[Image: Auguste Choisy].

[Image: Auguste Choisy].

France is considering a ban on stereoscopic viewing equipment—i.e. 3D films and game environments—for children, due to “the possible [negative] effect of 3D viewing on the developing visual system.”

As a new paper suggests, the use of these representational technologies is “not recommended for chidren under the age of six” and only “in moderation for those under the age of 13.”

There is very little evidence to back up the ban, however. As Martin Banks, a professor of vision science at UC Berkeley, points out in a short piece for New Scientist, “there is no published research, new or old, showing evidence of adverse effects from watching 3D content other than the short-term discomfort that can be experienced by children and adults alike. Despite several years of people viewing 3D content, there are no reports of long-term adverse effects at any age. On that basis alone, it seems rash to recommend these age-related bans and restrictions.”

Nonetheless, he adds, there is be a slight possibility that 3D technologies could have undesirable neuro-physical effects on infants:

The human visual system changes significantly during infancy, particularly the brain circuits that are intimately involved in perceiving the enhanced depth associated with 3D viewing technology. Development of this system slows during early childhood, but it is still changing in subtle ways into adolescence. What’s more, the visual experience an infant or young child receives affects the development of binocular circuits. These observations mean that there should be careful monitoring of how the new technology affects young children.

But not necessarily an outright ban.

In other words, overly early—or quantitatively excessive—exposure to artificially 3-dimensional objects and environments could be limiting the development of retinal strength and neural circuitry in infants. But no one is actually sure.

What’s interesting about this for me—and what simultaneously inspires a skeptical reaction to the supposed risks involved—is that we are already surrounded by immersive and complexly 3-dimensional spatial environments, built landscapes often complicated by radically diverse and confusing focal lengths. We just call it architecture.

Should the experience of disorienting works of architecture be limited for children under a certain age?

[Image: Another great image by Auguste Choisy].

[Image: Another great image by Auguste Choisy].

It’s not hard to imagine taking this proposed ban to its logical conclusion, claiming that certain 3-dimensionally challenging works of architectural space should not be experienced by children younger than a certain age.

Taking a cue from roller coasters and other amusement park rides considered unsuitable for people with heart conditions, buildings might come with warning signs: Children under the age of six are not neurologically equipped to experience the following sequence of rooms. Parents are advised to prevent their entry.

It’s fascinating to think that, due to the potential neurological effects of the built environment, whole styles of architecture might have to be reserved for older visitors, like an X-rated film. You’re not old enough yet, the guard says patronizingly, worried that certain aspects of the building will literally blow your mind.

Think of it as a Schedule 1 controlled space.

[Image: From the Circle of Francesco Galli Bibiena, “A Capriccio of an Elaborately Decorated Palace Interior with Figures Banqueting, The Cornices Showing Scenes from Mythology,” courtest of Sotheby’s].

[Image: From the Circle of Francesco Galli Bibiena, “A Capriccio of an Elaborately Decorated Palace Interior with Figures Banqueting, The Cornices Showing Scenes from Mythology,” courtest of Sotheby’s].

Or maybe this means that architecture could be turned into something like a new training regimen, as if you must graduate up a level before you are able to handle specific architectural combinations, like conflicting lines of perspective, unreal implications of depth, disorienting shadowplay, delayed echoes, anamorphic reflections, and other psychologically destabilizing spatial experiences.

Like some weird coming-of-age ceremony developed by a Baroque secret society overly influenced by science fiction, interested mentors watch every second as you and other trainees react to a specific sequence of architectural spaces, waiting to see which room—which hallway, which courtyard, which architectural detail—makes you crack.

Gifted with a finely honed sense of balance, however, you progress through them all—only to learn at the end that there are four further buildings, structures designed and assembled in complete secrecy, that only fifteen people on earth have ever experienced. Of those fifteen, three suffered attacks of amnesia within a year.

