[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

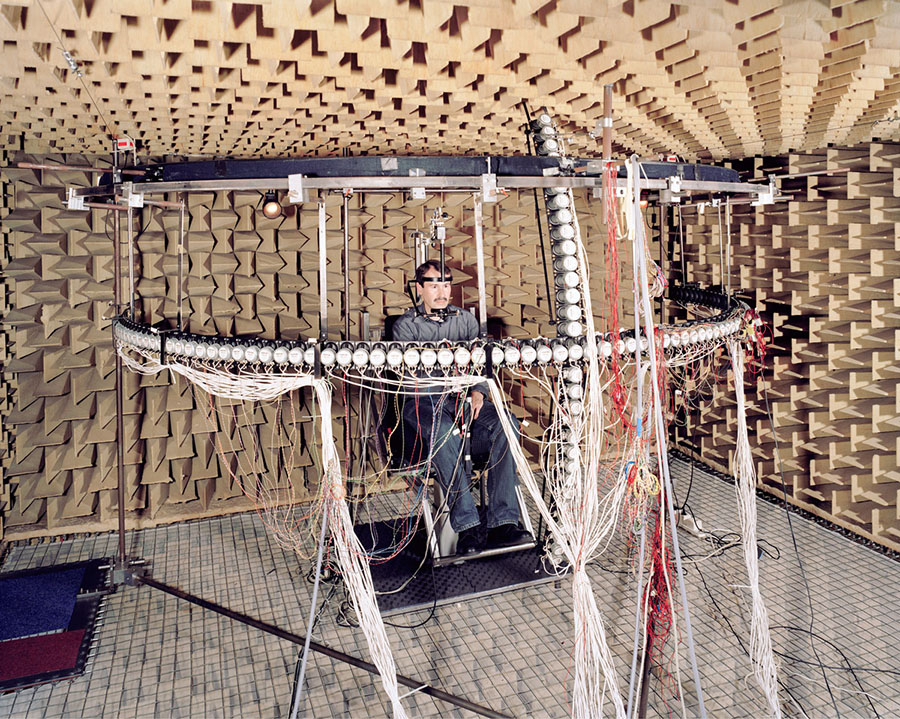

The 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing are something of a moonshot moment for artificial snow-making technology: the winter games will be held “in a place with no snow.” That’s right: “the 2022 Olympics will rely entirely on artificial snow.”

As a report released by the International Olympic Committee admits, “The Zhangjiakou and Yanqing Zones have minimal annual snowfall and for the Games would rely completely on artificial snow. There would be no opportunity to haul snow from higher elevations for contingency maintenance to the racecourses so a contingency plan would rely on stockpiled man-made snow.”

This gives new meaning to the word snowbank: a stock-piled reserve of artificial landscape effects, an archive of on-demand, readymade topography.

Beijing’s slogan for their Olympic bid? “Joyful Rendezvous upon Pure Ice and Snow.”

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

[Image: Snow-making equipment via Wikipedia].

Purely in terms of energy infrastructure and freshwater demand—most of the water will be pumped in from existing reservoirs—the 2022 winter games will seemingly be unparalleled in terms of their sheer unsustainability. Even the IOC sees this; from their report:

The Commission considers Beijing 2022 has underestimated the amount of water that would be needed for snowmaking for the Games but believes adequate water for Games needs could be supplied.

In addition, the Commission is of the opinion that Beijing 2022 has overestimated the ability to recapture water used for snowmaking. These factors should be carefully considered in determining the legacy plans for snow venues.

Knowing all this, then, why not be truly radical—why not host the winter games in Florida’s forthcoming “snowball fight arena,” part of “a $309 million resort near Kissimmee that would include 14-story ski and snowboard mountain, an indoor/outdoor skateboard park and a snowball fight arena”?

Why not host them in Manaus?

Interestingly, the IOC also raises the question of the Games’ aesthetics, warning that the venues might not really look like winter.

“Due to the lack of natural snow,” we read, “the ‘look’ of the venue may not be aesthetically pleasing either side of the ski run. However, assuming sufficient snow has been made or stockpiled and that the temperature remains cold, this should not impact the sport during the Games.”

Elsewhere: “There could be no snow outside of the racecourse, especially in Yanqing, impacting the visual perception of the snow sports setting.” This basically means that there will be lots of bare ground, rocks, and gravel lining the virginal white strips of these future ski runs.

