[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 2, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 2, 2007)” by David Maisel].

The following essay was previously published under the title “Infinite Exchange” in Black Maps by David Maisel (Steidl), as well as in Cabinet Magazine #50.

1.

In a 2011 paper on the medical effects of scurvy, author Jason C. Anthony offers a remarkable detail about human bodies and the long-term presence of wounds.

“Without vitamin C,” Anthony writes, “we cannot produce collagen, an essential component of bones, cartilage, tendons and other connective tissues. Collagen binds our wounds, but that binding is replaced continually throughout our lives. Thus in advanced scurvy”—reached when the body has gone too long without vitamin C—“old wounds long thought healed will magically, painfully reappear.”

In a sense, there is no such thing as healing. From paper cuts to surgical scars, our bodies are catalogues of wounds: imperfectly locked doors quietly waiting, sooner or later, to spring back open.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 5, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 5, 2007)” by David Maisel].

2.

The Carlin Trend was discovered in north-central Nevada, near the town of Elko, in 1962. Some fifty years later, at this time of writing, it remains one of the world’s largest actively mined deposits of gold ore. In fact, the region has become something of a category-maker in the gold industry today, which describes analogous landscapes and ore bodies as “Carlin-type” deposits. The Carlin Trend is a standard, in other words: a referent against which others are both literally and rhetorically measured.

The trend’s discovery and subsequent exploitation—and the extraordinary negative landforms that have resulted from its exhumation—has been a story of nineteenth-century U.S. mining laws, legally dubious provisions governing public land, extraction industry multinationals, advanced geological modeling software, specialty equipment few people can name let alone operate, and genetically modified bacteria mixed into vats of gold-harvesting slurry.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 1, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 1, 2007)” by David Maisel].

Writing in 1989, John Seabrook of The New Yorker pointed out that, in the previous eight years alone, more gold had been mined from the Carlin Trend “than came out of any of the bonanzas that feature so prominently in our national mythology, including the California bonanza of 1849.” That’s because gold in the region is all but ubiquitous, peppered and snaked throughout Nevada:

There is gold in the Battle Mountain Formation, the range that runs southeast of town; gold in the alluvium to the west; gold in the Black Rock Desert to the northwest; gold in the Sheep Creek Range and in the Tuscarora Mountains to the northeast. The Tuscaroras are especially rich. Along the Carlin Trend, a forty-mile stretch of this range, are twelve deposits. Some people believe that a much richer swatch of ore, a deposit to rival South Africa’s Gold Reef, runs unbroken under the Carlin Trend, perhaps three thousand feet down—more than three times as deep as the deepest mines there now go.

“Some people believe”: more is hidden in the apparent neutrality of Seabrook’s phrase than we might at first suspect. Mining for gold—the actual, violent excision of waste rock from the earth, searching for ore—is never a question of finding a perfect, shiny lump of solid metal and carefully, surgically removing it from the planet. Gold is diffuse. It is now more often mined as particles, not blocks or even nuggets. Like glitter, it is scattered throughout the rocks around it.

In fact, the presence of gold, in many cases, can only be inferred. The angle at which local rock strata dip back into the planet, the direction water flows through the landscape, or the complex of other minerals and crystals locked in the rocks underground: these all, to varying degrees, act as telltale signatures for the famously coy king of metals.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 18, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 18, 2007)” by David Maisel].

Looking for these signatures entails a peculiar mix of local folklore and verified science, and the hunt—sometimes life-consuming, sometimes maddening—for signs is exhaustively documented by what Seabrook calls “prospecting paraphernalia: geological reports, assay figures, maps, contracts, aerial photographs, electromagnetic surveys, gravitometer readings, lawsuits, letters from people who think they have gold on their property, letters from people who know people who have gold on their property.”

Gold is less discovered, we might say, than interpreted.