Those buildings’ locations are never divulged and you are never told what to prepare for inside of them—what it is about their rooms that makes them so neurologically complex—but you are advised to study nothing but optical illusions for the next six months.

[Image: One more by Auguste Choisy].

[Image: One more by Auguste Choisy].

Of course, you’re told, if it ever becomes too much, you can simply look away, forcing yourself to focus on only one detail at a time before opening yourself back up to the surrounding spatial confusion.

After all, as Banks writes in New Scientist, the discomfort caused by one’s first exposure to 3D-viewing technology simply “dissipates when you stop viewing 3D content. Interestingly, the discomfort is known to be greater in adolescents and young adults than in middle-aged and elderly adults.”

So what do you think—could (or should?) certain works of architecture ever be banned for neurologically damaging children under a certain age? Is there any evidence that spatially disorienting children’s rooms or cribs have the same effect as 3D glasses?

[Image: “Historical Monument of the American Republic” by Erastus Salisbury Field].

[Image: “Historical Monument of the American Republic” by Erastus Salisbury Field].

[Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Images: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Images: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy  [Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Image: Bond Street platform tunnels, courtesy

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Another great image by

[Image: Another great image by  [Image: From the Circle of Francesco Galli Bibiena, “A Capriccio of an Elaborately Decorated Palace Interior with Figures Banqueting, The Cornices Showing Scenes from Mythology,” courtest of

[Image: From the Circle of Francesco Galli Bibiena, “A Capriccio of an Elaborately Decorated Palace Interior with Figures Banqueting, The Cornices Showing Scenes from Mythology,” courtest of  [Image: One more by

[Image: One more by

[Image: The International Space Station at night, photographed by astronaut

[Image: The International Space Station at night, photographed by astronaut  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by astronaut

[Images: Photos by astronaut  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

