[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

A gorgeous exhibition last year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art featured mechanical furniture designed by the father and son team, Abraham and David Roentgen: elaborate 18th-century technical devices disguised as desks and tables.

First, a quick bit of historical framing, courtesy of the Museum itself: “The meteoric rise of the workshop of Abraham Roentgen (1711–1793) and his son David (1743–1807) blazed across eighteenth-century continental Europe. From about 1742 to its closing in the early 1800s, the Roentgens’ innovative designs were combined with intriguing mechanical devices to revolutionize traditional French and English furniture types.”

Each piece, the Museum adds, was as much “an ingenious technical invention” as it was “a magnificent work of art,” an “elaborate mechanism” or series of “complicated mechanical devices” that sat waiting inside palaces and parlors for someone to come along and activate them.

If you can get past the visual styling of the furniture—after all, the dainty little details and inlays perhaps might not appeal to many BLDGBLOG readers—and concentrate instead only on the mechanical aspect of these designs, then there is something really incredible to be seen here.

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

Hidden amidst drawers and sliding panels are keyholes, the proper turning of which results in other unseen drawers and deeper cabinets popping open, swinging out to reveal previously undetectable interiors.

But it doesn’t stop there. Further surfaces split in half to reveal yet more trays, files, and shelves that unlatch, swivel, and slide aside to expose entire other cantilevered parts of the furniture, materializing as if from nowhere on little rails and hinges.

Whole cubic feet of interior space are revealed in a flash of clacking wood flung forth on tracks and pulleys.

As the Museum phrases it, Abraham Roentgen’s “mechanical ingenuity” was “exemplified by the workings of the lower section” of one of the desks on display in the show: “when the key of the lower drawer is turned to the right, the side drawers spring open; if a button is pressed on the underside of these drawers, each swings aside to reveal three other drawers.”

And thus the sequence continues in bursts of self-expansion more reminiscent of a garden than a work of carpentry, a room full of wooden roses blooming in slow motion.

[Images: Photos courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Images: Photos courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

The furniture is a process—an event—a seemingly endless sequence of new spatial conditions and states expanding outward into the room around it.

Each piece is a controlled explosion of carpentry with no real purpose other than to test the limits of volumetric self-demonstration, offering little in the way of useful storage space and simply showing off, performing, a spatial Olympics of shelves within shelves and spaces hiding spaces.

Sufficiently voluminous furniture becomes indistinguishable from a dream.

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

What was so fascinating about the exhibition—and this can be seen, for example, in some of the short accompanying videos (a few of which are archived on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website)—is that you always seemed to have reached the final state, the fullest possible unfolding of the furniture, only for some other little keyhole to appear or some latch to be depressed in just the right way, and the thing just keeps on going, promising infinite possible expansions, as if a single piece of furniture could pop open into endless sub-spaces that are eventually larger than the room it is stored within.

The idea of furniture larger than the space that houses it is an extraordinary topological paradox, a spatial limit-case like black holes or event horizons, a state to which all furniture makers could—and should—aspire, devising a Roentgen object of infinite volumetric density.

A single desk that, when unfolded, is larger than the building around it, hiding its own internal rooms and corridors.

Suggesting that they, too, were thrilled by the other-worldly possibilities of their furniture, the Roentgens—and I love this so much!—also decorated their pieces with perspectival illusions.

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Image: Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

The top of a table might include, for example, the accurately rendered, gridded space of a drawing room, as if you were peering cinematically into a building located elsewhere; meanwhile, pop-up panels might include a checkerboard reference to other possible spaces that thus seemed to exist somewhere within or behind the furniture, lending each piece the feel of a portal or visual gateway into vast and multidimensional mansions tucked away inside.

The giddiness of it all—at least for me—was the implication that you could decorate a house with pieces of furniture; however, when unfolded to their maximum possible extent, these same objects might volumetrically increase the internal surface area of that house several times over, doubling, tripling, quadrupling its available volume. But it’s not magic or the supernatural—it’s not quadraturin—it’s just advanced carpentry, using millimeter-precise joinery and a constellation of unseen hinges.

[Images: Photos courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Images: Photos courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art].