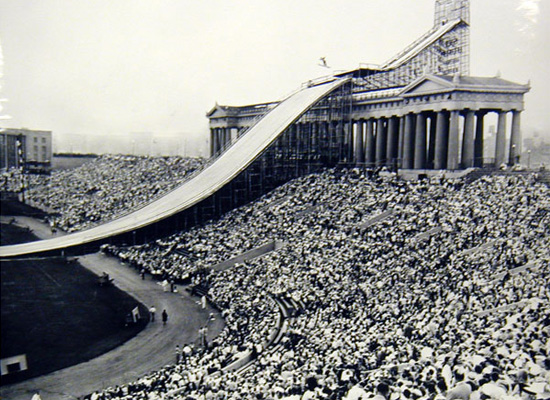

[Image: Ski jumping in summer at Chicago’s Soldier Field (1954); via Pruned].

[Image: Ski jumping in summer at Chicago’s Soldier Field (1954); via Pruned].

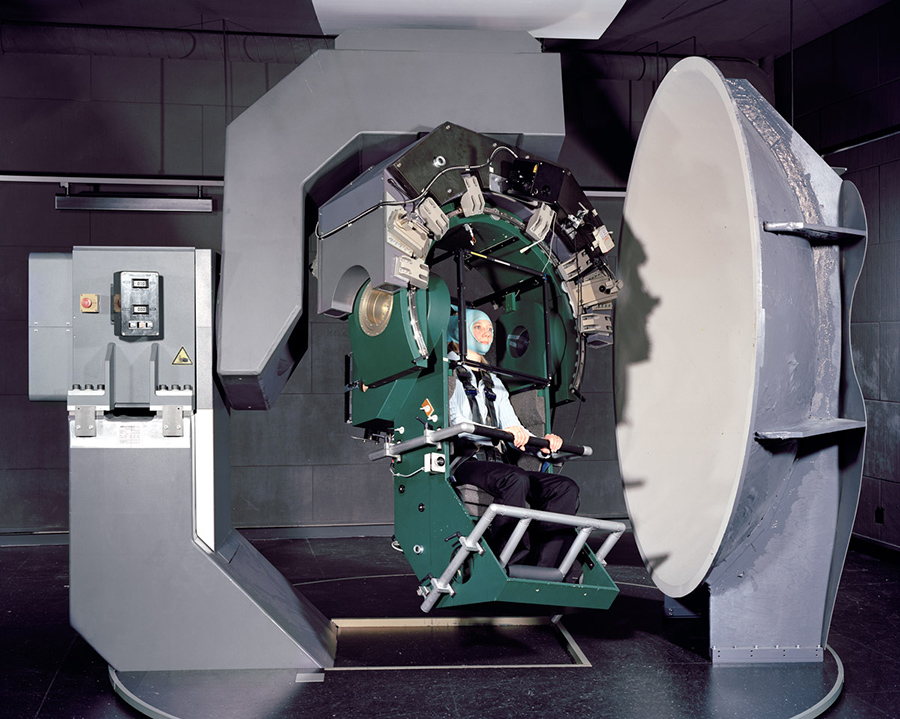

Several years ago, Pruned satirically offered Chicago as a venue for the world’s “first wholly urban Winter Olympics.” With admirable detail, he went into many of the specifics for how Chicago might pull it off, but he also points out the potential aesthetic disorientation presented by seeing winter sports in a non-idyllic landscape setting.

“Chicago’s gritty landscape shouldn’t be much of a handicap,” he suggests. Chicago might not “embody a certain sort of nature—rustic mountains, pastoral evergreen forests, a lonely goatherd, etc.,” but the embedded landscape technology of the Winter Games should have left behind that antiquated Romanticism long ago.

As Pruned asks, “have the more traditional Winter Olympic sites not been over the years transformed into high-tech event landscapes, carefully managed and augmented with artificial snow and heavy plows that sculpt the slopes to a pre-programmed set of topographical parameters?”

Seen this way, Beijing’s snowless winter games are just an unsustainable historical trajectory taken to its most obvious next step.

[Image: Making snow for It’s A Wonderful Life, via vintage everyday].

[Image: Making snow for It’s A Wonderful Life, via vintage everyday].

In any case, the 2022 Winter Olympics are shaping up to be something like an Apollo Program for fake snow, an industry that, over the next seven years, seems poised to experience a surge of innovation as the unveiling of this most artificial of Olympic landscapes approaches.

