[Image: From Die Hard, directed by John McTiernan based on the novel Nothing Lasts Forever by Roderick Thorpe].

[Image: From Die Hard, directed by John McTiernan based on the novel Nothing Lasts Forever by Roderick Thorpe].

While watching Die Hard the other night—easily one of the best architectural films of the past 25 years—I kept thinking about an essay called “Lethal Theory” by Eyal Weizman—itself one of the best and most consequential architectural texts of the past decade (download the complete PDF).

In it, Weizman—an Israeli architect and prominent critic of that nation’s territorial policy—documents many of the emerging spatial techniques used by the Israeli Defense Forces in their high-tech, legally dubious 2002 invasion of Nablus. During that battle, Weizman writes, “soldiers moved within the city across hundred-meter-long ‘overground-tunnels’ carved through a dense and contiguous urban fabric.” Their movements were thus almost entirely camouflaged, with troop movements hidden from above by virtue of always remaining inside buildings. “Although several thousand soldiers and several hundred Palestinian guerrilla fighters were maneuvering simultaneously in the city,” Weizman adds, “they were so ‘saturated’ within its fabric that very few would have been visible from an aerial perspective at any given moment.”

Worthy of particular emphasis is Weizman’s reference to a technique called “walking through walls”:

Furthermore, soldiers used none of the streets, roads, alleys, or courtyards that constitute the syntax of the city, and none of the external doors, internal stairwells, and windows that constitute the order of buildings, but rather moved horizontally through party walls, and vertically through holes blasted in ceilings and floors.

Weizman goes on to interview a commander of the Israeli Paratrooper Brigade. The commander describes his forces as acting “like a worm that eats its way forward, emerging at points and then disappearing. We were thus moving from the interior of homes to their exterior in a surprising manner and in places we were not expected, arriving from behind and hitting the enemy that awaited us behind a corner.”

This is how the troops could “adjust the relevant urban space to our needs,” he explains, and not the other way around.

Indeed, the commander thus exhorted his troops as follows: “There is no other way of moving! If until now you were used to moving along roads and sidewalks, forget it! From now on we all walk through walls!”

[Image: Israeli troops scan walls in a refugee camp; photo by Nir Kafri (2003), from Eyal Weizman’s essay “Lethal Theory”].

[Image: Israeli troops scan walls in a refugee camp; photo by Nir Kafri (2003), from Eyal Weizman’s essay “Lethal Theory”].

Weizman illustrates the other side of this terrifyingly dislocating experience by quoting an article originally published during the 2002 invasion. Here, a Palestinian woman, whose home was raided, recounts her witnessing of this technique:

Imagine it—you’re sitting in your living room, which you know so well; this is the room where the family watches television together after the evening meal. . . . And, suddenly, that wall disappears with a deafening roar, the room fills with dust and debris, and through the wall pours one soldier after the other, screaming orders. You have no idea if they’re after you, if they’ve come to take over your home, or if your house just lies on their route to somewhere else. The children are screaming, panicking. . . . Is it possible to even begin to imagine the horror experienced by a five-year-old child as four, six, eight, twelve soldiers, their faces painted black, submachine guns pointed everywhere, antennas protruding from their backpacks, making them look like giant alien bugs, blast their way through that wall?

In fact, I’m reminded of a scene toward the end of the recent WWII film Days of Glory in which we see a German soldier blasting his way horizontally through a house, wall by wall, using his bazooka as a blunt instrument of architectural reorganization—“adjusting the relevant space to his needs,” we might say—and chasing down the French troops without limiting himself to doors or stairways.

In any case, post-battle surveys later revealed that “more than half of the buildings in the old city center of Nablus had routes forced through them, resulting in anywhere from one to eight openings in their walls, floors, or ceilings, which created several haphazard crossroutes”—a heavily armed improvisational navigation of the city.

So why do I mention all this in the context of Die Hard? The majority of that film’s interest, I’d suggest, comes precisely through its depiction of architectural space: John McClane, a New York cop on his Christmas vacation, moves through a Los Angeles high-rise in basically every conceivable way but passing through its doors and hallways.

[Images: From Die Hard].

[Images: From Die Hard].

