Thomas Mullen is the author of The Last Town on Earth, a novel set in a voluntarily quarantined village in the remote forests of the Pacific Northwest during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918.

From the book’s description:

From the book’s description:

The year is 1918. America is fighting a war on foreign soil that has divided the nation. Meanwhile, rumors of the spread of the deadliest epidemic ever are causing panic on the home front. The uninfected town of Commonwealth, Washington, votes to quarantine itself, and two young friends are asked to guard the town entrance and keep strangers out.

One day, a starving, cold—and seemingly ill—soldier comes out of the woods begging for sanctuary, and the two guards are confronted with an agonizing moral dilemma.

The Last Town on Earth was named the Best Debut Novel of 2006 by U.S.A. Today – who describe it as “an absorbing depiction of a utopian town that attempts to keep the 1918 flu epidemic at bay” – and it won the James Fenimore Cooper Prize for Excellence in Historical Fiction.

As part of our ongoing series of quarantine-themed interviews, Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and I spoke to Mullen about his novel, about the historical research that informed it, and about the moral implications of mass quarantine.

• • •Edible Geography: What sort of research went into writing the novel?

Thomas Mullen: The impetus for the book was an article that I read many years ago about an AIDS virologist who had studied the 1918 flu earlier in his career. It also mentioned, parenthetically, that there had been healthy towns in the Rocky Mountain states and in the Pacific Northwest that were so terrified by stories about how contagious the flu was, and how fatal it was, that they decided their best recourse for staying healthy was to block off all the roads leading into town and to post armed guards to prevent anyone from coming in. That just blew me away—it was amazing to read that this had happened—and I thought it would be a very dramatic first scene.

I was hooked by the moral dilemma of quarantine: what happens if, one day, you and your buddy are standing guard over your town and you’re presented with a lost traveler? He’s freezing, and he’s starving, and he’s begging for your aid. He needs food and shelter, or he might die. What do you do? Do you bring this person in? Do you try to be charitable, even if you know he might be carrying this awful virus that you don’t really understand? Again, it was 1918 and their understanding of the virus was certainly worse than ours is today. Or do you tell you the person: “Hey, I’m sorry, but I need to think of my friends and family and my town. I don’t know what you might be carrying, and you’re just going to have to die in the woods.”

That’s what made me want to write the book. I sat down and I read a few books about the 1918 flu—although I couldn’t find many. It had become this overshadowed chapter in history. That’s starting to change now; with the new concern about avian flu and H1N1, there’s been much more discussion of the 1918 epidemic. But, back when I started my research, it was hard to find much information.

I tried to find out about these towns that had done this—these sort of reverse-quarantines. That’s just a phrase that I invented; I don’t know if there’s a real phrase for it. Normally, quarantine is when something or someone is ill and they’re quarantined off so that they don’t spread their germs to the rest of us. But in this situation, the town that closes itself off is healthy. I called that reverse-quarantine.

I couldn’t really find anything out about these towns. In fact, when I was about three-quarters done with the rough draft, a historian named John Barry wrote what is now the definitive history of the 1918 flu, called The Great Influenza. I got that book and I read it—and it’s about 600 pages long, but he only gives about half a page to this phenomenon of Western towns that had closed themselves off. He says that it worked for some and it didn’t work for others—and that’s it.

[Image: Historical quarantine marker].

[Image: Historical quarantine marker].

Edible Geography: Was reverse-quarantine a common phenomenon and just under-reported, or was it actually fairly rare?

Mullen: It doesn’t sound like it was very common. After all, if it only got about half-a-page in a 600-page book… It’s just something I could not find reference to very often.

They were probably small towns that were already fairly isolated, and therefore might not have left such a good paper trail for historians to write about. It must have been fairly unusual in the first place, because the flu spread very, very quickly, so usually it was too late. By the time you were thinking that maybe you should close the borders, people were already getting sick in your town—so you missed the opportunity.

Meanwhile, because our nation was at war, there was censorship of the press. Newspapers didn’t want to report bad news. People didn’t often know what was happening until it was too late. Instead, newspapers would have a little pick-me-up story about how some soldiers in a nearby army base had a bad case of the flu… but they’re feeling much better now. Meanwhile, people are looking out their windows and seeing hearses! If there had been a free press, and if the government had not been distracted by a war and had shared information about it sooner, it’s possible that more towns would have tried quarantine. But for most people, by the time they realized what was happening, it was too late.

I think the reason why the towns that did this were in the Rocky Mountains and in the Pacific Northwest was that they were inland and fairly isolated. The flu had started, most epidemiologists believe at this point, in army bases, and then it had traveled along the rail lines, from army base to army base; and from port to port—meaning cities like Philadelphia and Boston and New Orleans and San Francisco—and it gradually trickled inland. Some of the mountain states were the last to get infected – and they were the ones where, finally, the story was out. They were the ones who knew what was happening, so some of them were able to make this decision.