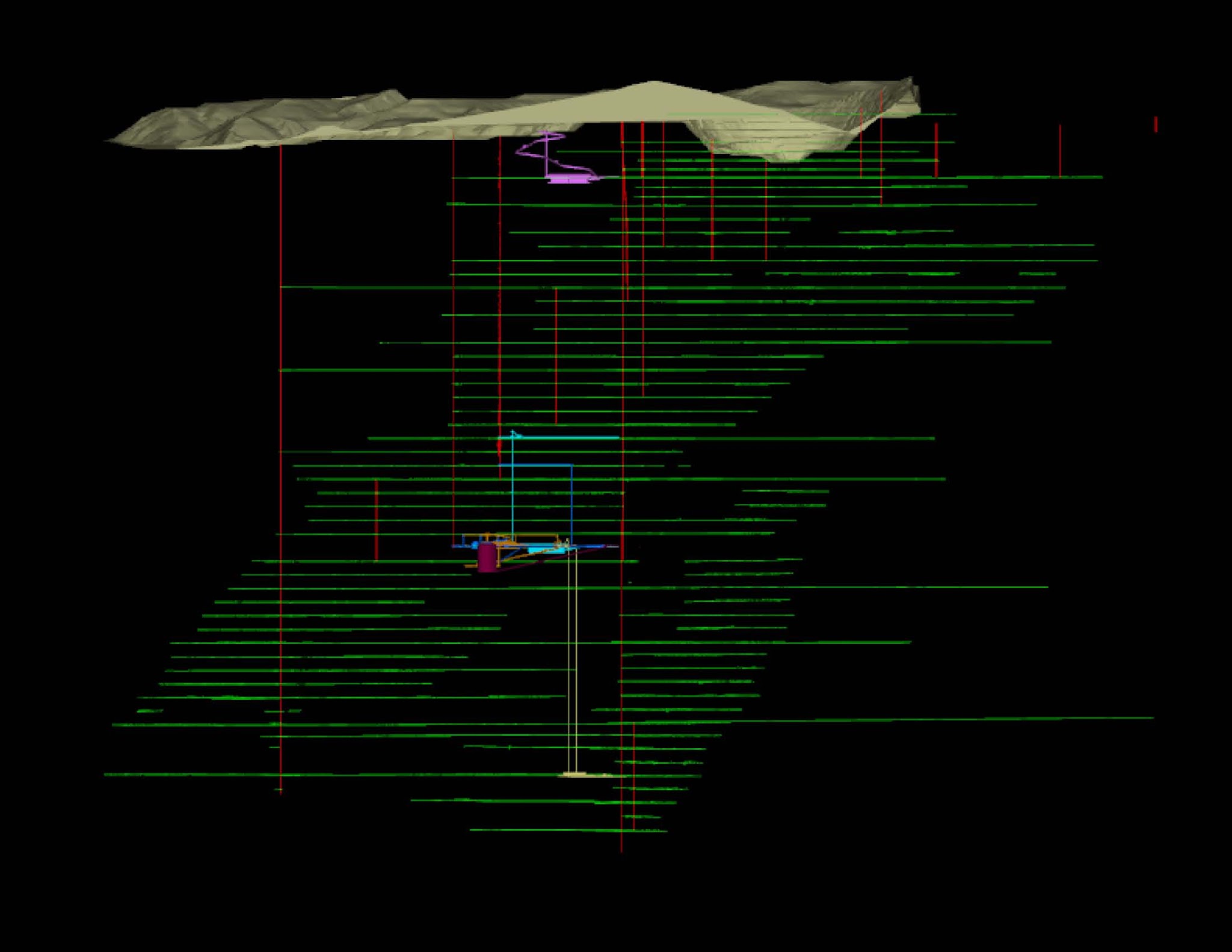

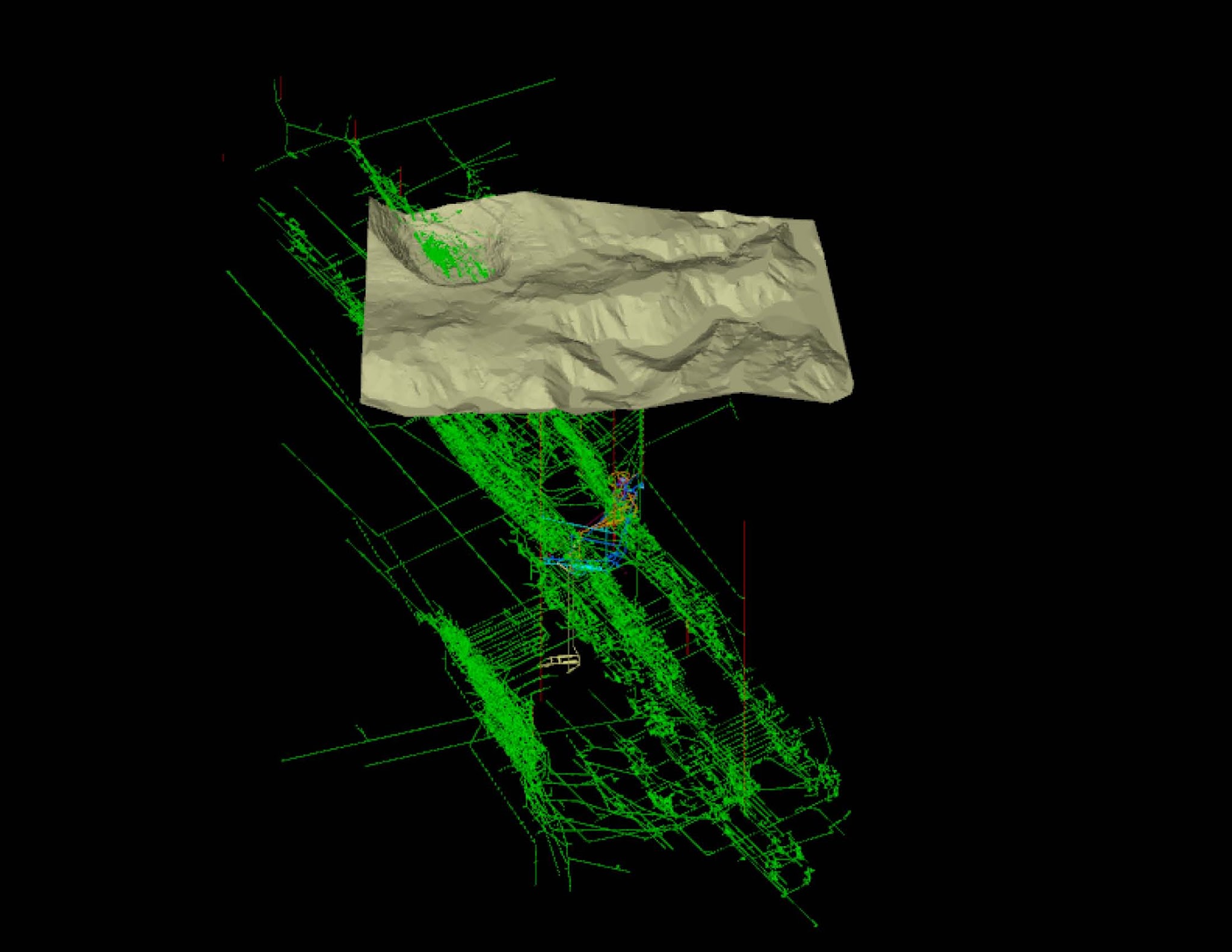

The Carlin Trend has thus served as a test site, now in its fifty-first year, for various interpretive techniques, both scientific and superstitious. Specialty journals refer to the region’s “geochemical patterns”—only fragments of which are available to them to analyze for “the characteristics, signatures, and genesis of Nevada’s world-class gold systems”—the idea being that these might be found again elsewhere and thus be more instantly recognizable. Geologists track concentrations, contours, “metal zones,” and mineralized fractures; they build models of “stacked geochemical anomalies” in the earth below, hoping to piece together an accurate model of the gold ore’s location.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 8, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 8, 2007)” by David Maisel].

Where the gold came from in the first place is yet another interpretive preoccupation. A paper—forthrightly titled “Is the Ancestral Yellowstone Hotspot Responsible for the Tertiary ‘Carlin’ Mineralization in the Great Basin of Nevada?”—suggests that the gold of the Carlin Trend is actually a thermal after-effect, or geochemical ghost, of the still-nomadic Yellowstone hotspot that once pulsed and geysered beneath Nevada.