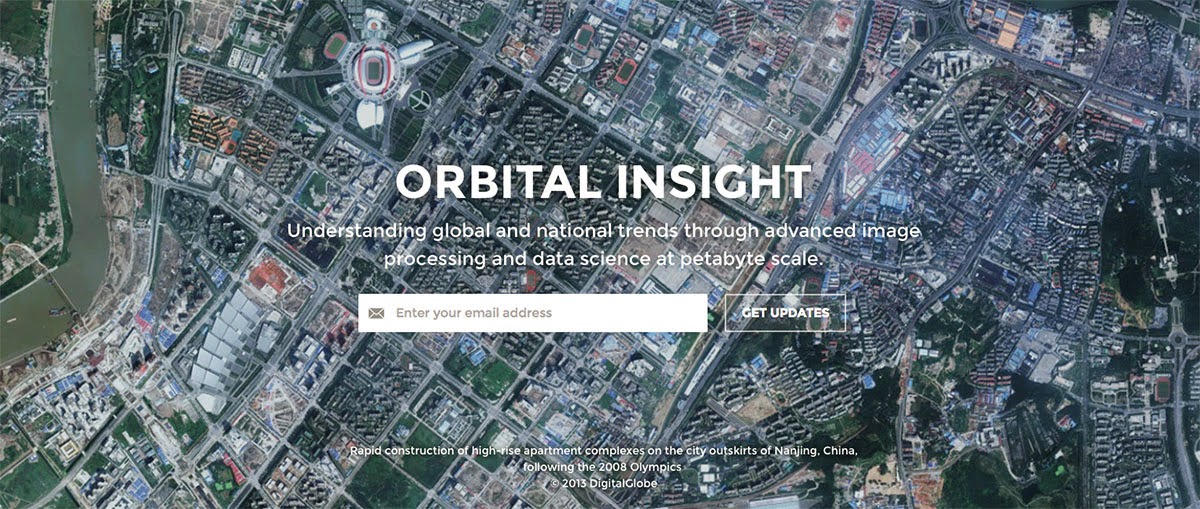

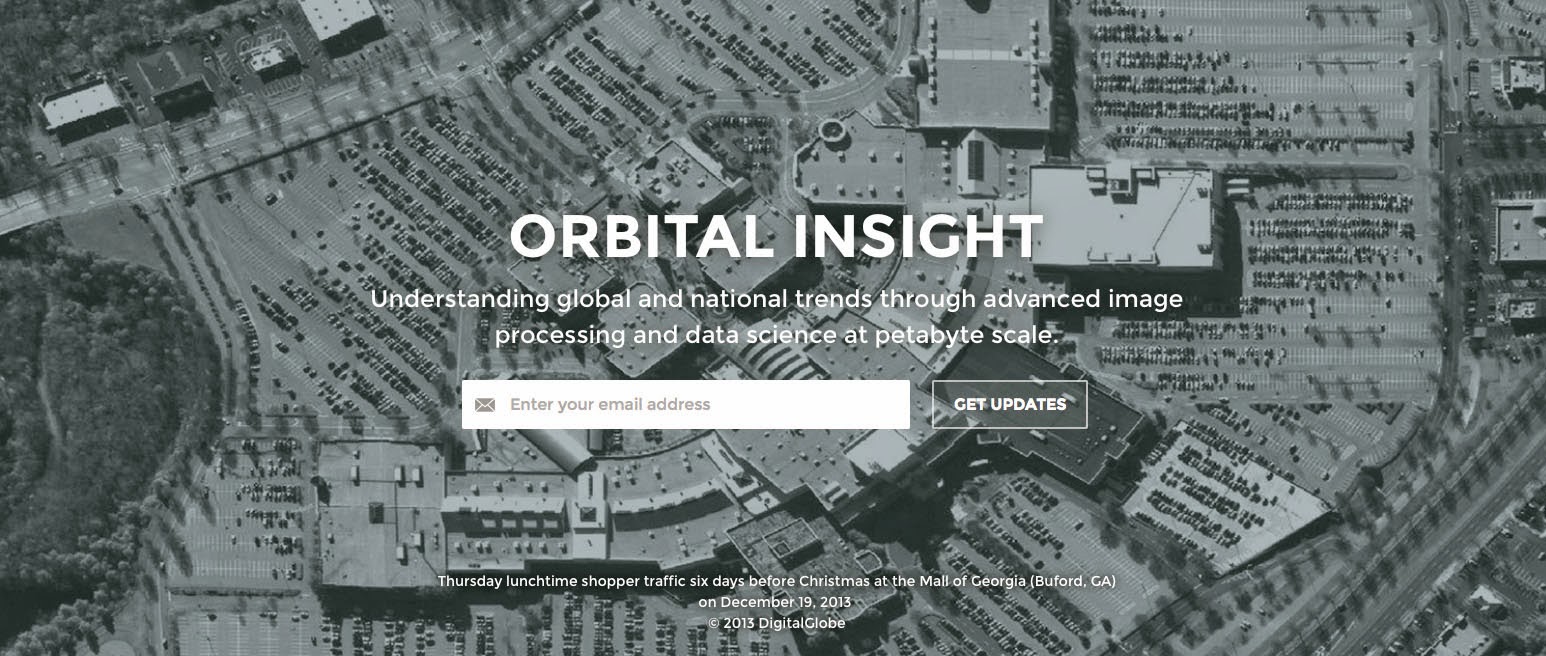

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of  [Image: A screen grab from the homepage of