McClane explores the tower—called Nakatomi Plaza—via elevator shafts and air ducts, crashing through windows from the outside-in and shooting open the locks of rooftop doorways. If there is not a corridor, he makes one; if there is not an opening, there will be soon.

[Images: From Die Hard].

[Images: From Die Hard].

Over the course of the film, McClane blows up whole sections of the building; he stops elevators between floors; and he otherwise explores the internal spaces of Nakatomi Plaza in acts of virtuoso navigation that were neither imagined nor physically planned for by the architects.

His is an infrastructure of nearly uninhibited movement within the material structure of the building.

The film could perhaps have been subtitled “lessons in the inappropriate use of architecture,” were that not deliberately pretentious. But even the SWAT team members who unsuccessfully raid the structure come at it along indirect routes, marching through the landscaped rose garden on the building’s perimeter, and the terrorists who seize control of Nakatomi Plaza in the first place do so after arriving through the service entrance of an underground car park.

[Images: From Die Hard].

[Images: From Die Hard].

What I find so interesting about Die Hard—in addition to unironically enjoying the film—is that it cinematically depicts what it means to bend space to your own particular navigational needs. This mutational exploration of architecture even supplies the building’s narrative premise: the terrorists are there for no other reason than to drill through and rob the Nakatomi Corporation’s electromagnetically sealed vault.

Die Hard asks naive but powerful questions: If you have to get from A to B—that is, from the 31st floor to the lobby, or from the 26th floor to the roof—why not blast, carve, shoot, lockpick, and climb your way there, hitchhiking rides atop elevator cars and meandering through the labyrinthine, previously unexposed back-corridors of the built environment?

Why not personally infest the spaces around you?

[Images: From Die Hard].

[Images: From Die Hard].

I might even suggest that what would have made Die Hard 2 an interesting sequel—sadly, the series is unremarkable for the fact that each film is substantially worse than the one before—would have been if Die Hard’s spatial premise had been repeated on a much larger urban scale.

For example, Weizman outlines what the Israeli Defense Forces call “hot pursuit”—that is, to “break into Palestinian controlled areas, enter neighborhoods and homes in search of suspects, and take suspects into custody for purposes of interrogation and detention.” This becomes a spatially extraordinary proposition when you consider that someone could be kidnapped from the 4th floor of a building by troops who have blasted through the walls and ceilings, coming down into that space from the 5th floor of a neighboring complex—and that the abductors might only have made it that far in the first place after moving through the walls of other structures nearby, blasting upward through underground infrastructure, leaping terrace-to-terrace between buildings, and more.

An alternative-history plot for a much better Die Hard 2 could thus perhaps include a scene in which the rescuing squad of John McClane-led police officers does not even know what building they are in, a suitably bewildering encapsulation of this method of moving undetected through the city.

“Walking through walls” thus becomes a kind of militarized parkour.

[Image: Inside Nakatomi space, from Die Hard].

[Image: Inside Nakatomi space, from Die Hard].

Indeed, recent films like The Bourne Ultimatum, Casino Royale, District 13, and many others could be viewed precisely as the urban-scale realization of Die Hard’s architectural scenario. Even The Bank Job—indeed, any bank heist film at all involving tunnels—makes this Weizmanian approach to city space quite explicit.

[Image: From Die Hard; it’s hard to see here, but an LAPD SWAT team is raiding the Nakatomi Building by way of lateral movements across the surrounding landscape].

[Image: From Die Hard; it’s hard to see here, but an LAPD SWAT team is raiding the Nakatomi Building by way of lateral movements across the surrounding landscape].

Tangentially, I’m reminded of Matt Jones’s thought-provoking 2008 blog post about the urban differences between the Jason Bourne and James Bond film franchises. Jones writes that “there’s no travel in the new Bond”; there are simply “establishing shots of exotic destinations.” By the end of a Bond film, he adds, you simply “feel like you are in the international late-capitalist nonplace,” a geography with neither landmarks nor personal memory.

Compare the paradoxically unmoving, amnesiac geography of James Bond, then, to the compressed spaces of Paul Greengrass-directed Jason Bourne films. These films are “set in Schengen,” Jones writes, “a connected, border-less Mitteleurope that can be hacked and accessed and traversed—not without effort, but with determination, stolen vehicles and the right train timetables.” Indeed, Jones memorably suggests, “Bourne wraps cities, autobahns, ferries and train terminuses around him as the ultimate body-armor.”