You could imagine, for example, a new type of house; it’s got a central service core lined with small elevators. Wooden boxes, perhaps four feet cubed, pass up and down inside the walls of the house, riding this network of dumbwaiters from floor to floor, where they occasionally stop, when a resident demands it. That resident then pops open the elevator door and begins to unfold the box inside, unlatching and expanding it outward into the room, this Roentgen object full of doors, drawers, and shelves, cantilevered panels, tabletops, and dividers.

And thus the elevators grow, simultaneously inside and outside, a liminal cabinetry both tumescent and architectural that fills up the space with spaces of its own, fractal super-furniture stretching through more than one room at a time and containing its own further rooms deep within it.

But then you reverse the process and go back through in the other direction, painstakingly shutting panels, locking drawers, pushing small boxes inside of larger boxes, and tucking it all up again, compressing it like a JPG back into the original, ultra-dense cube it all came from. You’re like some homebound god of superstrings tying up and hiding part of the universe so that others might someday rediscover it.

To have been around to drink coffee with the Roentgens and to discuss the delirious outer limits of furniture design would have been like talking to a family of cosmologists, diving deep into the quantum joinery of spatially impossible objects, something so far outside of mere cabinetry and woodwork that it almost forms a new class of industrial design. Alas, their workshop closed, their surviving objects today are limited in number, and the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is now closed.

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914].

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914]. [Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via Wikipedia].

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via Wikipedia].

