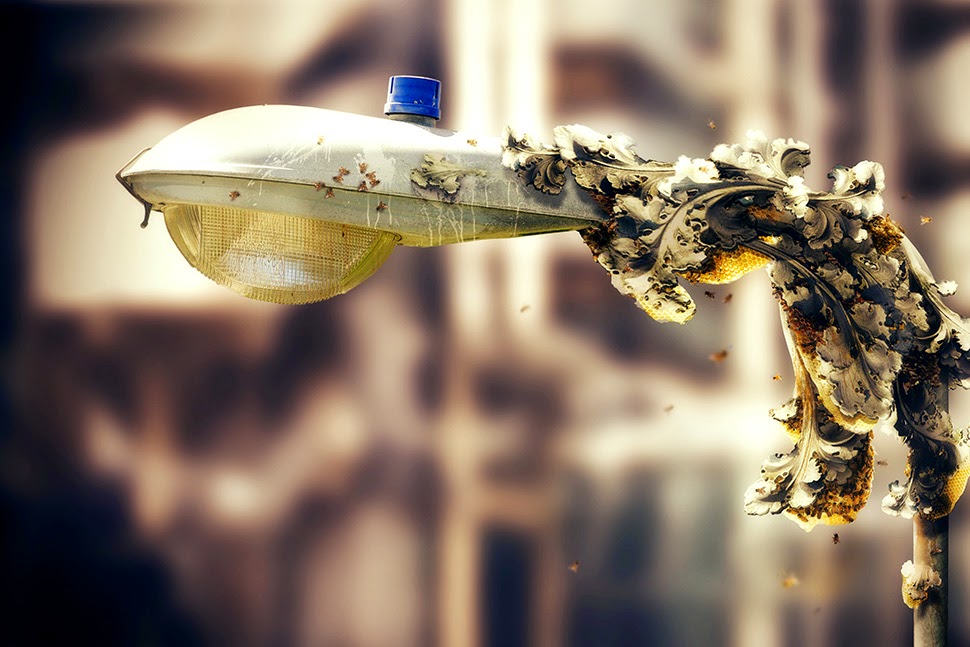

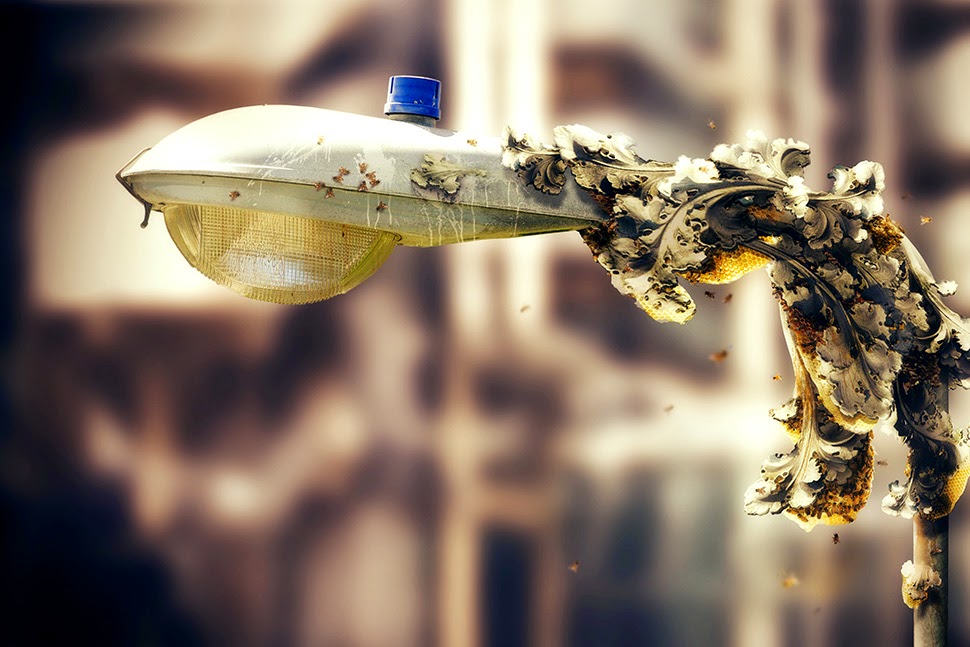

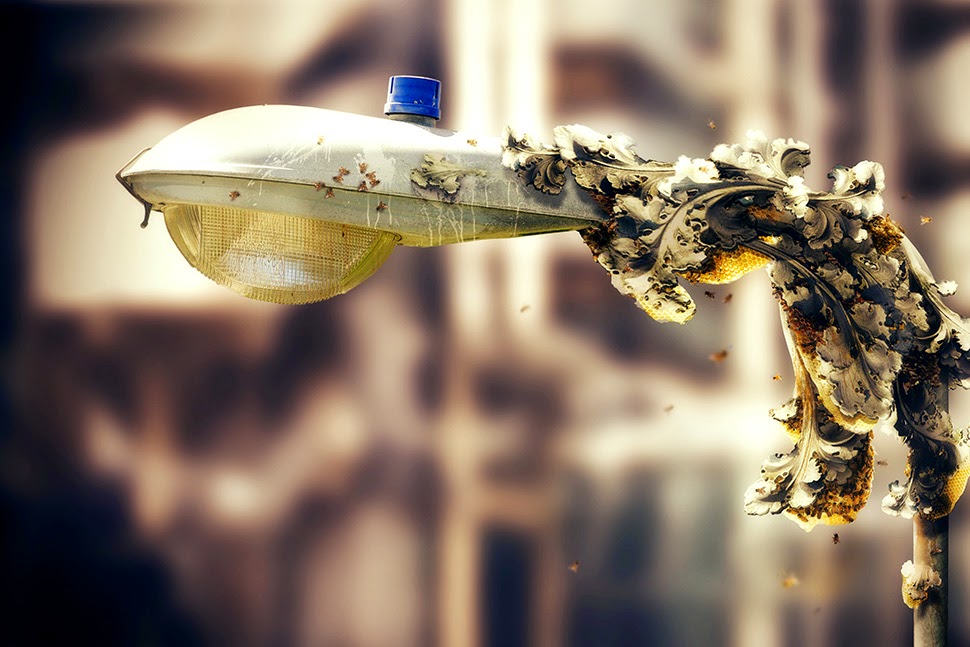

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

For thousands of years, animal bodies have been used as living 3D printers—or sentient printheads, we might say—but the range of possible material outputs is set to change quite radically. In fact, bioengineering is rapidly making this idea—that spiders, silkworms, and honeybees, to name just a few, are already 3D printers—more than just a poetic metaphor.

Those creatures are organic examples of depositional manufacturing, and they have been domesticated and used throughout human history for specific creative ends, whether it’s to produce something as mundane as honey or silk, or something far more outlandish, including automotive plastics, military armaments, and even concrete, as we’ll see below.

Animal Printheads

Researchers in Singapore discovered several years ago, for example, that silkworms fed a chemically peculiar diet could produce colored silk, readymade for use in textiles, as if they are actually biological ink cartridges; and other examples—in which animal bodies have been temporarily tweaked or even specifically bred to produce new, economically useful materials on a semi-industrial scale—are not hard to come by.

As it happens, for example, using bees as 3D printers is quickly becoming something of an accepted artistic process and its deep incorporation into advanced manufacturing processes will not be far behind.

Perhaps the most widely seen recent exploration of the animal-as-3D-printer concept was done last year for, of all things, a publicity stunt by Dewar’s, in which the company “3D printed” a bottle of Dewar’s using nothing but specially shaped and cultivated beehives.

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via designboom].

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via designboom].

These pictures tell the story clearly enough: using a large glass bottle as a mold in which the bees could create new hives, the process then ended with the removal of the glass and the revealing of a complete, bottle-shaped, “3D-printed” hive.

As Dewar’s joked, it was 3B-printed.

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via designboom].

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via designboom].