Rather than Bond’s private infrastructure [of] expensive cars and toys, Bourne uses public infrastructure as a superpower. A battered watch and an accurate U-Bahn time-table are all he needs for a perfectly-timed, death-defying evasion of the authorities.

The space of the city is used in profoundly different ways by Bond and Bourne—but to this duality I would add John McClane of the original Die Hard.

If Jason Bourne’s actions make visible the infrastructure-rich, borderless world of the EU, then John McClane shows us a new type of architectural space altogether—one that we might call, channeling topology, Nakatomi space, wherein buildings reveal near-infinite interiors, capable of being traversed through all manner of non-architectural means. In all three cases—with Bond, Bourne, and McClane—it is Hollywood action films that reveal to us something very important about how cities can be known, used, and navigated: these films are filled with the improvisational crossroutes that constitute Eyal Weizman’s “Lethal Theory.”

As I wrote the other day, crime is a way to use the city.

[Image: From Die Hard].

[Image: From Die Hard].

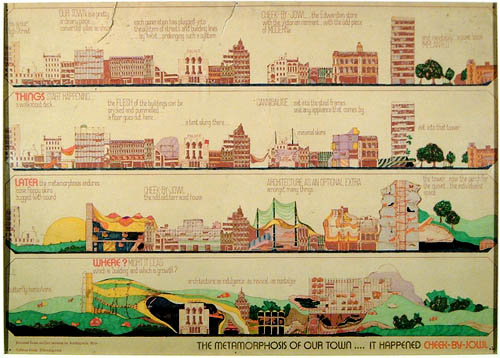

On the other hand, as Weizman points out, this is not a new approach to built space at all:

In fact, although celebrated now as radically new, many of the procedures and processes described above have been part and parcel of urban operations throughout history. The defenders of the Paris Commune, much like those of the Kasbah of Algiers, Hue, Beirut, Jenin, and Nablus, navigated the city in small, loosely coordinated groups moving through openings and connections between homes, basements, and courtyards using alternative routes, secret passageways, and trapdoors.

This is all just part of “a ghostlike military fantasy world of boundless fluidity, in which the space of the city becomes as navigable as an ocean.”

[Image: From Die Hard].

[Image: From Die Hard].

Treated as an architectural premise, Die Hard becomes an exhilarating catalog of unorthodox movements through space. I would suggest again, then, that where the various Die Hard sequels went wrong was in abandoning this spatial investigation—one that could very easily have been scaled-up to encompass a city—and following, instead, the life of one character: John McClane. But, when taken out of Nakatomi Plaza—that is, out of the boundless, oceanic fluidity of Nakatomi space—McClane is reduced to an action film cliché whose failing charisma no amount of wise-cracking can salvage.

(I remembered while writing this post that I actually discussed Die Hard on National Public Radio last year; you can listen to that show here).