The language used to describe these deposits is often extraordinary. We read, for instance, that discontinuous ore bodies apparently produced at different “stages of mineralization” in the earth’s history might, in fact, be “part of a single event that evolved chemically through time.” That is, one state-sized geological event—with titanic embryos merging and splitting inside the earth—delicately infused into the landscape from below as slow pulses of mineral-rich magmatic fluid freeze into spidery veins of precious metal. Or we read about “anomaly-related mineral assemblages,” millions of years’ worth of “mineralizing events,” and “geochemical halos in this part of the Carlin Trend.” Industrial descriptions of the earth’s interior lend an unexpected poetry to the act of mining.

Another way of saying all this is that mind-bogglingly large terrestrial events, occurring invisibly below ground in rock formations we can only measure indirectly—scanning the earth for hidden signatures—produce ore bodies, the excavation, dismemberment, and eventual global distribution of which shapes human economic history in turn.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 10, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 10, 2007)” by David Maisel].

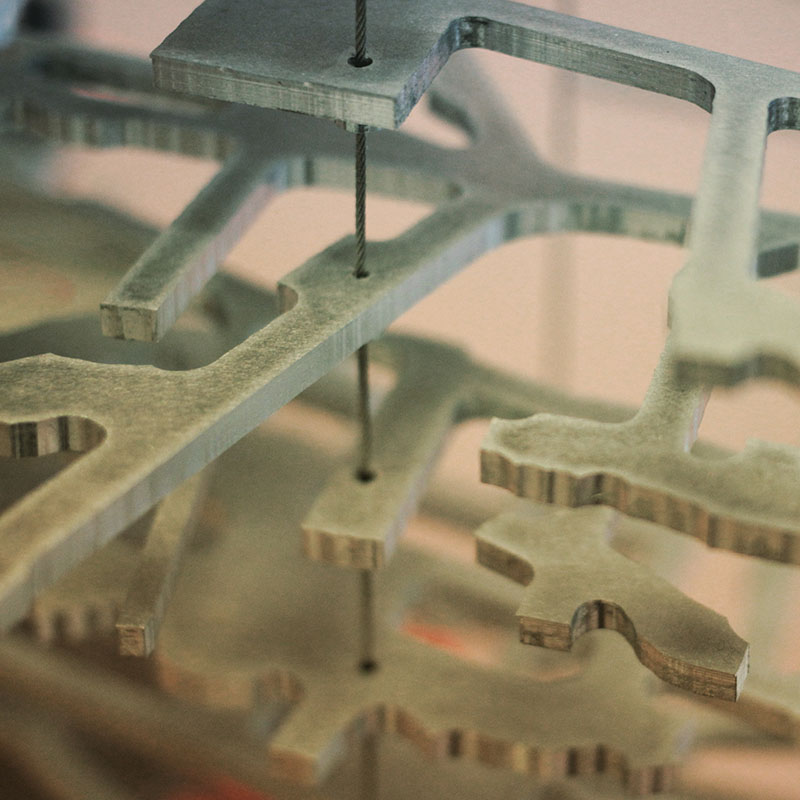

In any case, the form of a gold deposit itself must be mapped and clarified before excavation can begin. The shape of the ensuing pit is not the result of frantic, directionless digging, but of a carefully controlled design process. The word “design” is used deliberately here, even if the shape of the pit is orchestrated not by aesthetics but by the needs of financial rationality. Using proprietary graphics software—similar in function to visual effects programs used in film, gaming, and architecture—the ore body is predictively 3D-modeled.

Mining, at this point, becomes less an act of extraction than of physical verification: machines and their profit-minded operators pursue the outlines of a virtual form by gradually expanding the mine’s target zones, in effect checking to see if the geologists’ models were right.

As architect Liam Young suggested in a recent interview, conducted after he returned from leading a group of design students on a research trip to the gold mines of Western Australia,

mining engineers are basically designers. They develop all these fragmentary data into models, which become the design of the pit itself. … But then what happens is, based on gold prices, the pit model changes. In other words, if the gold price or the mineral price is higher, then the pit gets wider as it becomes cost-effective to mine areas of lower concentration. This happens nearly in real time—the speed of the machines digging the pit can change over the course of the day based on the price of gold, so the geometry of the pit is utterly parametric, modeling these distant financial calculations.

In essence, Young suggests, mining engineers produce and explore speculative models of gold distribution in the rocks below ground. Using surprisingly low-res data taken from seismic tests and weighing that data against equipment availability, labor costs, and, most importantly, the internationally recognized price of gold, the extraordinary ballet of machines can begin.

This then becomes predictive on a much larger scale, as well. By constantly refining their models of how exactly gold forms in the first place, and where and how it can be mined most effectively, geologists can understand where—and, to some extent, predict when—future ore bodies might accumulate. Interestingly, these future deposits will appear on a timescale that far exceeds human civilization—so, while human miners most likely won’t be around to exploit them, it’s nonetheless intriguing to know that serpent-like veins of precious metal are incubating in the darkness beneath us.

[Images: (top) “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 12, 2007)“; (bottom) “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 13, 2007),” by David Maisel].

[Images: (top) “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 12, 2007)“; (bottom) “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 13, 2007),” by David Maisel].

Here we return to Seabrook, who warns that “there is a good deal of poetry in these figures,” of ounces mined and subterranean veins discovered. “They are based on statistical models, a kind of three-dimensional game of connect the dots played by a computer.”

These are then treated explicitly and formally as works of art: Seabrook points out “a computer-generated three-dimensional picture of the ore body, dry-mounted and framed,” hanging on a geologist’s office wall. Call it the new Subterranean Romantic:

Mining people have a habit of stretching the metaphor when they talk about their ore bodies. They say how beautiful, how satisfying, how tantalizing their ore body is, they make hourglass shapes with their hands, knead with their fingers, smooth with their palms as they talk.

These gorgeous bodies, removed from the earth, leave scars: precisely designed but roughly implemented holes—exit wounds of temporally contingent value—clearly and deliriously visible from above.

[Images: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 12, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Images: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 12, 2007)” by David Maisel].

3.

