Ten years ago, this would have been a speculative design project by Sascha Pohflepp: “hyper-accumulating” plants are being used to concentrate, and thus “mine,” valuable metals from soil.

[Image: Nickel-rich sap; photo by Antony van der Ent, courtesy New York Times.]

[Image: Nickel-rich sap; photo by Antony van der Ent, courtesy New York Times.]

“With roots that act practically like magnets, these organisms—about 700 are known—flourish in metal-rich soils that make hundreds of thousands of other plant species flee or die,” the New York Times reported last week. “Slicing open one of these trees or running the leaves of its bush cousin through a peanut press produces a sap that oozes a neon blue-green. This ‘juice’ is actually one-quarter nickel, far more concentrated than the ore feeding the world’s nickel smelters.”

A while back, I went on a road-trip with Edible Geography to visit some maple syrup farms north of where we lived at the time, in New York City. The woods all around us were tubed together in a huge, tree-spanning network—“forest hydraulics,” as Edible Geography phrased it at the time—as the trees’ valuable liquid slowly flowed toward a pumping station in the center of the forest.

It was part labyrinth, part spiderweb, a kind of semi-automated tree-machine at odds with the image of nature with which most maple syrup is sold.

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

Imagining a similar landscape, but one designed as a kind of botanical mine—a forest accumulator, metallurgical druidry—is incredible.

And it’s not even a modern idea, as the New York Times points out. For all its apparent, 21st-century sci-fi, the idea of harvesting metal from plants is at least half a millennium old: “The father of modern mineral smelting, Georgius Agricola, saw this potential 500 years ago. He smelted plants in his free time. If you knew what to look for in a leaf, he wrote in the 16th century, you could deduce which metals lay in the ground below.”

This brings to mind an older post here about detection landscapes, or landscapes—yards, meadows, gardens, forests—deliberately planted with species that can indicate what is in the soil beneath them.

In the specific case of that post, this had archaeological value, allowing researchers to find abandoned Viking settlements in Greenland based on slight chemical changes that have affected which plants are able to thrive. Certain patches of flower, for example, act as archaeological indicator species, marking the locations of lost settlements.

In any case, my point is simply that vegetation can be read, or treated as a sign to be interpreted, whether by indicating the presence of archaeological ruins or by revealing the potential market-value of a site’s subterranean metal content.

Indeed, we read, “This vegetation could be the world’s most efficient, solar-powered mineral smelters,” with “the additional value of enabling areas with toxic soils to be made productive. Smallholding farmers could grow on metal-rich soils, and mining companies might use these plants to clean up their former mines and waste and even collect some revenue.” That is, you could filter and clean contaminated soils by drawing heavy-metal pollutants out of the ground, producing saps that are later harvested.

Fast-forward ten years: it’s 2030 and landscape architecture studios around the world are filled with speculative metal-harvesting plant designs—contaminated landscapes laced with gardens of hardy, sap-producing trees—even as industrial behemoths, like Rio Tinto and Barrick Gold, are breeding proprietary tree species in top-secret labs, genetically modifying them to maximize metal uptake.

Weird saps accumulate in iridescent lagoons. Autumn leaves glint, literally metallic, in the sun. Tiny metal capillaries weave up the trunks of black-wooded trees, in filigrees of gold and silver. The occasional forest fire smells not of smoke, but of copper and tin. Reclaimed timber, with knots and veins partially metallized, is used as luxury flooring in suburban homes.

Read more at the New York Times.

(Thanks to Wayne Chambliss for the tip!)