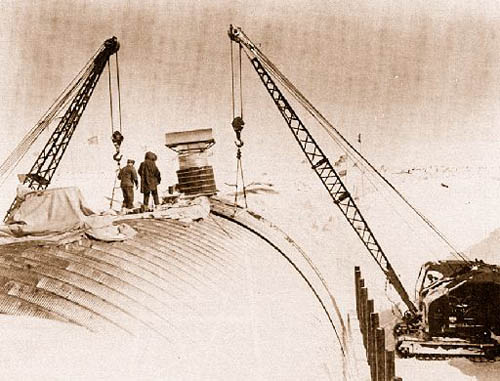

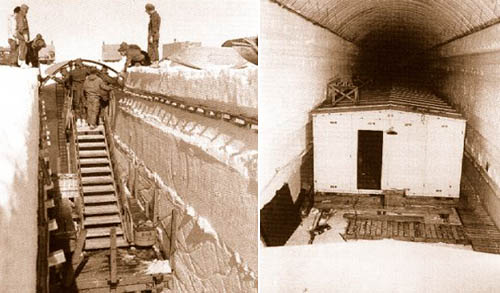

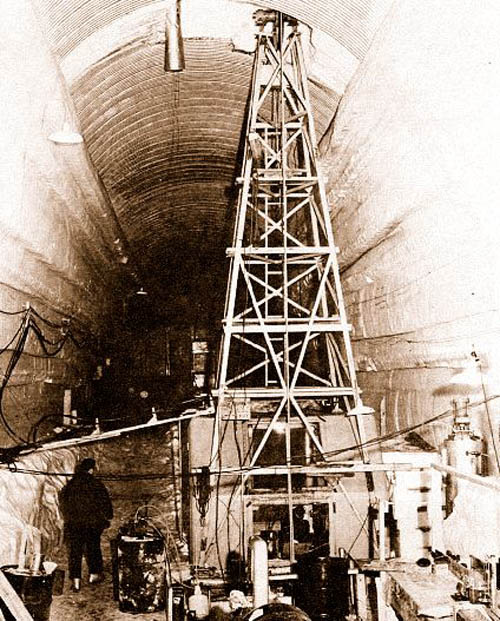

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz].

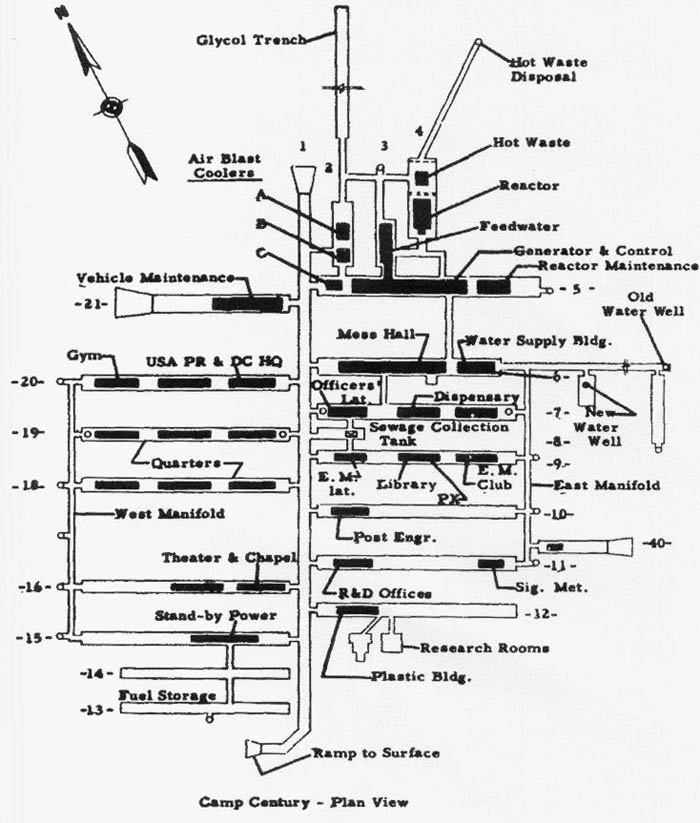

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via Frank J. Leskovitz]. [Image: The plan of Camp Century; via Frank J. Leskovitz].

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via Frank J. Leskovitz].  [Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the American Geophysical Union].

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the American Geophysical Union].