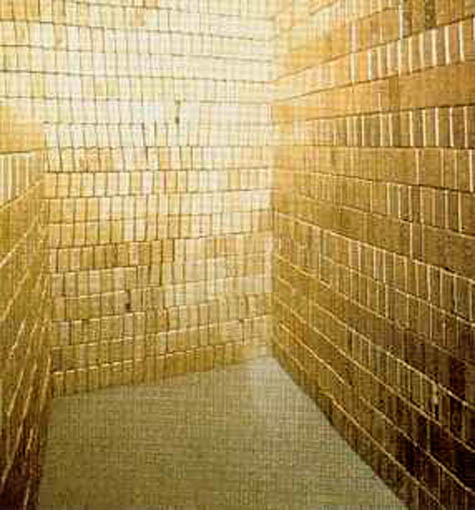

The very idea that gold has value is a funny thing. Aside from a few basic industrial uses, gold’s value is almost entirely ornamental—that is, it is agreed upon by financial traders and metals futures markets, even if no actual gold changes hands. Gold comes out of one, very carefully designed hole in the ground—whether in Nevada, South Africa, or Western Australia—only, most likely, to be interred again in another part of the world in a bank vault or federal reserve, where it is precisely gold’s removal from direct exchange that augments its value and its mystery.

Mystery is not used lightly. In his odd but insightful study of the various symbolic entanglements between gold, cocaine, violence, and colonial labor in South America, anthropologist Michael Taussig writes, with suitably mythic overtones: “How perfect is gold, the great shape-changer, the liquid metal, the formless form.”

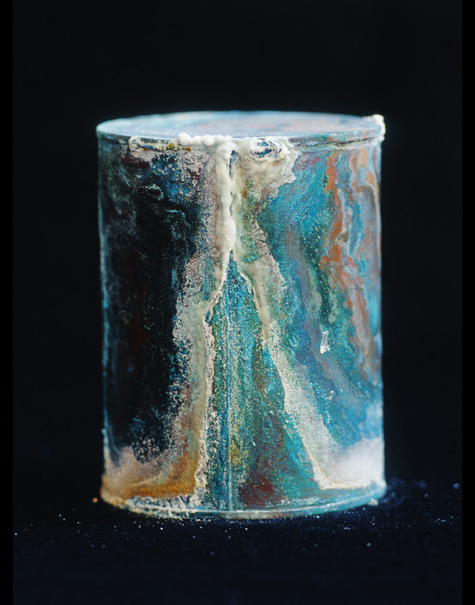

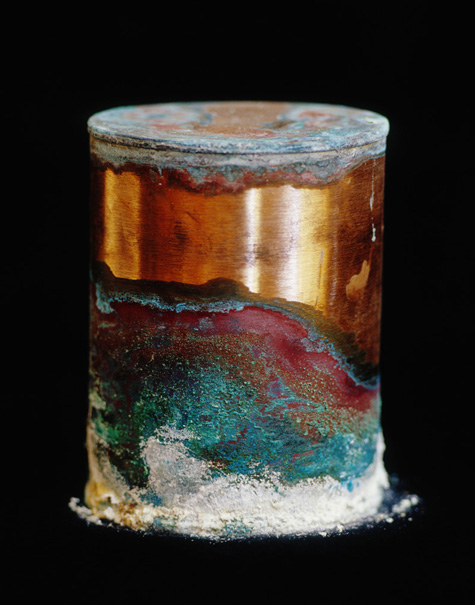

This “formless form,” however, undergoes a strange—we might say alchemical—transformation, from shining metal to the rarefied super-object known as money. In a long description based on a memoir by Captain Amasa Delano, Taussig recounts the nineteenth-century process of minting coins from gold bullion:

The gold ore was wetted and kneaded by blacks treading on it with their feet on a paved brick surface after which they put mercury on it so as to separate out the gold. Then the metal was heated, becoming red as blood. To get the liquid metal to run from its crucible, the spout was touched with a stick with a piece of cloth around it. When this stick made contact, there was a flash and the metal began to run in a stream not much thicker than a pipe stem. The bars of gold formed were subsequently squeezed flat by rollers until the thickness of a dollar or doubloon, by which time the bars had become sheets four feet long. A powerful press cut coins out from these thin sheets like a cookie cutter, and the pieces were turned to receive a milled edge. Then came the weighing.

For Taussig, this process reveals the machinations “both mysterious and everyday” by which a mineral becomes money—that is, how “gold and silver coins become enchanted, material things, aglow with a power emanating from deep within.” This base matter has been transformed, given exchange-value through formal regularity and sent off to participate in a global system of monetary transactions.

Gold coins are thus but one of the “minutiae in which the supernatural is secularized”: a haunted mineral is pulled from the earth and given an uncanny second life elsewhere.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 22, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 22, 2007)” by David Maisel].

The spectral mathematics that can turn reserves of gold into abstract instruments of monetary exchange—into financial products and debt instruments, derivatives and funds—operates through a barely comprehensible carnival of surrogates flashing back and forth through the global marketplace. Until the end of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971, when the US dollar was unilaterally decoupled from the international gold standard, gold served as a reliable, universally recognized equivalent for economic exchange.

Gold, in the words of Jean-Joseph Goux, himself citing Marx, had value precisely because it could so effectively disappear into the “circulation of substitutes.” This is a logic of exchange by which Object A can be traded for Object B, as long as we agree that Object B also refers, off-stage, to something else entirely: some standard or reserve for which it acts as a practical surrogate.

Before 1971, that off-stage presence—that silent original, sleeping in a state of eternal reservation—was gold.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 20, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 20, 2007)” by David Maisel].

To say, then, that there is an “economy” is thus to use shorthand for what Goux describes as “a regulated process of equivalents and substitutions,” whereby stand-ins, equivalents, and acceptable replacements all interact in occulted reference to an absentee original. The natural hard matter of gold, artificially extracted from the earth, thus becomes caught up in a supernatural system of objects: coins, bills, and derivatives—future duplicates and doubles.

In this context, the ongoing attempts to return the United States to the gold standard—by, for instance, perennial Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul—can be seen as an almost folkloristic attempt to put the genie of infinite derivative exchange back in the bottle.

Sites like Nevada’s Carlin Trend thus serve as base points for this process, emitting endless phantasms in an economic fiction of equivalents—derivative products that refer to one another in a superstition of indirect exchange referred to as the economy—to such an extent that we might say these mines can never be refilled. Or, more accurately, they can only be overfilled, stuffed beyond capacity with the carnival of substitutes their hollowing-out has, however inadvertently, unleashed.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 7, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 7, 2007)” by David Maisel].

