[Images: I’ve been enjoying a new Instagram feed called The Jefferson Grid, which describes itself as “everything that fits in a square mile.” These images are just screen grabs from the feed, which is well worth scrolling back through in its entirety (and which will hopefully stick around for many more square-mile images to come)].

[Images: I’ve been enjoying a new Instagram feed called The Jefferson Grid, which describes itself as “everything that fits in a square mile.” These images are just screen grabs from the feed, which is well worth scrolling back through in its entirety (and which will hopefully stick around for many more square-mile images to come)].

“It’s almost like he wanted to collect every map ever made”

Alec Earnest recently made an interesting documentary about a house in Los Angeles whose owner died, leaving behind a personal map collection so massive that, upon being acquired by the city’s public library, “it doubled the LAPL’s collection in a single day.”

When LAPL map librarian Glen Creason, interviewed for the film, first entered the house, his jaw dropped; “everywhere I looked in the house, there’s maps,” he explains in the film, including an entire floor that was “absolutely wall to wall with street guides.”

[Image: From Living History: The John Feathers Map Collection by Alec Earnest].

[Image: From Living History: The John Feathers Map Collection by Alec Earnest].

As the Los Angeles Times described Feathers’s house upon its discovery back in 2012, it held “tens of thousands of maps. Fold-out street maps were stuffed in file cabinets, crammed into cardboard boxes, lined up on closet shelves and jammed into old dairy crates. Wall-size roll-up maps once familiar to schoolchildren were stacked in corners. Old globes were lined in rows atop bookshelves also filled with maps and atlases.”

It went on and on and on: “A giant plastic topographical map of the United States covered a bathroom wall and bookcases displaying Thomas Bros. map books and other street guides lined a small den.”

Urban atlases, motoring charts, pre-Thomas Guide local street maps—Feathers collected seemingly any cartographic ephemera he could get his hands on.

[Image: From Living History: The John Feathers Map Collection by Alec Earnest].

[Image: From Living History: The John Feathers Map Collection by Alec Earnest].

Earnest’s short film has more information about Feathers himself, and can seen in full either above or over on YouTube.

Although the story of the collection would lend itself well to longer journalistic exploration—and map librarian Glen Creason has actually written up some thoughts for Los Angeles Magazine—it feels like an amazing jumping off point for a piece of fiction, either cinematic or literary.

Perhaps some sort of Chinatown or True Detective-like property speculation noir, where parcels of land and off-books deals are being tracked by a lone collector through generations of local maps, marking boundaries, street names, omissions; or perhaps something more like “X Marks the Spot,” where an old Spanish-affiliated property from the pre-Los Angeles era is rumored to have once had vast brick vaults stocked high with gold, buried beneath the main ranch house, a property long since absorbed into the supergrid of Greater Los Angeles… but the vaults are still down there—along with the gold—if only you can dig up the right map to go find it.

[Image: From Living History: The John Feathers Map Collection by Alec Earnest].

[Image: From Living History: The John Feathers Map Collection by Alec Earnest].

In fact, there could be a whole genre based purely on the unexpected narrative side-effects of people attempting—and failing—to map Los Angeles.

Abandoned Basements as Stormwater Basins

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via Landscape Architecture Magazine].

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via Landscape Architecture Magazine].

Not all the news coming out of Milwaukee involves misguided highway megaprojects or tax-funded crony capitalism—though there is that.

For example, Wisconsin governor Scott Walker—confusing an earlier generation’s urban mistakes with how a city is meant to function—has been plowing billions of dollars’ worth of taxpayer money into “freeway megaprojects” for which “the pricetag got so big that leaders from his own party rejected his plan as fiscally irresponsible, leaving the state budget in limbo,” Politico reports:

As the state has shifted resources into freeway megaprojects, 71 percent of [Wisconsin’s] roads are in mediocre or poor condition, according to federal data. Fourteen percent of its bridges are structurally deficient or functionally obsolete, which is actually better than the national average. Walker and his fellow Republicans have killed plans for light rail, commuter rail, high-speed rail, and dedicated bus lanes on major highways, so there is almost no public transportation connecting Milwaukee to its suburbs, intensifying divisions in one of the nation’s most racially, economically and politically segregated metropolitan areas. Yet Walker, who is running for president as a staunch fiscal conservative, has pushed a $250 million-per-mile plan to widen Interstate 94 between the Marquette and the Zoo despite fierce local opposition.

If that sounds both avoidable and unfortunate, consider the fact that “Walker also killed a ‘Complete Streets’ program that pushed road builders to accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians.”

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via Politico].

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via Politico].

At the same time, Walker has also “championed a high-profile proposal to spend a quarter of a billion dollars of taxpayer money to help finance a new Milwaukee Bucks arena—all while pushing to slash roughly the same amount from state funding for higher education,” the International Business Times reports.

But, hey, why does Wisconsin need universities when everyone can just go to an NBA game? Not that benefitting the public is even Walker’s goal: “One of those who stands to benefit from the controversial initiative is a longtime Walker donor and Republican financier who has just been appointed by the governor to head his presidential fundraising operation.”