Ultimately, though, because I’m a novelist—I write fiction, and I can make things up—I decided, okay, maybe it’s better that I don’t know exactly what happened in these towns. Maybe that frees me up a bit. I did as much research as I could into how the epidemic worked, how the disease itself worked, and what the political environment was like at that time in America—what these characters were doing and what they were thinking about. But, as for what had actually befallen towns that tried this, I was sort of unconstrained by historical fact—which, I think, was a good thing.

BLDGBLOG: That raises the question of your own interest, as a novelist, in the idea of quarantine. What are the narrative possibilities of quarantine that drew you to it, as a plot device?

Mullen: As a novelist, you need there to be some stress, because that creates the tension between the characters. It leads them to act – sometimes in inappropriate or regrettable ways.

One of the things that I was really interested in doing with this book was studying the way in which people act differently from the way they would like to think they act, under stress. We have this idea of ourselves as good people, and we have moral guidelines that we like to believe we follow, but when we feel threatened and we feel that our family is in danger, we tend to bend some of those rules. Whether that means shooting a stranger who’s trying to come into your town, or whether that means shutting out your neighbor because you think they might have a cold – things like that.

I was interested in looking at the stresses that these people would be under. First of all, externally, they feel they’re safe in their little town—but the world around them is dangerous, with everyone being ill. Also, in those political times, there were things happening that the utopians in my little mill town didn’t agree with; they’re very anti-war and anti-capitalist. They feel at odds with the world, and they’re closing themselves off from a world that they disagree with in many ways. But when the disease does get into the town, they’re at odds with each other: some are sick, some are healthy. New stresses are introduced; they start running out of food and out of things that they need to maintain their quarantine.

[Images: The town of Jerome, Arizona, during the 1918 flu outbreak; note the face masks. Courtesy of the Jerome Historical Society, via the Sharlot Hall Museum].

[Images: The town of Jerome, Arizona, during the 1918 flu outbreak; note the face masks. Courtesy of the Jerome Historical Society, via the Sharlot Hall Museum].

Edible Geography: Much of your book is focused on the moral dilemmas associated with implementing and enforcing quarantine. What drew you to that?

Mullen: That was something that I didn’t seek out to do, but, as I was writing the story, it came naturally. You have these utopian idealists and political activists who are anti-war and pro-union, and they’re early suffragists. Some of them support the quarantine because they want to stay healthy; they want to protect their families. But some of them, because their political beliefs are so strong, realize that, hey, I have these beliefs because I want to make the world a better place. I don’t want to just make my town a better place. And what are the moral implications of turning our back on a world that is suffering? Isn’t it our obligation to do something that would improve the world? Some people feel that the best way to make a better world is to focus on yourself, and on your own community, and to hope the world will emulate it. Others—more activist—think they need to get out there. I’m interested in that conflict.

And, of course, that line is itself blurred—because they all support the quarantine initially. Even those who opposed it refused to leave. So, theoretically, everyone in the town in chapter one is cool with the idea. But, as time goes on, some people are thinking, god, I’m bored, I want to get out of here; or we learn that they’ve been secretly sneaking out to visit women or buy booze. So even the people who had initially agreed with it came to feel that it had been imposed on them. They change their minds—but it’s too late.

BLDGBLOG: In a way, you illustrate the fundamental impossibility of a total quarantine: there’s always something getting in or getting out, usually due to human weakness or error.

Mullen: I can’t remember if that’s something that I always intended—that I was going to have these people sneaking out—or if that was something that came up halfway. But it just seemed right to me. The whole dilemma of utopian politics, in general, is: can we really make the world a perfect place? I think there is enough human frailty and vice out there that something will always sabotage it.

Medically speaking, I know that quarantine can work, but, with something on the scale of a whole town, I can’t help but wonder: would it really work? It didn’t in the book because it was this slapdash affair; you’ve got randomly chosen people standing guard. But I think if it were to happen now, with a city or a state, you’d have National Guard or police or army officers standing guard, and I don’t think they would bend quite the way my characters would bend. But then you have the other problem—where it becomes a police state—and people aren’t allowed to come and go. It might work to keep the disease out, and people might thank them for that, but they might also feel like their rights were being violated. It gets really complicated.

[Image: A sick ward for those infected with the 1918 Spanish flu].

[Image: A sick ward for those infected with the 1918 Spanish flu].

Edible Geography: Why do you think there has been such a historical silence about the epidemic?

Mullen: My partly cynical answer is that we Americans just don’t know our history very well!