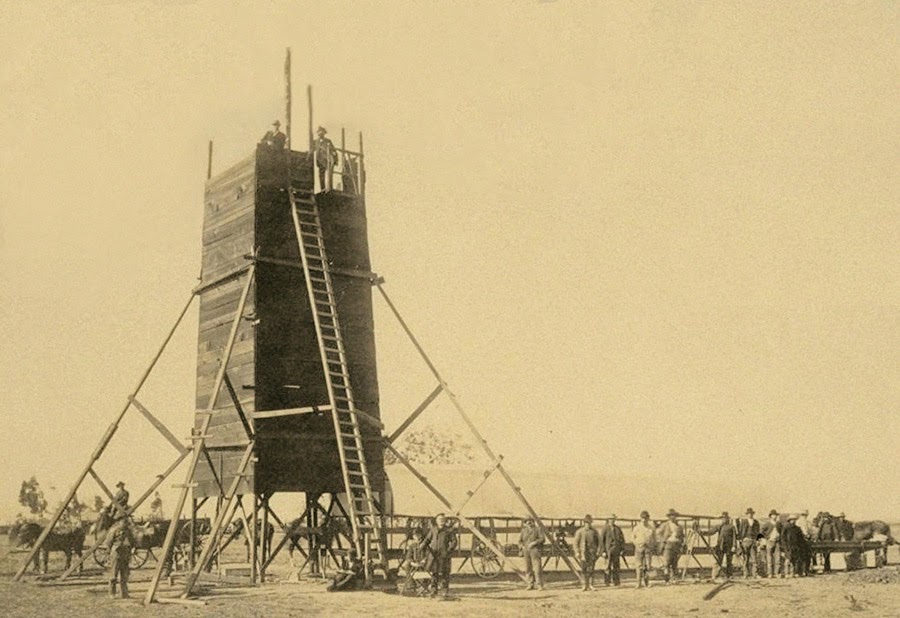

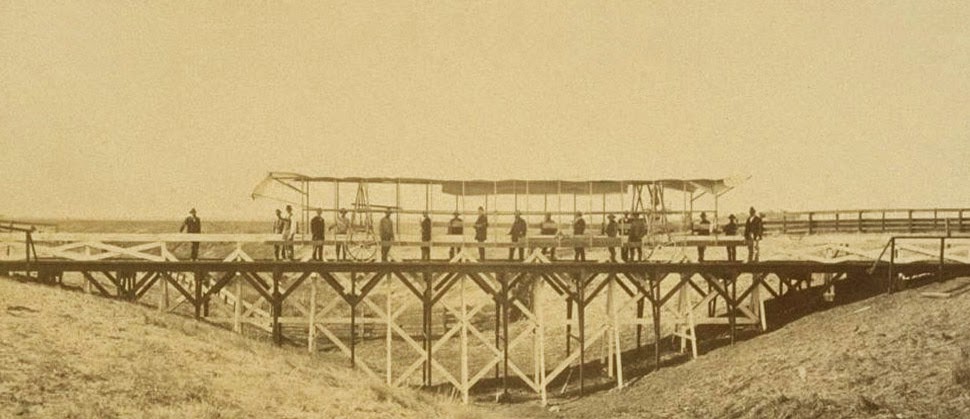

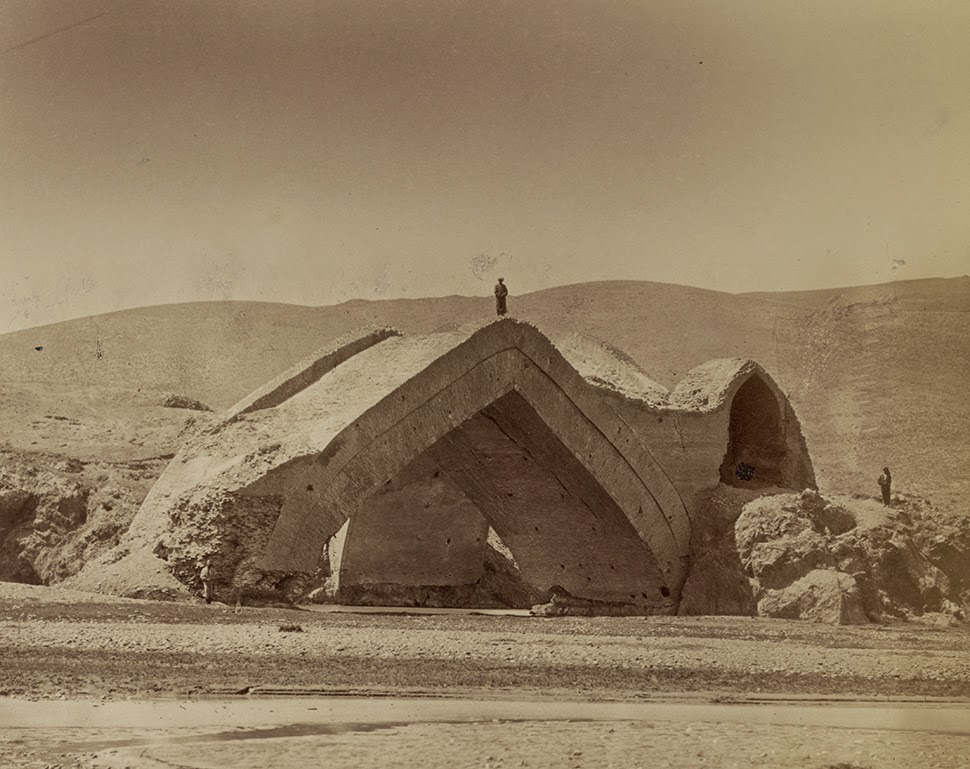

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.