4.

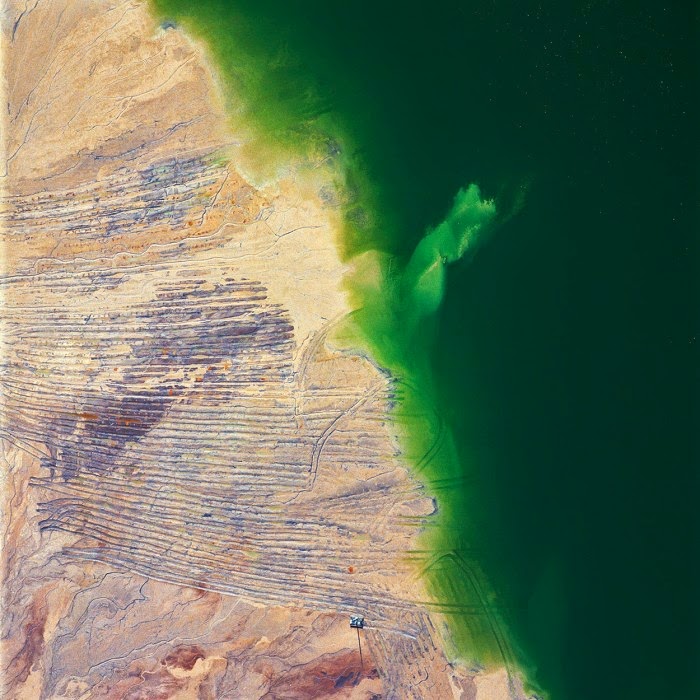

In 2007, David Maisel began work on a group of photographs called “American Mine,” part of a larger and older series known as “The Mining Project.” These images document, in extraordinary abstract swaths of color, the emergent geometries of mines along the Carlin Trend.

Scattered across Maisel’s images is a forensic survey of cuts and incisions—wounds that will outlive us, scars that won’t go away—older surgeries through which modernity has, in effect, been created. The mines of the Carlin Trend remain unhealed—in fact, year on year, they are growing—a raw scurvy of rocks exposed on a scale so monumental that geologists estimate mines, not cities, will be the final trace of humanity left visible in a hundred million years’ time.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 17, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 17, 2007)” by David Maisel].

Vast terraced bowls step down—and down and, impossibly, further down—tracking dead faults and mineralization fronts on a scale only made clear when we notice 16-ton trucks like specks of dust on canyon walls. Discolored oceans of chemical runoff wash across vehicle tracks with acid tides. Retaining walls and stabilized slopes loom over assembled superscapes of mine detritus, abandoned shells of industrial insects dwarfed by the world they’ve helped create.

In these scenes, geotextile mats have all but replaced the earth’s surface, offering instead a deathless, replicant topography. Artificial hills, each uncannily and exactly like its neighbor, roll from one side of the frame to the other, shifting in tandem with commodities prices, their malleable geography thus forever resistant to mapping. The mines grow and metastasize as voids: storm fronts of negative space exploding with their own slow thunder into the planet.

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 14, 2007)” by David Maisel].

[Image: “American Mine (Carlin, Nevada 14, 2007)” by David Maisel].

What is of particular interest in Maisel’s “American Mine” series is its revelation of the injuries at the start of the commodity chain: planetary wounds, seemingly beyond the breadth of nature, out of which commodities have been extracted for later exchange.

The production of economically recognizable objects can thus be seen as a kind of terrestrial focusing: out of the chaos of the mine site, with great lakes clouded by geochemical effluent and abstract landforms like ritual mounds from human prehistory, pristine products eventually emerge, assembled from these heavy elements torn so roughly from the ground. Out of the carcinogenic discord of rock dust, circuit boards appear.

In a sense, it is surprising that the computers, phones, batteries, television sets, and other mundane electronics that fill the markets of the world are so free of this fallout, so astringently cleansed of the geological evidence of their own creation. Or perhaps we might say that it is precisely this stripping-away of a product’s elemental birth that gives it its later value and utility. Such products are ironically de-terrestrialized: washed of the very planet from which they came.

• • • I owe a huge thank you to David Maisel and editor Alan Rapp for inviting me to participate in the

Black Maps book, which is an absolutely gorgeous compendium of Maisel’s work, as well as to Sina Najafi for his editorial feedback before this essay ran in

Cabinet Magazine. You can see some photos of

Black Maps over at the publisher’s website.

For those of you in Los Angeles, meanwhile, Maisel has a new show opening this spring—on March 26th, 2015—at the Mark Moore Gallery. Check back at this link in the weeks to come for more information.

Finally, if you would like to read some previous posts here on BLDGBLOG about Maisel’s work, don’t miss “The Fall” or “Library of Dust,” among many other short posts; and be sure to read the interview with David Maisel published in The BLDGBLOG Book.

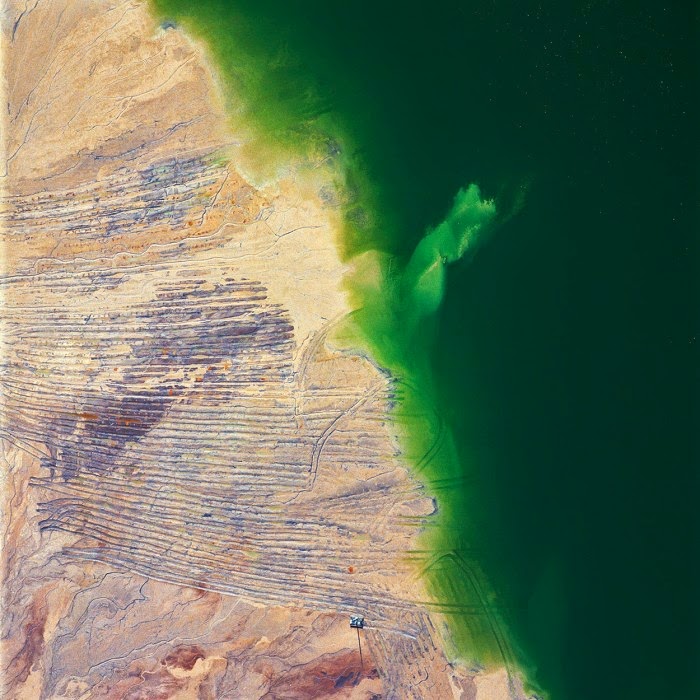

[Image: Nickel-rich sap; photo by Antony van der Ent, courtesy New York Times.]