I did a panel once with two other writers who both had novels set during World War I, and they were both British. They talked about how World War I is a big deal in the UK: how everybody knows about it; you see plaques everywhere listing the dead; and there were some towns where, in one night, the entire population of young men died, because they had this idea that men in the same town could enlist together and fight in the same regiment. This meant that you got to enlist with your friends, and you got to fight with your friends, which was great for morale—but what it also meant it that you died with your friends. There were literally towns where all the young men died on the same day, in one of those major battles.

It was a profound experience for so much of Europe, where they fought the war for years on their home soil. For America, on the other hand, we were only involved militarily for about year. We declared war earlier on, but it took a while just to get an army together, because we didn’t even have a standing army. And, of course, it wasn’t fought on our own soil. So the flu took place during the war, and the war itself is just not very well-taught or well-understood here.

But, also, in terms of why do people know about the war and not the flu, can it be that history textbooks can only handle one big subject at once? They’re writing about the war and they just didn’t think they needed to mention the flu? A disease doesn’t have the geopolitical themes that you get to play with when you’re teaching about a war or a politician or a movement; it was this horrible thing that just happened.

Also, I wonder how much of it was simply the fact that the people who lived through it just wanted to build a wall around those memories; they didn’t have our mindset, where we need to come to terms with our past and expose our scars in order to find closure. I think the survivors, to some degree, probably felt that it’s over – and it was horrible – but the last thing to do was to talk about it.

At this point, it’s enough generations away that there’s very little memory of it left – people only remember being told about it. Another horrible thing about the flu was that it killed so many adults and it left so many orphans. A lot of the survivors were very young children, who really don’t remember it for themselves.

But it was interesting to me that so many of the great literary lions in the early 20th century were people who lived through this when they were teenagers or young adults—Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, Steinbeck—and none of them wrote about it. It now seems like of course you would write about this.

• • •This autumn in New York City,

Edible Geography and BLDGBLOG have teamed up to lead an 8-week

design studio focusing on the spatial implications of quarantine; you can read more about it

here. For our studio participants, we have been assembling a coursepack full of original content and interviews—but we decided that we should make this material available to everyone so that even those people who are not in New York City, and not enrolled in the quarantine studio, can follow along, offer commentary, and even be inspired to pursue projects of their own.

For other interviews in our quarantine series, check out Isolation or Quarantine: An Interview with Dr. Georges Benjamin, Extraordinary Engineering Controls: An Interview with Jonathan Richmond, On the Other Side of Arrival: An Interview with David Barnes, and Biology at the Border: An Interview with Alison Bashford.

Many more interviews are forthcoming.

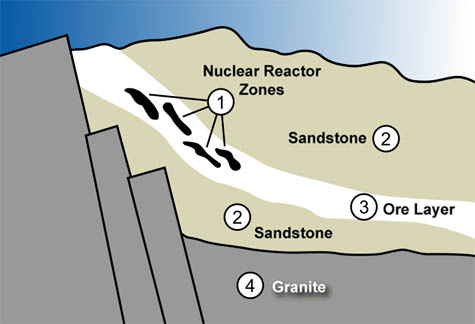

[Image: The natural clocks and ticking stratigraphy of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the Curtin University of Technology].

[Image: The natural clocks and ticking stratigraphy of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the Curtin University of Technology]. [Image: A diagram of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy].

[Image: A diagram of the Oklo uranium deposit, courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy]. From the book’s description:

From the book’s description: [Image: Historical quarantine marker].

[Image: Historical quarantine marker].

[Images: The town of Jerome, Arizona, during the 1918 flu outbreak; note the face masks. Courtesy of the Jerome Historical Society, via the

[Images: The town of Jerome, Arizona, during the 1918 flu outbreak; note the face masks. Courtesy of the Jerome Historical Society, via the  [Image: A sick ward for those infected with the

[Image: A sick ward for those infected with the  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