[Image: A screen grab from the homepage of

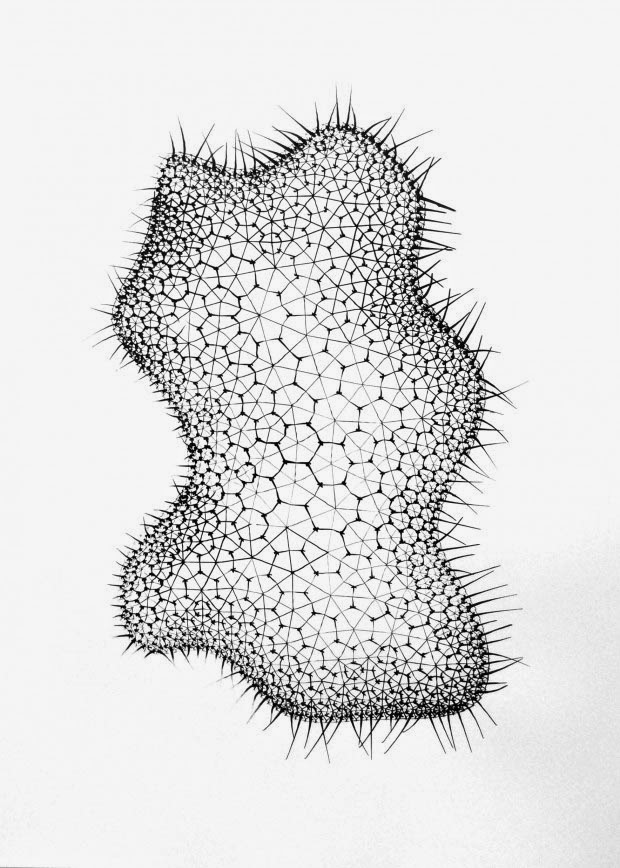

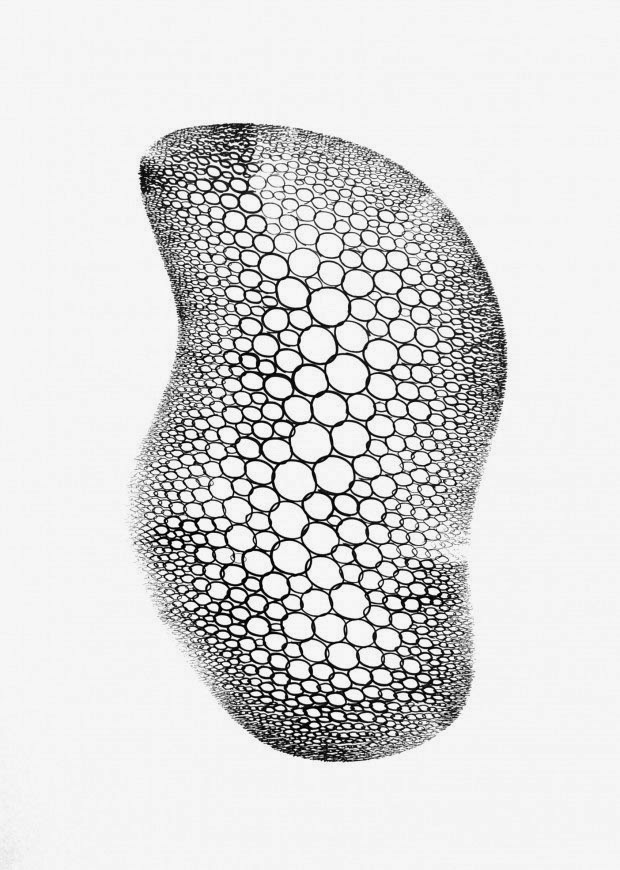

[Image: “Untitled #13,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #13,” from “ [Image: The robot at work, from “