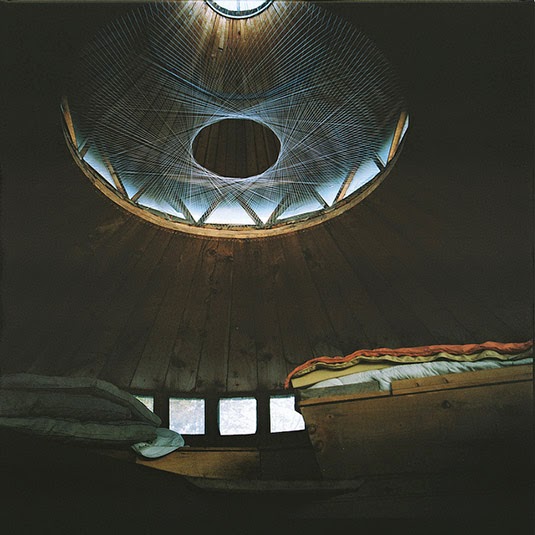

Or take the Silk Pavilion, another recent project you’ve undoubtedly already seen, in which researchers at MIT, led by architect Neri Oxman, 3D-printed a room-sized dome using carefully guided silkworms as living printheads.

[Image: Courtesy of MIT].

[Image: Courtesy of MIT].

The Silk Pavilion was an architectural experiment in which the body of the silkworm, guided along a series of very specific paths, was “deployed as a biological printer in the creation of a secondary structure.”

The primary structure, meanwhile—the pattern used by the silkworms as a kind of depositional substrate—was nothing more than a continuous thread wrapped around a metal scaffold like a labyrinth, seen in the image below.

[Image: Courtesy of MIT].

[Image: Courtesy of MIT].

It was at this point in the process that a “swarm of 6,500 silkworms was positioned at the bottom rim of the scaffold spinning flat non-woven silk patches as they locally reinforced the gaps across CNC-deposited silk fibers.” In other words, they infested the labyrinth and laid down architecture with their passing.

[Image: Courtesy of MIT].

[Image: Courtesy of MIT].

The “CNSilk” method, as it was known, resulted in a gossamer, woven dome that looks more like a cloud than a building.

[Images: Courtesy of MIT].

[Images: Courtesy of MIT].

What both of these examples demonstrate—despite the fact that one is a somewhat tongue-in-cheek media ploy by an alcohol company—is that animal bodies can, in fact, be guided, disciplined, or otherwise regulated to produce large-scale structures, from consumer objects to whole buildings.

After all, the very origins of architecture were a collaboration with animal bodies, and experiments like these only update those earliest constructions.

In both cases, however, the animals are simply depositing, or “printing,” what they would normally (that is, naturally, in the absence of human augmentation) produce: silk and honey. Things get substantially more interesting, on the other hand, when we look at more exotic biological materials.

Bee Plastic

For half a decade or more, materials scientist Debbie Chachra at New England’s Olin College of Engineering has been researching what’s known as “bee plastic”: a cellophane-like biopolymer produced by a species native to New England, called Colletes inaequalis.

These bees secrete tiny, cocoon-like structures in the soil—one such structure can be seen in the photo, below—using a special gland unique to its species. The resulting, non-fossil-fuel-based natural polyester not only resists biodegradation, it also survives the temperate extremes of New England, from the region’s sweltering summers to its subzero winter storms.

[Image: Courtesy of Deb Chachra].

[Image: Courtesy of Deb Chachra].

More intriguingly, however, the cellophane-like bee plastic “doesn’t come from petroleum,” Chachra explained to me for a 2011 end-of-year article in Wired UK. “The bees are pretty much just eating pollen and producing this plastic,” she continued, “and we’re trying to understand how they do it.”

Bee plastic, Chachra justifiably speculates, could perhaps someday be used to manufacture everything from office supplies to car bumpers, acting as an oil-free alternative to the plastics we use today. In the process, it could perhaps even kickstart a homegrown bio-industry for New England, where the species already thrives, wherein the very idea of a factory needs to be fundamentally reimagined.

The most exciting architectural possibilities here come less from the bees themselves and more from the elaborate structures that would be required to house their activities; imagine a brand new BMW factory somewhere in the suburbs of Boston populated only by plastic-producing bees, and you get some sense of where industrial manufacturing might go in an alternate future. Not unlike Dewar’s bee-printed bottle, then, augmented cousins of Chachra’s plastic-producing bees could thus 3D-print whole car bodies, kitchen counters, architectural parts, and other everyday products.