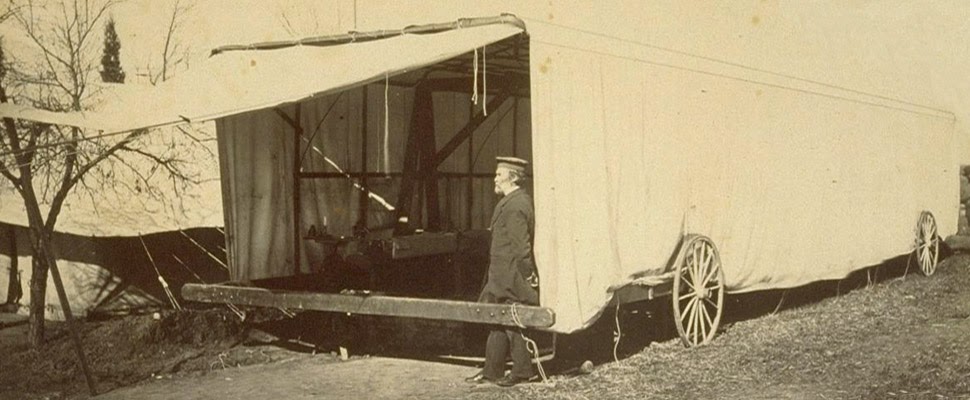

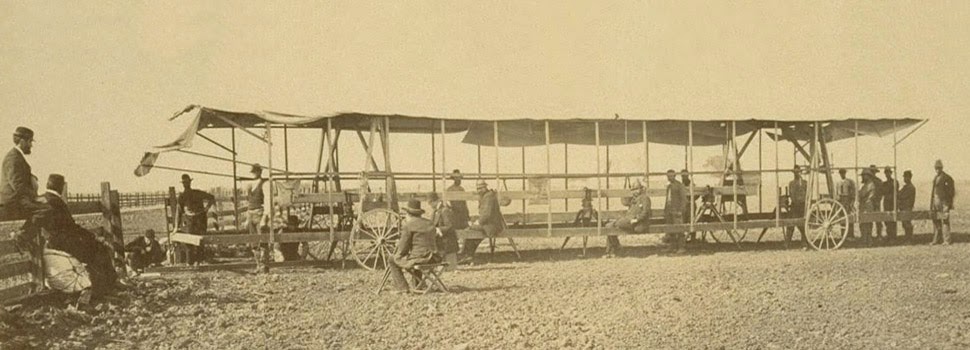

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.  The “moveable tent or ‘

The “moveable tent or ‘ The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the

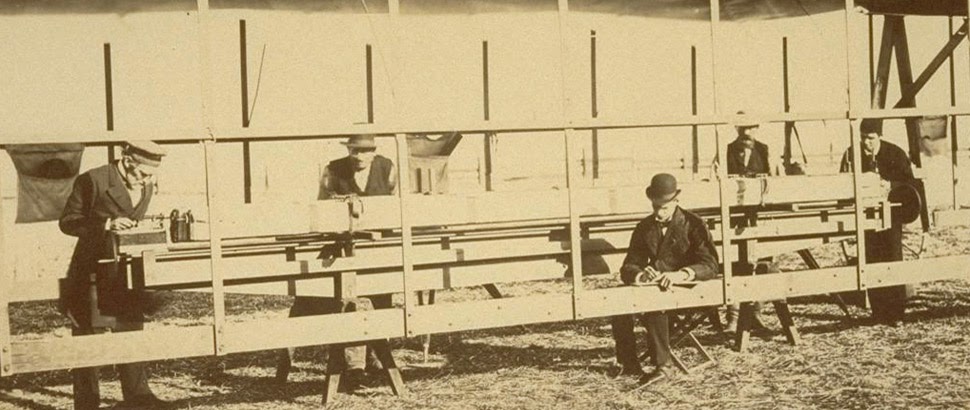

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the  In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.  That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land. Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