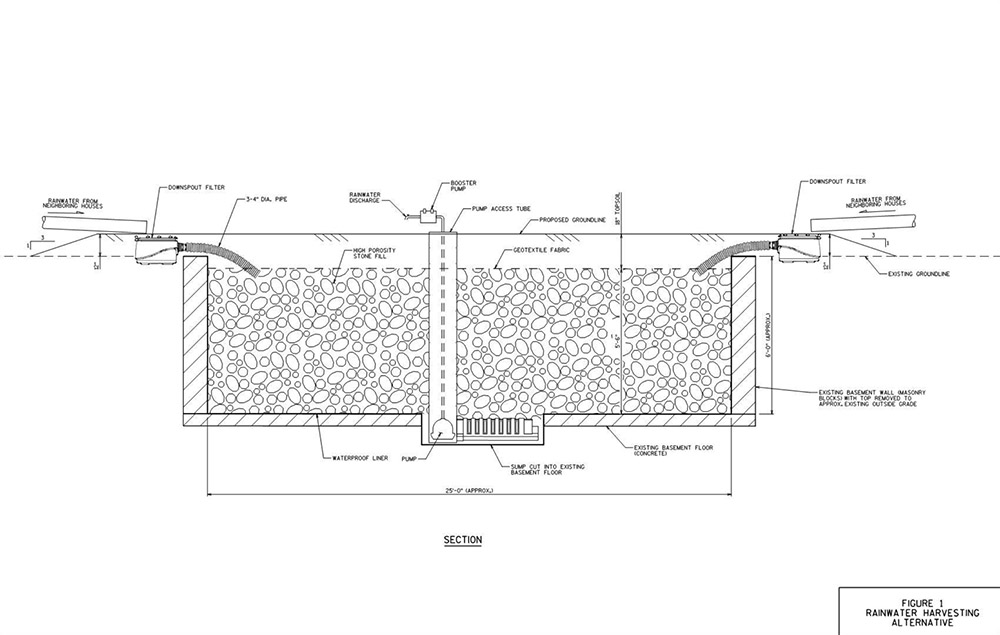

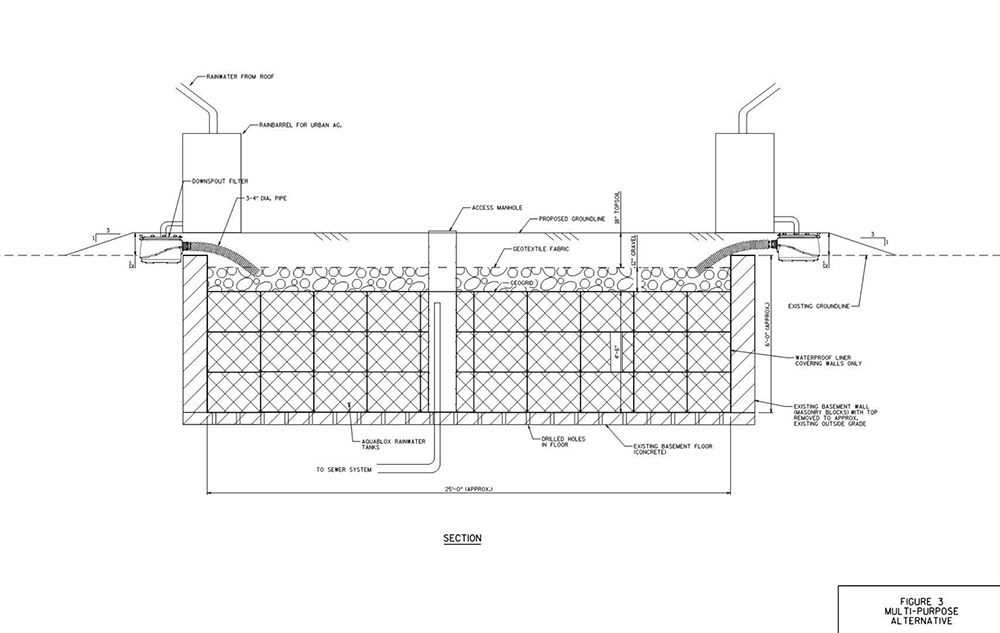

In any case, an interesting landscape test-project is currently underway in Milwaukee, called the “BaseTern” program.

As the city explains it, a “BaseTern” is “an underground stormwater management or rainwater harvesting structure created from the former basement of an abandoned home that has been slated for demolition.” Why is the city doing this?

By using abandoned basements, the City saves the cost of demolition on these structures (filing the basement and grading the surface) and on excavation for the new structure. In addition, BaseTerns provide significant stormwater storage capacity on a single site, the equivalent of up to 600 rain barrels.

The result, the city is keen to add, is “not an open pit. Rather a BaseTern is a covered structure, which is covered with topsoil and grass, and will appear the same as conventional vacant lot.”

In their July 2015 issue, Landscape Architecture Magazine explained that this is, in fact, “the world’s first such system.” Conceived—and actually trademarked—by a city official named Erick Shambarger, the idea was inspired by a GIS-fueled discovery that the worst flooding in the city always “occurred in neighborhoods with high rates of foreclosures. The city controls roughly 900 foreclosed properties, many of which it plans to demolish. Shambarger figured the city could preserve the basement structure and put it to use.”

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “Vacant Basements for Stormwater Management Feasibility Study“].

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “Vacant Basements for Stormwater Management Feasibility Study“].

