For a variety of reasons, I was recently looking at a May 2011 report from the Air Force Research Laboratory on “Robotics: Research and Development.”

[Image: From an Air Force Research Laboratory presentation on “Robotics: Research and Development”].

[Image: From an Air Force Research Laboratory presentation on “Robotics: Research and Development”].

There—amidst plans for unmanned robotic ground convoys and autonomous perimeter defense systems for future bases and cities, not to mention fleets of robotic bulldozers field-tested for use in mine-clearance operations—there was one slide about something called “counter tunnel robotics.”

Being obsessed with all things underground, this immediately caught my eye—especially as this is a program whose goal is to “develop an unmanned system with the capability to access, traverse, navigate, map, survey, and disrupt operations in rough subterranean environments.” A “miniature mapping payload” is under development, one that will allow for accurate cartographic surveys of complex underground spaces; but, because current methods “will not work in the more challenging (non-planar) tunnel environments,” the Air Force explains, the new focus for R&D “will be on developing 3D mapping techniques using 3D sensors.”

From last month’s Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International—or AUVSI—conference in Washington D.C., where this technology was discussed in detail:

The [Counter Tunnel Robotics] system is an innovative all-terrain mobility platform capable of accessing tunnel systems through a small (8 inch) borehole and traversing adverse tunnel terrain including vertical obstacles up to 2ft in height and chasms up to 2ft in length. The system’s function is to provide a platform capable of carrying a small sensor package while navigating and overcoming terrain obstacles inside the tunnel. Counter tunnel technologies are needed to support intelligence gathering and safety of troops and personnel in unmapped and unknown tunnel environments. The system is the initial step in achieving a fully autonomous counter tunnel system.

A few things worth pointing out here include the mind-boggling image of “a fully autonomous counter tunnel system” operating on its own somewhere inside the earth’s surface, like something out of a Jonathan Lethem novel, surely fueling the imaginations of scifi screenplay writers the world over—a planet infested with artificially intelligent tunneling machines. But it is also worth noting that these systems will very likely not be confined to use on—or in—the earth. In fact, autonomous tunnel-exploration robots will find a very hearty market for themselves exploring caves on the moon, on Mars, on asteroids, and perhaps elsewhere, in a fairly clear-cut example of military research finding a productive home for itself in other contexts.

However, I also want to mention how fascinating it is to see that the Air Force Research Laboratory is involved in this, as it actually penetrates the surface of the earth and is very much a project of the ground. It is a landscape project. But the implication here is that these autonomous spelunking units are perhaps seen as a new type of ordnance—that is, they are intelligent bombs that don’t explode so much as explore. They are artillery and surveillance rolled into one. Imagine a bomb that doesn’t destroy a building: instead, it drops into that building and proceeds to map every room and hallway.

But, much more interestingly, there is perhaps also an indication here that a conceptual revolution is underway within the Air Force, where the earth itself—geological space—is seen as merely a thicker version of the sky. That is, the ground is now seen by Air Force strategists as an abstract, three-dimensional space through which machines can operate, like planes in the sky, navigating past “terrain obstacles” like so much turbulence. In a sense, the inside of the earth becomes ontologically—and, certainly, technically—identical to the atmosphere: it is an undifferentiated space that can be traversed in all directions by the appropriate machinery.

Flying and tunneling thus become elided, revealed as one and the same activity; and the Air Force is understandably now in the business of the underground.

[Image: “A U.S. Air Force F-22A Raptor Stealth Fighter Jet Executes A Maneuver Through A Cloud Of Vapor”—that is, it tunnels through the sky—”At The 42nd Naval Base Ventura County Air Show, April 1, 2007, Point Mugu, State of California, USA”; photo by Technical Sgt. Alex Koenig, United States Air Force; Courtesy of Defense Visual Information and the United States Department of Defense].

[Image: “A U.S. Air Force F-22A Raptor Stealth Fighter Jet Executes A Maneuver Through A Cloud Of Vapor”—that is, it tunnels through the sky—”At The 42nd Naval Base Ventura County Air Show, April 1, 2007, Point Mugu, State of California, USA”; photo by Technical Sgt. Alex Koenig, United States Air Force; Courtesy of Defense Visual Information and the United States Department of Defense].

That, of course, or it was simply an issue of the wrong office receiving research funds for this, and, next fiscal quarter, the Army dutifully takes over…

(For a bit more on underground military activity, see this older post on BLDGBLOG).