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

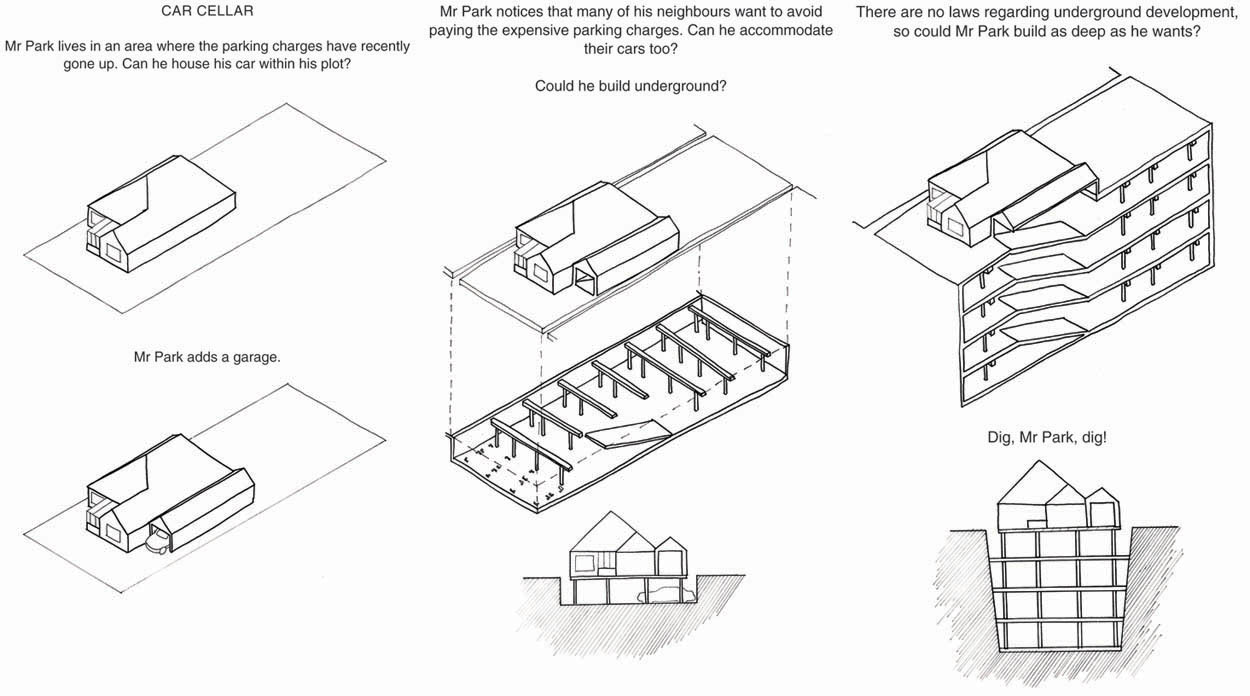

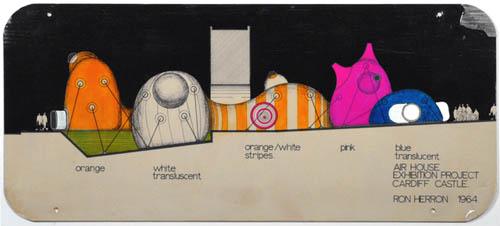

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of  [Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

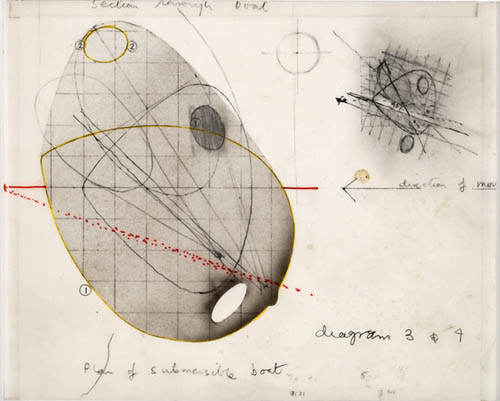

[Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of  [Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal

[Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal  [Image: “Proposal for a

[Image: “Proposal for a  [Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a

[Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a  [Image: Proposal “

[Image: Proposal “ [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Israeli troops scan walls in a refugee camp; photo by Nir Kafri (2003), from Eyal Weizman’s essay “Lethal Theory”].

[Image: Israeli troops scan walls in a refugee camp; photo by Nir Kafri (2003), from Eyal Weizman’s essay “Lethal Theory”].

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Inside Nakatomi space, from

[Image: Inside Nakatomi space, from  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: An etching by

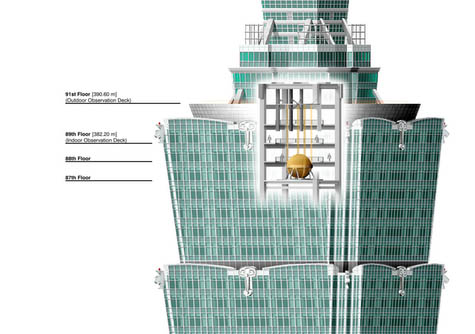

[Image: An etching by  [Image: Diagram of Taipei 101’s earthquake ball via the

[Image: Diagram of Taipei 101’s earthquake ball via the  [Image: The 728-ton damper in Taipei 101, photographed by

[Image: The 728-ton damper in Taipei 101, photographed by  [Image: Animated GIF via

[Image: Animated GIF via