While there is something metaphorically unsettling in the idea that parts of a blighted, financially underwater neighborhood might soon literally be underwater—transformed into a kind of urban sponge for the rest of Milwaukee—the notion that the city can discover in its own economic misfortune a possible new engineering approach for dealing with seasonal flooding and super-storms is an inspiring thing to see.

The BaseTern program also potentially suggests a stopgap measure for coastal cities set to face rising sea levels well within the lifetimes of the coming generation.

In the all but inevitable managed retreat from the coast that seems set to kick off both en masse and in earnest by midcentury—something that is already happening in New York City, post-Sandy—perhaps the subterranean ruins of old neighborhoods left behind can be temporarily repurposed as minor additions to a broader coastal program intent on reducing flooding for residents further inland.

Before, of course, those underground voids—former guest bedrooms, dens, man caves, she sheds, and basements—are inundated for good.

Read more about BaseTerns over at Landscape Architecture Magazine.

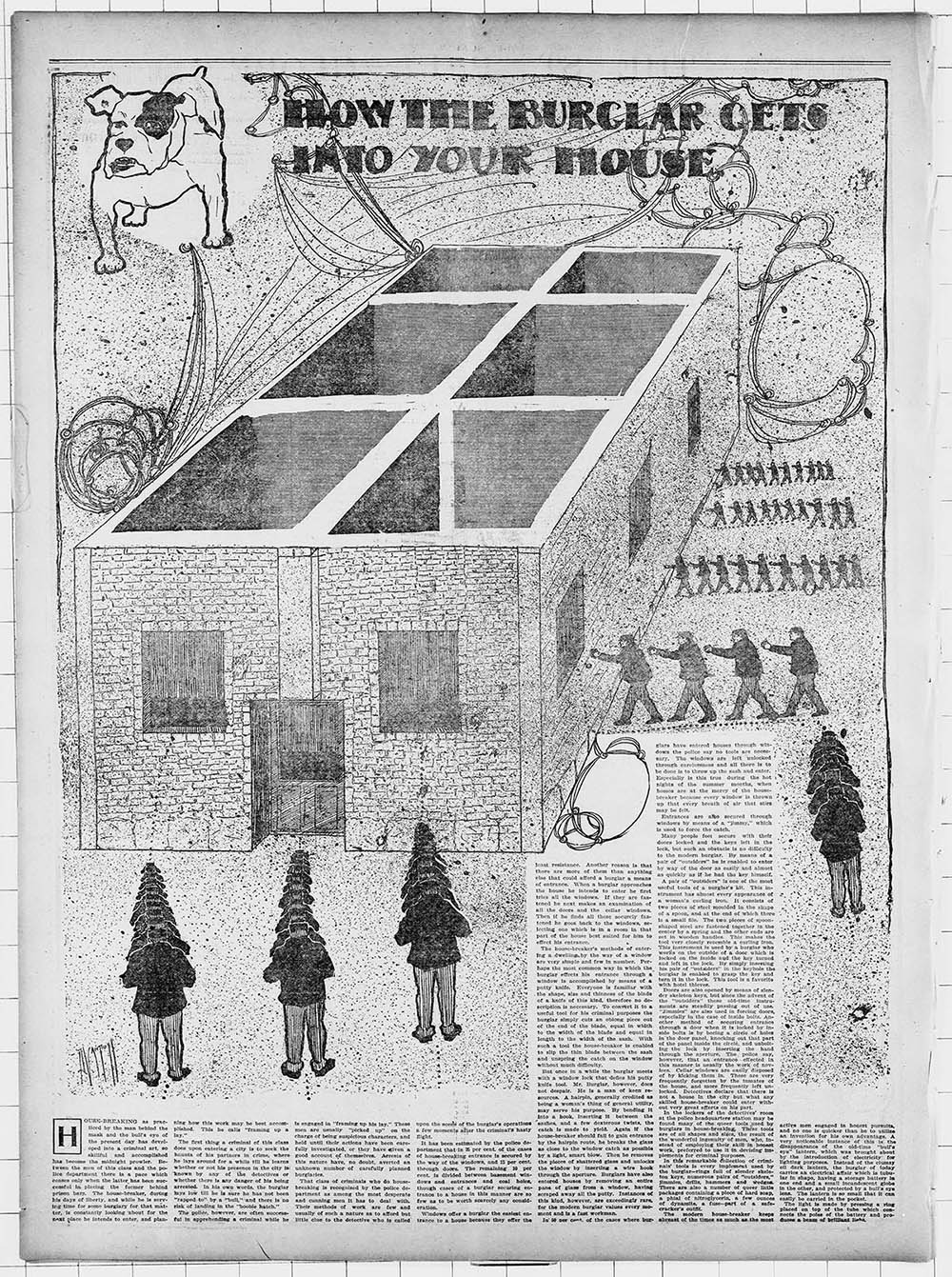

Hacked Homes, Gas Attacks, and Panic Room Design

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via The Saint Paul Globe].

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via The Saint Paul Globe].

One unfortunate side-effect of the Greek financial crisis has been a rise in domestic burglaries. This has been inspired not only by a desperate response to bad economic times, but by the fact that many people have withdrawn their cash from banks and are now storing their cash at home.