[Image: Nickel-rich sap; photo by Antony van der Ent, courtesy New York Times.]

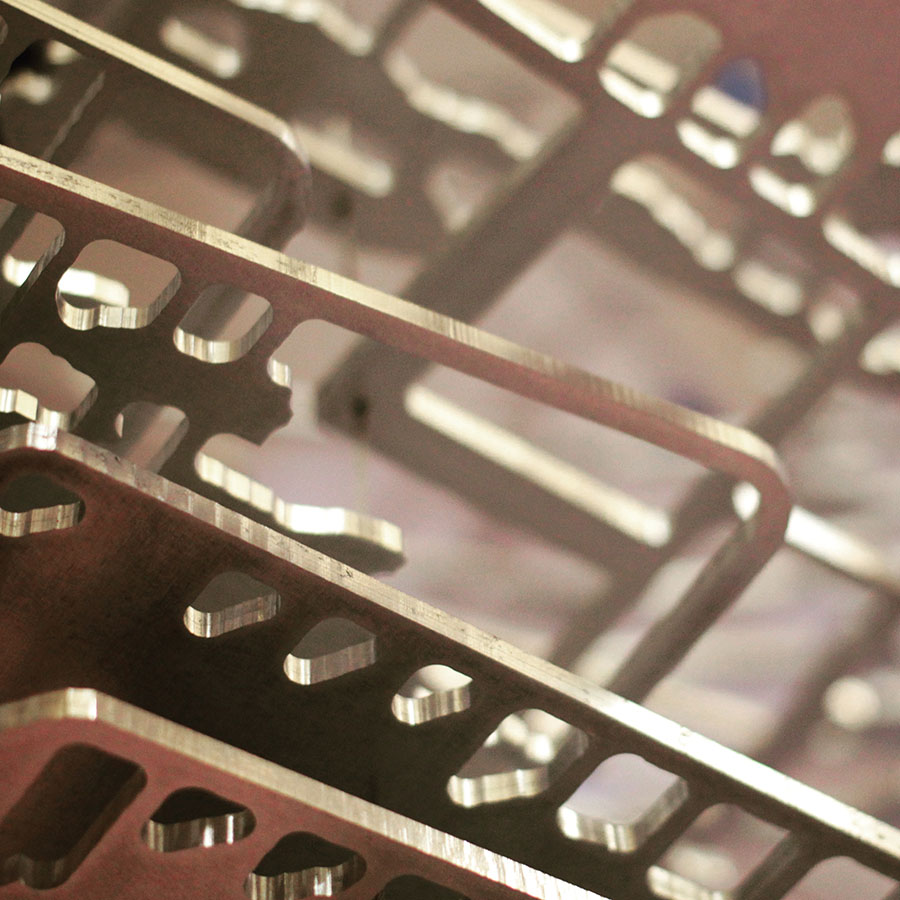

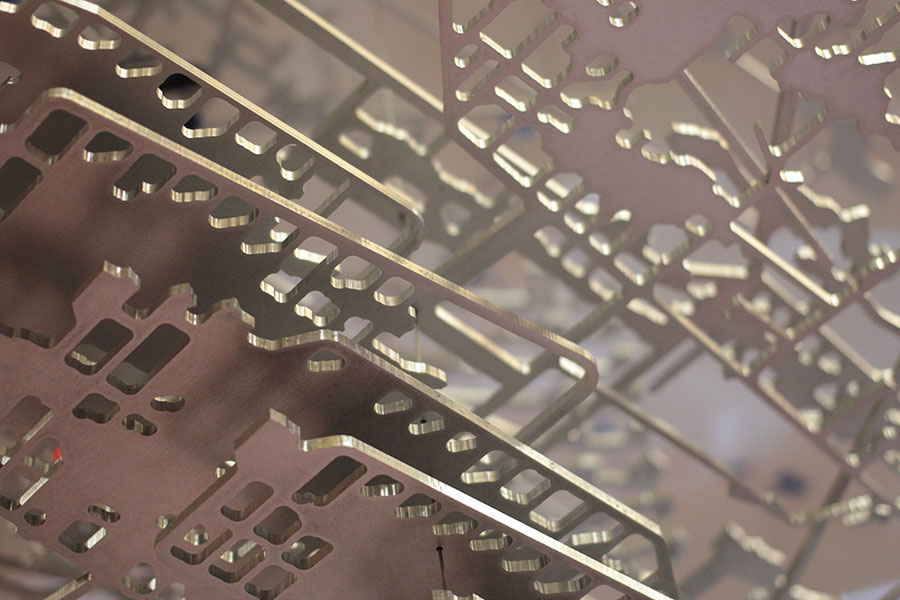

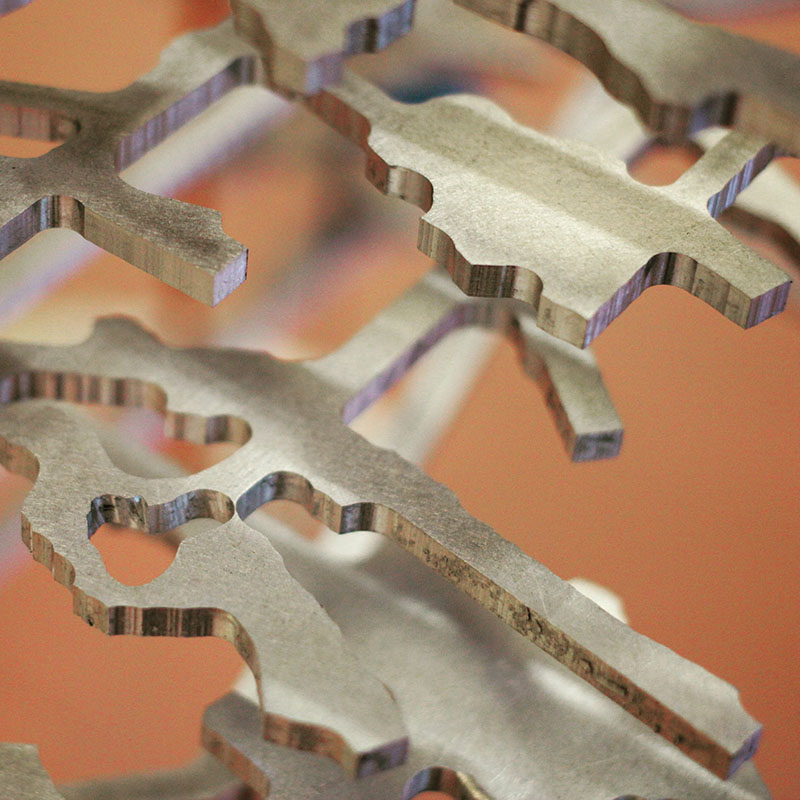

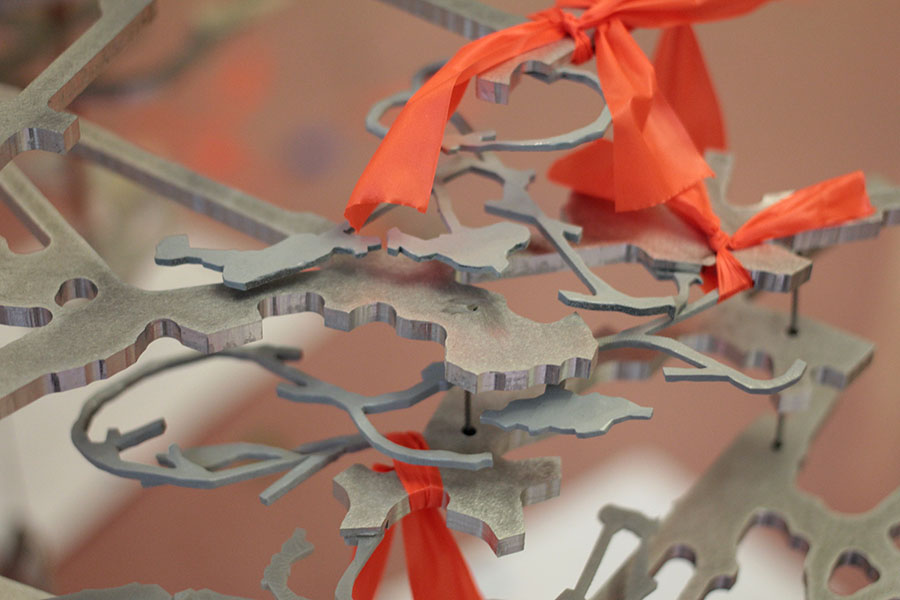

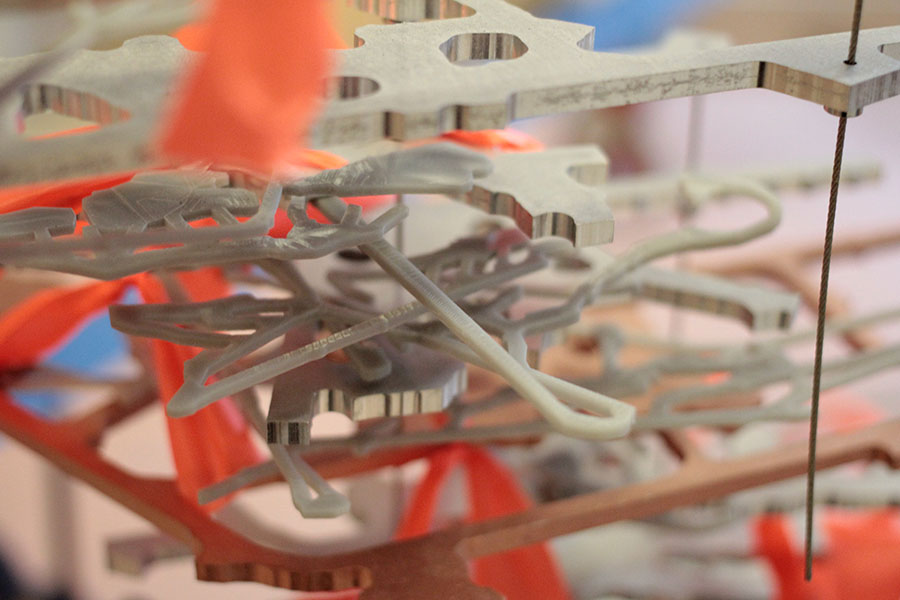

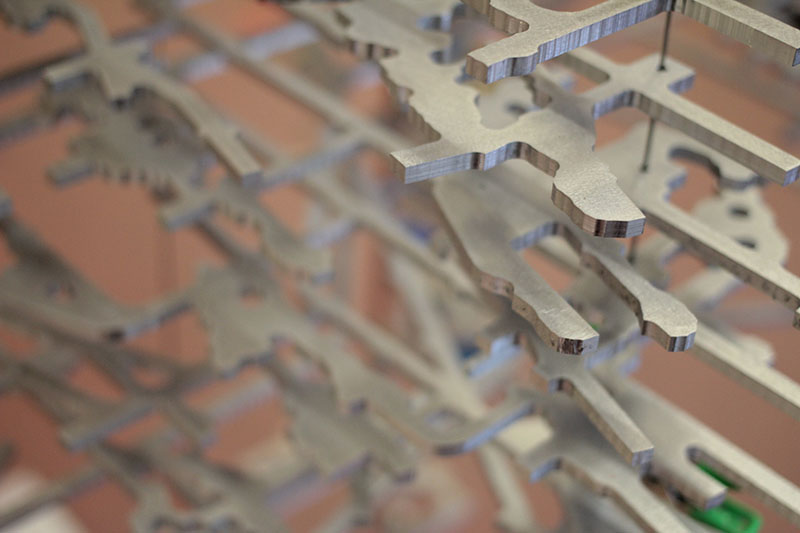

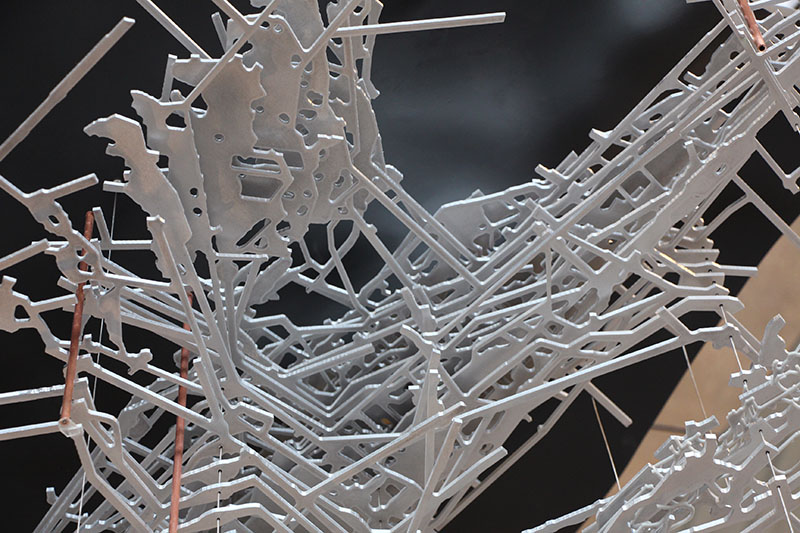

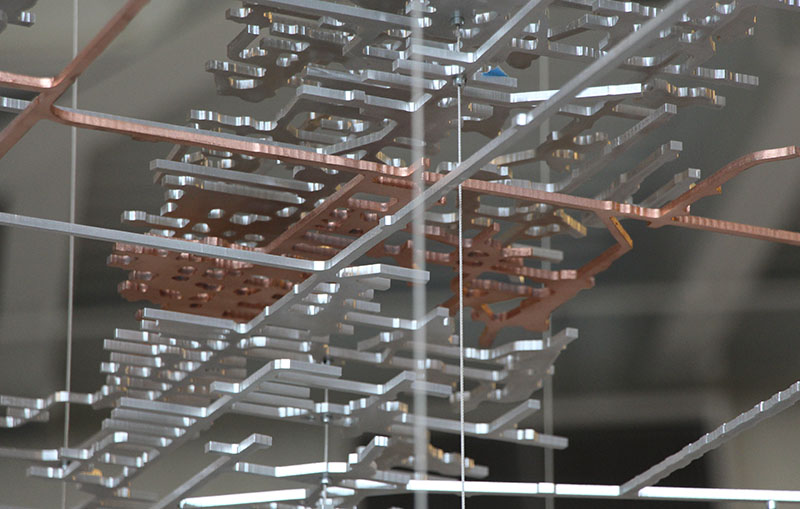

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via  [Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Assembly of the model by

[Image: Assembly of the model by

[Images: Model by