[Image: Illustration by

[Image: Illustration by  [Image: Hand-painted radiation sign at Chernobyl, via

[Image: Hand-painted radiation sign at Chernobyl, via

[Image: Horse skull via

[Image: Horse skull via  [Image: Inside the Paris

[Image: Inside the Paris

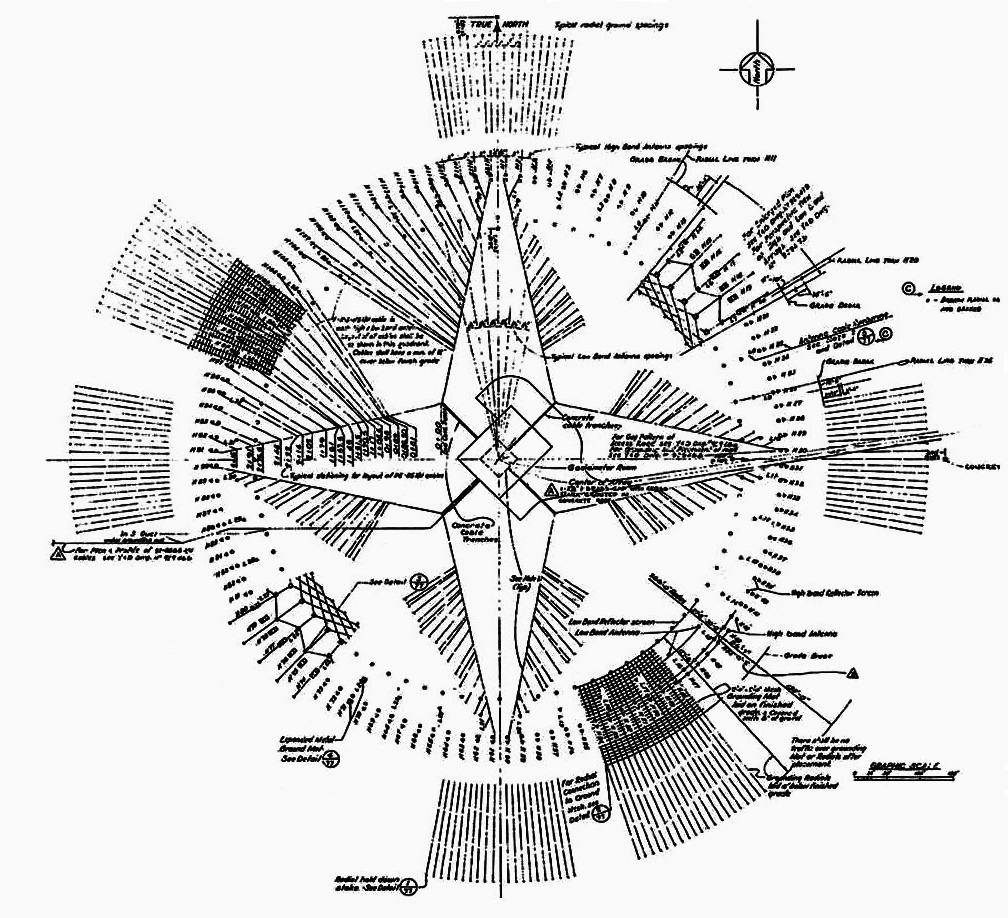

[Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the

[Image: Here’s another image from the same

[Image: Here’s another image from the same

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of  [Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of

[Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of

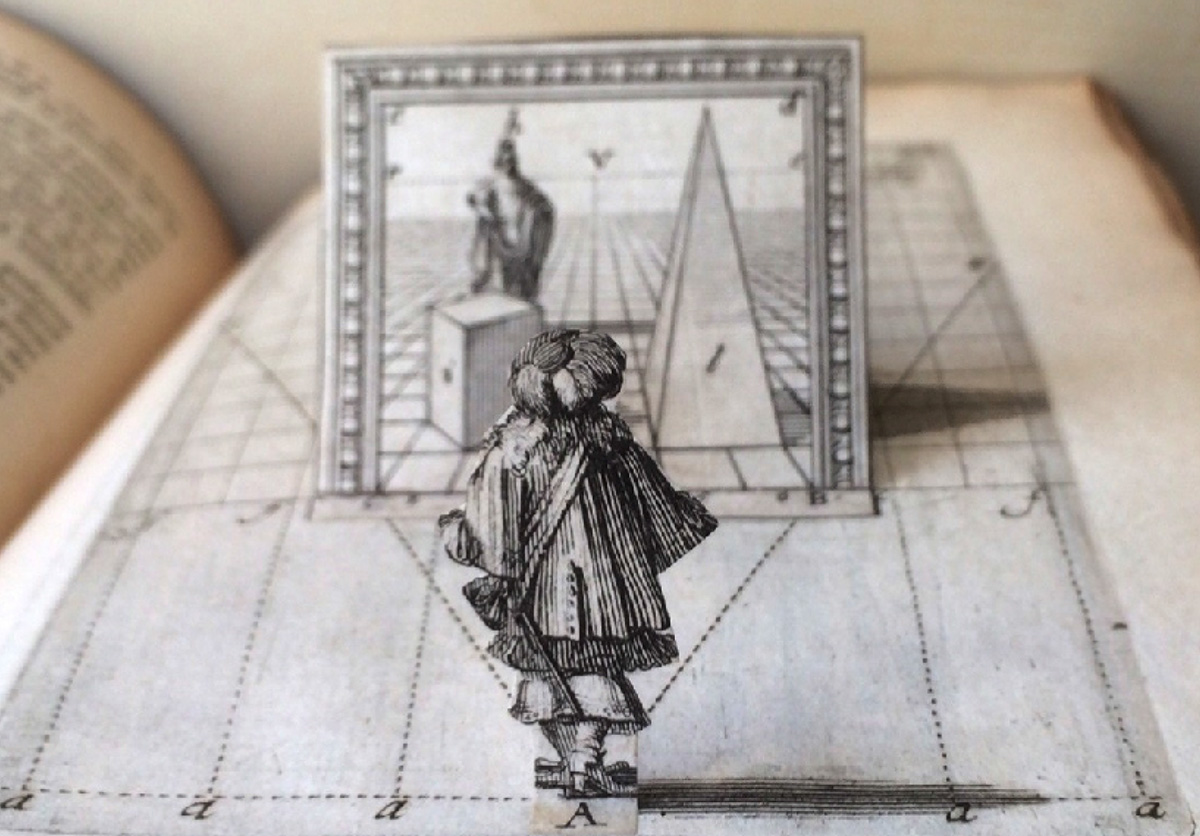

[Image: A figure and his optical context pop up from the pages of a 17th-century treatise on perspective by Abraham Bosse, defending the

[Image: A figure and his optical context pop up from the pages of a 17th-century treatise on perspective by Abraham Bosse, defending the

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image:

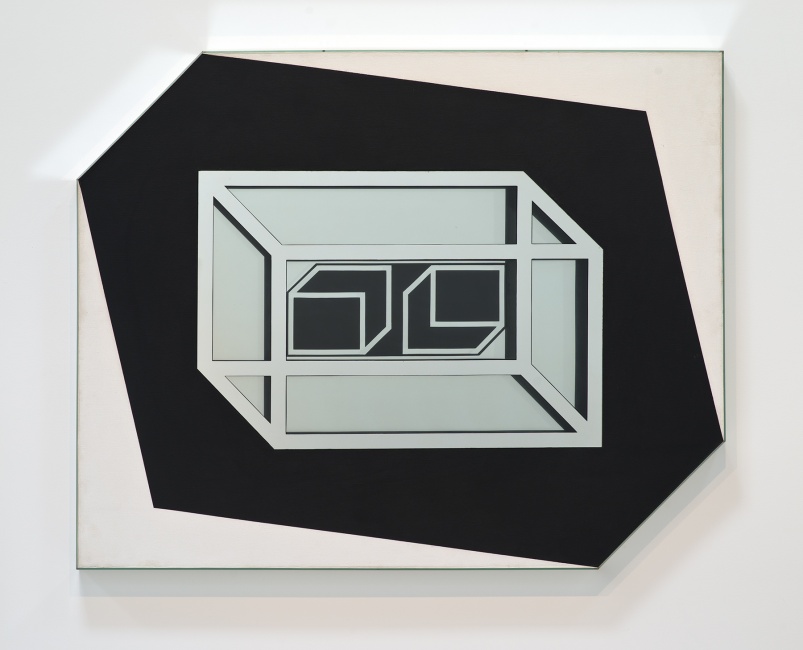

[Image:  [Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: A sidewalk corner in Los Angeles, albeit not the one for sale; via Google Street View].

[Image: A sidewalk corner in Los Angeles, albeit not the one for sale; via Google Street View].