As The New York Times reported at the end of July, “in the weeks before capital controls were imposed at the end of June, billions of euros fled the Greek banking system. Greeks feared that their euro deposits might be automatically converted to a new currency if Greece left the eurozone and would quickly lose value, or that they would face a ‘haircut’ to their accounts if their bank failed amid the stresses of the crisis.”

This had the effect that, while the rich simply shifted their assets overseas or into Swiss bank accounts, “the middle class has stashed not just cash but gold and jewelry, among other valuables, under the proverbial mattress.” Now, however, those “hidden valuables had become enticing targets for thieves.”

Or, more accurately, for burglars.

Burglary is a spatial crime: its very definition requires architecture. By entering an architectural space, whether it’s a screened-in porch or a megamansion, theft or petty larceny becomes burglary, a spatially defined offense that cannot take place without walls and a roof.

[Image: A street in Athens, via Wikipedia].

[Image: A street in Athens, via Wikipedia].

In any case, while Greece sees its burglary rate go up and reports of local break-ins rise, home fortification has also picked up pace. “Many apartment doors have sprouted new security locks with heavy metal plates, similar to the locks used in safes,” we read, and razor wire now “bristles from garden gates where there were none last summer.”

This vision of DIY security measures applied to high-rise residential towers and other housing blocks in Athens is a surprising one, considering that, globally, burglary is in such decline that The Economist ran an article a few years ago asking, “Where have all the burglars gone?”

As it happens, I’ve been studying burglary for the past few years for many reasons; among those is the fact that burglary offers insights into otherwise overlooked possibilities for reading and navigating urban and architectural space.

Indeed, burglary’s architectural interest comes not from its ubiquity, but from its unexpected, often surprisingly subtle misuse of the built environment. Burglars approach buildings differently, often seeking modes of entry other than doors and approaching buildings—whole cites—as if they’re puzzles waiting to be solved or beaten.

Consider the recent case of Formula 1 driver Jenson Button, whose villa in the south of France was broken into; the burglars allegedly made their entrance after sending anesthetic gas through the home’s air-conditioning system, incapacitating Button and his wife.

Although the BBC reports some convincing skepticism about Button’s claim, Button’s own spokesperson insists that this method of entry is on the rise: “The police have indicated that this has become a growing problem in the region,” the spokesperson said, “with perpetrators going so far as to gas their proposed victims through the air conditioning units before breaking in.”

There are other supposed examples of this sort of attack. Also from the BBC:

Former Arsenal footballer Patrick Vieira said he and his family were knocked out by gas during a 2006 raid on their home in Cannes. And in 2002, British television stars Trinny Woodall and Susannah Constantine said they were gassed while attending the Cannes Film Festival.

Other accounts, particularly from France, have appeared in the media over the past 15 years or so, describing people waking up groggy to discover they slept through a raid.

It’s worth noting, on the other hand, that actual proof of these home gas attacks is lacking; what’s more, the amount of anesthetic needed to knock out multiple adults in a large architectural space is prohibitively expensive to obtain and also presents a high risk of explosion.

Nonetheless, a security firm called SRX has commented on the matter, saying to the BBC that this is a real risk and even pointing out the specific vulnerability: ventilation intake fans usually found on the perimeter of a property, where they can be visually and acoustically shielded in the landscaping.

Their very inconspicuousness also “makes them ideal for burglars,” however, as homeowners can neither see nor hear if someone is tampering with them; as SRX points out, “we have to try and prevent access to those fans.”

Fortified air-conditioning intake fans. Razor wire defensive cordons on urban balconies. Reinforced front doors like something you’d find on a safe or vault.

[Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via Wikipedia].

[Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via Wikipedia].

The subject of burglary, break-ins, and home fortification interests me enough that I’ve written an entire book about it—called A Burglar’s Guide to the City, due out next spring from FSG—but it is also something I’ve addressed in an ongoing three-part series about domestic home security for Dwell magazine.

The second of those three articles is on newsstands now in the September 2015 issue, and it looks at the design and installation of safe rooms, more popularly known as panic rooms.

That article is not yet online—I’ll add a link when it’s up—but it includes interviews with safe room design experts on both U.S. coasts, as well as some interesting anecdotes about trends in home fortification, such as installing “lead-lined sheetrock to protect against radioactive attack.” Bullet-proof doors, rocket-propelled grenades, and home biometric security systems all make an unsettling appearance, as well.

Prior to that, in the July/August 2015 issue, I looked at technical vulnerabilities in smart home design. There, among other things, you can read that the “$20,000 smart-home upgrade you just paid for? It can now be nullified for about $400,” using a wallet-size device engineered by Drew Porter of Red Mesa.

Further, you’ll learn how “specific combinations of remote-control children’s toys could be hacked by ambitious burglars to do everything from watching you leave on your next vacation to searching your home for hidden valuables.” That’s all available online.

The final article in that three-part series comes out in the October 2015 issue. Check them all out, if you get a chance, and then don’t forget to pick up a copy of A Burglar’s Guide to the City next spring.

Subterranean Lightning Brigade

[Image: “Riggers install a lightning rod” atop the Empire State Building “in preparation for an investigation into lightning by scientists of the General Electric Company” (1947), via the Library of Congress].

[Image: “Riggers install a lightning rod” atop the Empire State Building “in preparation for an investigation into lightning by scientists of the General Electric Company” (1947), via the Library of Congress].

This is hardly news, but I wanted to post about the use of artificial lightning as a navigational aid for subterranean military operations.