[Image: The robot at work, from “ [Image: “Untitled #16,” from “

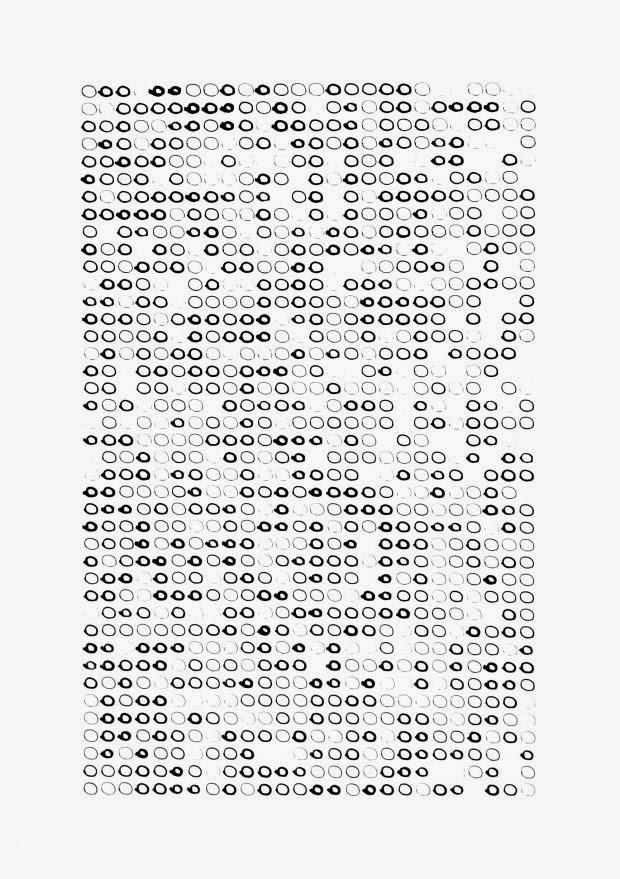

[Image: “Untitled #16,” from “ [Image: “Untitled #6 (1066 Circles each Drawn at Different Pressures at 50mm/s),” from “

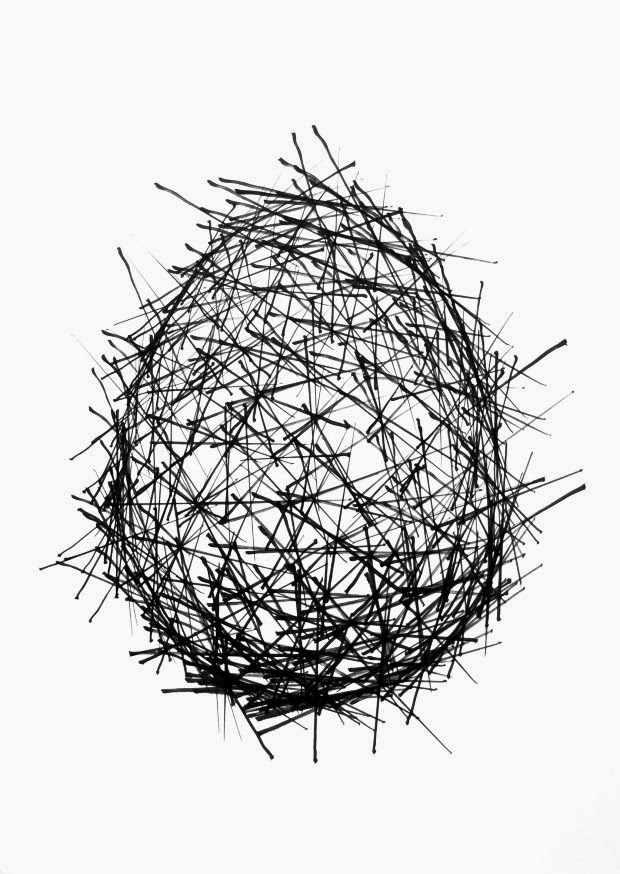

[Image: “Untitled #6 (1066 Circles each Drawn at Different Pressures at 50mm/s),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #7 (1066 Lines Drawn between Random Points in a Grid),” from “