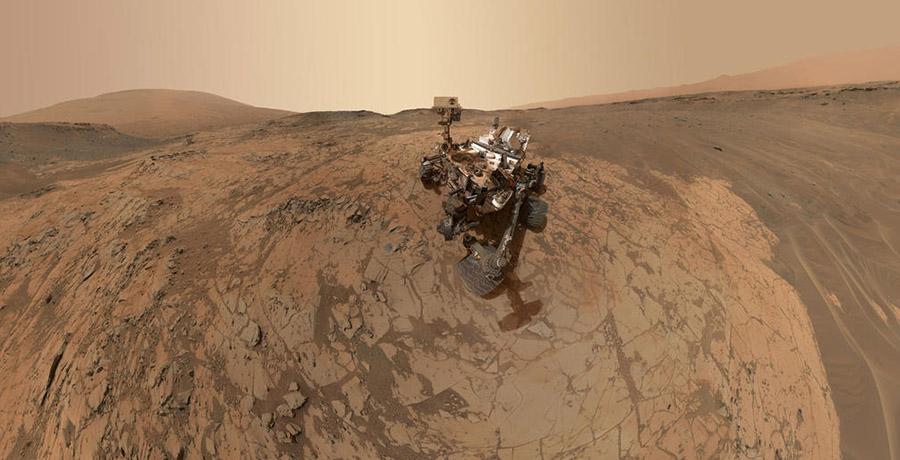

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via

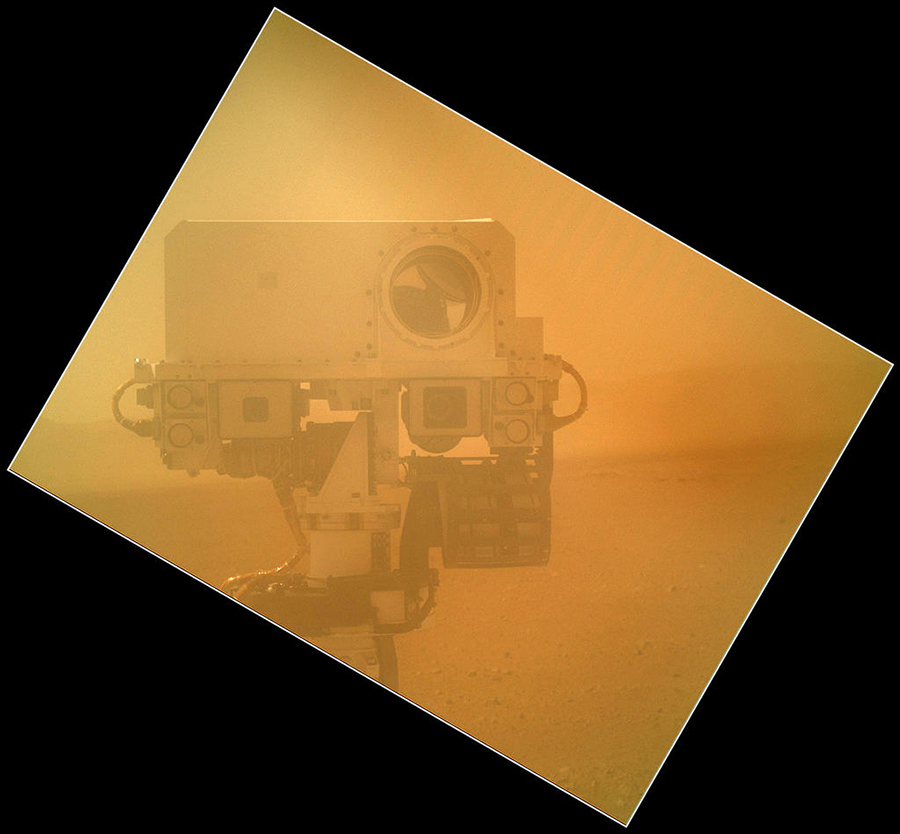

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via  [Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via

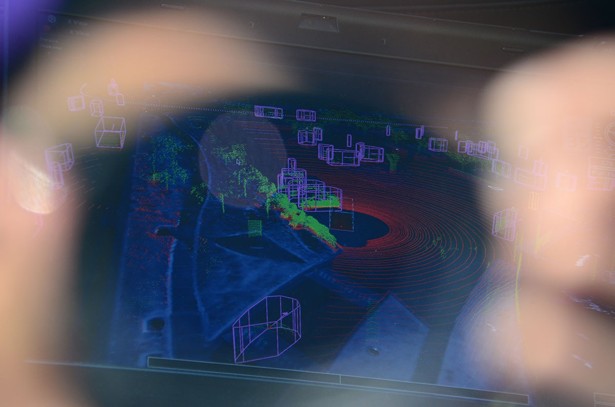

[Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via  [Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by

[Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from  [Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via

[Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via