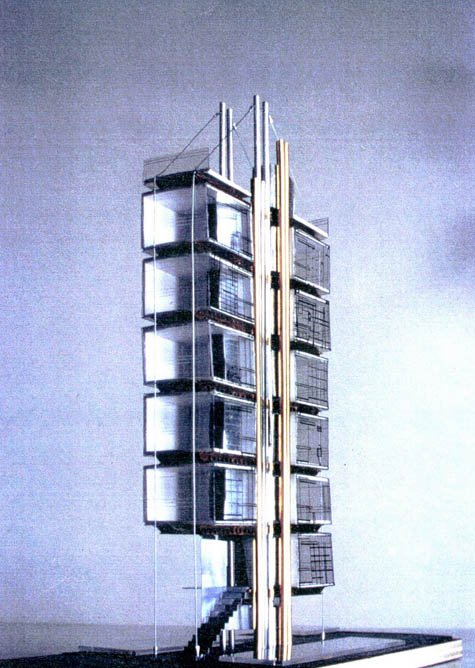

[Image: The Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello; modular additions can be seen bolted on from below. Read the project PDF].

[Image: The Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello; modular additions can be seen bolted on from below. Read the project PDF].

Combining Rails to Trails, William Gibson’s Virtual Light, and the same repurposed-preservation strategies behind New York’s High Line, Bay Area architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello have called for stabilizing the disused – and soon to be entirely dismantled – portion of the Bay Bridge. They would then turn it into a pedestrianized urban park and outdoor sports attraction.

[Image: The Bay Bridge and its replacement; on the right is the piece that Rael San Fratello would like to see stabilized. Image via Wikipedia].

[Image: The Bay Bridge and its replacement; on the right is the piece that Rael San Fratello would like to see stabilized. Image via Wikipedia].

And if it works for the Bay Bridge, they suggest, it could work for other disused bridges elsewhere.

“This proposal seeks to repurpose abandoned and closed bridges as sites of potential for parks, cultural centers and housing,” the architects write in the project’s accompanying PDF. In the process, they hope “to demonstrate the potential for re-purposing historic American bridge infrastructure as possible sites for sustainable urban housing and linear parks.”

The immense load capacity of rail bridges allows for the support of program beyond that of parks, suggesting the urbanization of bridges. While the current economic climate suggests a surplus of housing, the economic reality also suggests a push towards urbanization and often the “affordable” housing constructed in suburban environments, which encroaches on the rural, is not what is needed. Instead, by using abandoned bridges in urban areas, we are creating opportunities for sustainable low-cost housing within the urban realm—creating the potential for creative speculation among housing developers by expounding upon the nascent potential of a layered housing-park-bridge typology.

While, on one level, this simply side-steps the immense financial implications associated with structurally maintaining these bridges, and, on another level, it bears an unfortunate resemblance to Boris Johnson’s recent – if not necessarily well-received – call for an inhabitable bridge across the Thames, it does also kick-start a conversation about what we might be able to do with the massive pieces of civic infrastructure that dot the U.S. and are currently scheduled for replacement and demolition.

[Images: (top) Tennis court, bicycle path, and observation module; (middle) Outdoor auditorium; (bottom) swimming pool on the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

[Images: (top) Tennis court, bicycle path, and observation module; (middle) Outdoor auditorium; (bottom) swimming pool on the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

And, I have to admit, it would simply be cool:

Imagine housing, recreational and cultural facilities connected to a continuous, lushly planted, green strip, floating above the water—an aerial garden, as the city’s newest park through which you could walk and wander and enjoy the most spectacular views of the bay.

Of course, critics like James Howard Kunstler might suggest that reusing rail infrastructure – or, in this case, highway infrastructure – as anything other than a rejuvenated national rail service is “decadence at its purest,” it is surely just as decadent to watch as functional pieces of infrastructure rot on all sides, as you sit there with your arms crossed, waiting for the nation’s taxpayers to agree with your views on reuse.

[Images: Other habitable bridge: (top) Florence’s Ponte Vecchio; (second) a painting by Peter Jackson of “Old London Bridge“; (third and bottom) Constant’s New Babylon].

[Images: Other habitable bridge: (top) Florence’s Ponte Vecchio; (second) a painting by Peter Jackson of “Old London Bridge“; (third and bottom) Constant’s New Babylon].