[Image: Possible cave entrance on Mars, via

[Image: Possible cave entrance on Mars, via

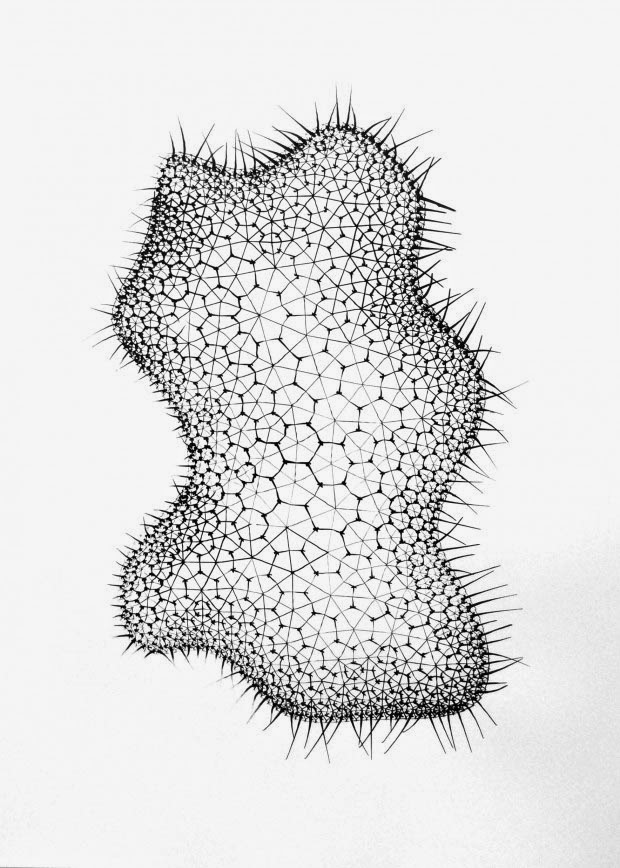

[Image: “Untitled #13,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #13,” from “ [Image: The robot at work, from “