But even this, of course, is a vision of animal-based manufacturing that relies on the already-existent excretions of living creatures. Could we—temporarily putting aside the ethical implications of this, simply to discuss the material possibilities—perhaps genetically modify bees, silkworms, spiders, and so on to produce substantially more robust biopolymers, something not just strong enough to resist biodegrading but that could be produced and used on an industrial scale?

Recall, for example, that the U.S Army, working with a Canadian firm called Nexia Biotechnologies, was successful in its attempt to genetically engineer a goat that would produce spider-silk proteins in its milk. Incredibly, those “Biosteel goats,” as they were later known, were eventually housed in old ammunition bunkers on a New York State military base, as if they were living bioweapons that needed to be held in quarantine.

[Image: Biosteel goats summed-up in one simple equation (via)].

[Image: Biosteel goats summed-up in one simple equation (via)].

The ultimate goal of producing these goats was to generate an unbreakable super-fiber that could be used in battle gear, including “lightweight body armor made of artificial spider silk,” and other military armaments; but others have speculated that entire bridges or other pieces of urban infrastructure could someday be woven by goats.

These possibilities become even more strange and promising when we move to materials like concrete.

Concrete Honey

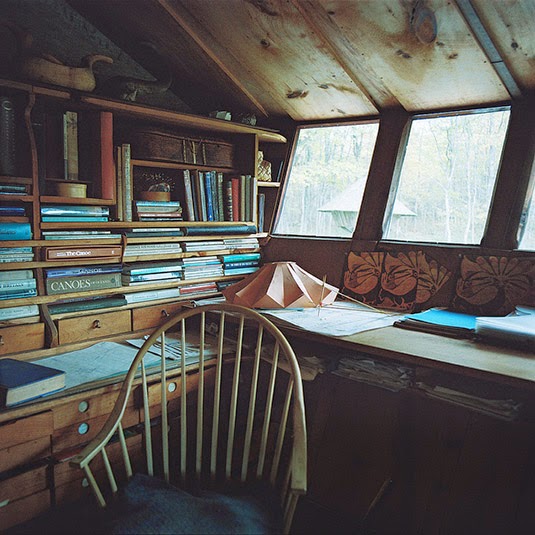

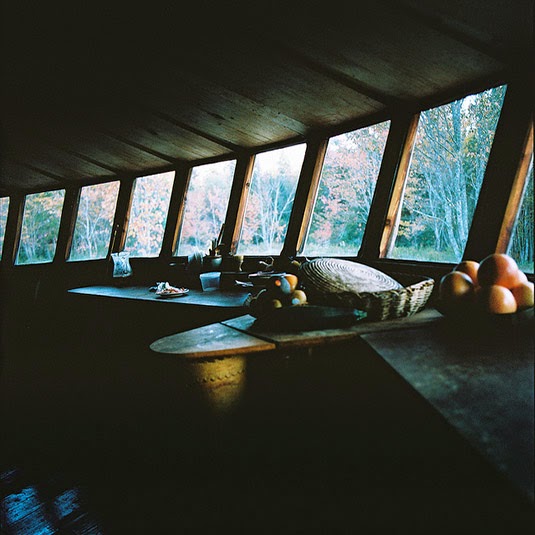

As part of an ongoing collaborative project, NYC-based designer John Becker and I have been looking at the possibility of using bees that have been genetically modified to print concrete. We could call them architectural printheads.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

Initially inspired by a somewhat willful misreading of a project published under the title “Bees Make Concrete Honey,” John and I began to imagine and illustrate a series of science-fictional scenarios in which a new urban bee species, called Apis caementicium—or cement bees—could be deployed throughout the city as a low-cost way to repair statues and fix architectural ornament, even to produce whole, free-standing structures, such as cathedrals.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

In a process not unlike that used for the Dewar’s bottle, above, the bees would be given an initial form to work within. Then, buzzing away inside this mold or cast, and additively depositing the ingredients for bio-concrete on the walls, frames, or structures they’ve been attached to, the bees could 3D-print new architectural forms into existence.

This includes, for example, the iconic stone lions found outside the New York Public Library; they’ve been damaged by exposure and human contact, but can now be fixed from within by concrete bees. Think this as a kind of organic caulking.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

Yet tidy plots such as these invariably spin out of control and things don’t quite go as planned.