This was reported at the time as a project whose goal was “to let troops navigate about inside huge underground enemy tunnel complexes by measuring energy pulses given off by lightning bolts,” where those lightning bolts could potentially be generated on-demand by aboveground tactical strike teams.

Such a system would replace the use of GPS—whose signals cannot penetrate into deep subterranean spaces—and it would operate by way of sferics, or radio atmospheric signals generated by electrical activity in the sky.

The proposed underground navigational system—known as “Sferics-Based Underground Geolocation” or S-BUG—would be capable of picking up these signals even from “hundreds of miles away. Receiving signals from lighting strikes in multiple directions, along with minimal information from a surface base station also at a distance, could allow operators to accurately pinpoint their position.” They could thus maneuver underground, even in hundreds—thousands—of feet below the earth’s surface in enemy caves or bunkers.

Hundreds of miles is a very wide range, of course—but what if there is no natural lightning in the area?

Enter artificial military storm generators, or the charge of the lightning brigade.

Back in 2009, DARPA also put out of a request for proposals as part of something called Project Nimbus. NIMBUS is “a fundamental science program focused on obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the lightning process.” However, it included a specific interest in developing machines for “triggering lightning”:

Experimental Set-up for Triggering Lightning: Bidders should fully describe how they would attempt to trigger lightning and list all potential pieces of equipment necessary to trigger lightning, as well as the equipment necessary to measure and characterize the processes governing lightning initiation, propagation, and attachment.

While it’s easy enough to wax conspiratorial here about future lightning weapons or militarized storm cells—after all, DARPA themselves write that they want to understand “how [lightning] ties into the global charging circuit,” as if “the global charging circuit” is something that could be instrumentalized or controlled—I actually find it more interesting to speculate that generating lightning would be not for offensive purposes at all, but for guiding underground navigation.

[Image: Lightning storm over Boston; via Wikimedia/NOAA].

[Image: Lightning storm over Boston; via Wikimedia/NOAA].

Something akin to a strobe light begins pulsing atop a small camp of unmarked military vehicles parked far outside a desert city known for its insurgent activities. These flashes gradual lengthen, both temporally and physically, lasting longer and stretching upward into the sky; the clouds above are beginning to thicken, grumbling with quiet rolls of thunder.

Then the lightning strikes begin—but they’re unlike any natural lightning you’ve ever seen. They’re more like pops of static electricity—a pulsing halo or toroidal crown of light centered on the caravan of trucks below—and they seem carefully timed.

To defensive spotters watching them through binoculars in the city, it’s obvious what this means: there must be a team of soldiers underground somewhere, using artificial sferics to navigate. They must be pushing forward relentlessly through the sewers and smuggling tunnels, crawling around the roots of buildings and maneuvering through the mazework of infrastructure that constitutes the city’s underside, locating themselves by way of these rhythmic flashes of false lightning.

Of course, this equipment would eventually be de-militarized and handed down to the civilian sector, in which case you can imagine four friends leaving REI on a Friday afternoon after work with an artificial lightning generator split between them; no larger than a camp stove, it would eventually be set up with their other weekend caving equipment, used to help navigate through deep, stream-slick caves an hour and a half outside town, beneath tall mountains where GPS can’t always be trusted.

Or, perhaps fifty years from now, salvage teams are sent deep into the flooded cities of the eastern seaboard to look for and retrieve valuable industrial equipment. They install an artificial lightning unit on the salt-bleached roof of a crumbling Brooklyn warehouse before heading off in a small armada of marsh boats, looking for entrances to old maintenance facilities whose basement storage rooms might have survived rapid sea-level rise.

Disappearing down into these lost rooms—like explorers of Egyptian tombs—they are guided by bolts of artificial lightning that spark upward above the ruins, reflected by tides.

[Image: Lightning via NOAA].

[Image: Lightning via NOAA].

Or—why not?—perhaps we’ll send a DARPA-funded lightning unit to one of the moons of Jupiter and let it flash and strobe there for as long as it needs. Called Project Miller-Urey, its aim is to catalyze life from the prebiotic, primordial soup of chemistry swirling around there in the Cthulhoid shadow of eternal ice mountains.

Millions and millions of years hence, proto-intelligent lifeforms emerge, never once guessing that they are, in fact, indirect descendants of artificial lightning technology. Their spark is not divine but military, the electrical equipment that sparked their ancestral line long since fallen into oblivion.

In any case, keep your eyes—and cameras—posted for artificial lightning strikes coming to a future military theater near you…

From Guns, Bridges

[Image: An otherwise unrelated shot of rebar used in road construction; via Wikipedia].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated shot of rebar used in road construction; via Wikipedia].

A quick news item from last month seems worth mentioning: “approximately 3,400 confiscated firearms” are being melted down and turned into rebar to be used for bridge and highway construction projects throughout the American Southwest.

As Global Construction Review reported, “The weapons will be melted into steel reinforcing bar, better known as ‘rebar,’ and transformed into elements of construction for upgrades in freeways and bridges in Arizona, California and Nevada.”

The event where this occurs is known as the “annual gun-melt,” and its future byproducts will be coming soon to a highway crossing near you: former armaments, from swords to plowshares, embedded in our everyday landscape.