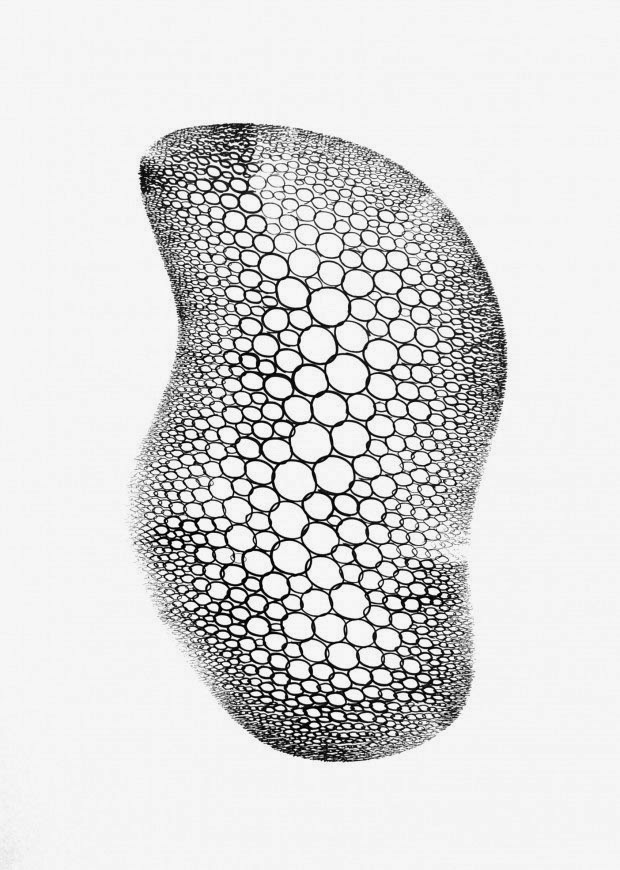

[Image: The robot at work, from “ [Image: “Untitled #16,” from “

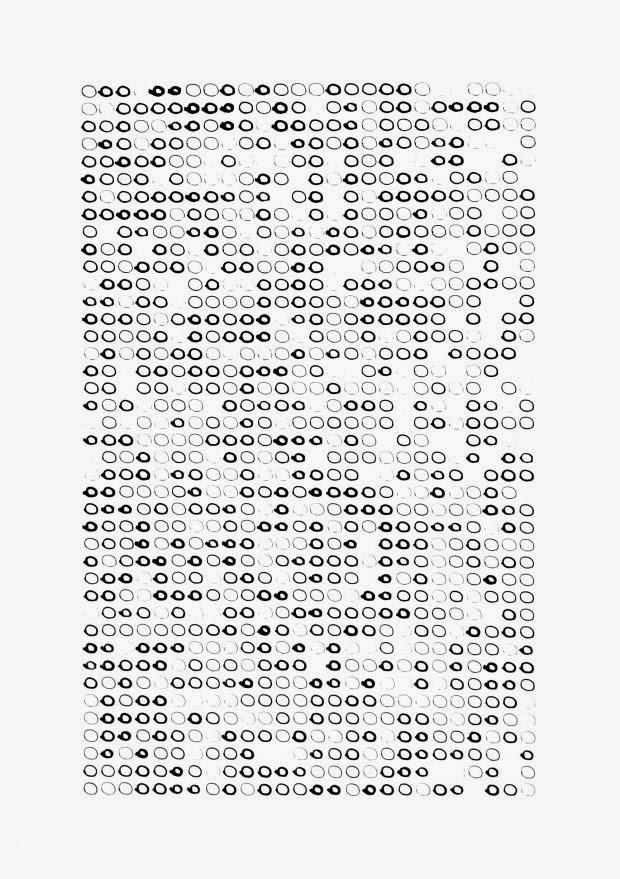

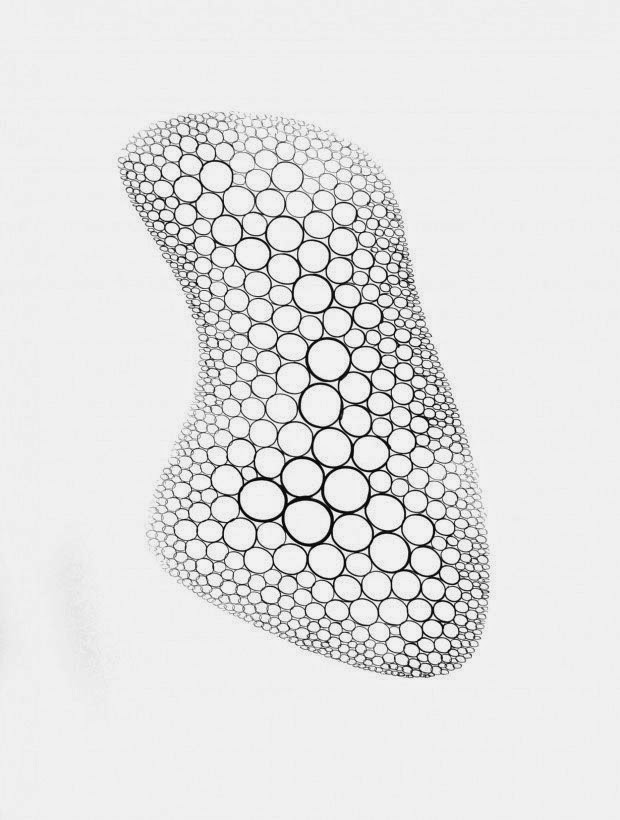

[Image: “Untitled #16,” from “ [Image: “Untitled #6 (1066 Circles each Drawn at Different Pressures at 50mm/s),” from “