Feral Printers

Predictably, these concrete bees eventually escape: first just a few here and there, but then an upstart colony takes hold elsewhere in the city. They breed, speciate, and expand.

Within a few years, as the bees reproduce and thrive, and as their increasingly far-flung colonies grow, people become aware of the scale of the problem: rogue 3D-printing bees have begun to infest the region.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

They print where they shouldn’t print and, without the direction of their carefully made formwork and molds, what they produce often makes no sense.

They print on signs and phone poles; they take over parks and gardens where they print strange forms on flowers, sealing orchids and roses in masonry shells. Bizarre gardens of hardened geometry form on windowsills and ledges, deep in urban forests and along railways and roads.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

Tiny fragments of concrete can soon be seen atop plants and door frames, beneath cars and on chain-link fences, coiling up and consuming the sides of structures where they were never meant to be, like kudzu; and, of course, strange bee bodies are found now and again, these little concrete-laden corpses lying in the deep grass of backyards, on parking lots and rooftops.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

Their fallen bodies, augmented and extraordinary, thus dot the very city they’ve also beautified and improved—this place where they once printed church steeples and apartment ornament, where they fixed cracked statues, sidewalks, and walls.

Of course, other, more adventurous or simply disoriented bees make their way further, hitching inadvertent rides in the holds of planes and cargo ships, mistakenly joining other hives then shipped around the world.

The bees are soon found in Europe, China, and—for reasons never quite clear to materials scientists—throughout India, where, as in the sample image below, they can be seen adding unnecessary ornamentation to temples in Rajasthan. Swarming and uncountable, they busily speck the outside of the building with bulbous and tumid additions no architect would ever have planned.

[Image: By John Becker].

[Image: By John Becker].

As the bees speciate yet further, and their concrete itself begins to mutate—in some cases, so hard it can only be removed by the toughest drills and demolition equipment, other times more like a slow-drying sandstone incapable of achieving any structure at all—this experiment in animal printheads, these living 3D printers producing architecture and industrial objects, comes to end.

A Bee Amidst The Machines

Most designers learn from the—in retrospect—obvious mistakes that led to these feral printers, returning to more easily controlled inorganic factories and industrial processes. But, even then, on quiet spring days, a tiny buzzing sound can occasionally be heard beneath someone’s front porch, out in the suburban gardens somewhere, deep inside National Parks, and even inside huge machines, where whole automobile assembly lines come shuddering to a halt.

There, within the gears, just doing what it’s used to doing—what we made it do—a tiny family of 3D-printing bees has taken root, leaving errant clumps of concrete wherever they alight.

(Thanks to John Becker for the fun. An earlier version of this post was previously published on Gizmodo).

[Image: Wrapped cabin, courtesy Sierra National Forest].

[Image: Wrapped cabin, courtesy Sierra National Forest].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The International Space Station,

[Image: The International Space Station,  [Image: The South Pacific “spacecraft cemetery”; image remade based on

[Image: The South Pacific “spacecraft cemetery”; image remade based on  [Image: The International Space Station, courtesy NASA].

[Image: The International Space Station, courtesy NASA].

[Image: An entrance to the quarry in Kanne; photo by

[Image: An entrance to the quarry in Kanne; photo by  [Images: Monks underground; via

[Images: Monks underground; via  The “streets” were named, but not always easy to follow; however, this didn’t stop officers stationed there from occasionally going out to explore the older tunnels at night. A former employee named Bob Hankinson describes how he used to navigate:

The “streets” were named, but not always easy to follow; however, this didn’t stop officers stationed there from occasionally going out to explore the older tunnels at night. A former employee named Bob Hankinson describes how he used to navigate:  [Image: An entrance into the NATO complex;

[Image: An entrance into the NATO complex;

[Image: Inside NYC’s

[Image: Inside NYC’s

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of  [Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of  [Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via  [Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via

[Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via

[Images: Courtesy of Dewar’s, via  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Images: Courtesy of

[Images: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of Deb Chachra].

[Image: Courtesy of Deb Chachra]. [Image: Biosteel goats summed-up in one simple equation (

[Image: Biosteel goats summed-up in one simple equation ( [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photo by

[Images: Photo by

[Images: Photo by

[Images: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by