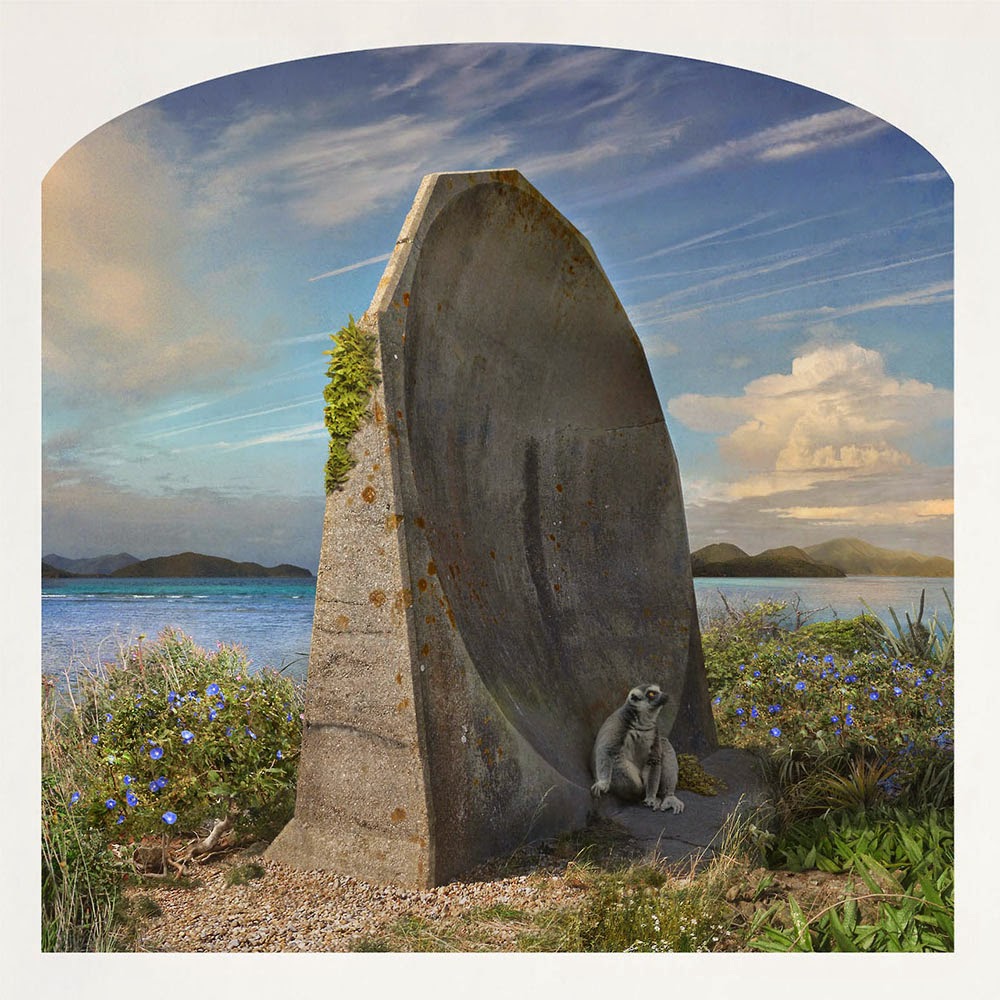

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy

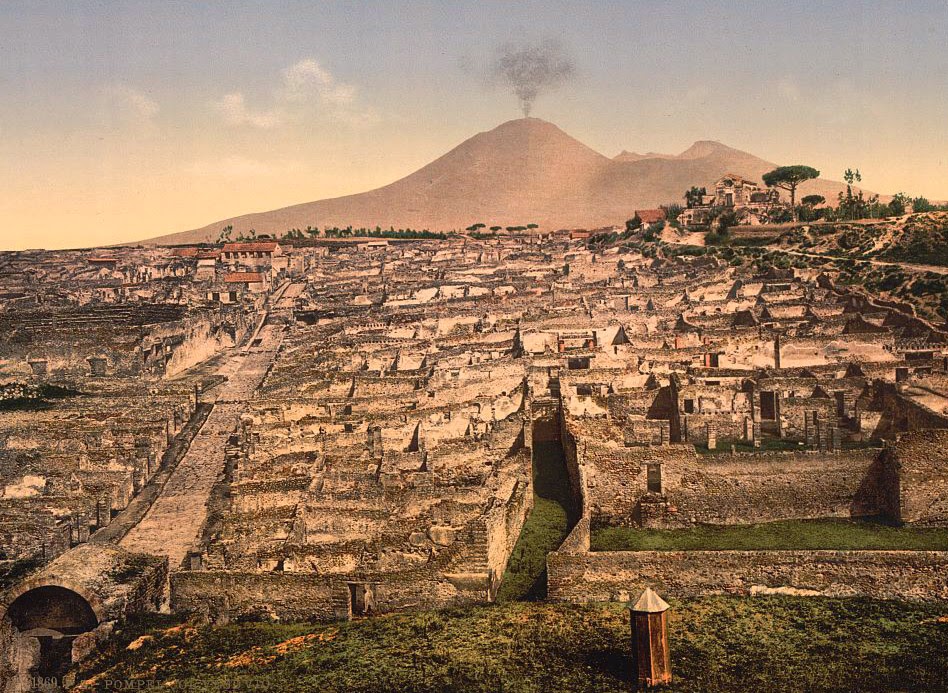

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy

[Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy  [Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Images: Photos courtesy of the

[Images: Photos courtesy of the  [Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Images: Photos courtesy of the

[Images: Photos courtesy of the  [Image: A Metropolitan Transportation Authority worker steps forward into the

[Image: A Metropolitan Transportation Authority worker steps forward into the

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: (top) Photo by

[Images: (top) Photo by