In any case, as someone who literally never enjoyed driving across the Bay Bridge for seismic-safety reasons, I have to point out that this proposal still comes with its own set of earthquake-related issues. I was interested, however, to read in the Economist just this week that “there are few safe places to ride out an earthquake. Surprisingly, though, a recently constructed bridge is often one of them.”

Engineers have become good at designing bridges that are earthquake-resistant enough to preserve the lives of those caught crossing when a quake strikes. The problem is that the bridge is often unusable afterwards.

Nonetheless, if you had put millions of dollars’ worth of landscape and housing onto a bridge that was then left abandoned and “unusable” after an earthquake, it would be a very foolhardy investment, indeed.

[Image: Final render of the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

[Image: Final render of the Bay Line by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello].

But what of bridges in non-seismic zones? In Sydney, for instance, due to the peninsular nature of walks along Cremorne Point and through Kirribilli, there are places where the Sydney Harbor Bridge appears not to be crossing over water at all, but standing over the rooftops of the city, anchored into the neighborhood. It looks more like a new kind of inland megastructure, strung above the streets and restaurants, like something designed by Perdido Street Station-era China Miéville, than a harbor bridge. An industrial cathedral of exposed ribs and steel tension lines, arcing up into the skyline.

So what if you hung houses from it? What amazing typologies of bolt-on architectural prosthetics could we create, if bridges were aerial foundations and they carried not cars or locomotives but schools and piazzas?

In fact, I’m reminded of this unexpectedly inspiring – structurally speaking – proposal by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which sought to string the suspension cables of a new pedestrian bridge from inside the nearby buildings of a rebuilt Leamouth Peninsula (click through to their image gallery for more).

[Image: A proposal for London’s Leamouth Peninsula by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill].

[Image: A proposal for London’s Leamouth Peninsula by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill].

Returning to Rael San Fratello‘s Bay Line, though, there are obviously still huge issues associated with the unusually catastrophic nature of structural failure when it comes to inhabitable bridges, as well as the financially prohibitive needs of regular maintenance, but treating suspension bridges simply as another type of district in the city is an undeniably interesting urban idea.

(Via Streetsblog SF and Ronald Rael. Meanwhile, Rael’s recently published book Earth Architecture is an excellent and thoughtful survey of earthen structures across the world and throughout building history; Rael’s old school blog, megablog, is also worth a read for its eye-popping and often literally world-altering architectural ambitions).

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: Screen grabs from James Cameron’s Aliens].

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: Preflooded Wetlands by Liam Young and Darryl Chen].

[Image: Preflooded Wetlands by Liam Young and Darryl Chen].

[Image: Waste and Biogas and Permacultural Hinterland by Liam Young and Darryl Chen].

[Image: Waste and Biogas and Permacultural Hinterland by Liam Young and Darryl Chen]. [Image: Primordial Garden Sanctuary and Incarceration Tower by Liam Young and Darryl Chen].

[Image: Primordial Garden Sanctuary and Incarceration Tower by Liam Young and Darryl Chen]. [Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of

[Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of  [Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of

[Image: The Maunsell Sea Forts, photographed by Pete Speller, courtesy of

[Images: Inside the forts; photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of

[Images: Inside the forts; photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of

[Images: Photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of

[Images: Photos by Pete Speller, courtesy of  [Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the

[Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the  [Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of

[Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw]. [Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn].

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn]. [Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the

[Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the  [Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain

[Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel].

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel]. [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Parentheses, an “habiter dans les interstices de la ville,” by Catherine Rannou].

[Image: Parentheses, an “habiter dans les interstices de la ville,” by Catherine Rannou]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: A project by

[Image: A project by  [Image: A project by

[Image: A project by  [Image: A project by

[Image: A project by  [Image: The diagram of architectural outlines that was laser-cut into the book’s pages, recreating the illusory volume of a cinematic space].

[Image: The diagram of architectural outlines that was laser-cut into the book’s pages, recreating the illusory volume of a cinematic space]. [Image: A project by

[Image: A project by

[Images: Another project by

[Images: Another project by

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: The offshore metropolis of Oil Rocks, Azerbaijan, via

[Image: The offshore metropolis of Oil Rocks, Azerbaijan, via  [Image: The Oil Rocks postage stamp, via

[Image: The Oil Rocks postage stamp, via  [Image: Other artificial peninsular cities of Baku, seen from above.

[Image: Other artificial peninsular cities of Baku, seen from above.  [Images: Photos of offshore oil structures in the Caspian by

[Images: Photos of offshore oil structures in the Caspian by