ago,” writes

[Image: “Discarded Christmas trees were used to help rebuild the sand dunes around three years ago,” writes  [Image: The Christmas trees at Formby; photo courtesy

[Image: The Christmas trees at Formby; photo courtesy  [Image: The artificially stabilized beaches at Formby, with no sign of the displaced forest lurking below;

[Image: The artificially stabilized beaches at Formby, with no sign of the displaced forest lurking below;  [Image: A 17th-century engraving by Abraham Bosse, scanned from the excellent

[Image: A 17th-century engraving by Abraham Bosse, scanned from the excellent

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

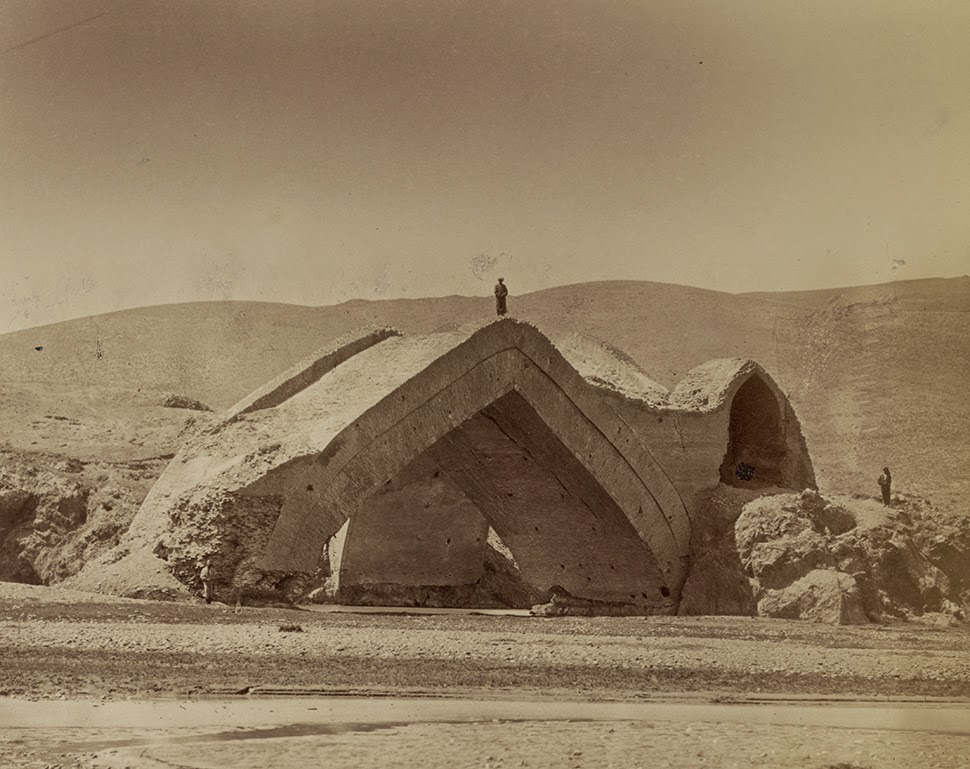

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;

[Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy  [Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy  [Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

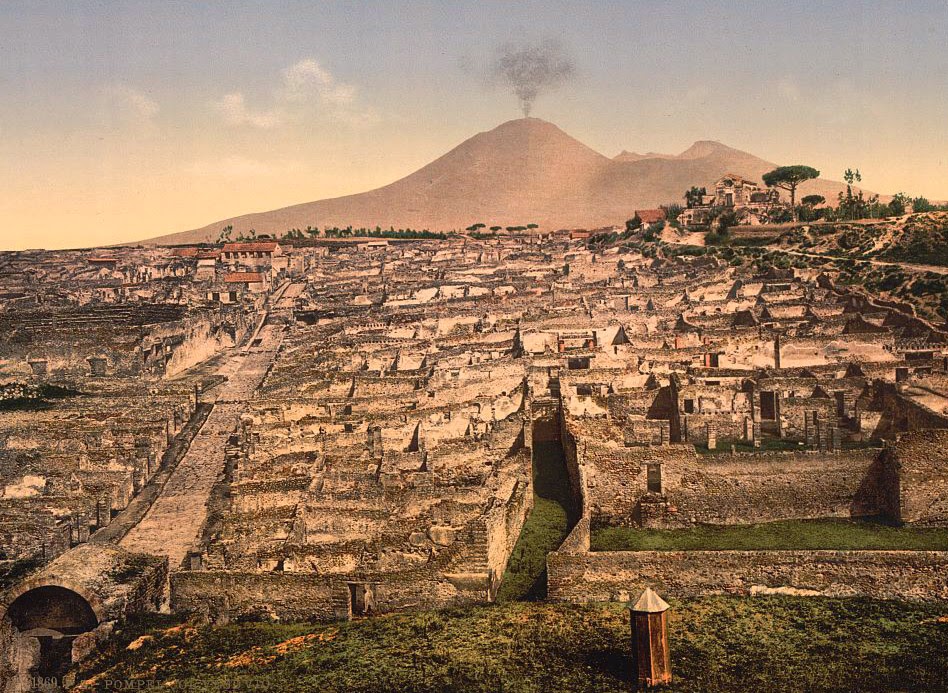

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy

[Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy  [Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of