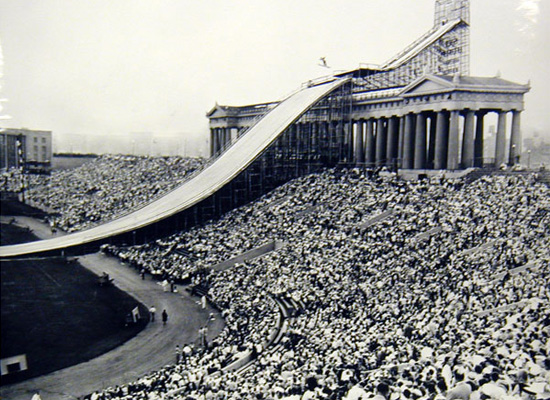

Joyful Rendezvous Upon Pure Ice and Snow

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

The 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing are something of a moonshot moment for artificial snow-making technology: the winter games will be held “in a place with no snow.” That’s right: “the 2022 Olympics will rely entirely on artificial snow.”

As a report released by the International Olympic Committee admits, “The Zhangjiakou and Yanqing Zones have minimal annual snowfall and for the Games would rely completely on artificial snow. There would be no opportunity to haul snow from higher elevations for contingency maintenance to the racecourses so a contingency plan would rely on stockpiled man-made snow.”

This gives new meaning to the word snowbank: a stock-piled reserve of artificial landscape effects, an archive of on-demand, readymade topography.

Beijing’s slogan for their Olympic bid? “Joyful Rendezvous upon Pure Ice and Snow.”

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

Purely in terms of energy infrastructure and freshwater demand—most of the water will be pumped in from existing reservoirs—the 2022 winter games will seemingly be unparalleled in terms of their sheer unsustainability. Even the IOC sees this; from their report:

The Commission considers Beijing 2022 has underestimated the amount of water that would be needed for snowmaking for the Games but believes adequate water for Games needs could be supplied.

In addition, the Commission is of the opinion that Beijing 2022 has overestimated the ability to recapture water used for snowmaking. These factors should be carefully considered in determining the legacy plans for snow venues.

Knowing all this, then, why not be truly radical—why not host the winter games in Florida’s forthcoming “snowball fight arena,” part of “a $309 million resort near Kissimmee that would include 14-story ski and snowboard mountain, an indoor/outdoor skateboard park and a snowball fight arena”?

Why not host them in Manaus?

Interestingly, the IOC also raises the question of the Games’ aesthetics, warning that the venues might not really look like winter.

“Due to the lack of natural snow,” we read, “the ‘look’ of the venue may not be aesthetically pleasing either side of the ski run. However, assuming sufficient snow has been made or stockpiled and that the temperature remains cold, this should not impact the sport during the Games.”

Elsewhere: “There could be no snow outside of the racecourse, especially in Yanqing, impacting the visual perception of the snow sports setting.” This basically means that there will be lots of bare ground, rocks, and gravel lining the virginal white strips of these future ski runs.

[Image: Ski jumping in summer at Chicago’s Soldier Field (1954); via Pruned].

[Image: Ski jumping in summer at Chicago’s Soldier Field (1954); via Pruned].

Several years ago, Pruned satirically offered Chicago as a venue for the world’s “first wholly urban Winter Olympics.” With admirable detail, he went into many of the specifics for how Chicago might pull it off, but he also points out the potential aesthetic disorientation presented by seeing winter sports in a non-idyllic landscape setting.

“Chicago’s gritty landscape shouldn’t be much of a handicap,” he suggests. Chicago might not “embody a certain sort of nature—rustic mountains, pastoral evergreen forests, a lonely goatherd, etc.,” but the embedded landscape technology of the Winter Games should have left behind that antiquated Romanticism long ago.

As Pruned asks, “have the more traditional Winter Olympic sites not been over the years transformed into high-tech event landscapes, carefully managed and augmented with artificial snow and heavy plows that sculpt the slopes to a pre-programmed set of topographical parameters?”

Seen this way, Beijing’s snowless winter games are just an unsustainable historical trajectory taken to its most obvious next step.

[Image: Making snow for It’s A Wonderful Life, via vintage everyday].

[Image: Making snow for It’s A Wonderful Life, via vintage everyday].

In any case, the 2022 Winter Olympics are shaping up to be something like an Apollo Program for fake snow, an industry that, over the next seven years, seems poised to experience a surge of innovation as the unveiling of this most artificial of Olympic landscapes approaches.

Landscapes of Inevitable Catastrophe

[Image: Illustration by David McConochie, courtesy of The Art Market, via The Guardian].

[Image: Illustration by David McConochie, courtesy of The Art Market, via The Guardian].

Last month, The Economist reported on the widespread presence of radioactive tailings piles—waste rock left over from Soviet mining operations—in southern Kyrgyzstan. Many of the country’s huge, unmonitored mountains of hazardous materials are currently leaching into the local water supply.

In a particularly alarming detail, even if you wanted to avoid the danger, you might not necessarily know where to find it: “Fences and warning signs have been looted for scrap metal,” we read.

Frequent landslides and seasonal floods also mean that the tailings are at risk of washing downriver into neighboring countries, including into “Central Asia’s breadbasket, the Fergana Valley, which is home to over 10m people… A European aid official warns of a ‘creeping environmental disaster.'”

Attempts at moving the piles have potentially made things worse, releasing “radioactive dust” that might be behind a spike in local cancers.

In addition to the sheer aesthetic horror of the landscape—a partially radioactive series of river valleys, lacking in warning signs, that writer Robert Macfarlane would perhaps call “eerie,” a place where “suppressed forces pulse and flicker beneath the ground and within the air… waiting to erupt or to condense”—it’s worth noting at least two things:

One, there appears to be no end in sight; as The Economist points out, the neighboring countries “are hardly on speaking terms, so cross-border co-operation is non-existent,” and the costs of moving highly contaminated mine waste are well out of reach for the respective governments.

This means we can more or less confidently predict that, over the coming decades, many of these tailings piles will wash away, slowly but relentlessly, fanning out into the region’s agricultural landscape.

Once these heavy metals and flecks of uranium have dispersed into the soil, silt, and even plantlife, they will be nearly impossible to re-contain; this will have effects not just over the span of human lifetimes but on a geological timescale.

Second, most of these piles are unguarded: unwatched, unmonitored, unsecured. They contain radioactive materials. They are in a region known for rising religious extremism.

Given all this, surely finding a solution here is rather urgent, before these loose mountains of geological toxins assume an altogether more terrifying new role in some future news cycle—at which point, in retrospect, articles like The Economist‘s will seem oddly understated.

[Image: Hand-painted radiation sign at Chernobyl, via the BBC].

[Image: Hand-painted radiation sign at Chernobyl, via the BBC].

Indeed, our ability even to comprehend threats posed on a geologic timescale—let alone to act on those threats politically—is clearly not up to the task of grappling with events or landscapes such as these.

To go back to Robert Macfarlane, he wrote another article earlier this year about the specialized vocabulary that has evolved for naming, describing, or cataloging terrestrial phenomena. By contrast, he suggests, we now speak with “an impoverished language for landscape” in an era during when “a place literacy is leaving us.”

As Macfarlane writes, “we lack a Terra Britannica, as it were: a gathering of terms for the land and its weathers—terms used by crofters, fishermen, farmers, sailors, scientists, miners, climbers, soldiers, shepherds, poets, walkers and unrecorded others for whom particularised ways of describing place have been vital to everyday practice and perception.”

Channeling Macfarlane, where is the vocabulary—where are our cognitive templates—for describing and understanding these landscapes of long-term danger and slow catastrophe?

It often seems that we can stare directly into the wasteland without fear, not because there is nothing of risk there, but because our own words simply cannot communicate the inevitability of doom.

Horse Skull Disco

[Image: Horse skull via Wikimedia].

[Image: Horse skull via Wikimedia].

If you’re looking to install a new sound system in your house, consider burying a horse skull in the floor.

According to the Irish Archaeological Consultancy, the widespread discovery of “buried horse skulls within medieval and early modern clay floors” has led to the speculation that they might have been placed there for acoustic reasons—in other words, “skulls were placed under floors to create an echo,” we read.

Ethnographic data from Ireland, Britain and Southern Scandinavia attests to this practice in relation to floors that were in use for dancing. The voids within the skull cavities would have produced a particular sound underfoot. The acoustic skulls were also placed in churches, houses and, in Scandinavia especially, in threshing-barns… It was considered important that the sound of threshing carried far across the land.

They were osteological subwoofers, bringing the bass to medieval villages.

It’s hard to believe, but this was apparently a common practice: “the retrieval of horse skulls from clay floors, beneath flagstones and within niches in house foundations, is a reasonably widespread phenomenon. This practice is well attested on a wider European scale,” as well, even though the ultimate explanation for its occurrence is still open to debate (the Irish Archaeological Consultancy post describes other interpretations, as well).

Either way, it’s interesting to wonder if the thanato-acoustic use of horse skulls as resonating gourds in medieval architectural design might have any implications for how natural history museums could reimagine their own internal sound profiles—that is, if the vastly increased reverberation space presented by skulls and animal skeletons could be deliberately cultivated to affect what a museum’s interior sounds like.

[Image: Inside the Paris Natural History Museum; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: Inside the Paris Natural History Museum; photo by Nicola Twilley].

Like David Byrne’s well-known project Playing the Building—”a sound installation in which the infrastructure, the physical plant of the building, is converted into a giant musical instrument”—you could subtly instrumentalize the bones on display for the world’s most macabre architectural acoustics.

(Via @d_a_salas. Previously on BLDGBLOG: Terrestrial Sonar).