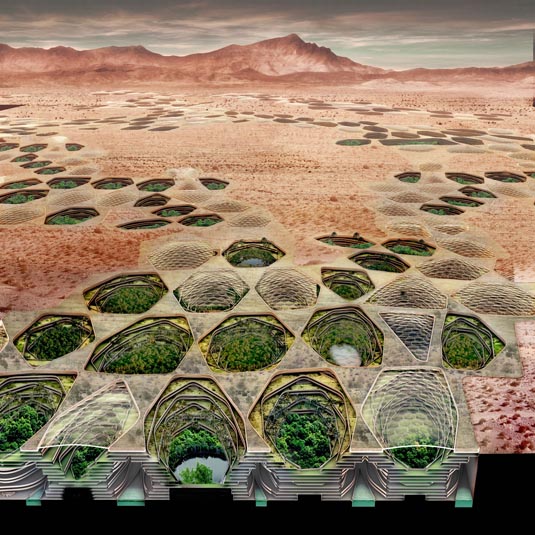

[Image: From  [Image: Matsys’s

[Image: Matsys’s  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: From

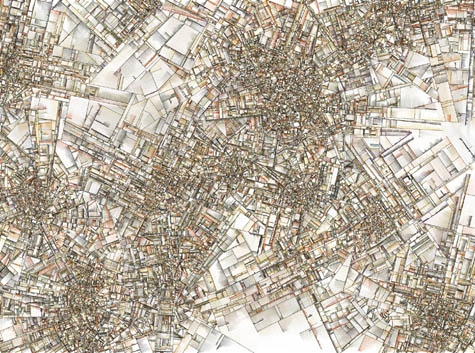

[Image: From  [Image: From Jared Tarbell’s

[Image: From Jared Tarbell’s

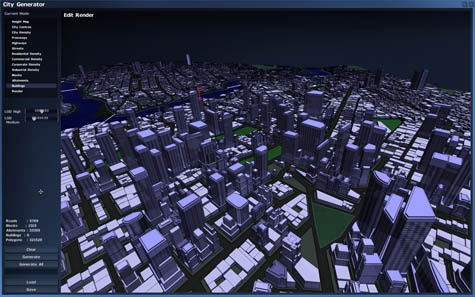

[Images: From Chris Delay’s

[Images: From Chris Delay’s  [Image: From

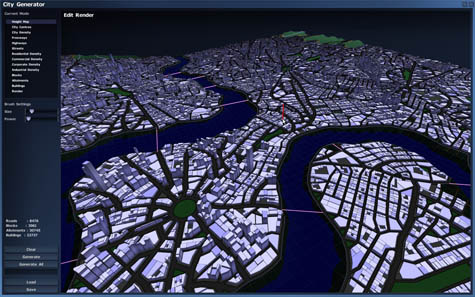

[Image: From  [Image: From Chris Delay’s

[Image: From Chris Delay’s  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: From Marco Corbetta’s Structure].

[Image: From Marco Corbetta’s Structure]. [Image: A Greenland ice-core at the

[Image: A Greenland ice-core at the  [Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via

[Image: A satellite view of the city-block core sample, via  [Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly

[Image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis, showing the Balbi Theater. For more on the Forma Urbis, visit the seemingly great but non-Mac-friendly  [Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta’s ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)].

[Image: Museum display panel diagramming five distinct road levels wandering across the Crypta’s ruins (apologies for the quick snapshot)]. [Image: An interior view of the

[Image: An interior view of the  [Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film

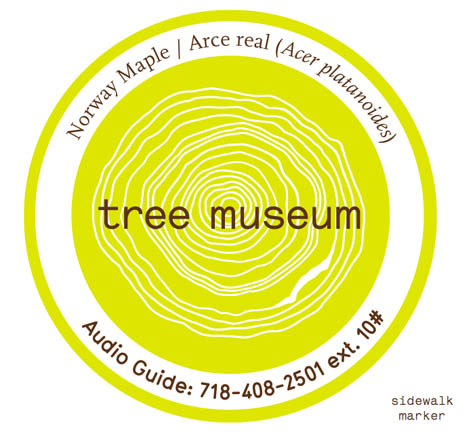

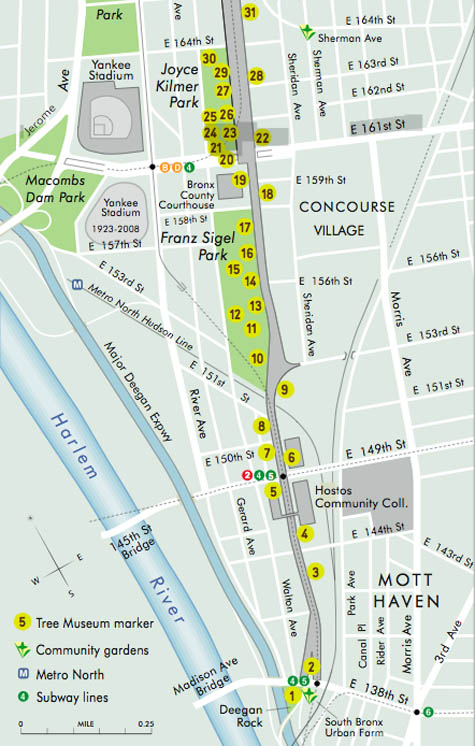

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film  [Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].

[Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number]. [Image: A section of the

[Image: A section of the  [Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].

[Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University]. [Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].

[Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten]. [Image: The Bronx

[Image: The Bronx  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Ebenezer Howard’s original scheme for the

[Image: Ebenezer Howard’s original scheme for the  [Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), ©

[Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), © [Image: From Mikey Tomkins’s series of

[Image: From Mikey Tomkins’s series of