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

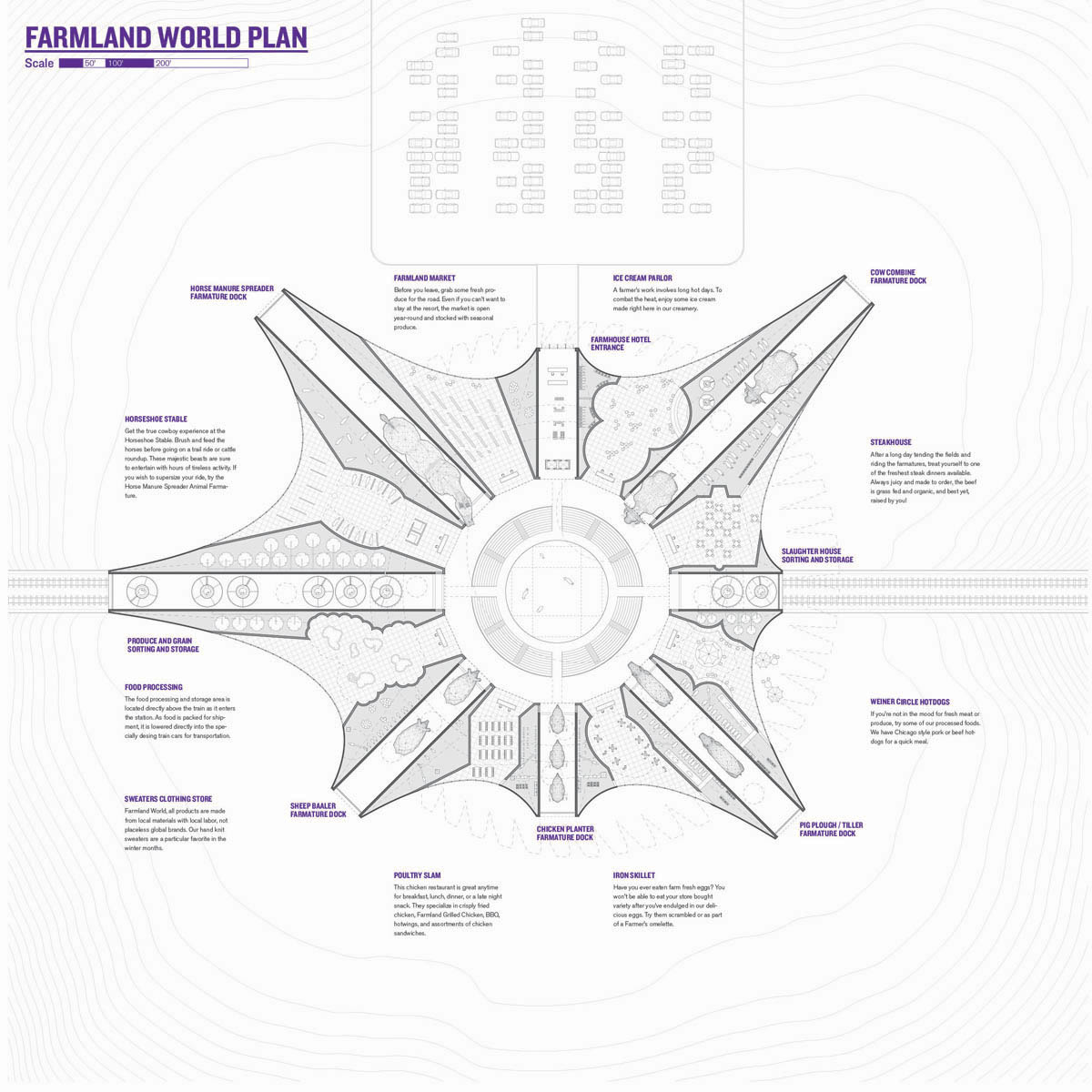

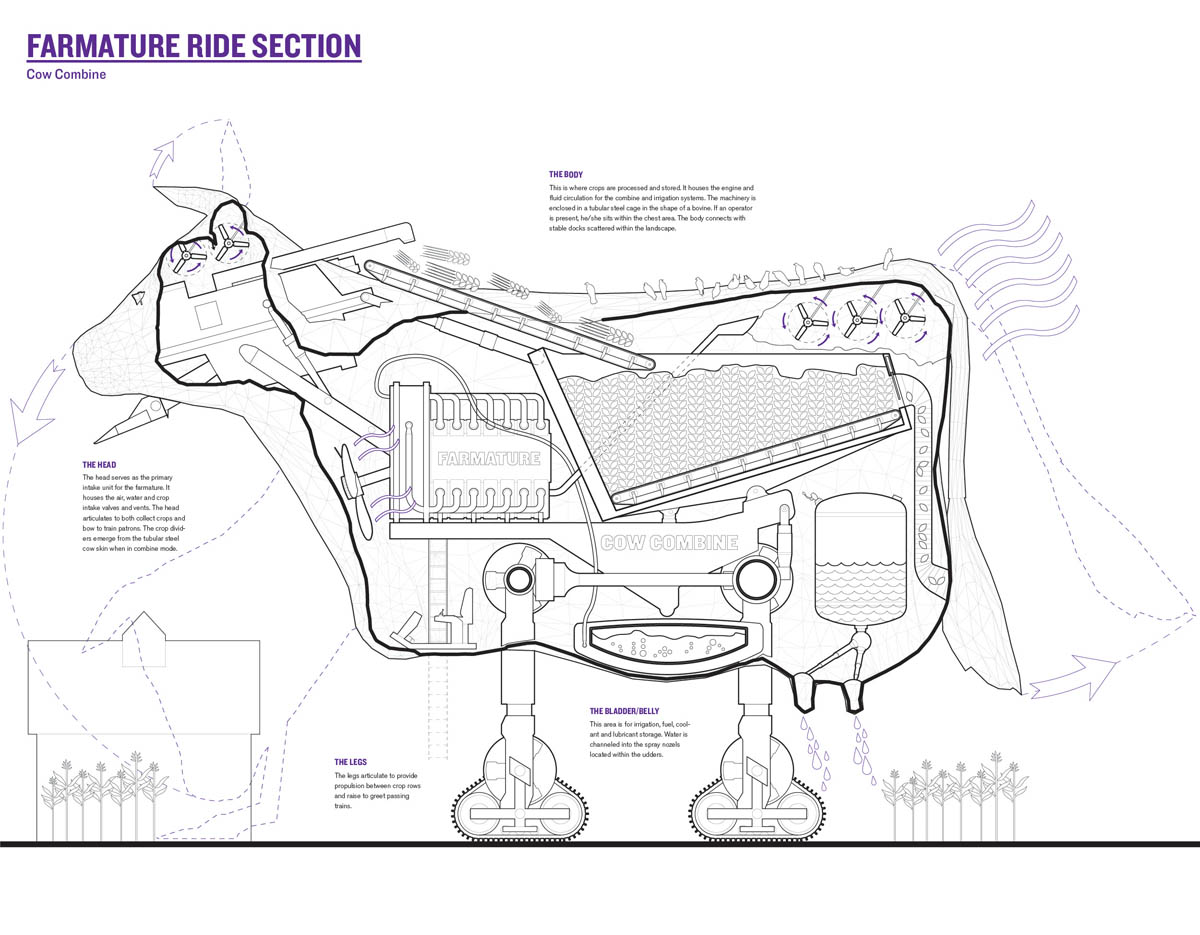

[Images: The robotic super-cows of “

[Images: The robotic super-cows of “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “