[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

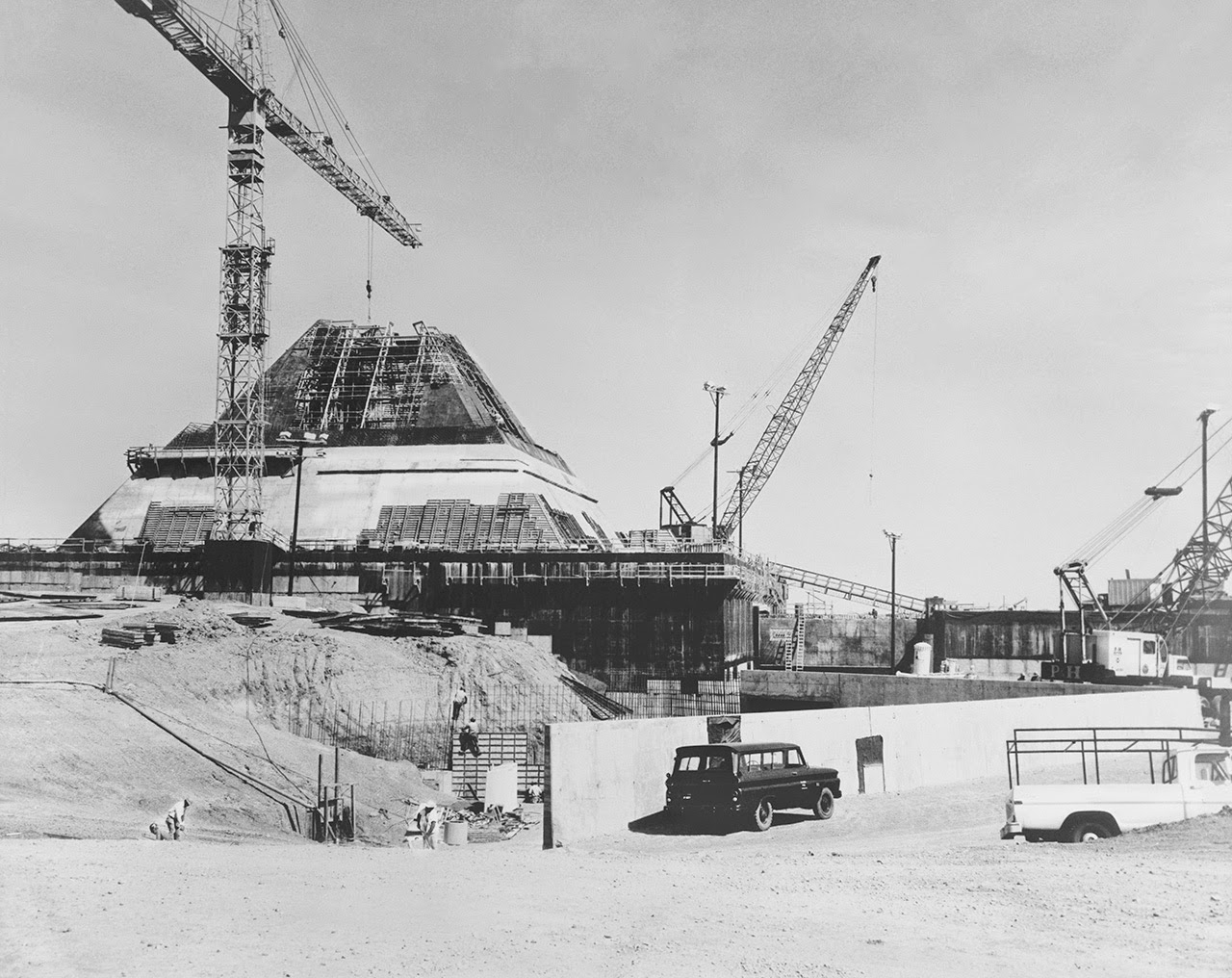

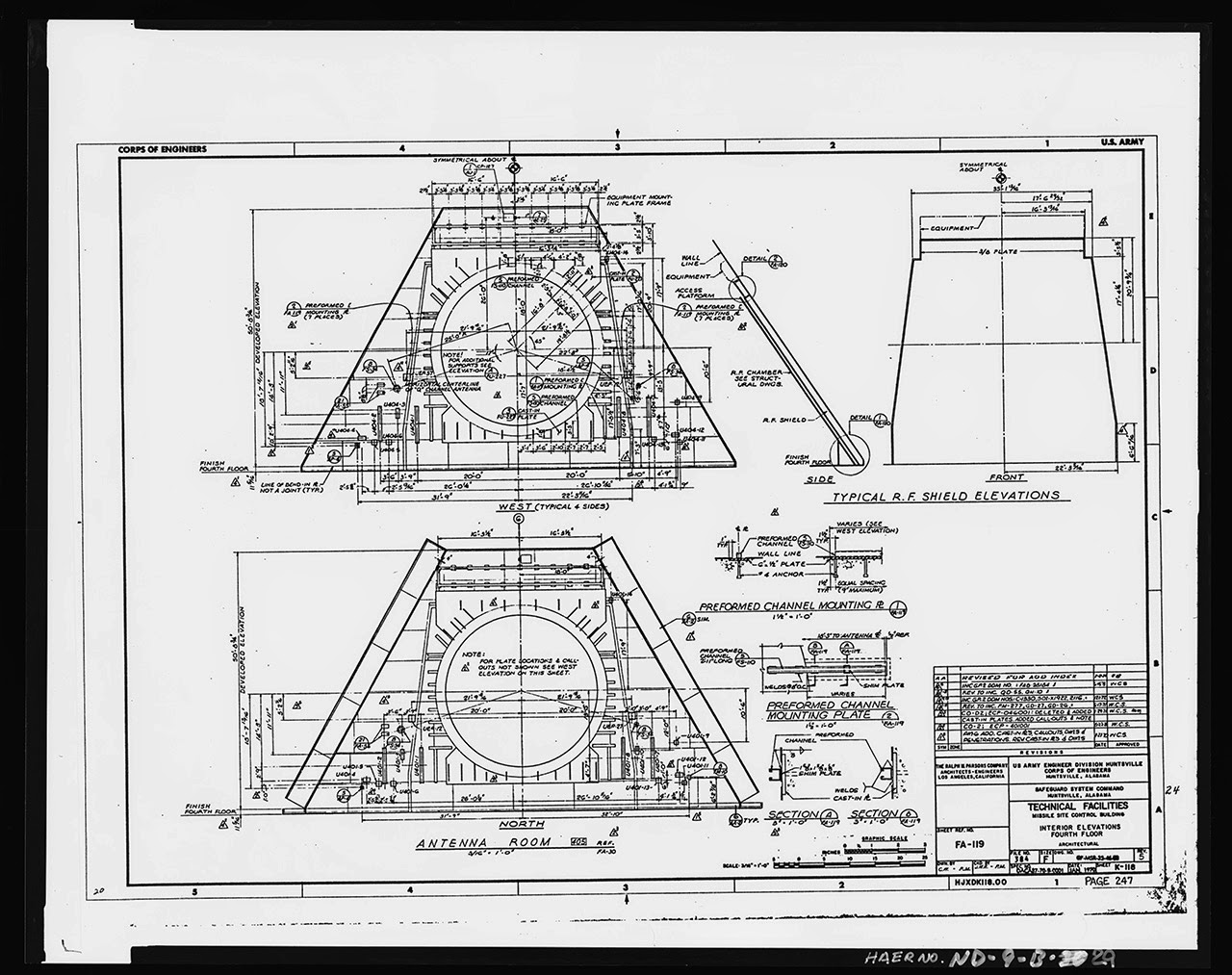

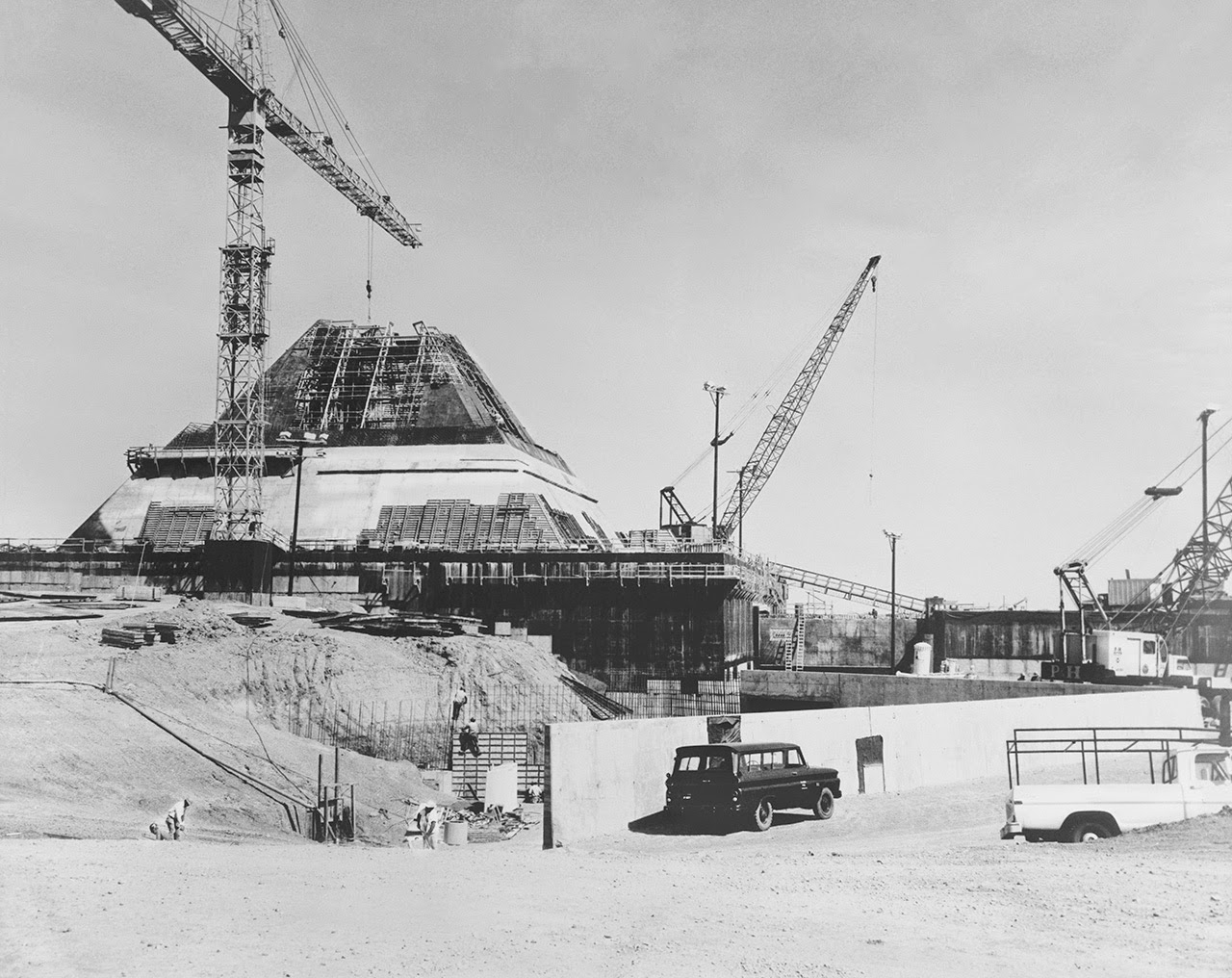

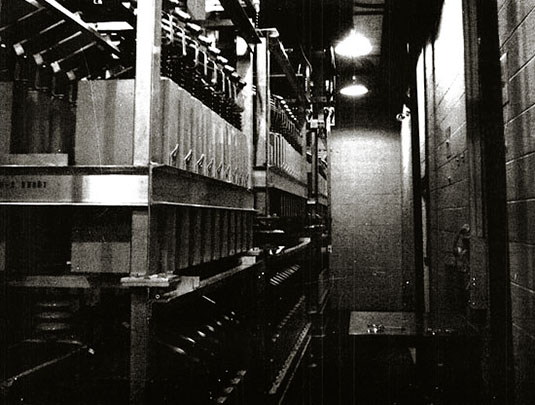

The Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex in Cavalier County, North Dakota, is the focus of an amazing set of images hosted by the U.S. Library of Congress, showing this squat and evocative megastructure in various states of construction and completion.

It’s a huge pyramid in the middle of nowhere tracking the end of the world on radar, an abstract geometric shape beneath the sky without a human being in sight, or it could even be the opening scene of an apocalyptic science fiction film—but it’s just the U.S. military going about its business, building vast and other-worldly architectural structures that the civilian world only rarely sees.

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

As Pruned described these structures back in 2008, it was a “mastaba-shaped radar facility reminiscent of the work of architect Étienne-Louis Boullée.”

As such, Pruned suggests, it offers convincing architectural evidence that we should consider “the “U.S. anti-ballistic landscape as a subset of Land Art”—as lonely pieces of abandoned infrastructure isolated amidst sublime and almost unreachably remote locations.

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

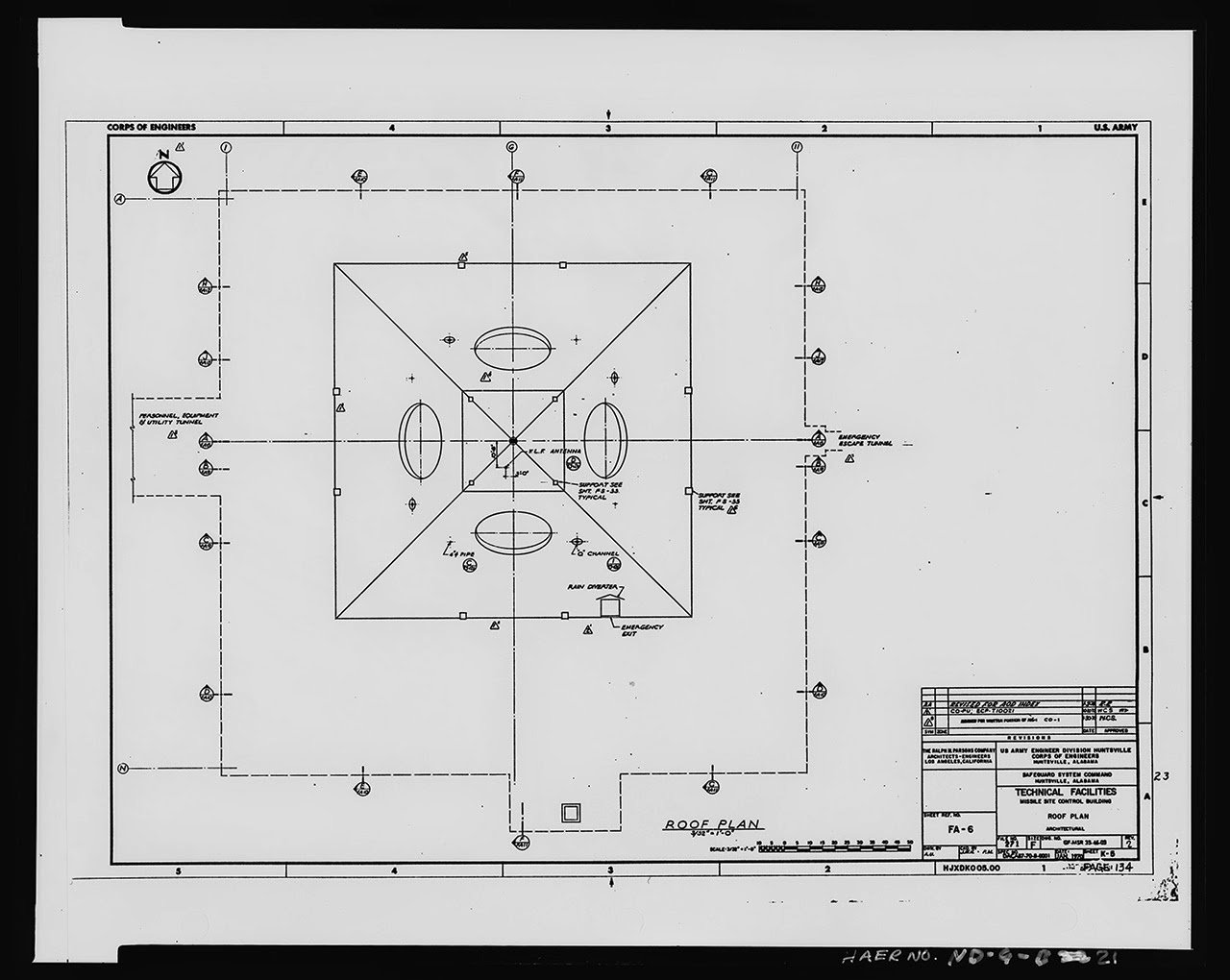

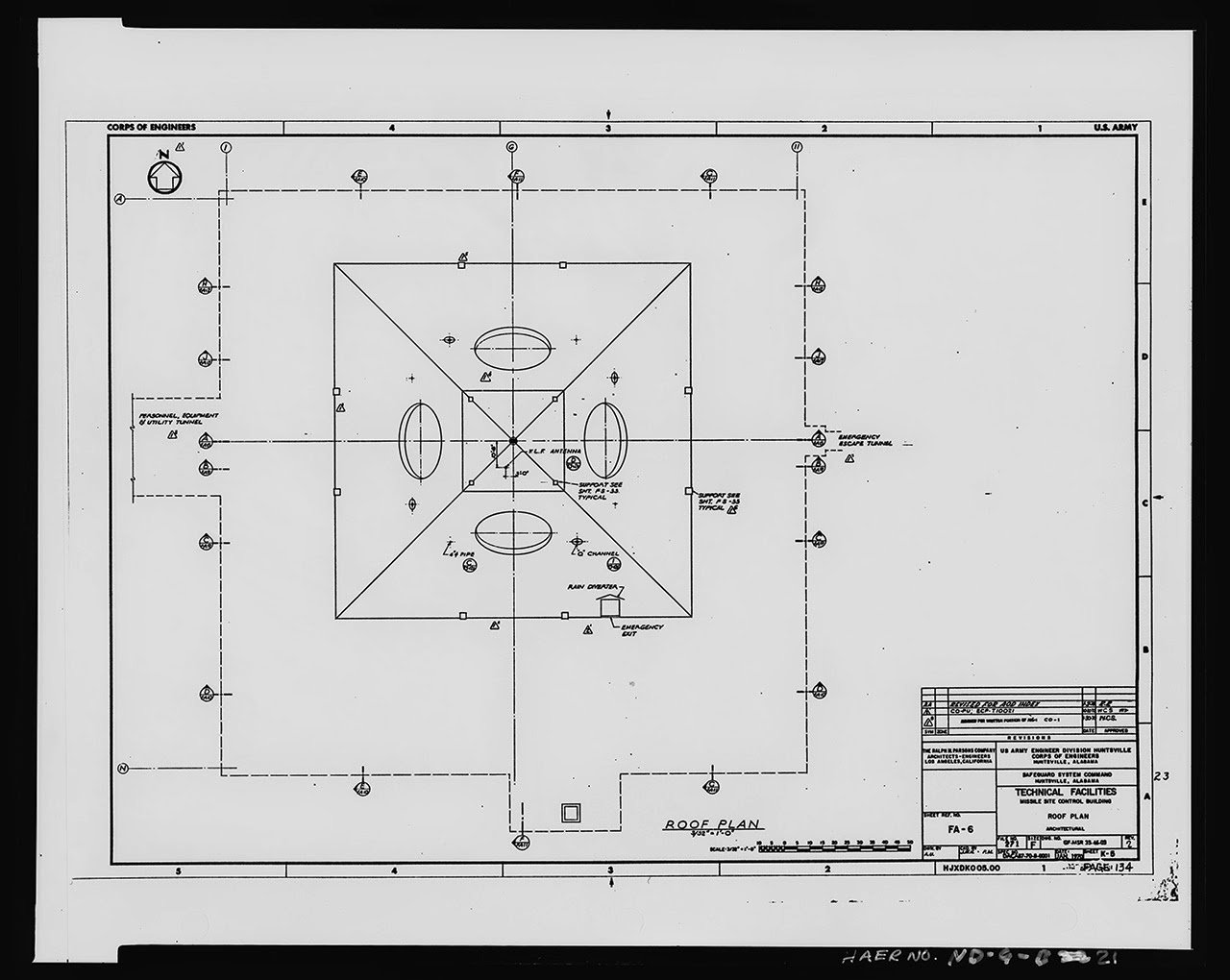

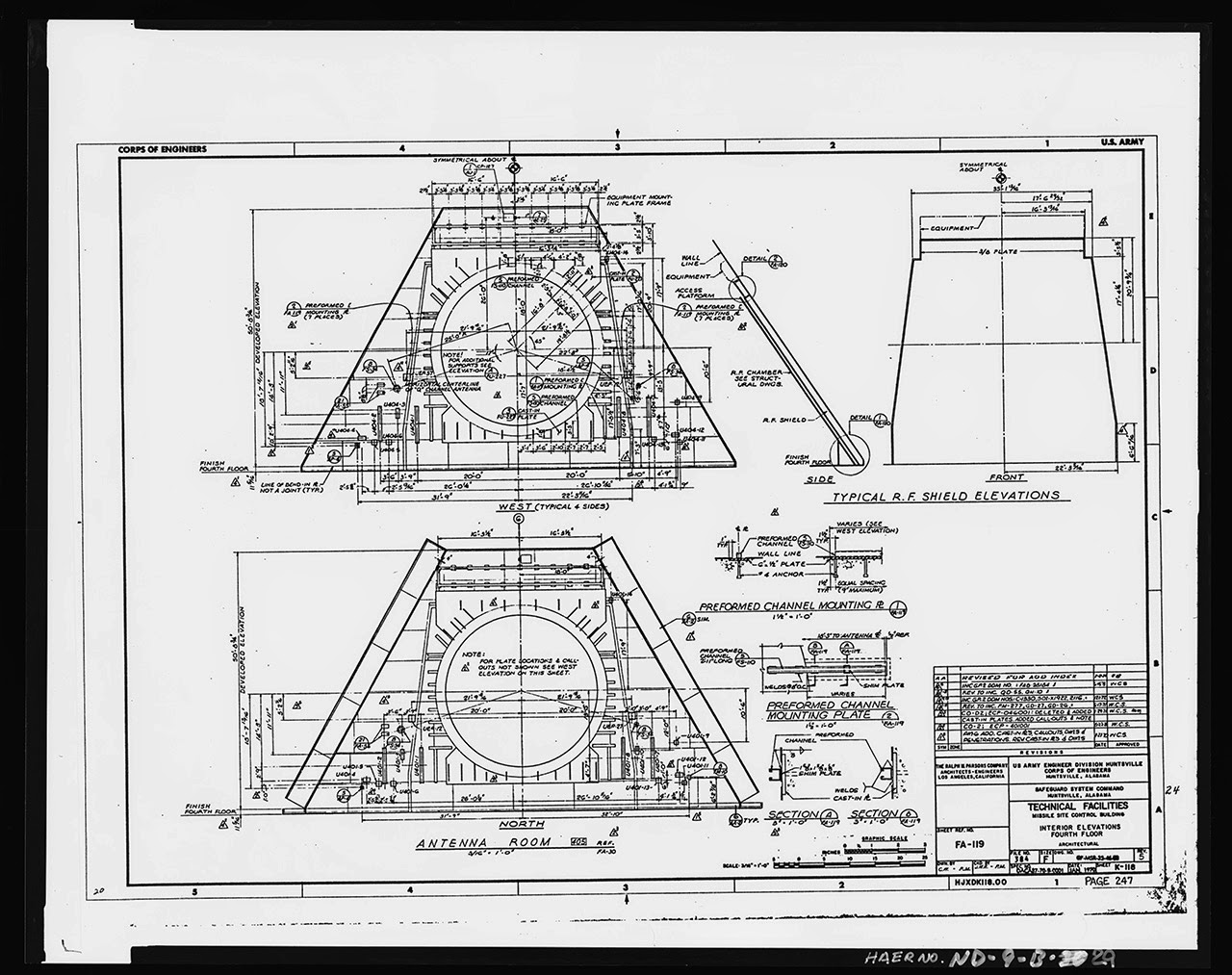

The photos seen here, taken for the U.S. government by photographer Benjamin Halpern, show the central pyramid—pyramid, monument, modular obelisk: whatever you want to call it—that served as the site’s missile-tracking station. Its omnidirectional all-seeing white circles stared endlessly at invisible airborne objects moving beyond the horizon.

The Library of Congress gives the pyramid’s location somewhat absurdly as “Northeast of Tactical Road; southeast of Tactical Road South.” In other words, it’s ensconced somewhere in a maze of self-reference and tautology, perhaps deliberately obscuring exactly how you’re meant to arrive at this place.

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

Yet the pyramid has become something of a roadtripper’s delight in the last decade or two. When I initially published a slightly different version of this post on Gizmodo, commenters from around the world jumped in with their own photos and memories of driving hours out of their way to find these military ruins looming spookily on the horizon.

Most if not all of them then discovered that it was as easy as simply saying hello to the guard, walking unencumbered through the front gate, and then hanging out for hours, running up the side of the pyramid, taking pictures against the North Dakota sky, and enjoying this American Giza as a peculiarly avant-garde site for an afternoon picnic.

You can even see the structures, arranged like some ritual sequence of spatial objects—a chapel of radar aligned with war—on Google Street View.

[Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via Google Street View].

[Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via Google Street View].

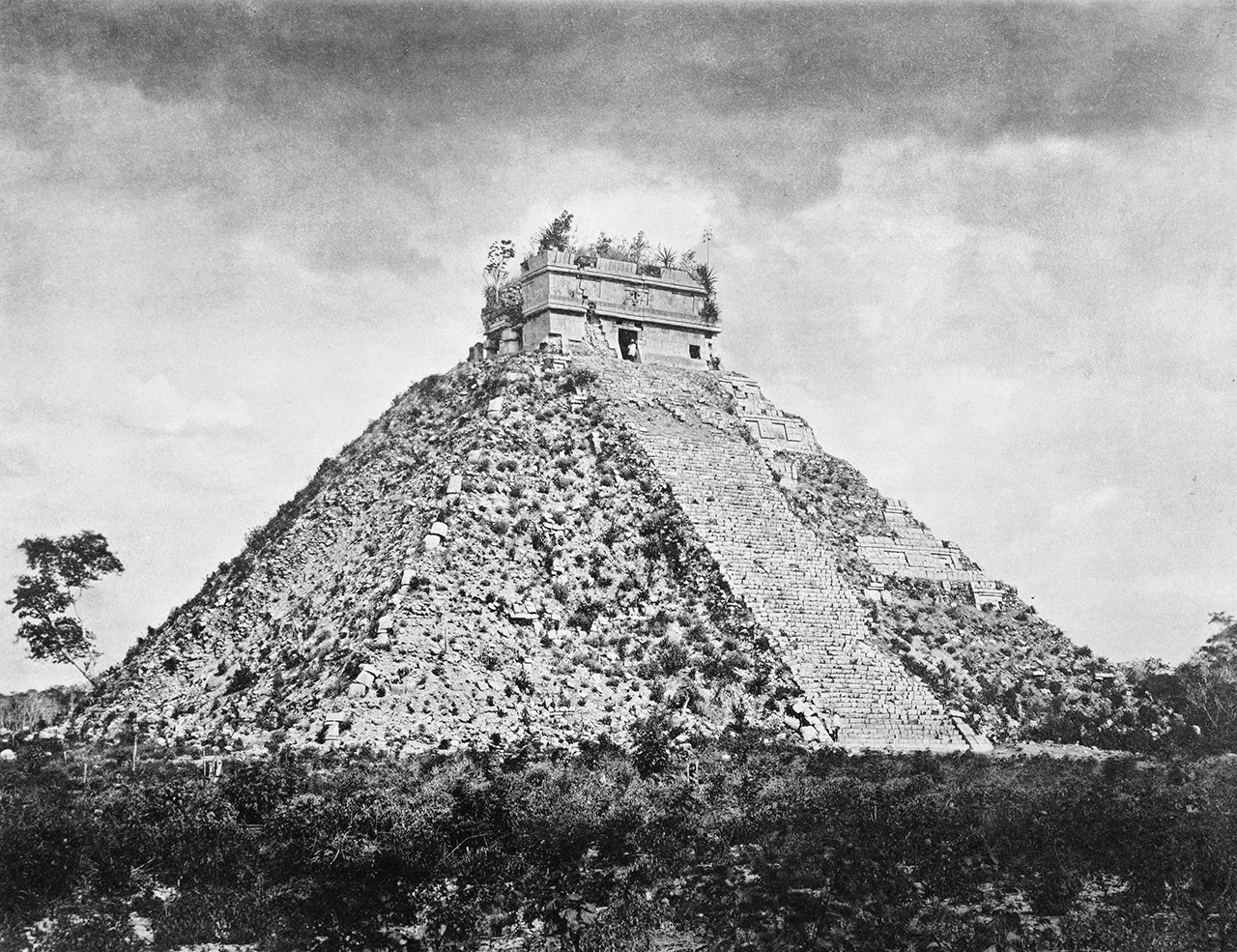

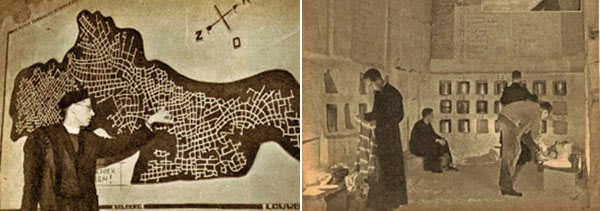

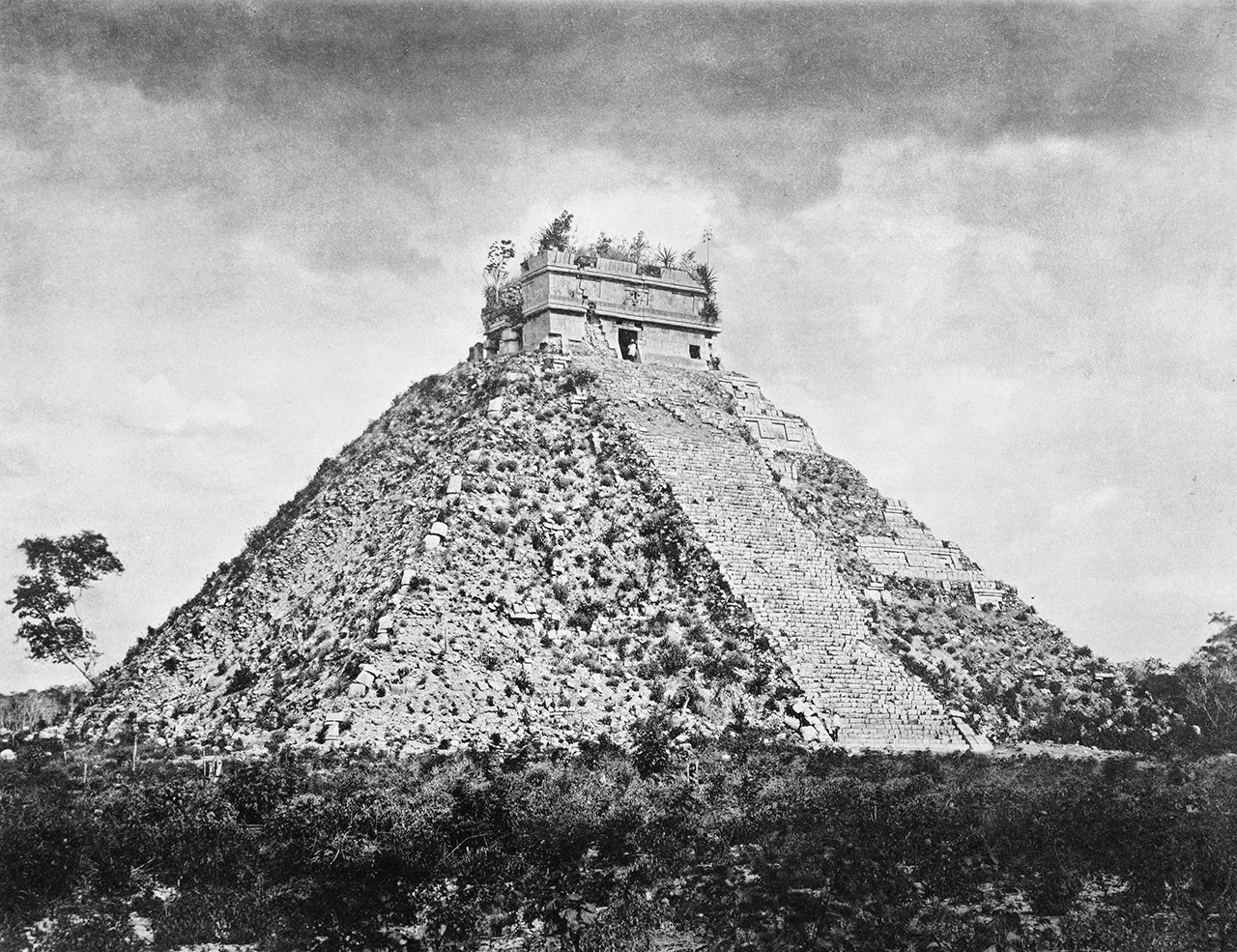

One thing I like so much about these shots is how they resemble early expeditionary photos of the hulking Mayan ruins found at Chichén Itzá.

Check out these comparative shots, for example, where the latter image was taken by photographer Henry Sweet during a 19th-century archaeological journey led by Alfred P. Maudslay. The photo was featured as part of an exhibition at the University of North Carolina back in 2007.

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress; (bottom) photo by Henry Sweet, courtesy of the UNC-Chapel Hill].

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress; (bottom) photo by Henry Sweet, courtesy of the UNC-Chapel Hill].

Of course, there is nothing really to compare outside of their same overall geometry—yet it’s striking to consider the functional, if obviously metaphoric, similarities here as well.

One structure was built as part of a kind of analogue system for tracking divine events and celestial calendars, as dark constellations of gods spun across the sky; the other was a temple to mathematics built for guiding and pinging missiles as they streaked horizon to horizon, a site of early warning against the apocalypse, as a new zodiac of nuclear warheads would burst open to shine their world-blinding light on the obliterated landscapes below.

Trajectories, paths, horizons: both pyramids, in a sense, were architectural monuments for navigation of different kinds. Both timeless, strange, and seemingly inhuman: spatial artifacts of lost civilizations.

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

In any case, the original photos on the Library of Congress website are heavily specked with dust and some lens artifacts, but I’ve cleaned up my favorites and posted some of them here.

