[Image: A bubbling tar seep near Wilshire Boulevard].

[Image: A bubbling tar seep near Wilshire Boulevard].

We’re in the final few days of the Landscape Futures Super-Workshop now, heading out soon for another field trip this afternoon, after half a week of presentations, lectures, site visits, crits, walks, and much else besides.

By way of a rapid and by no means thorough update, I figured I’d give a rundown of some of the many, many things we’ve done so far, having hit the ground running on Tuesday morning with a tour through old oil sites to see the surface indications of L.A.’s subterranean petrology. We visited pumping stations, tar pits, and camouflaged drilling rigs, discussing explosive clouds of methane gas and the machines that monitor those invisible but toxic accumulations, and trying to understand the financial industries that have arisen to package and sell fossil fuels from windowless offices in Los Angeles, all during a series of drives led by architect and local oil-history expert Ben Loescher.

[Images: Skulls and bones at the La Brea Tar Pits].

[Images: Skulls and bones at the La Brea Tar Pits].

We heard from students from the Bartlett, Columbia, and the Arid Lands Institute, seeing proposals for urban-scale fortresses made from freshwater injection wells, artificial troglodyte homesteads in Long Beach constructed with from rocks harvested from San Gabriel debris basins, crawling bagpipe-machines (actually built!) that walked around London powered by bike pumps and bleating like sheep, pollution-harvesting devices in the skies of southern California that will collect dust and carbon through electromagnetic attractors, future climate-prediction mechanisms and the networked sensorscapes that make them possible, synthetic orchards, mobile well heads, resistance-powered lamps in the chaparral monitoring seasonal windspeeds, “kit architectures” for unstable landscapes, “cloud dispensers” and other augmented climatologies, machine-cowboys overseeing herds of hydrotropic robots on the dry bed of Owens Lake, groundwater filtration interfaces for sites where the hills hit urban flatlands, open-source bio-fuel experimentation labs run by amateur genetic engineers, urban oxygen gardens, experimental greenhouses running test-climates for a future earth, and a dozen other projects, all of which will continue to be developed, tweaked, or abandoned as the workshop moves on.

[Image: A “satellite tracking station” near the headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Image: A “satellite tracking station” near the headwaters of the L.A. River].

We’ve discussed cinema, time, repetition, noise, and landscape through the interpretive lens of Ed Keller, who introduced us to “the multiple, the nonlinear, [and] the demonic” as represented through non-narrative jumpcuts and other strange edits of logic and sense. We traced infrastructural maps of L.A.’s water supply with the Arid Lands Institute.

[Image: Learning about water infrastructure courtesy of the Arid Lands Institute].

[Image: Learning about water infrastructure courtesy of the Arid Lands Institute].

And then we headed out on a cloudless Wednesday morning, in a five-car caravan from our hotel in Venice, to visit the headwaters of the L.A. River, photographing wake-engineering fins made of concrete and looking down at trembling pools of green algae.

[Image: The headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Image: The headwaters of the L.A. River].

We drove north to a suburb at the foot of the Cascades, its New Urbanist streets named after golfing legend Jack Nicklaus, its neighbors a surreal complex of municipal water-filtration ponds, DC-to-AC electrical conversion facilities, aqueducts, and warehouses, and we realized only after hiking far up above those mis-placed houses onto a hillside road and looking back down that the surrounding landscape was an abandoned golf course, with dead trees, clogged drains, and overgrown depressions that were once sand-traps, greens, and bunkers.

[Images: The Cascades, a dead tree, an abandoned golf course, a mirror].

[Images: The Cascades, a dead tree, an abandoned golf course, a mirror].

We walked the rim of the Hansen Dam, hiking down the side of that mind-boggling field of piled rubble.

[Image: Super-workshoppers descend the Hansen Dam].

[Image: Super-workshoppers descend the Hansen Dam].

Driving in a caravan through the obliterated landscapes of industrial San Fernando, we visited spreading fields for rubble and saw gravel conveyers at work, and then we headed further northeast into the debris basins of the San Gabriels. We got an introduction to the functional geometry of these mud-filled reservoirs with a site manager for the Army Corps of Engineers, who told us about a “geologic problem” up in the hills that he worries will fill all of L.A.’s basins any storm now, eyeing the mountaintops warily. We saw artificial hills of flattened dirt growing into a new state park with panoramic views of nearly the entire L.A. region, and we drove through whole neighborhoods lined with modular concrete deflection walls to protect the houses from future rockslides.

[Image: Debris basin at the top of Pine Cone Road].

[Image: Debris basin at the top of Pine Cone Road].

And then we headed back down into the city to walk along the L.A. River at sunset, underneath the 6th Street Bridge, unexpectedly overlapping with a crew filming CSI: NY, complete with fake NYPD cars driving by, as trains roared past the river and the concrete landscape turned orange, then purple, then black as evening arrived and we drove off for a final trip to see an oil-pumping site downtown, one where, decades ago, engineers over-pressurized the oil field causing black ooze to flow up and out through storm drains and collect inside neighborhood basements, as if Los Angeles had woken up some black, formless, Lovecraftian presence beneath the city.

[Images: The L.A. River at sunset].

[Images: The L.A. River at sunset].

And now, after more talks yesterday—about Owens Lake, regional water-supply systems, synthetic landscapes, and so on, after students had branched off to see local works by Frank Gehry, an active oil field in Culver City, and a church inside a converted bank (that used to be a film set)—we’re off to learn about robots in Pasadena. I’ll have more updates (and fewer pictures taken with Instagram) soon.

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery]. [Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Image: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Images: From Betel Nut Beauties by Magda Biernat, courtesy of Clic Gallery].

[Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: Gene Giacomelli and his lunar greenhouse; photo by Norma Jean Gargasz courtesy of

[Image: Gene Giacomelli and his lunar greenhouse; photo by Norma Jean Gargasz courtesy of

[Image: A glimpse inside the “oxygen garden” from Danny Boyle’s film

[Image: A glimpse inside the “oxygen garden” from Danny Boyle’s film

[Image: Like something out of the work of

[Image: Like something out of the work of  [Image: Landscape as if subject to the spatial kerning and leading of an agricultural typography; via

[Image: Landscape as if subject to the spatial kerning and leading of an agricultural typography; via

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

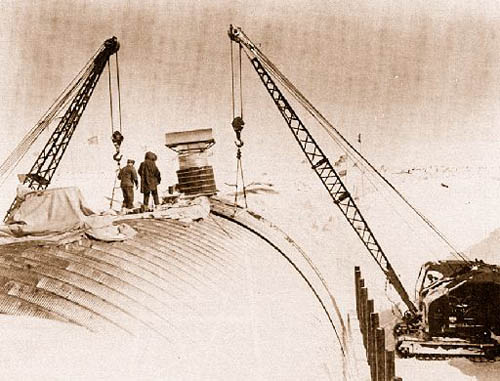

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

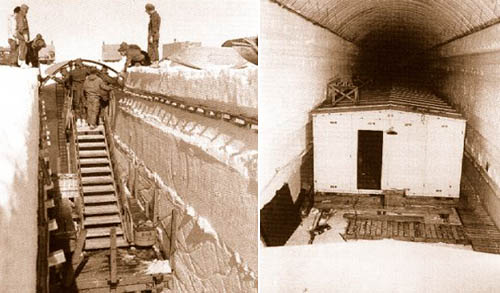

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

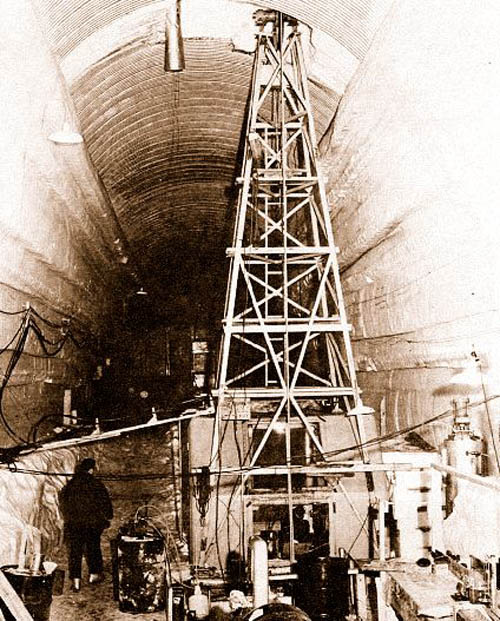

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

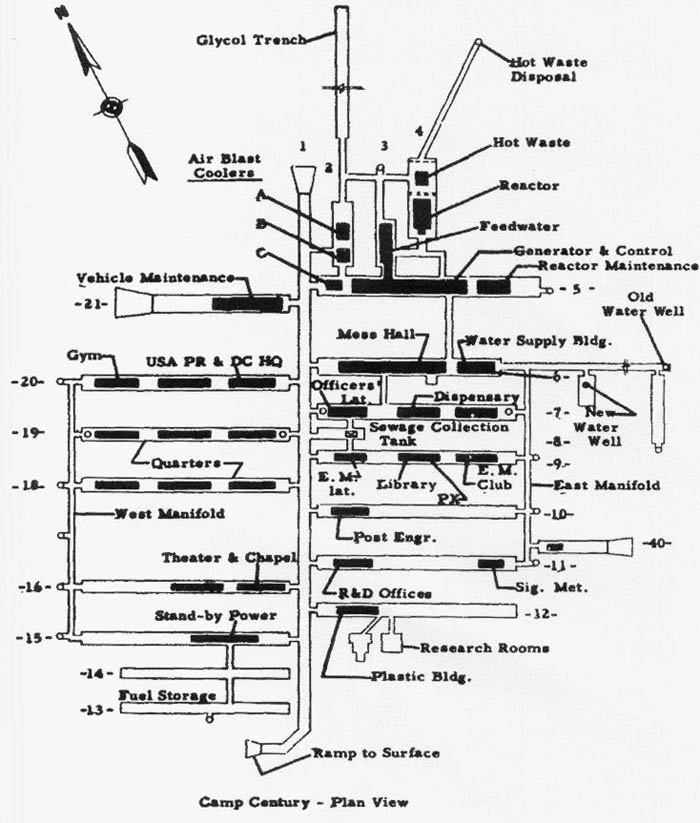

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via  [Image: The plan of Camp Century; via

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via  [Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

Specifically, the

Specifically, the

[Images: Illustrations by

[Images: Illustrations by

[Image: From a presentation by

[Image: From a presentation by

[Image: A bubbling tar seep near Wilshire Boulevard].

[Image: A bubbling tar seep near Wilshire Boulevard].

[Images: Skulls and bones at the La Brea Tar Pits].

[Images: Skulls and bones at the La Brea Tar Pits]. [Image: A “satellite tracking station” near the headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Image: A “satellite tracking station” near the headwaters of the L.A. River]. [Image: Learning about water infrastructure courtesy of the

[Image: Learning about water infrastructure courtesy of the  [Image: The headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Image: The headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Image: Super-workshoppers descend the Hansen Dam].

[Image: Super-workshoppers descend the Hansen Dam].  [Image: Debris basin at the top of Pine Cone Road].

[Image: Debris basin at the top of Pine Cone Road].

[Images: The L.A. River at sunset].

[Images: The L.A. River at sunset].