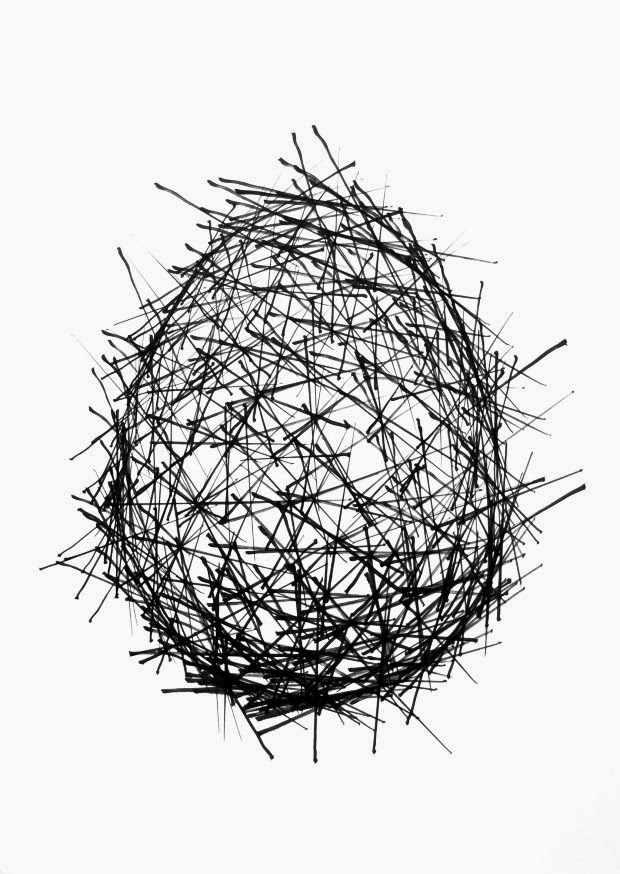

[Image: “Untitled #6 (1066 Circles each Drawn at Different Pressures at 50mm/s),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #7 (1066 Lines Drawn between Random Points in a Grid),” from “

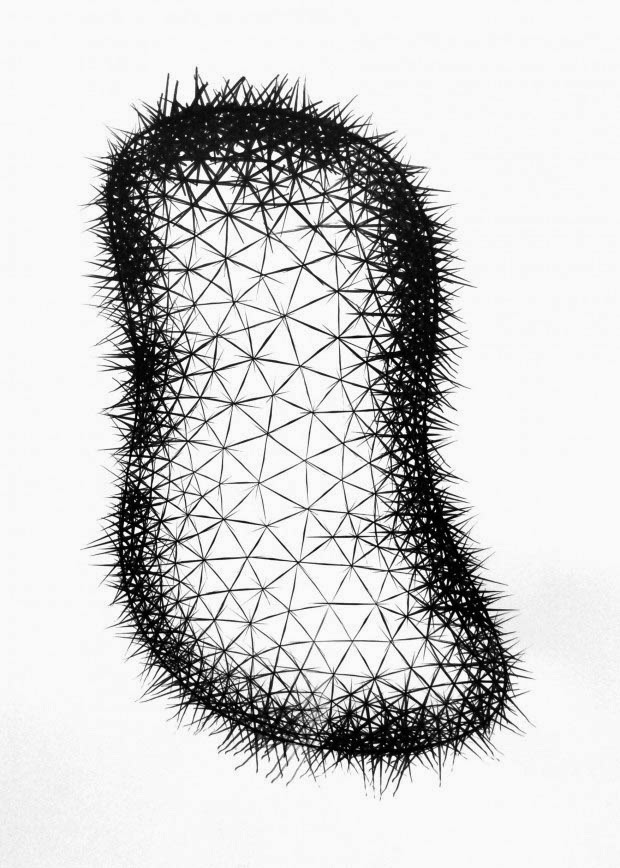

[Image: “Untitled #7 (1066 Lines Drawn between Random Points in a Grid),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #15 (Twenty Seven Nodes with Arcs Emerging from Each),” from “

[Image: “Untitled #15 (Twenty Seven Nodes with Arcs Emerging from Each),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #3 (Extended Lines Drawn from 300 Points on an Ovoid to 3 Closest Neigh[bor]ing Points at 100mm/s)” (2014) from “

[Image: “Untitled #3 (Extended Lines Drawn from 300 Points on an Ovoid to 3 Closest Neigh[bor]ing Points at 100mm/s)” (2014) from “ [Image: “Untitled #12,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #12,” from “ [Image: “Untitled #14,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #14,” from “

[Image: From an Air Force Research Laboratory presentation on “Robotics: Research and Development”].

[Image: From an Air Force Research Laboratory presentation on “Robotics: Research and Development”]. [Image: “A U.S. Air Force F-22A Raptor Stealth Fighter Jet Executes A Maneuver Through A Cloud Of Vapor”—that is, it tunnels through the sky—”At The 42nd Naval Base Ventura County Air Show, April 1, 2007, Point Mugu, State of California, USA”; photo by Technical Sgt. Alex Koenig,

[Image: “A U.S. Air Force F-22A Raptor Stealth Fighter Jet Executes A Maneuver Through A Cloud Of Vapor”—that is, it tunnels through the sky—”At The 42nd Naval Base Ventura County Air Show, April 1, 2007, Point Mugu, State of California, USA”; photo by Technical Sgt. Alex Koenig,