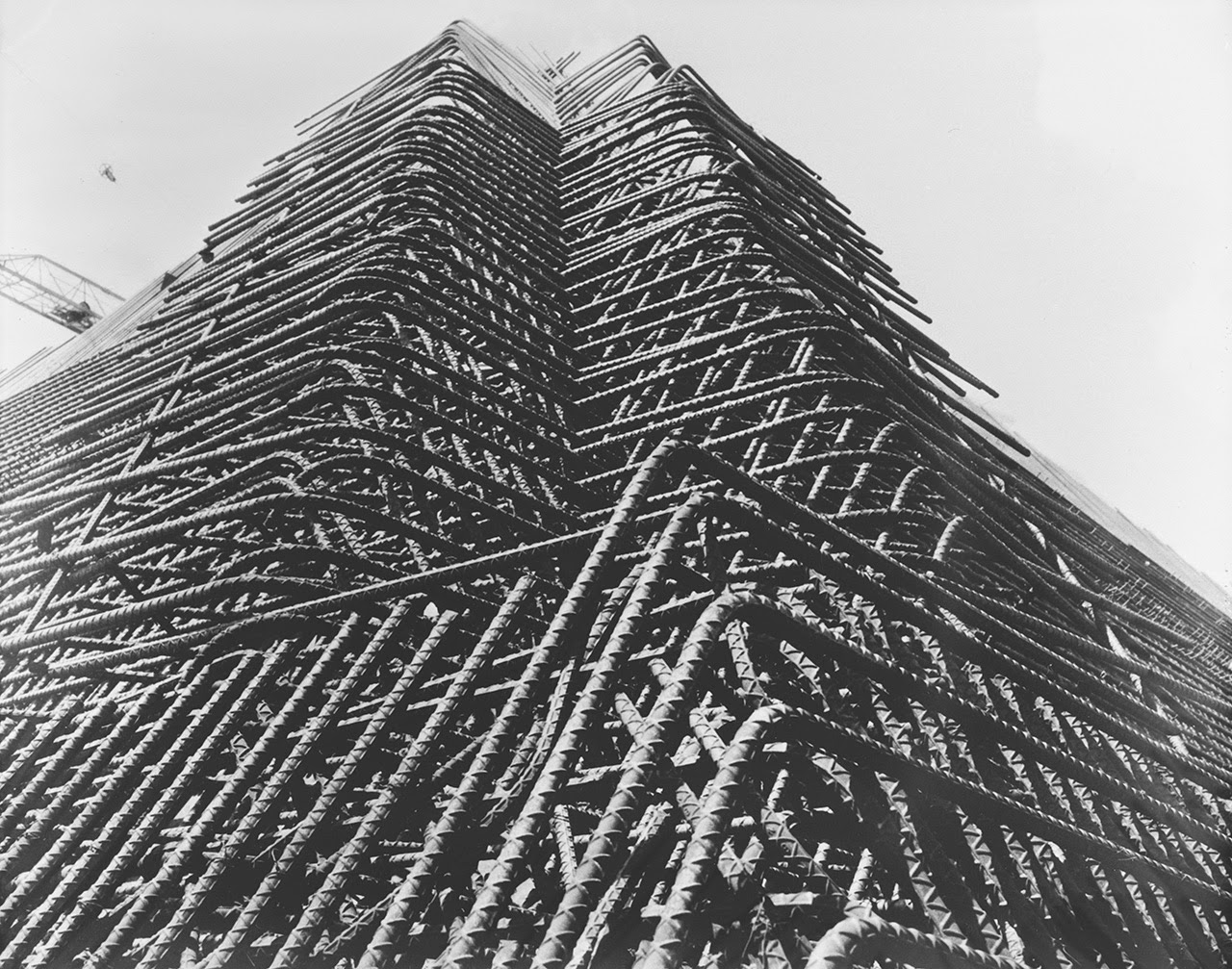

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

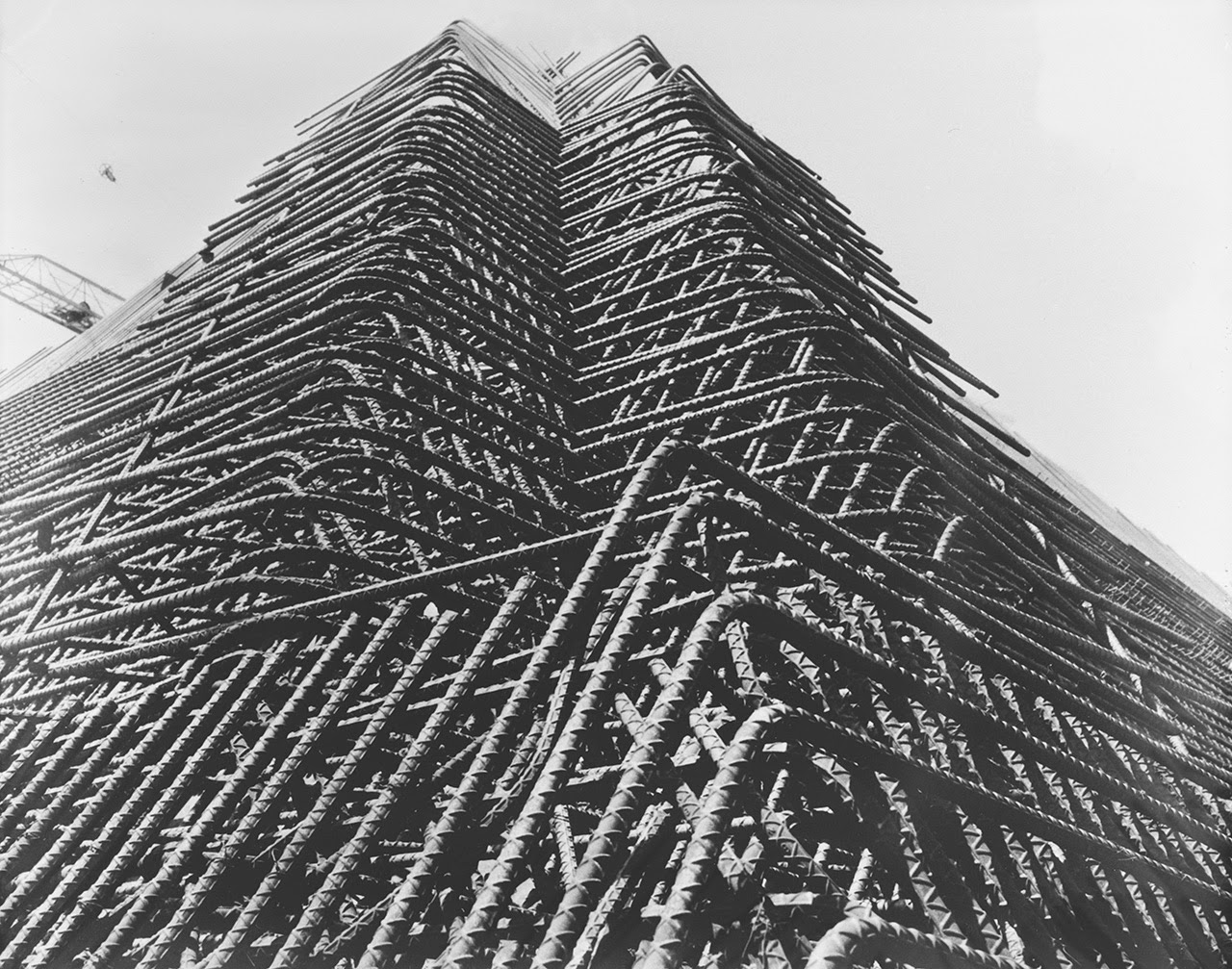

This is how modern-day pyramids are made: huge budgets and ziggurats of rebar, as tiny figures wearing hardhats scramble around amidst gargantuan geometric forms, checking diagrams against reality and trying not to think of the nuclear war this structure was being built to track.

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress].

(An earlier version of this post previously appeared on Gizmodo).

[Images: Via Borderland Sciences].

[Images: Via Borderland Sciences]. [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The antenna field at Jim Creek, via

[Image: The antenna field at Jim Creek, via  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: An entrance to the quarry in Kanne; photo by

[Image: An entrance to the quarry in Kanne; photo by  [Images: Monks underground; via

[Images: Monks underground; via  The “streets” were named, but not always easy to follow; however, this didn’t stop officers stationed there from occasionally going out to explore the older tunnels at night. A former employee named Bob Hankinson describes how he used to navigate:

The “streets” were named, but not always easy to follow; however, this didn’t stop officers stationed there from occasionally going out to explore the older tunnels at night. A former employee named Bob Hankinson describes how he used to navigate:  [Image: An entrance into the NATO complex;

[Image: An entrance into the NATO complex;

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via

[Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via  [Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)]. [Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].