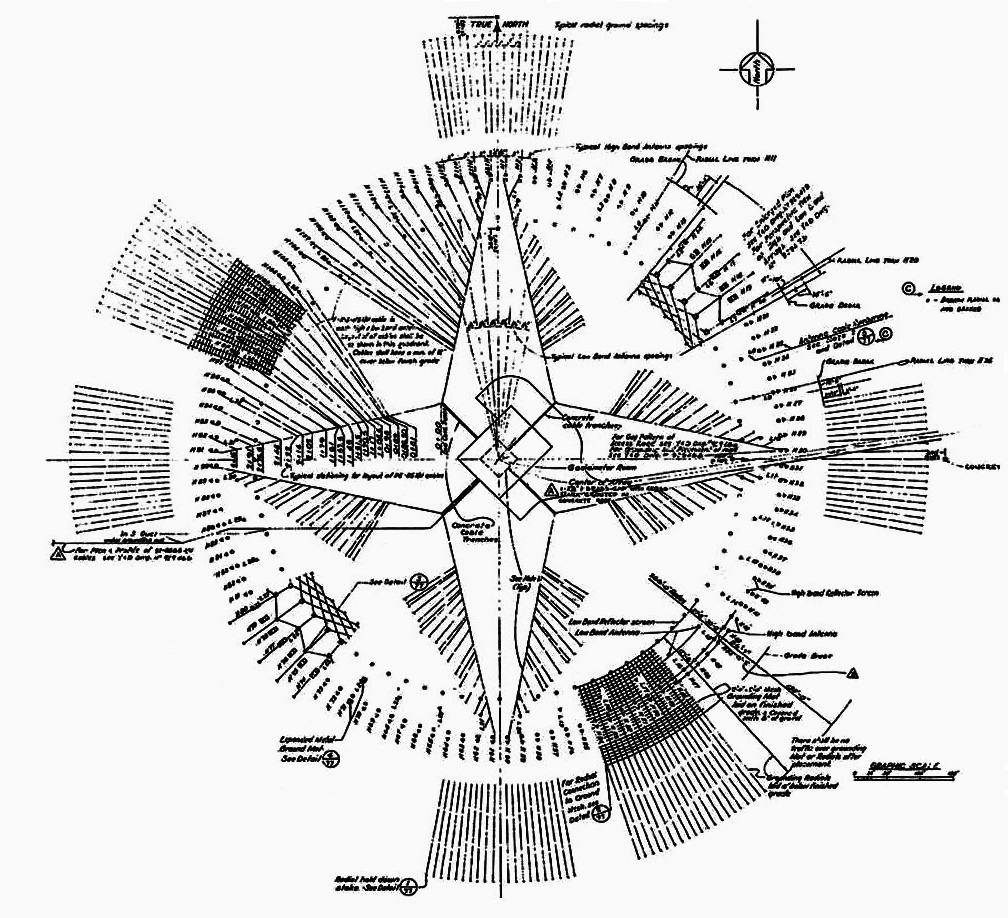

Full-Spectrum Mandala

[Image: Via the Pacific Cold War Patrol Museum].

[Image: Via the Pacific Cold War Patrol Museum].

Somewhat randomly—though I suppose I have a thing for antennas—I came across a blog post looking at the layout of Circularly Disposed Antenna Arrays.

A Circularly Disposed Antenna Array, he explains, was “sometimes referred to as a Circularly Disposed Dipole Array (CDDA)” and was “used for radio direction finding. The military used these to triangulate radio signals for radio navigation, intelligence gathering and search and rescue.”

[Image: Via the Pacific Cold War Patrol Museum].

[Image: Via the Pacific Cold War Patrol Museum].

While discussing the now-overgrown landscapes found on old military sites in Hawaii, the post’s author points out the remains of old antenna set-ups still visible in the terrain.

A series of photos, that you can find over at the original post, show how these abandoned circular land forms—like electromagnetic stone circles—exist just below the surface of the Hawaiian landscape, thanks to the archipelago’s intense militarization over the course of the 20th century.

He then cleverly juxtaposes these madala-like technical diagrams with what he calls a “Polynesian guidance system for navigating the Pacific” (bringing to mind our earlier look at large-scale weather systems in the South Pacific and how they might have guided human settlement there).

[Image: Via the Pacific Cold War Patrol Museum].

[Image: Via the Pacific Cold War Patrol Museum].

The idea that Polynesian shell map geometries and the antenna designs of Cold War-era military radio sites might inadvertently echo one another is hugely evocative, albeit purely a poetic analogy.

Finally, I couldn’t resist this brief passage, describing many of these ruined antenna sites: “Their exact Cold War era use, frequencies and purpose isn’t yet known but were most likely for aircraft radio navigation, direction finding, intelligence gathering and for search and rescue.”

You can all but picture the opening shots of a film here, as concerned military radio operators, surrounded by the arcane, talismanic geometries of antenna structures in the fading light of a Pacific summer evening, pick up the sounds of something vast and strange moving at the bottom of the sea.

Burglary & Rabies

People of Denver! If you are around next week, MCA Denver‘s legendary Mixed Taste series roars along with a new installment on Thursday, August 6, dedicated to “Burglary & Rabies.”

I’m proud to be representing the burglary part of the evening, discussing some behind-the-scenes tales and spatial research from my forthcoming book, A Burglar’s Guide to the City, due out in Spring 2016; Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy, co-authors of Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus, will be holding down the infectious vectors for the night’s darker half.

Rabies, Wasik and Murphy write, “is the most fatal virus in the world, a pathogen that kills nearly 100 percent of its hosts in most species, including humans.” Relentless and “like no other virus known to science, rabies sets its course through the nervous system, creeping upstream at one to two centimeters per day.”

However, seeing as one of the rules of Mixed Taste is that the speakers aren’t meant to reference one another’s themes—Mixed Taste consisting of “Tag Team Lectures on Unrelated Topics”—I’ll just leave it at that.

But please stop by if you’re in town: tickets are available here. I’ll be discussing everything from the geology of bank tunnels to roof jobs, LAPD helicopter flights to invisible architectural shapes perceptible only to lawyers.