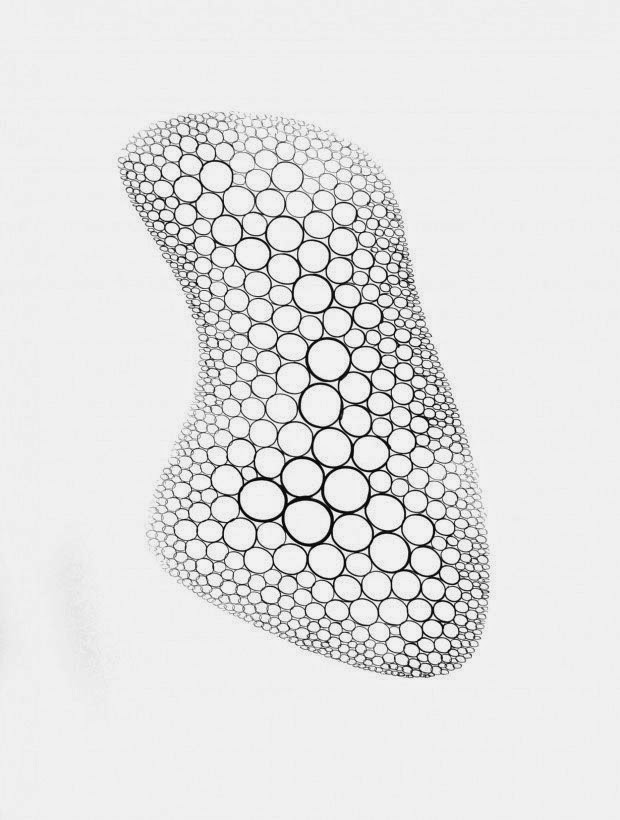

[Image: “Untitled #7 (1066 Lines Drawn between Random Points in a Grid),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #15 (Twenty Seven Nodes with Arcs Emerging from Each),” from “

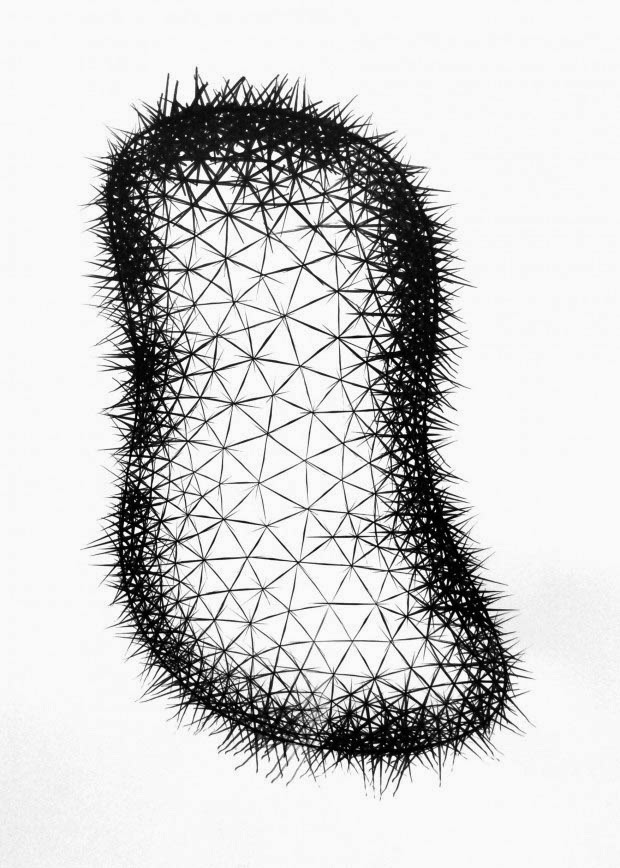

[Image: “Untitled #15 (Twenty Seven Nodes with Arcs Emerging from Each),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #3 (Extended Lines Drawn from 300 Points on an Ovoid to 3 Closest Neigh[bor]ing Points at 100mm/s)” (2014) from “

[Image: “Untitled #3 (Extended Lines Drawn from 300 Points on an Ovoid to 3 Closest Neigh[bor]ing Points at 100mm/s)” (2014) from “ [Image: “Untitled #12,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #12,” from “ [Image: “Untitled #14,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #14,” from “

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via

[Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From a private collection of failed safes, vault walls, and other crime scene evidence; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: From a private collection of failed safes, vault walls, and other crime scene evidence; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: From

[Image: From