[Images: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Assembly of the model by

[Image: Assembly of the model by  [Image: Assembling the model by

[Image: Assembling the model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by

[Images: The model seen in situ, by

[Images: The model seen in situ, by  [Image: The model by

[Image: The model by

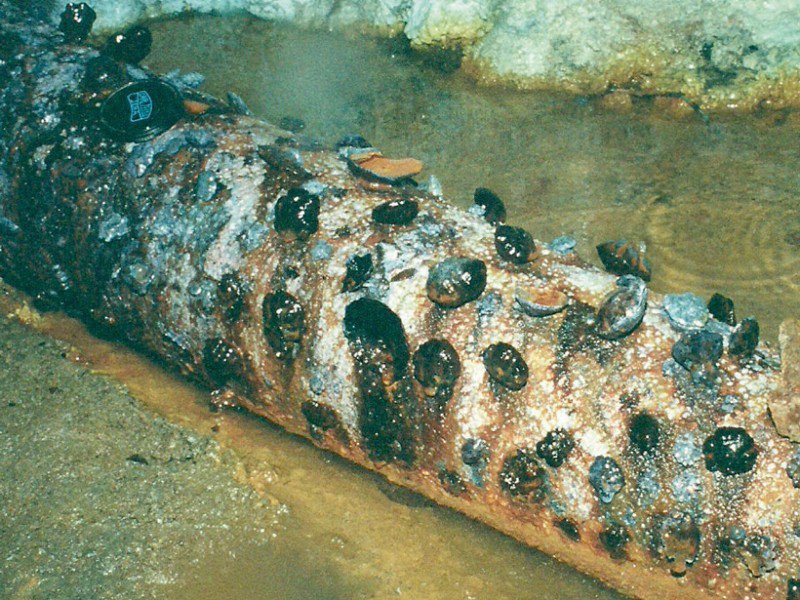

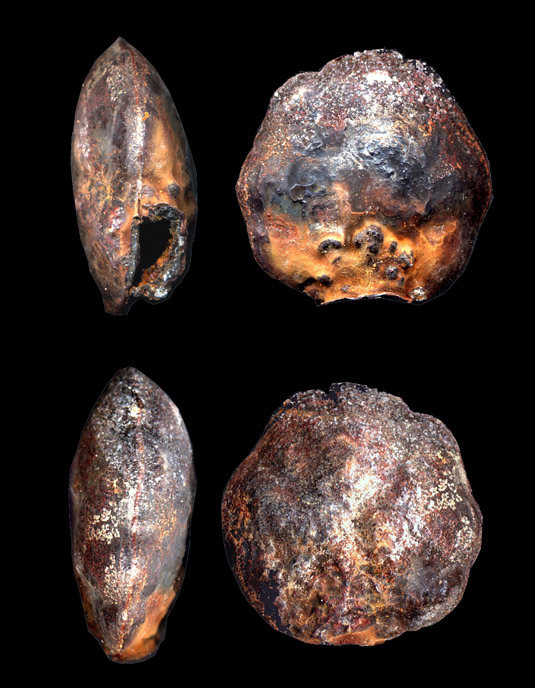

[Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by

[Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by  [Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by

[Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by  [Image: An “

[Image: An “

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: (top) “

[Images: (top) “ [Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914].

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914]. [Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via  [Image: Stackin’ it at the

[Image: Stackin’ it at the  [Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at

[Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Abandoned rooms of the hospital. From

[Image: Abandoned rooms of the hospital. From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From